CHAPTER VIII

TO THE INDIES NORTHWARD—ENGLISH, FRENCH, DUTCH, AND RUSSIAN ROUTES

The discovery of the New World had the most important consequences on the relative importance of the different nations of Europe. Hitherto the chief centres for over two thousand years had been round the shores of the Mediterranean, and, as we have seen, Venice, by her central position and extensive trade to the East, had become a world-centre during the latter Middle Ages. But after Columbus, and still more after Magelhaens, the European nations on the Atlantic were found to be closer to the New World, and, in a measure, closer to the Spice Islands, which they could reach all the way by ship, instead of having to pay expensive land freights. The trade routes through Germany became at once neglected, and it is only in the present century that she has at all recovered from the blow given to her by the discovery of the new sea routes in which she could not join. But to England, France, and the Low Countries the new outlook promised a share in the world's trade and affairs generally, which they had never hitherto possessed while the Mediterranean was the centre of commerce. If the Indies could be reached by sea, they were almost in as fortunate a position as Portugal or Spain. Almost as soon as the new routes were discovered the Northern nations attempted to utilise them, notwithstanding the Bull of Partition, which the French king laughed at, and the Protestant English and Dutch had no reason to respect. Within three years of the return of Columbus from his first voyage, Henry VII. employed John Cabot, a Venetian settled in Bristol, with his three sons, to attempt the voyage to the Indies by the North-West Passage. He appears to have re- discovered Newfoundland in 1497, and then in the following year, failing to find a passage there, coasted down North America nearly as far as Florida.

In 1534 Jacques Cartier examined the river St. Lawrence, and his discoveries were later followed up by Samuel de Champlain, who explored some of the great lakes near the St. Lawrence, and established the French rule in Canada, or Acadie, as it was then called.

Meanwhile the English had made an attempt to reach the Indies, still by a northern passage, but this time in an easterly direction. Sebastian Cabot, who had been appointed Grand Pilot of England by Edward VI., directed a voyage of exploration in 1553, under Sir Hugh Willoughby. Only one of these ships, with the pilot (Richard Chancellor) on board, survived the voyage, reaching Archangel, and then going overland to Moscow, where he was favourably received by the Czar of Russia, Ivan the Terrible. He was, however, drowned on his return, and no further attempt to reach Cathay by sea was attempted.

The North-West Passage seemed thus to promise better than that by the North-East, and in 1576 Martin Frobisher started on an exploring voyage, after having had the honour of a wave of Elizabeth's hand as he passed Greenwich. He reached Greenland, and then Labrador, and, in a subsequent voyage next year, discovered the strait named after him. His project was taken up by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on whom, with his brother Adrian, Elizabeth conferred the privilege of making the passage to China and the Moluccas by the north-westward, north-eastward, or northward route. At the same time a patent was granted him for discovering any lands unsettled by Christian princes. A settlement was made in St. John's, Newfoundland, but on the return voyage, near the Azores, Sir Humphrey's "frigate" (a small boat of ten men), disappeared, after he had been heard to call out, "Courage, my lads; we are as near heaven by sea as by land!" This happened in 1583.

Two years after, another expedition was sent out by the merchants of London, under John Davis, who, on this and two subsequent voyages, discovered several passages trending westward, which warranted the hope of finding a northwest passage. Beside the strait named after him, it is probable that on his third voyage, in 1587, he passed through the passage now named after Hudson. His discoveries were not followed up for some twenty years, when Henry Hudson was despatched in 1607 with a crew of ten men and a boy. He reached Spitzbergen, and reached 80° N., and in the following year reached the North (Magnetic) Pole, which was then situated at 75.22° N. Two of his men were also fortunate enough to see a mermaid—probably an Eskimo woman in her kayak. In a third voyage, in 1609, he discovered the strait and bay which now bear his name, but was marooned by his crew, and never heard of further. He had previously, for a time, passed into the service of the Dutch, and had guided them to the river named after him, on which New York now stands. The course of English discovery in the north was for a time concluded by the voyage of William Baffin in 1615, which resulted in the discovery of the land named after him, as well as many of the islands to the north of America.

Meanwhile the Dutch had taken part in the work of discovery towards the north. They had revolted against the despotism of Philip II., who was now monarch of both Spain and Portugal. At first they attempted to adopt a route which would not bring them into collision with their old masters; and in three voyages, between 1594 and 1597, William Barentz attempted the North-East Passage, under the auspices of the States-General. He discovered Cherry Island, and touched on Spitzbergen, but failed in the main object of his search; and the attention of the Dutch was henceforth directed to seizing the Portuguese route, rather than finding a new one for themselves.

The reason they were able to do this is a curious instance of Nemesis in history. Owing to the careful series of intermarriages planned out by Ferdinand of Arragon, the Portuguese Crown and all its possessions became joined to Spain in 1580 under Philip II., just a year after the northern provinces of the Netherlands had renounced allegiance to Spain. Consequently they were free to attack not alone Spanish vessels and colonies, but also those previously belonging to Portugal. As early as 1596 Cornelius Houtman rounded the Cape and visited Sumatra and Bantam, and within fifty, years the Dutch had replaced the Portuguese in many of their Eastern possessions. In 1614 they took Malacca, and with it the command of the Spice Islands; by 1658 they had secured full possession of Ceylon. Much earlier, in 1619, they had founded Batavia in Java, which they made the centre of their East Indian possessions, as it still remains.

The English at first attempted to imitate the Dutch in their East Indian policy. The English East India Company was founded by Elizabeth in 1600, and as early as 1619 had forced the Dutch to allow them to take a third share of the profits of the Spice Islands. In order to do this several English planters settled at Amboyna, but within four years trade rivalries had reached such a pitch that the Dutch murdered some of these merchants and drove the rest from the islands. As a consequence the English Company devoted its attention to the mainland of India itself, where they soon obtained possession of Madras and Bombay, and left the islands of the Indian Ocean mainly in possession of the Dutch. We shall see later the effect of this upon the history of geography, for it was owing to their possession of the East India Islands that the Dutch were practically the discoverers of Australia. One result of the Dutch East India policy has left its traces even to the present day. In 1651 they established a colony at the Cape of Good Hope, which only fell into English hands during the Napoleonic wars, when Napoleon held Holland.

Meanwhile the English had not lost sight of the possibilities of the North-East Passage, if not for reaching the Spice Islands, at any rate as a means of tapping the overland route to China, hitherto monopolised by the Genoese. In 1558 an English gentleman, named Anthony Jenkinson, was sent as ambassador to the Czar of Muscovy, and travelled from Moscow as far as Bokhara; but he was not very fortunate in his venture, and England had to be content for some time to receive her Indian and Chinese goods from the Venetian argosies as before. But at last they saw no reason why they should not attempt direct relations with the East. A company of Levant merchants was formed in 1583 to open out direct communications with Aleppo, Bagdad, Ormuz, and Goa. They were unsuccessful at the two latter places owing to the jealousy of the Portuguese, but they made arrangements for cheaper transit of Eastern goods to England, and in 1587 the last of the Venetian argosies, a great vessel of eleven hundred tons, was wrecked off the Isle of Wight. Henceforth the English conducted their own business with the East, and Venetian and Portuguese monopoly was at an end.

But the journeys of Chancellor and Jenkinson to the Court of Moscow had more far-reaching effects; the Russians themselves were thereby led to contemplate utilising their proximity to one of the best known routes to the Far East. Shortly after Jenkinson's visit, the Czar, Ivan the Terrible, began extending his dominions eastward, sending at first a number of troops to accompany the Russian merchant Strogonof as far as the Obi in search of sables. Among the troops were a corps of six thousand Cossacks commanded by one named Vassili Yermak, who, finding the Tartars an easy prey, determined at first to set up a new kingdom for himself. In 1579 he was successful in overcoming the Tartars and their chief town Sibir, near Tobolsk; but, finding it difficult to retain his position, determined to return to his allegiance to the Czar on condition of being supported. This was readily granted, and from that time onward the Russians steadily pushed on through to the unknown country of the north of Asia, since named after the little town conquered by Yermak, of which scarcely any traces now remain. As early as 1639 they had reached the Pacific under Kupilof. A force was sent out from Yakutz, on the Lena, in 1643, which reached the Amur, and thus Russians came for the first time in contact with the Chinese, and a new method of reaching Cathay was thus obtained, while geography gained the knowledge of the extent of Northern Asia. For, about the same time (in 1648), the Arctic Ocean was reached on the north shores of Siberia, and a fleet under the Cossack Dishinef sailed from Kolyma and reached as far as the straits known by the name of Behring. It was not, however, till fifty years afterwards, in 1696, that the Russians reached Kamtschatka.

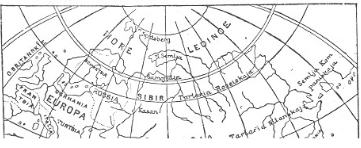

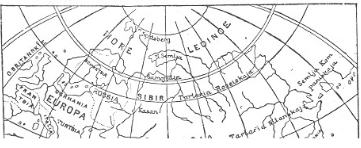

RUSSIAN MAP OF ASIA, 1737.

Notwithstanding the access of knowledge which had been gained by these successive bold pushes towards north and east, it still remained uncertain whether Siberia did not join on to the northern part of the New World discovered by Columbus and Amerigo, and in 1728 Peter the Great sent out an expedition under VITUS BEHRING, a Dane in the Russian service, with the express aim of ascertaining this point. He reached Kamtschatka, and there built two vessels as directed by the Czar, and started on his voyage northward, coasting along the land. When he reached a little beyond 67° N., he found no land to the north or east, and conceived he had reached the end of the continent. As a matter of fact, he was within thirty miles of the west coast of America; but of this he does not seem to have been aware, being content with solving the special problem put before him by the Czar. The strait thus discovered by Behring, though not known by him to be a strait, has ever since been known by his name. In 1741, however, Behring again set out on a voyage of discovery to ascertain how far to the east America was, and within a fortnight had come within sight of the lofty mountain named by him Mount St. Elias. Behring himself died upon this voyage, on an island also named after him; he had at last solved the relation between the Old and the New Worlds.

These voyages of Behring, however, belong to a much later stage of discovery than those we have hitherto been treating for the last three chapters. His explorations were undertaken mainly for scientific purposes, and to solve a scientific problem, whereas all the other researches of Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Dutch were directed to one end, that of reaching the Spice Islands and Cathay. The Portuguese at first started out on the search by the slow method of creeping down the coast of Africa; the Spanish, by adopting Columbus's bold idea, had attempted it by the western route, and under Magellan's still bolder conception had equally succeeded in reaching it in that way; the English and French sought for a north-west passage to the Moluccas; while the English and Dutch attempted a northeasterly route. In both directions the icy barrier of the north prevented success. It was reserved, as we shall see, for the present century to complete the North-West Passage under Maclure, and the North-East by Nordenskiold, sailing with quite different motives to those which first brought the mariners of England, France, and Holland within the Arctic Circle.

The net result of all these attempts by the nations of Europe to wrest from the Venetians the monopoly of the Eastern trade was to add to geography the knowledge of the existence of a New World intervening between the western shores of Europe and the eastern shores of Asia. We have yet to learn the means by which the New World thus discovered became explored and possessed by the European nations.

[Authorities: Cooley and Beazeley, John and Sebastian Cabot, 1898.]