CHAPTER XI

AT RABAT

AT the time that the Krupp Company were mounting heavy-calibre guns at Rabat other German contractors proposed to cut the bar of the Bu Regreg and open the port to foreign trade. But the people of both Rabat and Sali protested, saying that this would let in more Nasrani and that the half-dozen already there, who bought their rugs and sold them goods from Manchester and Hamburg, were quite enough. Up to the time the French gunboats appeared—preceded by the news of their effective work at Casablanca—the arrival of twenty Europeans at Rabat would have given rise to much murmuring and no doubt to a good many threats. Now, however, more than double that number of Frenchmen alone had come to the town. From Tangier had come the Minister of France and all his staff, accompanied by a score of soldiers and marines; and from Casablanca had followed a troop of correspondents, French and English. Yet the hapless Moors, stirred as they had never been before, were required to give them right of way.

‘Balak! Balak!’ went the cry of the Maghzen soldier, leading the Christians through the crowded, narrow streets, and meekly, usually without a protest, the natives stood aside. Most of the people did not understand. Had not the Prophet said that they should hate the Christians? Yet now their lord, Mulai Abdul Aziz, Slave of the Beloved, sat upon his terrace—so rumour vowed—sat with some Frenchmen and listened towards Ziada to the cannon of some other Frenchmen as they slaughtered faithful Moslems! At Rabat, besides the townsfolk, there were refugees from Casablanca; there were tribesmen still in arms; there were saints who had followed the Sultan from Fez; there were madmen who are sacred, and impostors who pretended to be mad; there were soldiers trained to every crime; in short, there were men from every corner of the variegated empire, any one of whom would gladly have laid down his life to slay a Christian had the Sultan so commanded. Yet months have passed and they have kept the peace, though Frenchmen still slay Moors within the sound of Rabat’s walls.

A Shawia tribesman who spoke a little English, a tall young man with dark skin, and an ear torn by an earring at the lobe, met us at the landing and extended his hand. He took upon himself to help us with our luggage, and we let him show us the way to the French hotel lately opened. Of course this man was anxious to serve us as guide and interpreter, and we were glad to have him. Driss Wult el Kaid was his name, Driss, son of the Kaid. He had worked for Englishmen at Casablanca, and from his accent we could tell they had been ‘gentlemen.’ No ‘h’s’ did he shift from place to place, while his pronunciation of such words as ‘here’ and ‘there’ were always drawled out ‘hyar’ and ‘thar.’ ‘Now, now,’ he would say with a twisting inflection, for all the world like an Oxford man wishing to express the ordinary negative ‘no.’ It was humorous. English of this sort, to the mind of a mere American, associates itself with aristocracy, while the face of a mulatto goes only with the under-race of the States. It was difficult, in consequence, to reconcile the two. But Driss soon demonstrated that he was worthy to speak the language of the upper man. The manners and the dignity of a ruling race were his heritage; and proud he was, though his bearing towards the poorest beggar never appeared condescending. A gentleman was Driss. ‘Me fader,’ he told us in fantastic Moro-English, ‘me fader he was one-time gov’nor Ziada.’

‘Is he dead?’

‘Now, now; he in prison.’

‘What for?’ we asked.

‘Me fader,’ Driss explained, looking sorrowful, ‘he paid ten thousan’ dollar Hassani for (to be) gov’nor; two year more late ’nother man pay ten thousan’ dollar more, and he ’come gov’nor; me fader got no more money, so go prison.’ This was the old story, the same wherever Mohammedans govern; one man buys the right to rule and rob a province; over his head another buys it, to be succeeded by a third, and so on.

We told Driss that this could not happen if the French ruled the country; it could not happen, we said, in Algeria.

‘I know, I know,’ said Driss. ‘Me fader he write (wrote) in a book about Algeria, and he teach me to read. Tell me, Mr. Moore, is it true a man can give his money to ’nother man and get a piece of paper, then go back long time after and get his money back?’

I told Driss that there were such institutions as banks, which even the Sultan could not rob; and he believed, but seemed to wonder all the more what manner of men Christians were. ‘It is fiendish; no wonder they defeat us; they work together inhumanly,’ he seemed to say; ‘indeed you cannot know our God!’

Good old Driss; both Weare and I became very fond of him. In a day he spoke of himself as our friend, and I believe we could have trusted him in hard emergencies. He was brave and not unduly cautious, though occasionally, when we would stop in a road and gather a crowd, he would say imperatively: ‘Come away, Mr. Weare and Mr. Moore; some fanatic may be in that crowd and stick you with his dagger. Come on, come on!—I’m your friend; I don’t want see you dead.’

Driss had vanities. He told us his age, twenty-three, and told us in the same breath that few Moors knew exactly how old they were. He said his wife—who was only twenty—could read and write a little, informing us at the same time that very few women could read. He told us that his wife was almost white. Driss was ashamed of his own colour, and when a French correspondent asked in his presence if he was a slave, the poor boy coloured and dropped his head. He had certainly been born of a slave.

Still there was nothing humble about Driss. Among his people he was exceptional and he enjoyed the distinction. He was a Ziada man; he could read and write; he could make more money than his fellows—and he hoped some day to acquire European protection; he was fine-looking, tall, strong, and without disease.

Driss was a thoroughly clean fellow. He never touched bread without washing his hands, a custom prevailing among some Moslems but not general with the Moors. This with him seemed only a matter of habit and desire of decency, for he was not particularly devout in his religion.

‘But you think,’ we said, ‘that all Nasrani are unclean.’ At first Driss denied this, out of consideration for us, but on being pressed he admitted that it was the feeling of the ignorant of his race that, like pigs, all Christians were filthy in person as well as soul.

We discussed with him the great moral vice of Mohammedan countries, and he admitted that it was prevalent in Morocco no less than, as we told him, it prevailed farther east, and that it affected all classes. He told me that it was the custom of the wealthy father of the better class of Moors, in order to protect his sons, to make them each a present of a slave girl as they attain the age of fifteen or sixteen. Of course, from the Mohammedan point of view, there is nothing immoral in this; indeed the mothers of sons often advocate it.

It was the fasting month of Ramadan at the time of our sojourn at Rabat, and no one could eat except at night. Every evening at six o’clock a white-cloaked gunner came out of the Kasbah walls and rammed into his antique cannon a load of powder sufficient, it would seem, to raise the dead of the cemetery in which it was discharged. For two reasons—that it was the cemetery and that the Ramadan gun was here—this was the gathering-place of all Moslems. Often we, too, went up to see the crowd and to watch with the gunner and the other Moors for the signal. All eyes were turned, not towards the Atlantic to see old Sol set, but inland, towards the town, where towered above the low houses a great white minaret, whence the Muezzin watched the sun and signalled with a banner of white. At the blast of the cannon a great shout went up from the hundred small boys gathered about; and, with the slope of the hill to lend them speed, everybody went hurrying into the town, the skirts of those who ran fluttering a yard behind them. In a minute came the boom from the gun of the m’halla, the city of tents, on the hills visible beyond the town walls. When we passed down the streets to our supper five minutes later, everybody was swallowing great gulps of hererah, Ramadan soup, breaking the long day’s fast. The little cafés, dingy and deserted during the day, were now brilliant and crowded, the keeper himself eating with one hand while he served with the other; and the roadway was studded with little groups of men who had squatted where they stood half-an-hour before the setting of the sun, and, spoon in hand, waited for the gun to boom.

Christians and Mohammedans treat their religions with a curious difference: where the one is generally ashamed of reverence and never flaunts his faith, the other is afraid not to make a considerable show of his. Not a Moor would dare to eat or even touch a drop of water in the sight of another during Ramadan; though under our window overlooking the river it was the custom of an old beggar to come daily at noon, to roll himself into a ball on the ground as if sleeping, and under the cover of his ragged jeleba make his lunch. Had he been caught at this he would probably have been stoned out of town.

One day during Ramadan we were taken by a Jewish merchant, a British subject, to the house of a wealthy Moor with whom he traded in goods from Manchester. The house was down a turning off the street of arches, and the turning came to an end at the Moor’s door, a massive oaken door with the heads of huge rivets showing every six or seven inches. It was the width of the narrow street, about six feet, and the height of one’s shoulder. We approached quietly and knocked lightly, for our friend told us that the Moor did not care for his neighbours to see us entering his house. The entrance, which was at one corner of the square house, led into the courtyard, of which the ornate walls were spotlessly white-washed, the floor was of green tiles, and the roof, as is usual, of glass. The reception room, the length of one side of the house, though but twelve feet wide, had low divans all round the walls, leaving but a long, narrow aisle the length of the room, to the right and to the left of the arched entrance. Rising in tiers at each end were broader divans, to appear as beds one beyond another, though their luxurious and expensive upholstering, covered with the richest of native silks, were evidently never displaced by use. About the room, in cases above the divans, were many little ornaments, noticeably tall silver sprinklers filled with rose-water and other perfumes; but most curious to us were the innumerable clocks, most of them cheap things, all set at different hours in order that their bells should not drown each other’s melodious clangs.

Two little slave girls, who giggled at us all the while, brought in a samovar much after the Russian pattern, and silver boxes of broken cone sugar and of European biscuits. Our host made tea in the native fashion, brewed with quantities of sugar and flavoured heavily with mint; green tea, of course. He filled our cups again and again, though he would take nothing, till we too wished we respected Ramadan, for we were told by our Jewish friend that it would be impolite to drink less than five or six cups. Along with this refreshment the silver sprinklers were passed us by the giggling little blacks, that we might sprinkle our clothes, and no doubt they thought we needed perfuming, though they did not hold their noses, as other Europeans have told me they often do when close to Nazarenes. Perhaps their master had instructed them in good behaviour, for he was indeed a gentleman, and he had travelled on one occasion to London and to Paris. It was at this point, when the Moor, with immaculate fingers, sprinkled his own long white robes, that one could appreciate their feeling that we are filthy people. We wear the same outer garments for months, and they are never washed; indeed, we wear dark colours that the dirt may not show; here we had entered upon this gentleman’s precious carpets with our muddy boots, where a sockless Moor would shift his slippers. And they have habits too which make for bodily cleanliness, habits which they know we have not, as, for instance, that of shaving the hair from every part of the body but the face. Our conversation was chiefly on comparisons of customs, our host noticing that we shaved our faces, the Moors their heads, and we remarking—for he was too polite—that we kept on our shoes when we entered a house, whereas the Moors wore their fezzes or their turbans. He said that he had beheld in London the extraordinary sight of a pair of ordinary Moorish slippers set upon a table as an ornament; and he had seen also the woman sultan, Queen Victoria.

At Ramadan there are generally continual street festivities during the eating hours of the night; but the gloom cast over the country by the presence of the French kept these now to a minimum. There was not even, in spite of the Sultan’s presence any powder play, a thing which I was particularly anxious to witness, to learn for myself to what degree the Moors are hard upon their animals. I know that Moslems are seldom deliberately cruel; but I know, too, that the vanity of the Moor makes him ride with a cruel bit and a pointed spur that could reach the vitals of a horse, and both of these, I have heard, they employ in a vicious manner in their famous, dashing powder play. But most of their cruelty is only from neglect, laziness, and ignorance. Camels wear their shoulders and their necks through to the bone—the sight is a common one—because their masters do not trouble to pad their packs properly; two men will ride an undersized donkey already overloaded with a pack; and, as is the way among all Moslems, an animal when it comes to die may suffer for weeks or months, yet will not be killed because ‘Allah gave life, and Allah alone may take it away.’ Still there is the Moorish sect of Aisawa, that in a mad stampede tears a sheep to pieces in the streets and eats it still palpitating.

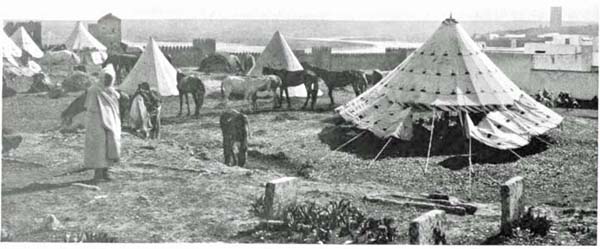

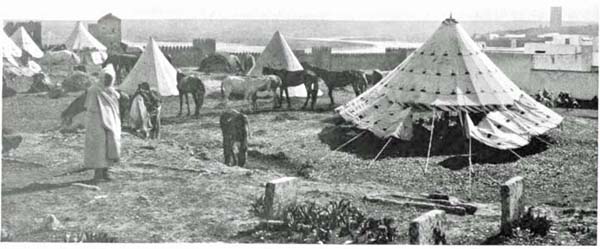

A CAMP OUTSIDE THE WALLS OF RABAT.

There were some interesting Englishmen at Rabat, notably the Times correspondent, W. B. Harris, who has travelled with several Sultans of Morocco, and lived some time as a Moor in order that he might learn their ways and penetrate to the farthest reaches of the country forbidden to the Christian. There was also Mr. Allan Maclean, likewise an authority on Morocco, now busy with the Maghzen to arrange for the release of certain prisoners, which Raisuli exacted as one of the stipulations of Kaid Maclean’s release. There was then the British Consul, George Neroutsos, an old friend of the Sultan and a man whom he often consults on matters of European policy.

With some of the Englishmen we took long rides around the town, passing several times through the m’halla, where we were never welcome; the camp of Abdul Aziz was in sympathy with Mulai Hafid. We saw the soldiers who were sent to fight Hafid and joined his ranks with all their arms. Gradually we saw the army dwindle away until there could have been no more than four thousand men between the discredited Sultan and his hostile brother, whose following of tribesmen was reported to number variously from twenty to sixty thousand men. Had the army of the French not stood between them and fought the Hafid m’hallas, Rabat would surely have fallen and Abdul Aziz would now be a royal prisoner safe in the keeping of his brother. For want of money to pay the troops Abdul Aziz was forced to pawn his jewels; and at last, by a royal decree, he made good ‘a hundred sacks’ of silver coins that had been confiscated as counterfeit. It was because of a threatened revolt of the troops for want of pay that the Spaniards in February occupied the port of Mar Chica.