IV

LONDON

THE PORT OF THE THAMES

That a town would group up on the lowest crossing of the Thames, once that crossing with its bridge or ferry was definitely established, is obvious enough. That this town would be important and large if there were a sufficient development of population and culture in the island is equally obvious. Both consequences would naturally follow from the topography of Britain. But that this town should become of such high importance in the European scheme and of such overwhelming importance in the national scheme; further, that this town should soon grow to be the second town in size of Western Europe, and at last by far the first, is not so immediate a conclusion from the known topographical conditions which brought it into being. That moral and material growth of London is due, of course, to the supremacy which London enjoyed and enjoys as a place of commerce. It is London as a market, and as a market the port of which was the Thames, which we must next consider, and we must ask ourselves upon what so considerable and historical a phenomenon has been based. The matter is usually dismissed by an affirmation lacking analysis and still more lacking proof. Our text-books are too often satisfied with telling us that “the exceptionally favourable position of London as a commercial centre” was at the root of the town’s greatness. The affirmation is perfectly true, but it does not provide its own explanation nor satisfy our curiosity as to why this position should have meant so much.

I think, indeed, that most observant people in reading this or similar phrases must, if they had any knowledge of the map, have been struck with the apparent disadvantages under which a site such as that of London suffers. It has not behind it a vast hinterland from which it should be able to gather raw material for export, nor is it a natural outlet for the various products of several different regions as is, for instance, the region surrounding the mouths of the Rhine. It is not central to the European scheme as Lyons was for so many centuries, and Paris for so many centuries more. It lies a long way up its stream from the sea. No system of converging waterways unites in its neighbourhood. There seems at first sight, therefore, no reason why London should have obtained more than a local importance.

When we consider its advantages as a general meeting-place for varied foreign commercial interests, a first view will profit us little. London is on no general European highway but lies ex-centric to Europe far upon the north and west of the general area which European culture covers; nor does its more central position since the discovery of the New World avail the argument, for the greatness of London was planted and its future continuance assured long before Europeans had known and developed the Western Continent. London, again, does not seem to invite commerce by lying upon the frontier common to two civilisations; it does not lie upon any economic boundary line as do the cities of the Levant and notably the cities of Palestine. It is, if we consider the economics of commerce during at any rate the first 1500 years of our era, almost at the edge of the world.

To explain the supremacy of London as a market more than one thesis is put forward for general acceptance which must, I think, be condemned. Thus we have the thesis that London occupies the position it does because it is almost in the centre of the land hemisphere. As a matter of fact the actual centre of that hemisphere is not far from the neighbourhood of Falmouth, and is at any rate within the limits of Britain. If we trace upon a globe a great circle or “equator” so as to include the greatest mass of land surface possible, we find our southern ports, and London amongst them, to lie near the Pole of such an Equator, and this argument has been of some weight with those who have not paused to consider what that “land hemisphere” means. If the climate of the world were everywhere equal and most of its soil equally productive, then the fact that the great estuary of the Thames lay almost central to the greatest mass of land would have its importance—though the mouths both of the Seine and of the Scheldt, of the Rhine, and for that matter of the Elbe, would not be so far distant as to explain the peculiar supremacy of London. But in the first place the most part of that mass of land did not enter into the commercial scheme until quite modern times, and secondly, the variations of its climate and of its productivity destroy the theory. Not far to the north of our port (relatively to so great a thing as the planet) lies that vast circle of uninhabited or hardly habitable frozen land which is not only almost useless for the purposes of exchange, but which also bars any passage of commerce across it. Not so very far to the south, again, runs the belt of desert east and west across Africa and Asia, the worst part of which, the widest, is also the nearest to us and is called the Sahara. It is of little use to have a central position between, say, Japan upon the one side and Cape Town upon the other, if the Greek Circle which connects us with Japan passes, as it does, through the Polar Ice. There are certain central positions which explain the supremacy of some particular site, but these positions are nearly always central to limited areas over which travel is uninterrupted. The great market of Nijni Novgorod in Russia is an example of this sort. Chicago in the United States of America is another. But London is no parallel to such cases as these, so far as the world or even Europe is concerned. It is fairly central (as we shall see) to what was once the chief wealth of England: it is ex-centric to all else.

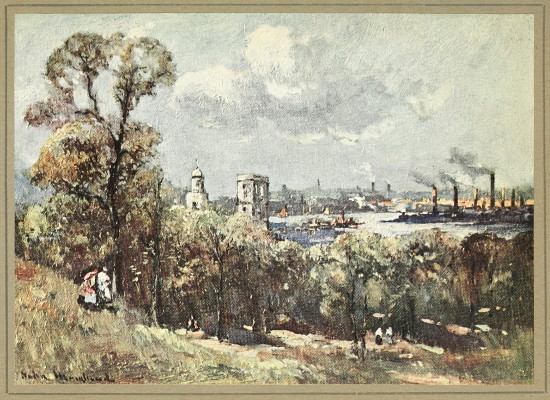

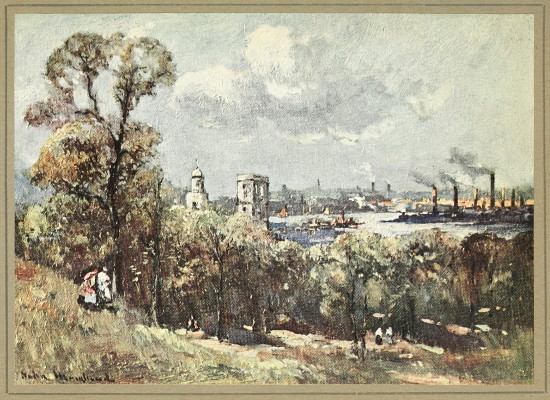

THE THAMES FROM GREENWICH PARK

Still less will the many arguments based upon fairly modern conditions solve the problem which confronts us. Thus the great export trade of modern England is mainly based upon coal. But the estuary of the Thames is not a natural place of export for coal. The political relations which necessarily bind this country to-day to other countries of the same speech throughout the New World have a vast effect in continuing and expanding our oversea exchanges, but all the ports natural to such ties lie upon our south or west. London does not face the New World. It looks away from it.

The truth is that the singular position of the Lower Thames as a terminal for international commerce, and of its port as an international market, must be sought in a medley of causes, the chief of which fall into two clear categories. We have first the causes which made London what it was before the transformation of commerce through the discoveries of the Renaissance and the later gigantic expansion which reposes upon modern facilities of communication. Once London is thus established as the second great city of the West, we have the later causes which permit it to continue in the enjoyment of that position, and to nourish it until the city whose port was the Thames became not the second but by far the first of all the great markets in wealth, population, and shipping.

I will take these two sets of causes separately.

As to the first, what made the greatness of the Thames as a port for London, and of London, therefore, as a market before the modern era of geographical discovery?

A natural market exists only where two natural conditions are present: ease of approach from without, and what may be called draining power from within.

I mean by ease of approach from without a natural facility for the arrival of goods from areas of production foreign to those of the market. And I mean by “draining power from within” some topographical or other condition which makes domestic produce run naturally towards the one centre of this market.

To these two natural conditions must be added two further political ones: first, one must have such a society connected with that market as gives it security, and, secondly, such a society as is organised by its activity and adventure for production or for exchange, or for both.

Now all these four conditions London enjoyed from a very early time. I have pointed out elsewhere, and shall point out again in these pages, the nature of the political security which London has enjoyed for so many centuries. It did not lie in any particularly peaceful character peculiar to the country as a whole, for while London was growing to greatness England was a continual theatre of domestic war. It lay in the great size which the city had attained, coupled with the breadth of its stream, and in its numerical proportion to the general population of which it was the capital. The fact that London was never besieged or sacked depended upon these characters, and they in turn, therefore, guaranteed that local security which is the first political necessity of a great and continuous market.

As to the commercial and productive character of the inhabitants of Britain, it escapes any material analysis. We must postulate it as a constant fact running through the known and recorded centuries of our history, and we may ascribe it according as we more love ease or veracity to whatever cause we feel most flattering or most true. No proof is possible. We can only say in this respect that certain areas of Europe have shown these characters for greater or less periods of time, and that others equally well endowed have not shown them, but have shown other characters perhaps as valuable.

The main fact in this connection is that whether the productive areas of Great Britain were exporting raw material (as during the most active centuries of the Middle Ages, when wool was our chief export), or whether (as later became the case) manufactured articles and coal were the stand-by of our oversea trade; whether we consider the period before or after the development of our carrying trade; whether we are concerned with an industrial or an agricultural England; whether we are observing late centuries in which the English showed a passionate interest in novelty and foreign adventure, or far more numerous early centuries in which they were indifferent to distant voyages—throughout the whole story with all its changes the productive area of the island has always maintained a high standard of wealth in comparison with its neighbours and its aptitude for exchange has always been equally high.

It is a point often neglected that the Norman Conquest, though of course it introduced a new and much more developed culture than Saxon England had possessed, did not find an impoverished land which the newcomers might “develop.” It found an exceedingly wealthy country according to the standards of the time; and the extent and variety of that wealth stands out very clearly in the narrative of contemporaries. Four centuries later, at the end of the Wars of the Roses, foreign observers make precisely the same comment. It is the packed wealth of South England filling its comparatively small area which the foreign envoy notes. We have a striking piece of evidence surviving before our eyes in the number, decoration and amplitude of our churches to which I have already alluded.

To continue the proof after the Tudors would be superfluous. There was even a phase, the beginning of which is to be found in the seventeenth century, the close of which we have unhappily seen in our own generation, when the wealth of England was so superior to that of any other rival that the material circumstances of life among the wealthier classes of the country seemed to belong to a different world from that of neighbouring nations, and when the economic supremacy of England was translated into a credit, a command of money, and an almost contemptuous security to which no other European people could pretend.

London, then, for all these centuries has enjoyed the two political conditions necessary to the establishment of a chief market, security and a productive area in the hands of a race by its genius inclined to exchange.

There remain the two natural conditions: ease of approach from without and “draining power” from within.

Now when we turn to these natural conditions we find that in the matter of ease of approach the Thames was unrivalled. London was, of course, far from the sea—a point with which I will deal in a moment—but there was no haven north of the Mediterranean which called so readily for commerce upon a large scale. Given the political conditions for a market—security and active powers of production and exchange—the Thames was as good a highway to that market as any that could be found. No vessels until quite modern times had to consider their draught or fear the entry of the river (at least, through channels which the pilots commanded), and once within the inland water a swinging tide was at the service of the ships. There were, within that inland stretch, no obstacles, no high intervening hills to becalm, no narrows or islands.

In this ease of access, again, must be reckoned the position of the Thames relatively to opposing ports. The wide funnel opened at a few hours’ sail from all that line of ports which begins with the mouth of the Seine and ends with the northernmost mouths of the Rhine. What we now call the coasts of Normandy, Picardy, Flanders, Belgium, and Holland lay, even at their extremes, within one double tide of the Thames.

It is true that they also lay equally convenient to any one of the lesser havens upon the Sussex, the Kent, the Essex, or the Norfolk coasts, but the ample space afforded by the river, the opportunity for a crowd of shipping, coupled with opportunities for inland trading, were to be found nowhere else in the south and east of the island as they were to be found up London River.

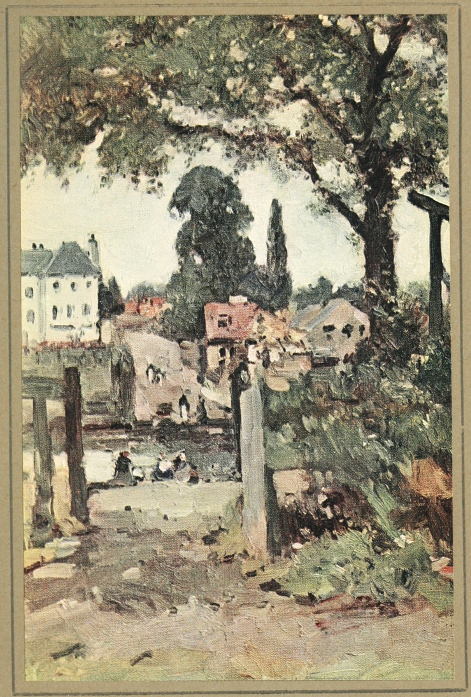

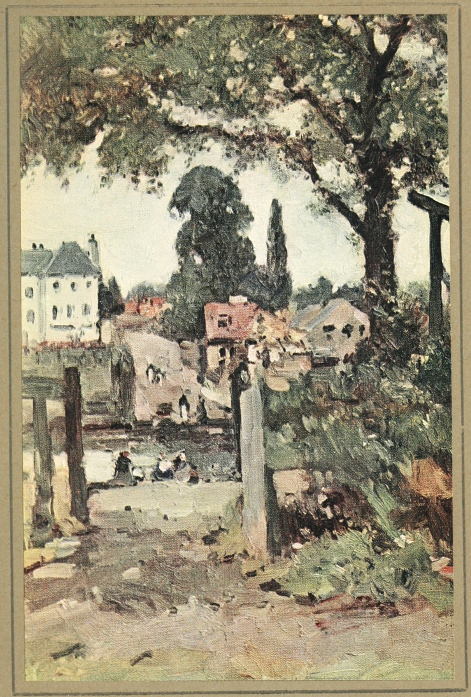

GRAVESEND

In this connection the use of the tide should be noted. By a peculiarity which has not been without its effect upon the history of the river the flood carries a man past the Kentish coast long past high water and indeed until a moment very close to that in which another tide, that from the North Sea, carries its sweep of water up the river. Thus, though the tide reach high water shortly after noon in Dover Harbour, a man outside will carry the stream with him all up past the Kentish coast until close upon five o’clock. He has but to get round Longnose and he finds this other tide serving him—a tide that has been making from three o’clock or thereabouts, coming in from the North Sea, and that will carry him right up river as long as the wind or daylight permits him to follow it; a tide that does not reach its height at Gravesend until eight that evening, or in the Pool of London until nine. In other words, the River of London afforded to the vessel coming in from the south a double tide which, clever picked up, gave a continuous voyage from the Channel right down into the sheltered water inland.

At this point it is interesting to consider why the principal harbours of the Middle Ages, in the north and west of Europe, at least, and upon tidal seas, so constantly developed not upon the coast itself, but at some distance up a stream or creek and inland.

Consider the examples: Havre comes late in the development of the Seine—the original port is Harfleur; Bristol stands up a tortuous and narrow channel well inland, and not upon the estuary of the Severn at all; Liverpool had its first nucleus four miles from the open sea; Preston quite twelve; Chester more than twenty, of which the last five or six were a narrow river above the estuary; Nantes is another striking example—something like one day’s sail from the sea; Antwerp, Rotterdam—Bruges itself lying those few miles inland upon its canal—follow the general rule; and so does Norwich, and so does Colchester, and so does Boston, and so does Glasgow; Bordeaux tells the same story, and so does the Royal Harbour of Montreuil. And in general, while a great number of smaller ports rose upon the very coast of the Atlantic, the North Sea, or the Channel, there seemed to be, until modern times at least, a tendency for the main depôts of sea-borne commerce to lie thus inland. Why was it?

We can only guess, but I would suggest that three factors combined to establish such a state of things: First, the little boats used for inland transport and the vehicles dependent upon roads and therefore upon bridges would seek a place of trans-shipment at some point upon the river where it had not yet become too broad or too rough, and so long as this place was accessible from the sea, the higher up river it was the better for them.

Next must be counted the security of a perfectly land-locked harbour for the smaller craft, which formed so much the largest part of maritime transport. A perfectly land-locked natural harbour upon the coast was a very rare thing. Let the stretch of water be only of the size of Southampton Water at its mouth, or of the Solent, and they would be wrecked in a high wind, but rivers everywhere afforded a secure protection when once one had entered their narrow channel.

Thirdly, we must consider the advantage which such sites presented against the attacks of pirates, and the better opportunities for defence which a considerable inland town possessed, with its resources in the surrounding fields and population over the smaller seaports.

In considering the first of these points we must remember that there was always a tendency for the central depôt or main commercial town to arise somewhat inland and to be served by subsidiary ports, if there were no direct access to it by water—and even if there were. Canterbury is an example of this, so is Winchester, so is Amiens, and so is Arras, and so is Caen, and so is Rennes, and a host of others.

In balancing the various advantages offered by various sites for the establishment of a market, a preponderating advantage must always be a position lying in the midst of several centres of production, and, since man is a land animal, these sites would normally lie inland. When they were served by a river so much the better; when they were served by a great and secure river, they could not fail to grow as London has grown.

As part of this ease of access must be reckoned, the peculiar character of the Thames, much more open to the wind than the Seine, not blocked by any island, affording once within the estuary a constant depth amply sufficient for all vessels until quite recent times.

But all this would not have given London its place had not a city established at the lowest crossing of the Thames exercised in a peculiar degree that “draining power” of which I have spoken.

We have seen how the system of British roads necessarily converged upon London, and if we consider one or two other features in English topography, we shall see why London provides a common depôt for nearly the whole of English exports in a fashion which no other city could show for any other equally large area of production.

Before the north of England was industrialised, three things were mainly required to establish what I have called the “draining” power of any market in the island. First, that it should be fairly central to all the south and Midlands; secondly, that it should afford a convenient centre of demand for various foreign products; thirdly, that it should be as close as possible to such continental markets as principally received our export.

Given those three conditions combined in any one place, and so far as the great mass of Britain was concerned, a point would be established to which would flow the main part of the produce which the Continent desired to purchase by exchange.

Observe how all these three conditions coincide in the case of London and of that Lower Thames which was its port.

When I say with regard to the first condition that the point we are seeking must be “central” to the south and east of the Island and to the Midlands, I am using a word which needs expansion. I mean that we must have a point to which the communications of commerce already lead, and one not too ex-centric to the area tapped.

Now at the first glance at the map London does give an impression of ex-centricity, of lying upon one side: and that towards the east and the south.

But when we begin to consider certain qualifying conditions, we shall find that London is fairly central, even geometrically, to the area in question, and that, when we are considering the economic “weight” of the various parts of this area, London may by a metaphor be said to be near the “centre of gravity” of such an area.

Cut off, in the first place, the Dumnonian Peninsula—that is, Devon and Cornwall,—the Welsh Highlands, and the Pennines. Consider (that is) South England, East Anglia, and the Midlands. You have an area roughly square, and about two hundred miles every way.

In drawing such a square, take for your extreme points Chester on the north-west, a point midway between Portland and Exmouth on the south-west; upon the north-east a point a little north of Cromer, and upon the south-east a point in the Straits of Dover, a trifle west of the line between Dungeness and Boulogne. Such a square includes a good deal that is outside our area, much of the estuary of the Severn, a strip of the Channel, a wedge of the North Sea and of the Wash, and a wedge of Pennine land to the north; but it also excludes a certain amount properly within our area as some of the richest parts of Kent and of Norfolk and Suffolk. We may therefore take this square for a fair average, and we shall see that even upon the test of distance London is not so ex-centric as might be imagined. Draw the two diagonals of this square, and you will find that London lies upon one of them at a distance of less than forty miles from the centre.

KINGSTON BRIDGE

When we consider something more than distance and think of London as the “centre of gravity” of the Midlands, the east and the south, we find it still more central for the centuries immediately preceding our own. Their staple export was wool. The pasturage of the chalk ranges runs right round London in the Chilterns and their extension into East Anglia, in the north and south Downs and the Uplands of Wiltshire, Hampshire, and Dorset. London is the obvious centre of all that triangle of chalk. It is again nearly equi-distant from the principal markets of Norfolk, of the Upper Trent valley, of Dorset, and of the Cotswolds. If we treat as exceptions the Lancashire and Yorkshire Plains (each with their local ports), the Vale Royal and the Lower Severn (each with its local port at Chester and at Bristol), London is very near the commercial centre of gravity of what remains. We must not forget that the Marlborough Downs and Salisbury Plain are but a few miles more distant from London Bridge than is the extremity of Kent. From the town of Pewsey to London Bridge as the crow flies is almost exactly eighty-eight miles. From the South Foreland the distance is not ten miles less. It needs but a slightly longer radius to include all the Warwickshire Midlands and very nearly all the county of Norfolk: all, of course, of Suffolk, of Essex, of Kent, Sussex, Surrey, and Hampshire.

London is geographically and commercially central at any rate to the older England—which was all that was needed for its establishment.

It was even more central when regarded as a nexus of communications.

How all the main roads centred there we have already seen. The roads alone would have given London a pre-eminence as a market above all other towns in Britain even if the Thames had dried up after their establishment. But the position was meanwhile further strengthened by the conditions of water carriage; and it is here that the meaning of the Thames as a whole appears, and the way in which the upper as well as the lower river has built up the greatness of London.

I have no space to show why and how water carriage was of supreme importance both in primitive times (that is, before the Roman civilisation came) and during the Dark Ages through which, in spite of decline, it survived. It should be sufficient to point out that in the decline of a civilisation, or in its absence, water carriage—suited to heavy burdens, requiring no repair of ways, and providing a mode of traction ready-made—is, wherever it is available, the chief economic factor of commerce.

Now when we recognise that the bulk of English wealth lay for centuries south and east of a line drawn from Exmouth to the Wash, and when we appreciate what the Thames valley is in that triangle, we shall see how necessarily the main market of the Thames was also the main market of England. The natural water communications of the south consist in a number of small streams, only one of which, the Salisbury Avon, may have been navigable for more than a dozen miles or so inland. East Anglia was better served, and particularly the northern area, which was drained by the three rivers converging upon Breydon Water. The northern part of that area was also fairly well served by the three parallel rivers of the Ouse, the Nen, and the Welland, but their service as a means of communication was handicapped by the nature of their entry into the sea through the Fens, and after that through the perils, sandbanks, and shallows of the Wash; while the good service of rivers along all the East Anglian coast had this drawback: that, as we there have nothing but a series of short systems, there was no water connection between one group of short valleys and another, not even one thought-out road. A dozen streams will carry produce from the sea to Worstead, to Norwich, to Beccles, to what was once the considerable port of Orford, to Ipswich, to Colchester, etc. But each avenue is a separate avenue. There is no “trunk” connecting the system.

With the Thames it is otherwise. Glance down the valley and see how one point after another, each the natural market of a whole district of its own, drains the produce from the north and the south of the river, to discharge it upon the main stream. From Lechlade (up to which point ran the “measure and the bushel of London”)[4] through Oxford, Abingdon, Wallingford, Reading, Marlow, the Middle Hythe (which we now call Maidenhead), and Windsor, you have a whole string of such centres, each gathering its own section’s produce from its scheme of roads, or of subsidiary streams, and turning the mass down seaward upon the “trunk” afforded by the Thames.

The Thames, therefore, with London as its port of transhipment between the inland communications and the sea, tapped the very heart of all that was wealthiest in England for fifteen hundred years, and all that commerce by river as by road drained upon London because London was “central” to exchange in the rich south and east of the island.

But, as we have seen, two further characters were attached to “draining” power. We must not only seek a point central for communications, we must also seek a point where there was a ready demand for import and a ready access to the best foreign markets.

Let us consider these two characters in their order:

A ready demand for import must exist either in a port itself or behind it, if that port is to develop into a great town and to acquire political importance. You have many instances, especially in contemporary commerce, of ports which do little more than export, and of other ports in which there is no demand for import, but which merely serve to pass the import inland. In the first case the international exchange is effected through imports at some other point. The clearing between export and import is a paper clearing, and the ships at the export point arrive in ballast—a drawback. In the second place, though a town may grow to some importance as a mere place of transhipment, it will never acquire the importance of a capital nor even of a great city—it will never have a great political place unless, round the handling of its imports destined for the interior, there grows up a considerable local power of demand for values. In other words, something of the imports transmitted through the town must “stick on the way.” Modern Liverpool is a good example of this. The primary economic function of modern Liverpool is still the transhipment of cotton to Lancashire just beyond its boundaries, but in the pursuit of this function Liverpool has claimed its tribute for now three generations, and so vast an accumulation of other activities connected with the port has grown up that even the digging of the Manchester Ship Canal, the effect of which was so much feared in Liverpool, seems to have been, if anything, a benefit to that town. What proportion the power of demand exercised for imported goods in Liverpool itself may bear to the total of values entering the port cannot be exactly calculated, but it is safe to say that the toll levied is not much less than one-fifth.

Now when to this power of demand created by the “sticking” at the point of transhipment or port of import, of goods coming from abroad, there is added the power of demand caused by the residence of government, of a court and of wealthy men apart from those who are wealthy through commerce, you get, of course, a very highly increased power of demand which makes of the port of import a specially great economic centre. A ship coming to such a port in order to take on board there the export in which it deals, can enter loaded with imports which are sure of a ready market.

SUNBURY

It so happens that London during all the centuries of its growth, and especially during those four hundred years of the Middle Ages which chiefly established its great position, was in exactly this position. Not only was it, as modern Liverpool is, a point of transhipment round which a vast quantity of subsidiary activities had grown, it was also close to the more or less permanent residence of the court, to what became the permanent seat of legislature, and to what was very early the permanent seat of the central courts of justice. The process continued uninterruptedly. After the loot of the church land of the endowments of the poor under the Tudors, the great palaces of the new aristocracy lined the Strand, and from the early seventeenth century—when this process was completed—onwards, the power of demand exercised by London alone and its local call for imports, has never ceased to grow, until to-day the position of London as an importing centre is due almost entirely to this character, next to its value as a clearing house: It is now only in a much less degree a point of transhipment.

The type of goods for which this local power of demand existed had also a very great effect in helping the growth of London through the traffic of the Thames.

Perhaps the principal import of the Middle Ages in value was that of wine. It was a luxurious import for which there was a local demand, especially where you had the residence of the wealthier people, and, what was exceedingly important, it was an import large in bulk. It meant that ships would come either in great numbers or in heavy tonnage, and this in itself suggested London as a place of export for their return, made a speculative voyage to London worth taking, and developed the warehousing space and the wharf space of the port. Later came coal, later still the tropical products, and last of all the great passenger traffic. But in every stage of the development London has exercised a local power of demand for that kind of import which demanded bulk in storage.

As to the second point, the easy access to the foreign port whither export was to be made, London was again especially favoured, in its point of growth. To-day it is no longer so, as we shall see in a moment. London is going forward with the momentum of its past. But until quite modern times London looked more favourably at the points to which England exported than did the other island ports, its rivals. It lay in the full focus of that long curve of the Norman, the Picard, the Flemish and Dutch coasts, which were the principal markets of the Middle Ages. Right opposite were the Flemish cities that bought English wool—the staple export—right opposite, also, the mouths of the Rhine for communication with the interior Germanies and, though a little more distant than the northern ports, agreeable to all that Baltic and North Sea trade which grew up with the close of the Middle Ages. The league of mercantile towns called Hanseatic had its depôt in London from the middle of the thirteenth century. The northern ports of England that lie a little nearer had no hinterland to feed their commerce, and London was, moreover, the best clearing-house and centre of general exchange for them in all the north and west. In this character it surpassed even Bruges.

When all these conditions changed—when the discovery of the New World, and of the Cape route to the Indies, when the growth of north-country industries and one hundred other factors had taken away from the site of London its old topographical supremacy, the port was so firmly established that it provided its own sources of vitality.

It is always so in the economic affairs of a town or of a nation. Material causes are discovered to be more powerful in the middle period of their growth; once the town or nation are rooted they nourish themselves. The River of London to-day is the capital example of this truth out of all Europe. A basin far too small for modern commerce, lying much too distantly up a river too narrow for modern commercial needs, dangerous of entry for ships of modern draft, and needing perpetual and enormous labour to keep it properly open, none the less preserves its place at the head of the ports of the world. As a depôt for commerce its wharves and docks extend to Tilbury, and that system of clearing which grew up naturally on the low gravel height above London Bridge, when the pool held all the shipping of the place and was a large and secure harbour, is still established on that same hill in the shape of the banks and the exchanges of the City of London, which cancel the exchanges, not of the pool below, but of I know not what fraction of the shipping of the whole world.

There is one last point to be considered in connection with London river as a port. It has been well made by Mr. Lyde in one of his short but remarkable geographical studies. The estuary of the Thames exactly faces that great and permanent frontier line between two parts of our European culture, upon either side of which lie contrasting speeches, traditions, and even religions.

That frontier roughly divides such areas of Western Europe as have continuously preserved the traditions of the Roman Empire from outer regions to the east and to the north, which only received the Christian religion and the Roman civilisation after the breakdown of central authority exercised from the Imperial city.

The estuary of the Thames opens like a funnel just opposite the point where this frontier between what some would call the “Teutonic” and “Latin” areas, reaches the sea.

It may not be at first sight apparent why a position of this kind is of capital commercial importance. The reason is rather moral than material, though it has its material element in the cheapness and expedition of carriage by sea.

Areas which differ in the type of their culture tend to become polarised one towards the other for the purposes of exchange. Each will tend to produce something that the other lacks. Now the exchange between two such areas will, of course, proceed actively enough across innumerable points lying upon the frontier between them, but it will not penetrate very far inland, if there is in competition with the inland routes a water route. Thus Arras will exchange easily enough with, say, Aix-la-Chapelle, Metz with Trèves or Frankfort, but what of Rouen and the Baltic, Bordeaux and the Frisian Lowlands, Brittany and Vendée and the German Plain? It is evident that if no friction existed a direct sea-borne commerce along the north-western coasts of Europe would effect these exchanges; but there does exist a friction, especially in early times, consisting in the ignorance and, as it were, the credulity, separating places so far distant in mileage and, what is more important, in culture. If, then, a half-way house is found sufficiently familiar to either party, that half-way house will tend to become in this new aspect out of so many, a centre of exchange—and this is precisely what happened to London. The North Sea and the Baltic were familiar with London—but then so was the Channel and the Bay of Biscay. London river attracted in this fashion a sheaf of trade routes, drawn from the north and east, another from the south and west. And so true is this that to the present day, and in one curious slight but emphatic modern instance, you can see the process at work. Travellers intent upon no purpose of commerce but merely upon an excursion will leave London river for Boulogne and Calais, sometimes for Dieppe and Havre; other travellers will leave the same facility of egress for the Scheldt and the Rhine and the Dutch ports and the Elbe. But, unless I am mistaken, the more obvious track of a passenger steamer route between the French ports and the Belgian, Dutch, and German ones does not exist save in the case of the great liners which touch at Cherbourg. A man desiring to go from Boulogne to Flushing by sea or from some lower French port to, say, Amsterdam, would very probably find his cheapest road to lie by way of going into the Thames and out of it. We must not exaggerate this element in the present position of London, where it is but a survival and that a small one: but in the past, and particularly in the establishment of the port at the end of the Dark Ages and the beginning of the Middle Ages, this ‘facing’ of London River towards the great political frontier line of Europe, was of capital importance. Scandinavia, the Baltic, Frisia, and the Dutch ports had all known their way to London for centuries when the Norman Conquest, and still more the succeeding Angevin monarchy, brought round into London River a new wealth of trade from the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne.

TWICKENHAM FERRY

In all that has preceded we have been considering London as the creation of the river in its civil aspect alone; it remains to consider the town and the stream in their effect upon the military history of the country, and to that I shall now turn.