CHAPTER X

DOWN THE COAST

LUCK with me seems to run in spells. Once on a campaign in the Balkans I had the good fortune to be on hand at everything; massacre, assassination, nor dynamite attack could escape me; I was always on the spot or just at a safe distance off. In Morocco things went consistently the other way. Beginning with the Casablanca affair when I was in America, everything of a newspaper value happened while I was somewhere else. The day the Sultan entered Rabat after his long march from the interior, I sailed past the town unable to land. Now I was to be taken to Laraiche, when a month before I had failed to get there to meet the two score European refugees coming down from Fez.

We took passage—Weare and I—on the same little steamer by which we had come to Tangier, bound now down the Atlantic coast, again intending to stop at Rabat, ‘weather permitting.’ There was not a breath of air; the sea was ‘like a painted ocean’; every prospect favoured. But our captain, the Scorpion villain, hugged the coast with a purpose, and as might have been expected the ship was signalled at Laraiche. We had to stop and pick up freight, which proved to be some forty crates of eggs billed for England. Old memories of unhappy breakfasts revived, and, our sympathies going out to fellow Christians back in London, we argued with the captain that it was not fair to take aboard these perishable edibles till he should return from Mogador. But the captain smiled, putting a stubby finger to his twisted nose, and explained that though eggs were eggs, the wind might be blowing from the west when the ship passed back. But though my ill-fortune in Morocco was enough to ruin the reputation of a Bennet Burleigh, there were always compensations, and on this occasion we were recompensed with a sight of the most fascinating port along the Moorish coast.

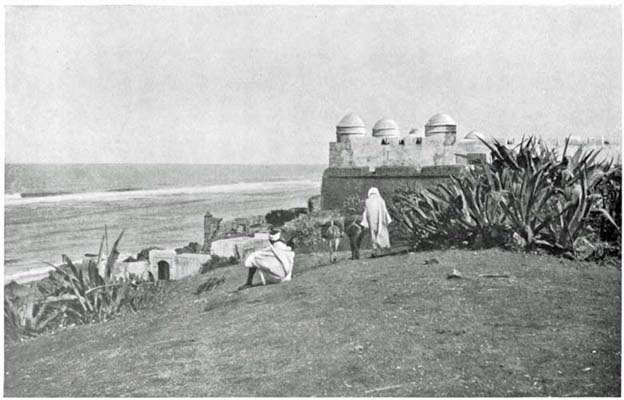

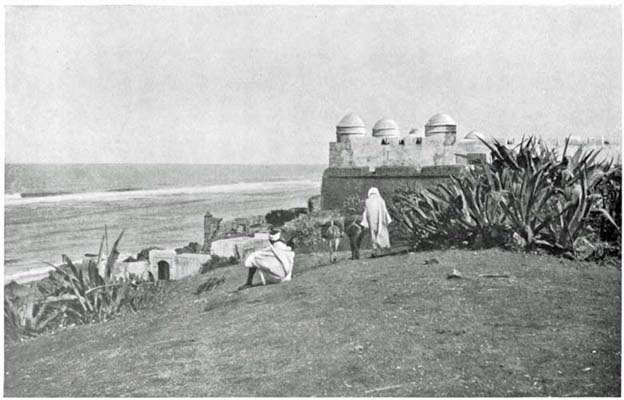

As the ship moves into the river cautiously, to avoid the bar, you ride beneath the walls and many domes of a great white castle, silent, to all appearances deserted, and overgrown with cactus bushes. Below—for the castle stands high upon a rock—is an ancient fortress, also white, which the ship passes so close that it is possible, even in the twilight, to make out upon the muzzles of the one-time Spanish guns designs of snakes and wreaths of flowers; and looking over the parapet you may see the old-time mortars made in shapes like squatting gnomes. From the ship that night we watched the moon rise and the phosphorescence play upon the water, and the splendid Oriental castle took on a fairy-like enchantment.

THE CASTLE AT LARAICHE.

In the morning the little city appeared unlike other Moorish towns; where they are mostly grey or white, with here and there a green-tiled mosque, Laraiche affects all manner of colour. Among the white and blue houses there may be green or orange, yellow or brown or red, and likewise the inhabitants, curiously, go in for gaily coloured cloaks. On one side of the river this brilliant city rose from the ancient walls; on the other a cluster of sand dunes sloped back to the hills a mile or more away, and behind them, far in the distance, towered the Red Mountain, which Raisuli has made famous. Great lighters, things like Noah’s arks, rowed by fifteen, sometimes twenty, turbaned men, pushed off from the little quay to bring our cargo, and smaller craft began to cross the river to ferry over country people and their animals, along with one or two poor, fagged-out letter carriers, who had come afoot from Tangier, forty miles, overnight. By one of the smaller boats which came alongside we went ashore, to remain three days awaiting a further belated shipment of grain that came by camel train from the interior. We went to the only hotel, kept of course by a Spaniard, though designed specially to attract the British tourists of the Forwood line. The walls of the tiny, wood-partitioned rooms (spacious Moorish halls cut to cubicles) are papered like children’s playrooms, with pictures from old Graphics and other London weeklies, planned no doubt to amuse the visitor when it rains, for on such occasions the streets of Laraiche are veritable rapids. The room which I occupied hung over the city walls and looked down on the banks of the river, dry at low tide. Being waked early one morning by some hideous sounds and muffled voices, we peered cautiously out of the window and in the dim light discerned a crowd of black-gowned Jews not twenty feet below, killing a cow. This bank at low tide is the slaughterhouse, where a dead beast of some kind lay continually. Fortunately the rising waters carried off the few remains that Jews and Moslems left; and fortunately, too, the place was not used also as the boneyard, where animals that have died of natural causes are dragged and heaped uncovered. Such a spot there is outside the walls of every Moorish town.

Laraiche is off the great trade routes, and the district round about is unproductive. For these reasons its poor inhabitants, unable to own guns and riding horses, are peaceable and submissive. The town as well as the surrounding country is safe for any Christian, and even insults for him are few. We went with our ragged old guide, who bore the fitting name of Sidi Mohammed, up through the Kasbah, as fine a ruin of Moorish architecture as I have seen, and out through a long tunnel to the quaint old market-place, broad and white, flanked on each side by long, low rows of colonnades, the ends, through which the trains of camels come, sustained by several arches, none the same, opening in various directions. Certainly the Moors who built this town were architects and artists too. But the poverty and the degradation of the place! The houses, dark and wretched; the tea-shops foul and small and crowded much like opium dens; the people lean and miserable and cramped with hungry stomachs, dirty and diseased. Though clad in rags of brightest colours, the average human being is marked over with pox or something worse, and his head is scaly, the hair growing only in blotches. Children follow you, with paper patches, the prayers of some mad saint, tied about their running, bloodshot eyes; old men hobble by, one lean leg covered with sores, the other swollen huge with elephantiasis, both bare and horrible. Laraiche is beautiful and awful.

We saw a funeral here, and I thought we Christians could learn something from these Moors. In this sad country a man is hardly dead before they bury him. As soon as the grave can be dug the corpse is taken on the shoulders of friends, and quickly, to the music of a weird chant, borne to the grave. Without a flood of agony and an aftermath of long-extended mourning, the body is consigned to earth, and the soul that has departed, to the tender mercy of almighty God. An unmarked sandstone is erected; and if a relative wore a cloak of green or red before the parting, green or red is his colour still.

The day we left Laraiche a heavy breeze blew from the sea, white-capped rollers broke upon the shore, and we knew that Rabat was not to be reached. We passed on to Casablanca, where, the harbour being better, we were able to land. Now after all these disappointments we were resolved to get to Rabat at any cost. If it were necessary, we would go by land and run the gauntlet of the Shawia tribes, professing to be Germans deserting from the Foreign Legion; but the French consul saved us this. From him we obtained permission to go back by torpedo-boat and to be transhipped, so to speak, to the cruiser Gueydon, where we might stay as long as was necessary, as the ship was permanently anchored off Rabat. In two days after boarding the Gueydon the Atlantic calmed, and we left, bidding adieu to our French hosts, to cross the bar of the Bu Regreg in a twenty-oared Moorish boat.