CHAPTER VIII

TANGIER

TO see Morocco from another side—for we had looked upon the country so far only from behind French guns—we started up the coast on a little ‘Scorpion’ steamer, billed to stop at Rabat. But this unfriendly city is not to be approached every day in the year, even by so small a craft as ours, with its captain from Gibraltar knowing all the Moorish ports. A heavy sea, threatening to roll on against the shores for many days, decided the skipper to postpone his stop and to push on north to Tangier; and we, though sleeping on the open deck, agreed to the change of destination, for we had seen all too little of ‘the Eye of Morocco.’

Tangier is a city outside, so to speak, of this mediæval country. It seems like a show place left for the tourist, always persistent though satisfied with a glimpse. Men from within the country come out to this fair to trade, and others, while following still their ancient dress and customs, are content to reside here; yet it is no longer, they will tell you, truly Morocco. There is no mella where the Jews must keep themselves; Spaniards and outcasts from other Mediterranean countries have come to stay here permanently and may quarter where they please, and there is a great hotel by the water, with little houses in front where Christians, men and women, go to take off their strange headgear and some of their clothes, then to rush into the waves. Truly Tangier is defiled. Franciscan monks clang noisy bells, drowning the voice of the muezzin on the Grand Mosque; the hated telegraph runs into the city from under the sea; an infidel—a Frenchman, of them all—sits the day long in the custom-house and takes one-half the money; and no true Moslem may say anything to all of this.

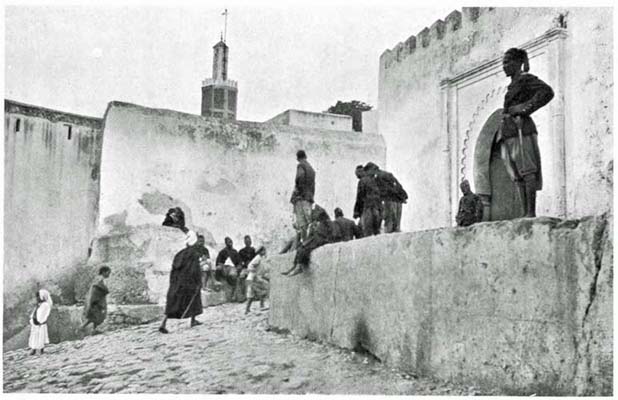

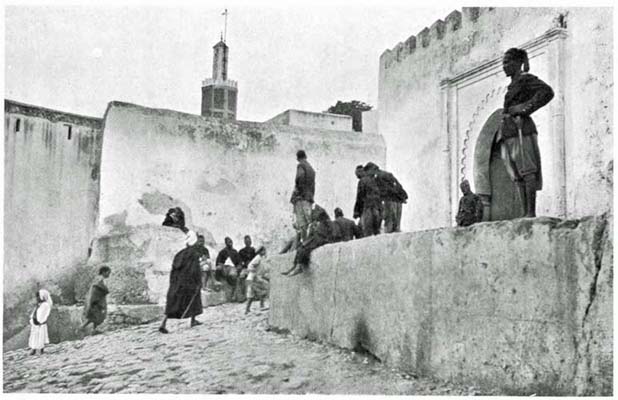

ON THE CITADEL. TANGIER.

Still there are compensations. The Christian may build big ships and guns that shoot straighter than do Moslem guns, but he is not so wise. He works all day like an animal, and when he gets much money he comes to Tangier with it, and true believers, who live in cool gardens and smoke hasheesh, make him pay five times for everything he buys. He is mad, the Nazarene.

Seated at a modern French or Spanish table at a café on the Soko Chico, the Christian is beset by youthful bootblacks and donkey drivers; and older Moors in better dress come up to tell in whispers of the charms of a Moorish dance—‘genuine Moroccan, a Moorish lady, a beautiful Moorish lady’—that can be seen at a quiet place for ten pesetas Spanish. One of them, confident of catching us, presents a testimonial; and with difficulty we reserve our smile at its contents:

‘Mohammed Ben Tarah, worthy descendant of the Prophet, is a first-class guide to shops which pay him a commission on what you buy. He will take you also to see a Moorish dance, thoroughly indecent, well imitated, for all I know, by a fat Jewish woman. He has an exaggerated idea of his superficial knowledge of the English language, and as a prevaricator of the truth he worthily upholds the reputation of his race.’ (Signed.)

The Soko Chico of Tangier, though an unwholesome place, is thoroughly interesting. About the width of the Strand and half the length of Downing Street—that is, in American, half a block long-it is large enough, as spaces go in Morocco, to be called a market and to be used as such. From early morn until midnight the ‘Little Sok’ is crowded with petty merchants, whose stock of edibles, brought on platters or in little handcarts, could be bought for a Spanish dollar. Mightily they shout their wares, five hundred ‘hawkers’ in a space of half as many feet. The noise is terrific. The cry of horsemen for passage, the brawl of endless arguments, the clatter of small coins in the hands of money-changers, and the strains of the band at the ‘Grand Café,’ struggling to make audible selections from an opera; all these together create an infernal din. The Soko Chico, where the post-offices of the Powers alternate with European cafés, is, of all Morocco, the place where East and West come into closest touch. The Arab woman, veiled, sits cross-legged in the centre of the road, selling to Moslems bread of semolina, and the foreign consul, seated at a café table, sips his glass of absinthe. Occasionally a horseman with long, bushed hair, goes by towards the kasbah, followed a moment later by the English colonel, who lives on the Marshan and wears a helmet. A score of tourists gather at the café tables in the afternoon, and as many couriers, with brown, knotty, big-veined legs, always bare, squat against the walls of the various foreign post-offices, resting till the last moment before beginning their long, perilous, all-night runs. Jews who dress in gaberdines listen to Jews in European clothes, telling them about America.

But there is another Sok, the Outer Sok, beyond the walls, where the camels and the story-tellers come, and this is no hybrid place, but ‘real Morocco,’ and as fine a Sok as any town but Fez or Marakesh can show. Here, across a great open space that rises gradually from the outer walls, are stretched rows upon rows of ragged tents as high as one’s shoulder, and before them sit their keepers: Arab barbers ready to shave a head from ear to ear or leave a tuft of hair; unveiled Berber women, generally tattooed, selling grapes and prickly pears, or as they call them, Christian figs; Soudanese, sometimes freemen, trading or holding ponies for hire; women from the Soudan, generally pock-marked and mostly slaves, squatting among their masters’ vegetables; Riff men who have come perhaps from forty miles away to sell a load of charcoal worth two francs; pretty little half-veiled girls, with one earring, selling bread broken into half and quarter loaves; soldiers feeling the weight of each small piece and asking for half a dozen seeds of pomegranate as an extra inducement to buy; minstrels and snake-charmers and bards; water-carriers tinkling bells; blind beggars with their doleful chants—‘Allah, Allah-la’; camel-drivers; saints. At dark the big Sok goes to bed with the camels and the donkeys and the sheep; man and beast bed down together; and it is an eerie place to pick one’s way through when the night is dark. From choice we lived, when in Tangier, across the big Sok, at the Hôtel Cavilla, and sometimes of an evening, after dinner, would descend the slope, passing through the gates, down the narrow, cobbled streets, to the Soko Chico, with its flaring cafés, to sit perhaps and watch a Moorish kaid pit his skill at chess against a German champion. It was the business of Kaid Driss, commander of artillery, to be in readiness at this central square to go to any gate which Raisuli or another hostile leader might suddenly attack; and so this splendid Moor, a well-liked gentleman, spent the weary hours until midnight at this, the Moors’ favourite game. Around the corners, under dank arches, slept his troops, covered even to their noses, their guns, too, underneath their white jelebas. Except the Kaid himself there seemed to be no other Moorish soldier stirring after nine, or at the latest, ten o’clock, and if we should delay our stay within the walls beyond this hour, nothing but a Spanish or other coin more valuable than a Moorish piece would quiet the complaining brave who pulled himself together to unbar the gates for us to pass.

It is not only, however, when the sun is down that the Moor sleeps; he sleeps by day, as he tells you his religion teaches, and rolled in woollen cloth lies anywhere that slumber overtakes him, in the sands upon the beach, on the roadway under gates—what difference does it make, the earth is sweet and a hard bed is best! Why work like the Christian to spend like a fool?

One day I saw a fisherman without a turban, sitting on a rock, beside him a sleeping bundle of homespun haik. They were a pretty pair, and with my kodak I proceeded out to where they were, going cautiously, intending to get a picture, from behind, of the shaved head and its single trailing scalp-lock. But the fisherman discovered me and hurriedly lifted the hood of his jeleba, muttering something. The sound waked the sleeping bundle, which moved itself a moment, then poked out a likewise shaven head and a youthful face thinly covered with sprouting beard. ‘You English man?’ said the head.

‘No, ’Merican,’ I replied.

‘Dat’s better; more richer. Open you mouth and show dis chap you got gold teeth.’

I did as he bade and disappointed him.

‘Me woman,’ he continued.

‘A bearded woman,’ I suggested; at which he laughed and explained (still lying on his back) that he had been to Earl’s Court once, in a show, that he had had no beard then, being but sixteen, and because he wore what seemed to Londoners to be a feminine attire they all thought he was a woman.

The Arab quarter of Tangier is entirely Moorish. The kasbah or citadel, high above the water of the Straits, has its own walls, as is customary, and within these, though the architecture may not be so fine as that at Fez, there is yet no Christian and no Christian way; it is thoroughly Moorish. The tourist may enter without a guide and poke his way through the heavy arches and the stair-like streets. He may go into the square where the Basha governing the district, like the Sultan at the capital, receives delegations and hears the messages of tribesmen in trouble; but the infidel, even though he be a foreign minister, may not enter mosque or fort or arsenal, or any other place except the residence of the kaid who is in command.

He may look in, however, at the door of the prison and even talk to victims crowded within, but there is much grumbling and no doubt some cursing if he goes away forgetting to distribute francs among the dozen jailers whose ‘graft’—to use an expressive American term—is to make a living in this way from Europeans. There is one man in prison here who speaks a little English and tells you that he has been in jail for more than ten long years and will be there for ever, for he has no money and his friends are far up country. He was imprisoned, so he says, because a rival told the Basha that he had smuggled arms from Spain. Now smuggling arms is a trade that meets, in ports where consuls do not interfere, with speedy execution. Not many years ago this punishment was meted out to some offenders even in Tangier. There is a graphic story of one such killing told in a book by an Italian, De Amicis, published many years ago:

‘An Englishman, Mr. Drummond Hay, coming out one morning at one of the gates of Tangier, saw a company of soldiers dragging along two prisoners with their arms bound to their sides. One was a mountain man from the Riff, formerly a gardener to a European resident at Tangier; the other, a young fellow, tall, and with an open and attractive countenance. The Englishman asked the officer in command what crime these two unfortunate men had committed.

‘“The Sultan,” was the answer—“may God prolong his life!—has ordered their heads to be cut off, because they have been engaged in contraband trade on the coast of the Riff with infidel Spaniards.”

‘“It is very severe punishment for such a fault,” observed the Englishman; “and if it is to serve as a warning and example to the inhabitants of Tangier, why are they not allowed to witness the execution?” (The gates of the city had been closed, and Mr. Drummond Hay had caused one to be opened for him by giving money to the guard.)

‘“Do not argue with me, Nazarene,” responded the officer; “I have received an order and must obey.”

‘The decapitation was to take place in the Hebrew slaughterhouse. A Moor of vulgar and hideous aspect was there awaiting the condemned. He had in his hand a small knife about six inches long. He was a stranger in the city, and had offered himself as executioner because the Mohammedan butchers of Tangier, who usually fill that office, had all taken refuge in a mosque.

‘An altercation now broke out between the soldiers and the executioner about the reward promised for the decapitation of the two poor creatures, who stood by and listened to the dispute over the blood-money. The executioner insisted, declaring that he had been promised twenty francs a head, and must have forty for the two. The officer at last agreed, but with a very ill grace. Then the butcher seized one of the condemned men, already half dead with terror, threw him on the ground, kneeled on his chest, and put the knife into his throat. The Englishman turned away his face. He heard the sounds of the violent struggle. The executioner cried out: “Give me another knife; mine does not cut!” Another knife was brought, and the head separated from the body. The soldiers cried in a faint voice: “God prolong the life of our lord and master!” but many of them were stupefied.

‘Then came the other victim, the handsome and amiable-looking young man. Again they wrangled over his blood. The officer, denying his promise, declared that he would give but twenty francs for both heads. The butcher was forced to yield. The condemned man asked that his hands might be unbound. Being loosed, he took his cloak and gave it to the soldier who had unbound him, saying: “Accept this; we shall meet in a better world.” He threw his turban to another, who had been looking at him with compassion; and stepping to the place where lay the bloody corpse of his companion, he said in a clear, firm voice: “There is no God but God, and Mohammed is His prophet!” Then, taking off his belt, he gave it to the executioner, saying: “Take it; but for the love of God cut my head off more quickly than you did my brother’s.” He stretched himself upon the earth, in the blood, and the executioner kneeled upon his chest....

‘A few minutes after, two bleeding heads were held up by the soldiers. Then the gates of the city were opened and there came forth a crowd of boys who pursued the executioner with stones for three miles, when he fell fainting to the ground covered with wounds. The next day it was known that he had been shot by a relation of one of the victims.... The authorities of Tangier apparently did not trouble themselves about the matter, since the assassin came back into the city and remained unmolested. After having been exposed three days the heads were sent to the Sultan, in order that his Imperial Majesty might recognise the promptitude with which his orders had been fulfilled.’

Since this incident of thirty years ago Tangier has changed. No longer may a man be flogged in public in the Sok; no longer may the slave be sold at auction; no longer may the heads of the Sultan’s enemies hang upon the gates; for the place is dominated now by foreign ministers. Though still in name within the empire of the Sultan, it is defiled for ever, gone over to the Christian.