CHAPTER XIV

GOD SAVE THE SULTAN!

THE principal cause of the Moorish revolution, which threatens to terminate the reign of Abdul Aziz, was his tendency—up to a few months ago—to defy the religious prejudices which a long line of terrible predecessors had carefully nurtured in his people. The incident of the mosque of Mulai Idris at Fez was his culminating offence. To the uttermost corners of the Empire went the news that the young Sultan had defiled the most holy tomb of the country through causing to be taken by force from its sacred protection and murdered one of the Faithful who had slain a Christian dog. To the punishing wrath of the dishonoured saint and of the Almighty has been put down every calamity that has since befallen either the Sultan or the Empire; and the Moors will tell you that by this act has come the ruin of Morocco. It was in dramatic fashion that the feeling Driss, our man, stopped abruptly in the street when I mentioned the affair. We were nearing a picturesque little mosque with a leaning palm towering above it, and good old Driss was urging me to turn away and not to pass it—because he was a friend of mine and did not want me stoned. ‘Driss,’ said I, ‘they would not dare; the Sultan is here and they know that even a mosque won’t save them if they harm a European now.’ Driss stopped short and turned upon me. ‘You know that, Mr. Moore,’ he said with emphasis, ‘that about the Mulai Idris! That was the finish of Morocco!’

While with such breaches of the Moslem law Abdul Aziz has roused among the people a superstitious fear of consequences, he has also, by lesser defiances of recognised Moorish customs, sorely aggravated them. His many European toys—the billiard table, the costly photographic apparatus, the several bicycles, and the extravagant displays of fireworks—while harmless enough, were regarded by the Moors with no good grace. But worst of all these trivial things was, to the Moors, the young man’s evident lack of dignity. At times he would ride out alone and with Christians (who were his favourite companions), whereas the Sultans before him were hardly known to appear in public without the shade of the authoritative red umbrella.

An Englishman who knows Abdul Aziz and has for years advised him, tells me of a ride they took together accompanied only by their private servants, when the Court was formerly at Rabat, five years ago. The Sultan left the palace grounds with the hood of his jeleba drawn well down over his face, his servant likewise thoroughly covered in the garment that levels all Moors, men and women, to the same ghost-like appearance. Sultan and man met the Englishman outside the town walls at the ruins of Shella, a secluded place grown over with cactus bushes, and rode with him on into the country fifteen miles or more. On the way back they encountered a storm of rain, and drenched to the skin, their horses floundering in the slipping clay, they drew up at the back walls of the palace and tried to get an entrance by a gate always barred.

‘What shall we do?’ asked the Sultan.

‘Get your servant to climb the wall,’ said the Englishman.

‘No; you get yours,’ said Abdul Aziz, always contrary.

So the Englishman’s servant climbed the wall, dropped on the other side, and made his way to the palace, where he was promptly arrested and flogged for a lying thief, no one taking the trouble to go to see if his tale was true. After the Sultan and the Englishman had waited for some time, they rode round to another gate and entered. Then the unfortunate servant of the Christian was set free and given five dollars Hassani to heal his welted skin.

But things have changed. On the present visit of the Sultan to Rabat he no longer rides out except in great State; and this he does (on the advice partly of that particular Englishman of the wall adventure) every Friday regularly.

In September, while Abdul Aziz was on the road from Fez, hastening to anticipate his brother in getting to this, the war capital of Morocco (where, as the Moors say, the Sultan might listen with both ears, to the North and to the South), public criers from the rival camp of Mulai Hafid declared that Abdul Aziz was coming to the coast to be baptized a Christian under the guns of the infidel men-of-war. But this lie was easy to refute without the humiliation of a deliberate contradiction. Though at Fez it has always been the custom of the Sultan to worship at a private mosque within the grounds of his palace, it is likewise the custom for him at Rabat to go with a great fanfare and all his household and the Maghzen through lines of troops as long as he can muster, to a great public mosque in the open fields between the town’s outer and inner walls.

It was with a party of Europeans, mostly English correspondents, that I went to see the first Selamlik here. In the party there was W. B. Harris of the Times, and Wm. Maxwell of the Mail, as well as Allan Maclean, the brother of the Kaid. We had as an escort two soldiers from the British Consulate, without whom we could not have moved. The soldiers led the way shouting ‘Balak! balak!’ as we rode through the narrow crowded streets. But in all the throng no other Europeans were to be seen, until some way out we met at a cross-road and mingled for a moment with the delegation of French officials and correspondents, bound also for the great show.

Passing the Bab-el-Had, the Gate of Heads (fortunately not decorated at this time), the road led through grassy fields to a height from which is visible the whole palace enclosure. We could see, over the high white walls, the two lines of stacked muskets sweeping away in a long, opening arc from the narrow gate beside the mosque to the numerous doors of the low white-washed palace. Behind the guns the soldiers sat, generally in groups on the grass, only a few having life enough to play at any game. Considerably in the background were groups of women, garbed consistently in white, and heavily veiled.

Our soldiers, always glad to spur a horse, climbed through a break in the cactus that lined the road and led a hard canter down the slight, grassy slope, straight for one of the smaller gates. Two sentries seated on either side, perceiving us, rose nervously, retired and swung the doors in our faces, the rusty bars grating into place as we drew up. Our soldiers shouted, but got no answer, and we rode round to the Bab by the mosque, which could not be closed. As we drew up here a sentinel with arbitrary power let in two negro boys, clad each in a ragged shirt, riding together on a single dwarfed donkey not tall enough to keep their long, black, dangling legs out of the dust. But we could not pass—no; there was no use arguing, we could not pass. Slaves went in and beggars; the man was anxious, and shoved them in—but no; we, we were not French!

While our soldiers argued, the Frenchmen came up and passed in; then the guard, seeing we looked much like them, changed his mind and permitted us, too, to enter.

CHAINED NECK TO NECK—RECRUITS FOR THE SULTAN’S ARMY.

ABDUL AZIZ ENTERING HIS PALACE.

For some distance we passed between the lines of stacked guns, attracting the curious gaze of everybody, especially the women, who rose and came nearer the soldiers. One youth, a mulatto, got up and took a gun from a stack, and pretending to shove a cartridge into it, aimed directly at my head. The incident was, as one of the Englishmen suggested, somewhat boring.

Within a hundred yards of the palace we got behind the line and took up our stand. We had not long to wait. Shortly after the sun began to decline a twanging blast from a brassy cornet brought the field to its feet.

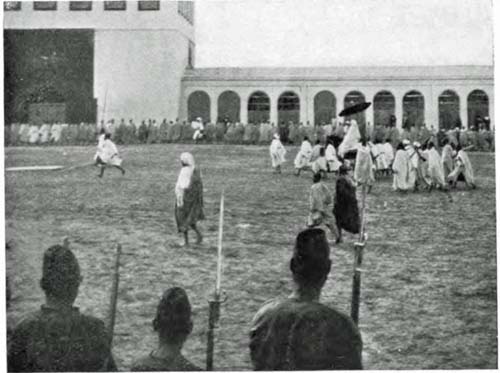

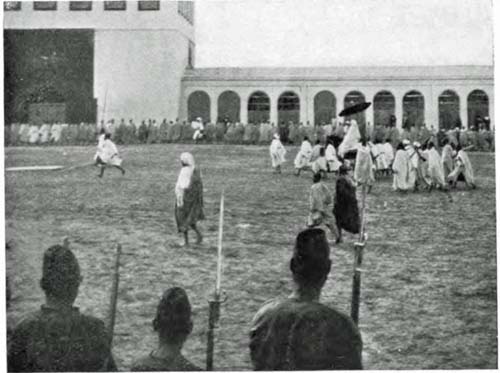

There was no hurry or scurry—there seldom is in Mohammedan countries. The soldiers took their guns, not with any order but without clashing; the women and children came up close; tribesmen, mounted, drew up behind. The Sultan’s band, in white, belted dresses, with knee skirts, bare legs, yellow slippers, and red fezzes, began to play a slow, impressive march—‘God save the King!’ with strange Oriental variations. It would not have been well if the Moors had known, and our soldier, for one, was amazed when we told him, that the band played the Christian Sultan’s hymn.

The mongrel soldiers, black and brown and white, slaves and freemen, presented arms uncertainly, as best they knew how; the white-robed women ‘coo-eed’ loud and shrill. A line of spear-bearers, all old men, passed at a short jog-trot; following them came six Arab horses, not very fine, but exceedingly fat, and richly caparisoned, led by skirted grooms; then the Sultan, immediately preceded and followed by private servants, likewise in white, except for their chief, a coal-black negro dressed in richest red. Beside the Sultan, who was robed in white and rode a white horse, walked on one side the bearer of the red parasol, and on the other a tall dark Arab who flicked a long scarf to keep flies off his Imperial Majesty. In and out of the ranks, disturbing whom he chose, ran a mad man, bellowing hideously, foaming at the mouth. This, on the part of Abdul Aziz, was indeed humouring the prejudices of the people.