CHAPTER XIII

MANY WIVES

WE were up on the Kasbah, the high rocky citadel that rises nearly two hundred feet straight above the notorious bar of the Bu Regreg, taking in a splendid view of the river’s winding course together with the city of Salli. When a caravan of unusual size twisted out of Salli’s double gate and came across the sands to the water’s edge, where a score of ferry boats nosed the bank, their owners began jumping about like madmen, frantic for the promised trade that could not escape them. On market days at Rabat there are always camel trains and pack trains of mules and horses crossing these sands of Salli to and from the barges that ferry them over the river for a farthing a man and two farthings a camel, but they seldom come in trains of more than twenty. This winding white company, detached in groups of sometimes four, sometimes forty, stretched from the wall to the water’s edge, a distance of half a mile; it spread out on the shore, and still kept coming from the gate. Neither Weare nor I had heard that the Sultan’s harem would arrive this day, and we had to reproach our faithful Driss Wult el Kaid, to whom we had given standing orders to move round among his countrymen and let us know when things of interest were happening.

‘Plenty time, Mr. Moore,’ said Driss, holding up his brown hands and chuckling. ‘There are many, many; more ’an three hundred, and many soldiers, and many Soudanese,’ by which last Driss meant slaves. There was indeed plenty of time; it took the company all that day and part of the next to cross by the slow, heavy barges, carrying twenty people and half-a-dozen animals at each load, and rowed generally by two men, sometimes by only one.

We descended from the Kasbah and made our way down the street of shops, the Sok or market street, as it is called, and out through the Water Port to the rock-studded sands upon which the caravan was landing. It was an extraordinary sight. The tide was out, and the water, which at high tide laps the greenish walls, now left a sloping shore of twenty yards. The boats when loaded would push up the river close to the other shore, then taking the current off a prominent point, swing over in an arc to the Rabat side. Empty, they would go back the same way by an inner arc. On our side they ran aground generally between two rocks, when the black, bare-legged eunuchs, dropping their slippers, would elevate their skirts by taking up a reef at the belts, and jump into the water to take the women to dry land on their stalwart backs. Only in rare instances did much of the woman’s face show—and then she was a pretty woman and young; those old or pock-marked were always careful to cover, even to the extent of hiding one eye. Nevertheless the wives of the Sultan as they got upon the backs of his slaves gathered their sulhams up about their knees, displaying part of a leg, in almost every case unstockinged, and always dangling a heelless slipper of red native leather. In Morocco, as I have indicated before, the costumes of men and those of women are practically the same except for fullness and, in the case of nether-garments, colour. The short trousers of a man, for instance, are generally brown and his slippers never anything (when new) but yellow.

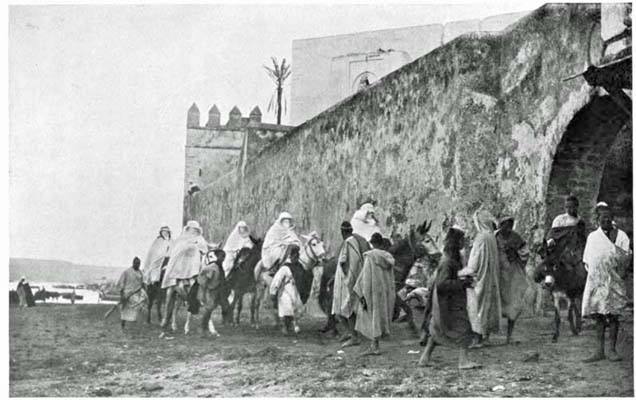

The Sultan’s wives with few exceptions were covered in white sulhams; round their heads were bands of blue ribbon knotted at the back, fixing their hoods and veils for riding. While the slaves brought up the luggage, working with a will like men conducting their own business, the women held the mules and horses, covered with wads of blanket, all of Ottoman red, and mounted with high red Arab saddles. The women were usually subdued and to all appearances modest, though all of them would let their black eyes look upon the infidels longer than would the modest maid of a race that goes unveiled. But of course we were a sight to them not of every day. Now and then a lady whose robe was of better quality than most, seemed distressed about some jewel case or special piece of luggage, and worried her servant, who argued back in a manner of authority. It was evident the slaves had charge each of a particular lady for whom he was responsible.

As soon as these blacks had gathered their party and belongings all together, they loaded the tents and trunks two to a mule, and lifted the women into the high red saddles, always ridden astride; then, picking up their guns, they started on to the palace, leading the animals through the ancient gate and across the crowded town, shouting ‘Balak! Balak!’ Make way, make way! Once they had begun to move, the eunuchs paid no attention to any man, not deigning even to reply to the dog of a boatman who often followed them some hundred paces cursing them for having paid too little, sometimes nothing at all, when much was expected for ferrying the Lai-ell of the Sultan.

The caravan had been a long time on the road from Fez. Travelling only part of the day and camping early, it had taken a fortnight to come a distance little more than 150 miles. The Sultan had brought with him twenty of his favourites, trailing them across country rapidly, when he had hurried to this strategic place at the news that Mulai Hafid had been proclaimed Sultan at his southern capital and would probably race him to Rabat.

A FEW OF THE SULTAN’S WIVES.

But why Abdul Aziz brought with him any of his wives is a question. Perhaps they had more to do with it than had he; and perhaps it was for political reasons. At any rate (I have it from the Englishman quoted before) his harem bores him; to the songs and dances of all his beauties he much prefers the conversation of a single European who can tell him how a field gun works, what it is that makes the French—or any other—war balloon rise, and explain to him the pictures in the French and English weeklies to which he subscribes. He has here a motor-boat, which he keeps high and dry in a room in the palace, and the German engineer who makes its wheel go round is a frequent companion.

It is said in Morocco that while other Sultans visited their wives all in turn, showing favouritism to none, the present youthful High Shereef has cut off all but half a score, and never sees the mass of them except en masse. And it is said, too—among the many current stories regarding his European tendencies—that for these ten ladies he has spent thousands of pounds on Paris gowns and Paris hats to dress them in and see what European women look like. It naturally suggests itself that the poor fellow is hopelessly puzzled, and on a point that would of course catch his scientific mind: while the women of Paris are apparently built in two parts and pivoted together, those of his own dominions are constructed the other way. According to the ideas of the Orient the waist should be the place of largest circumference.