CHAPTER IX

RAISULI PROTECTED BY GREAT BRITAIN

TWO years ago Tangier and the surrounding districts were governed by one Mulai Hamid ben Raisul, better known as Raisuli, a villainous blackguard who was finally deposed through the interference of the foreign legations. To-day this same Raisuli enjoys the interest on £15,000 (£5,000 having been given him in cash) and the protection ordinarily accorded to a British subject; and these favours are his because he deprived of liberty for seven months Kaid Sir Harry Maclean, a British subject in the employ of the Sultan Abdul Aziz. According to the terms of the ransom, which permit Raisuli, if he conducts himself in honourable fashion, to receive the sum invested for him at the end of three years, it is probable that the world will hear no more of him in his popular rôle; and, therefore, it might be interesting—also because of the light the story will throw on the ways of the Moorish Government and of diplomacy at Tangier—to sum up the exploits of this notorious brigand.

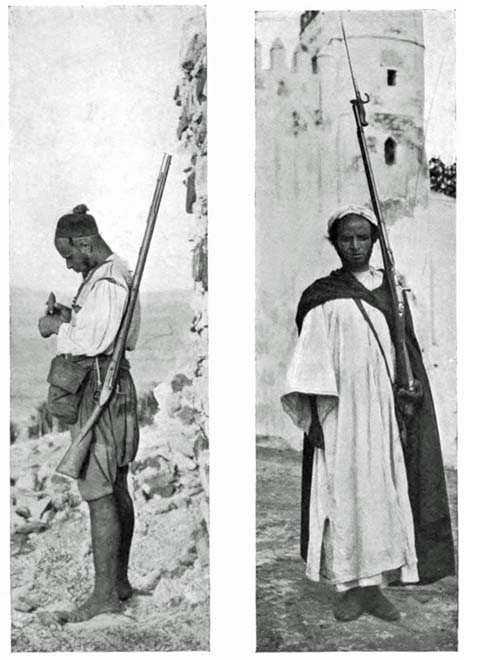

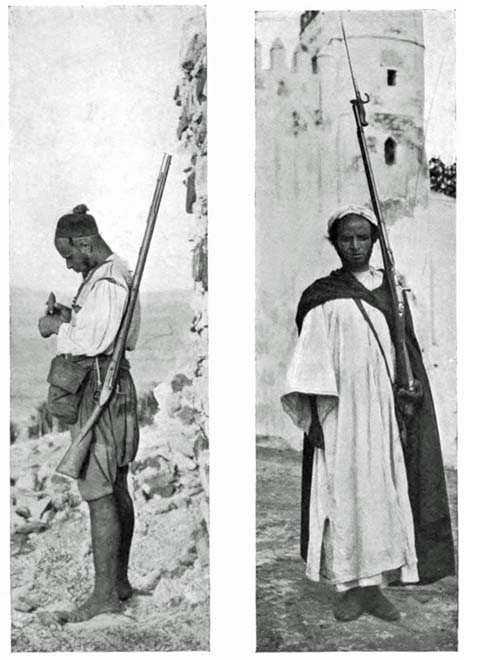

A RIFF TRIBESMAN. A MAGHZEN SOLDIER.

Raisuli, as his title Mulai implies, is a Shereef or descendant of the Prophet, and partly for that distinction, aside from personal power, he holds a certain influence over the K’mass and other tribes about Tangier. Being a shrewder villain than the others of his race who aspire to govern districts, he adopted early in his career other methods than that which is the custom—of purchasing positions from the Maghzen. The system of buying a governorship, to hold it only till some other Moor bought it over the head of the first and sent him to prison, did not appeal to Raisuli. The mountains of the Riff were impregnable against the feeble forces of the Sultan, and for a rifle and a little not-too-dangerous fighting all his tribesfolk could be got to serve him as their leader. So Raisuli started out for power—a thing the Moor loves—in a manner new to Morocco.

It was in 1903 that he captured his first European, the Times correspondent, W. B. Harris, who, speaking Arabic, negotiated his own surrender, and within three weeks left the mountains of the Riff on the release of a number of Raisuli’s men from Moorish prisons. For a year thereafter there prevailed intense fear in the suburbs, outside the walls of Tangier, where the better class of Europeans live. Raisuli had many followers, and the Maghzen was powerless against him, while raids about Tangier and robberies were of almost nightly occurrence. Yet some of the Europeans, those who felt a sentimental interest in the independence of Morocco and wanted to see the good old Moorish ways survive, seemed ready to welcome ‘the really strong man who was coming to the fore.’ It fell to the lot of an American of Greek descent, a Mr. Perdicaris, to receive the next pressing invitation to the interior. Raisuli and a band of followers entered the Perdicaris home one evening, and after breaking up many things, packing off others, and maltreating his wife, they escorted the American himself to their mountain fastnesses. As is the usual way of Western governments in these matters—I do not intend to suggest another method—the State Department at Washington demanded from the Sultan the release of the captive, pressing the demand with the visit of a warship. The Maghzen, seeing no other way, met Raisuli’s terms, again releasing many tribesmen, and paying the brigand £11,000, besides establishing him as governor of Tangier.

Of course in this capacity the ‘strong man’ superseded the European Legations in control of the town. The old order of things began to revive. Moors were beaten on the market-place; Moslems again insulted Europeans and jostled them in the streets; and soon, the Legations feared, heads would hang again upon the city gates. So an appeal went up to the Sultan that Raisuli be displaced, and Abdul Aziz, though he had evidently pledged himself to Raisuli, readily agreed to the demands of the European representatives. But the wary governor, getting wind of a plot, escaped to the mountains before the arrival of the Sultan’s emissaries; and though troops followed him, burned and pillaged his home and carried off his women, the fugitive himself escaped to renew armed hostilities against the Maghzen soldiers.

Unable to defeat the brigand at arms, after many months Abdul Aziz decided to employ diplomacy, and Kaid Maclean, old and wise in the ways of the Moors and trusted by those who knew him, undertook for the Sultan to convey new pledges to Raisuli and to guarantee them with the word of a Britisher. But the brigand wanted something more substantial, and though he had given his word of honour—his ïamen—that he would not molest the Kaid, the old Scotsman was made prisoner when he arrived; for Kaid Maclean went to meet Raisuli with only half-a-dozen men, hoping to inspire him with trust and to win his confidence.

After demanding, I am told, £120,000 (together with the release from prison of many tribesmen and the return of his women), the brigand finally agreed to accept the sum of £20,000 and the protection of a British subject. This last, which was proposed by the British Government, brings Raisuli of course under the jurisdiction of the Consular Court, and, to fetch him from the mountains in case he should be wanted, £15,000 of the £20,000 ransom is deposited to his credit in a bank, subject to his good behaviour. But I am not sure that the British Government did an all-wise thing. Foreign protection is greatly sought after by the Moors. In the case of others who enjoy it the power is used to plunder their fellows, and Raisuli may be expected to employ his strength and his new position in some cunning way. The Moorish authorities, always anxious to avoid encounters with the consulates and legations, generally allow protected subjects to do what they please. Raisuli may now exploit his fellow-countrymen with certain safety, or he may direct the profitable business of gun-running—at which he has already had considerable experience, like many other protégés and foreign residents—and no one is likely to protest.

At any rate it seems hardly fair to protect a villain in this manner.