CHAPTER VII

TO THE INDIES WESTWARD—THE SPANISH ROUTE—COLUMBUS AND MAGELLAN

While the Portuguese had, with slow persistency, devoted nearly a century to carrying out Prince Henry's idea of reaching the Indies by the eastward route, a bold yet simple idea had seized upon a Genoese sailor, which was intended to achieve the same purpose by sailing westward. The ancients, as we have seen, had recognised the rotundity of the earth, and Eratosthenes had even recognised the possibility of reaching India by sailing westward. Certain traditions of the Greeks and the Irish had placed mysterious islands far out to the west in the Atlantic, and the great philosopher Plato had imagined a country named Atlantis, far out in the Indian Ocean, where men were provided with all the gifts of nature. These views of the ancients came once more to the attention of the learned, owing to the invention of printing and the revival of learning, when the Greek masterpieces began to be made accessible in Latin, chiefly by fugitive Greeks from Constantinople, which had been taken by the Turks in 1453. Ptolemy's geography was printed at Rome in 1462, and with maps in 1478. But even without the maps the calculation which he had made of the length of the known world tended to shorten the distance between Portugal and Farther India by 2500 miles. Since his time the travels of Marco Polo had added to the knowledge of Europe the vast extent of Cathay and the distant islands of Zipangu (Japan), which would again reduce the distance by another 1500 miles. As the Greek geographers had somewhat under-estimated the whole circuit of the globe, it would thus seem that Zipangu was not more than 4000 miles to the west of Portugal. As the Azores were considered to be much farther off from the coast than they really were, it might easily seem, to an enthusiastic mind, that Farther India might be reached when 3000 miles of the ocean had been traversed.

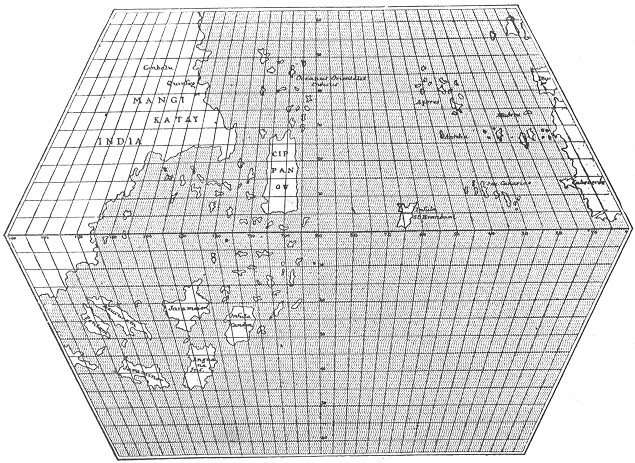

TOSCANELLI'S MAP (restored)

This was the notion that seized the mind of Christopher Columbus, born at Genoa in 1446, of humble parentage, his father being a weaver. He seems to have obtained sufficient knowledge to enable him to study the works of the learned, and of the ancients in Latin translations. But in his early years he devoted his attention to obtaining a practical acquaintance with seamanship. In his day, as we have seen, Portugal was the centre of geographical knowledge, and he and his brother Bartolomeo, after many voyages north and south, settled at last in Lisbon—his brother as a map-maker, and himself as a practical seaman. This was about the year 1473, and shortly afterwards he married Felipa Moñiz, daughter of Bartolomeo Perestrello, an Italian in the service of the King of Portugal, and for some time Governor of Madeira.

Now it chanced just at this time that there was a rumour in Portugal that a certain Italian philosopher, named Toscanelli, had put forth views as to the possibility of a westward voyage to Cathay, or China, and the Portuguese king had, through a monk named Martinez, applied to Toscanelli to know his views, which were given in a letter dated 25th June 1474. It would appear that, quite independently, Columbus had heard the rumour, and applied to Toscanelli, for in the latter's reply he, like a good business man, shortened his answer by giving a copy of the letter he had recently written to Martinez. What was more important and more useful, Toscanelli sent a map showing in hours (or degrees) the probable distance between Spain and Cathay westward. By adding the information given by Marco Polo to the incorrect views of Ptolemy about the breadth of the inhabited world, Toscanelli reduced the distance from the Azores to 52°, or 3120 miles. Columbus always expressed his indebtedness to Toscanelli's map for his guidance, and, as we shall see, depended upon it very closely, both in steering, and in estimating the distance to be traversed. Unfortunately this map has been lost, but from a list of geographical positions, with latitude and longitude, founded upon it, modern geographers have been able to restore it in some detail, and a simplified sketch of it may be here inserted, as perhaps the most important document in Columbus's career.

Certainly, whether he had the idea of reaching the Indies by a westward voyage before or not, he adopted Toscanelli's views with enthusiasm, and devoted his whole life henceforth to trying to carry them into operation.

He gathered together all the information he could get about the fabled islands of the Atlantic—the Island of St. Brandan, where that Irish saint found happy mortals; and the Island of Antilla, imagined by others, with its seven cities. He gathered together all the gossip he could hear—of mysterious corpses cast ashore on the Canaries, and resembling no race of men known to Europe; of huge canes, found on the shores of the same islands, evidently carved by man's skill. Curiously enough, these pieces of evidence were logically rather against the existence of a westward route to the Indies than not, since they indicated an unknown race, but, to an enthusiastic mind like Columbus's, anything helped to confirm him in his fixed idea, and besides, he could always reply that these material signs were from the unknown island of Zipangu, which Marco Polo had described as at some distance from the shores of Cathay.

He first approached, as was natural, the King of Portugal, in whose land he was living, and whose traditional policy was directed to maritime exploration. But the Portuguese had for half a century been pursuing another method of reaching India, and were not inclined to take up the novel idea of a stranger, which would traverse their long-continued policy of coasting down Africa. A hearing, however, was given to him, but the report was unfavourable, and Columbus had to turn his eyes elsewhere. There is a tradition that the Portuguese monarch and his advisers thought rather more of Columbus's ideas at first; and attempted secretly to put them into execution; but the pilot to whom they entrusted the proposed voyage lost heart as soon as he lost sight of land, and returned with an adverse verdict on the scheme. It is not known whether Columbus heard of this mean attempt to forestall him, but we find him in 1487 being assisted by the Spanish Court, and from that time for the next five years he was occupied in attempting to induce the Catholic monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, to allow him to try his novel plan of reaching the Indies. The final operations in expelling the Moors from Spain just then engrossed all their attention and all their capital, and Columbus was reduced to despair, and was about to give up all hopes of succeeding in Spain, when one of the great financiers, a converted Jew named Luis de Santaguel, offered to find means for the voyage, and Columbus was recalled.

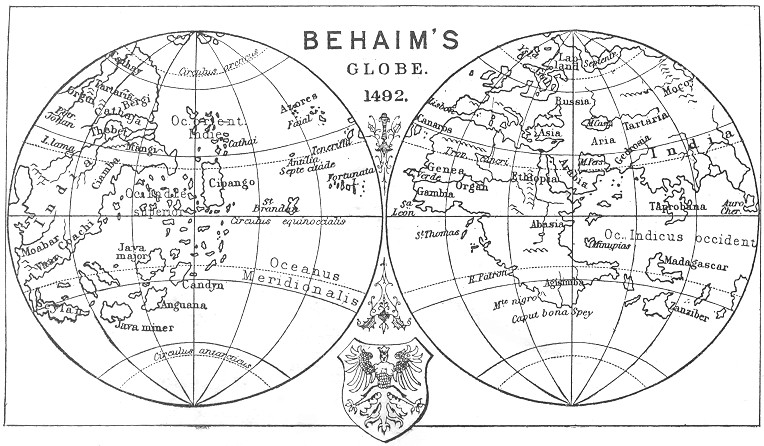

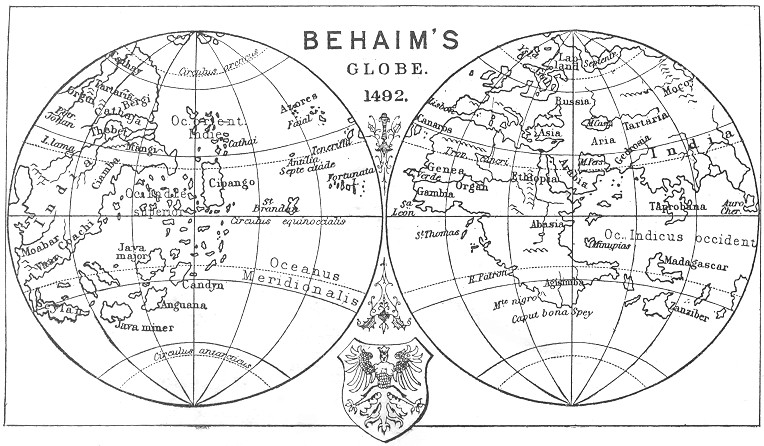

BEHAIM'S GLOBE. 1492.

On the 19th April 1492 articles were signed, by which Columbus received from the Spanish monarchs the titles of Admiral and Viceroy of all the lands he might discover, as well as one-tenth of all the tribute to be derived from them; and on Friday the 3rd August, of the same year, he set sail in three vessels, entitled the Santa Maria (the flagship), the Pinta, and the Nina. He started from the port of Palos, first for the Canary Islands. These he left on the 6th September, and steered due west. On the 13th of that month, Columbus observed that the needle of the compass pointed due north, and thus drew attention to the variability of the compass. By the 21st September his men became mutinous and tried to force him to return. He induced them to continue, and four days afterwards the cry of "Land! land!" was heard, which kept up their spirits for several days, till, on the 1st October, large numbers of birds were seen. By that time Columbus had reckoned that he had gone some 710 leagues from the Canaries, and if Zipangu were in the position that Tostanelli's map gave it, he ought to have been in its neighbourhood. It was reckoned in those days that a ship on an average could make four knots an hour, dead reckoning, which would give about 100 miles a day, so that Columbus might reckon on passing over the 3100 miles which he thought intervened between the Azores and Japan in about thirty-three days. All through the early days of October his courage was kept up by various signs of the nearness of land—birds and branches—while on the 11th October, at sunset, they sounded, and found bottom; and at ten o'clock, Columbus, sitting in the stern of his vessel, saw a light, the first sure sign of land after thirty-five days, and in near enough approximation to Columbus's reckoning to confirm him in the impression that he was approaching the mysterious land of Zipangu. Next morning they landed on an island, called by the natives Guanahain, and by Columbus San Salvador. This has been identified as Watling Island. His first inquiry was as to the origin of the little plates of gold which he saw in the ears of the natives. They replied that they came from the West— another confirmation of his impression. Steering westward, they arrived at Cuba, and afterwards at Hayti (St. Domingo). Here, however, the Santa Maria sank, and Columbus determined to return, to bring the good news, after leaving some of his men in a fort at Hayti. The return journey was made in the Nina in even shorter time to the Azores, but afterwards severe storms arose, and it was not till the 15th March 1493 that he reached Palos, after an absence of seven and a half months, during which everybody thought that he and his ships had disappeared.

He was naturally received with great enthusiasm by the Spaniards, and after a solemn entry at Barcelona he presented to Ferdinand and Isabella the store of gold and curiosities carried by some of the natives of the islands he had visited. They immediately set about fitting out a much larger fleet of seven vessels, which started from Cadiz, 25th September 1493. He took a more southerly course, but again reached the islands now known as the West Indies. On visiting Hayti he found the fort destroyed, and no traces of the men he had left there. It is needless for our purposes to go through the miserable squabbles which occurred on this and his subsequent voyages, which resulted in Columbus's return to Spain in chains and disgrace. It is only necessary for us to say that in his third voyage, in 1498, he touched on Trinidad, and saw the coast of South America, which he supposed to be the region of the Terrestrial Paradise. This was placed by the mediæval maps at the extreme east of the Old World. Only on his fourth voyage, in 1502, did he actually touch the mainland, coasting along the shores of Central America in the neighbourhood of Panama. After many disappointments, he died, 20th May 1506, at Valladolid, believing, as far as we can judge, to the day of his death, that what he had discovered was what he set out to seek—a westward route to the Indies, though his proud epitaph indicates the contrary:—

A Castilla y á Leon | To Castille and to Leon

Nuevo mondo dió Colon. | A NEW WORLD gave Colon.[1]

[Footnote 1: Columbus's Spanish name was Cristoval Colon.]

To this day his error is enshrined in the name we give to the Windward and Antilles Islands—West Indies: in other words, the Indies reached by the westward route. If they had been the Indies at all, they would have been the most easterly of them.

Even if Columbus had discovered a new route to Farther India, he could not, as we have seen, claim the merit of having originated the idea, which, even in detail, he had taken from Toscanelli. But his claim is even a greater one. He it was who first dared to traverse unknown seas without coasting along the land, and his example was the immediate cause of all the remarkable discoveries that followed his earlier voyages. As we have seen, both Vasco da Gama and Cabral immediately after departed from the slow coasting route, and were by that means enabled to carry out to the full the ideas of Prince Henry; but whereas, by the Portuguese method of coasting, it had taken nearly a century to reach the Cape of Good Hope, within thirty years of Columbus's first venture the whole globe had been circumnavigated.

The first aim of his successors was to ascertain more clearly what it was that Columbus had discovered. Immediately after Columbus's third, voyage, in 1498, and after the news of Vasco da Gama's successful passage to the Indies had made it necessary to discover some strait leading from the "West Indies" to India itself, a Spanish gentleman, named Hojeda, fitted out an expedition at his own expense, with an Italian pilot on board, named Amerigo Vespucci, and tried once more to find a strait to India near Trinidad. They were, of course, unsuccessful, but they coasted along and landed on the north coast of South America, which, from certain resemblances, they termed Little Venice (Venezuela). Next year, as we have seen, Cabral, in following Vasco da Gama, hit upon Brazil, which turned out to be within the Portuguese "sphere of influence," as determined by the line of demarcation.

But, three months previous to Cabral's touching upon Brazil, one of Columbus's companions on his first voyage, Vincenta Yanez Pinzon, had touched on the coast of Brazil, eight degrees south of the line, and from there had worked northward, seeking for a passage which would lead west to the Indies. He discovered the mouth of the Amazon, but, losing two of his vessels, returned to Palos, which he reached in September 1500.

This discovery of an unknown and unsuspected continent so far south of the line created great interest, and shortly after Cabral's return Amerigo Vespucci was sent out in 1501 by the King of Portugal as pilot of a fleet which should explore the new land discovered by Cabral and claim it for the Crown of Portugal. His instructions were to ascertain how much of it was within the line of demarcation. Vespucci reached the Brazilian coast at Cape St. Roque, and then explored it very thoroughly right down to the river La Plata, which was too far west to come within the Portuguese sphere. Amerigo and his companions struck out south-eastward till they reached the island of St. Georgia, 1200 miles east of Cape Horn, where the cold and the floating ice drove them back, and they returned to Lisbon, after having gone farthest south up to their time.

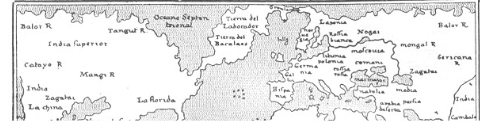

This voyage of Amerigo threw a new light upon the nature of the discovery made by Columbus. Whereas he had thought he had discovered a route to India and had touched upon Farther India, Amerigo and his companions had shown that there was a hitherto unsuspected land intervening between Columbus's discoveries and the long-desired Spice Islands of Farther India. Amerigo, in describing his discoveries, ventured so far as to suggest that they constituted a New World; and a German professor, named Martin Waldseemüller, who wrote an introduction to Cosmography in 1506, which included an account of Amerigo's discoveries, suggested that this New World should be called after him, AMERICA, after the analogy of Asia, Africa, and Europe. For a long time the continent which we now know as South America was called simply the New World, and was supposed to be joined on to the east coast of Asia. The name America was sometimes applied to it— not altogether inappropriately, since it was Amerigo's voyage which definitely settled that really new lands had been discovered by the western route; and when it was further ascertained that this new land was joined, not to Asia, but to another continent as large as itself, the two new lands were distinguished as North and South America.

AMERIGO VESPUCCI

It was, at any rate, clear from Amerigo's discovery that the westward route to the Spice Islands would have to be through or round this New World discovered by him, and a Portuguese noble, named Fernao Magelhaens, was destined to discover the practicability of this route. He had served his native country under Almeida and Albuquerque in the East Indies, and was present at the capture of Malacca in 1511, and from that port was despatched by Albuquerque with three ships to visit the far- famed Spice Islands. They visited Amboyna and Banda, and learned enough of the abundance and cheapness of the spices of the islands to recognise their importance; but under the direction of Albuquerque, who only sent them out on an exploring expedition, they returned to him, leaving behind them, however, one of Magelhaens' greatest friends, Francisco Serrao, who settled in Ternate and from time to time sent glowing accounts of the Moluccas to his friend Magelhaens. He in the meantime returned to Portugal, and was employed on an expedition to Morocco. He was not, however, well treated by the Portuguese monarch, and determined to leave his service for that of Charles V., though he made it a condition of his entering his service that he should make no discoveries within the boundaries of the King of Portugal, and do nothing prejudicial to his interests.

This was in the year 1517, and two years elapsed before Magelhaens started on his celebrated voyage. He had represented to the Emperor that he was convinced that a strait existed which would lead into the Indian Ocean, past the New World of Amerigo, and that the Spice Islands were beyond the line of demarcation and within the Spanish sphere of influence. There is some evidence that Spanish merchant vessels, trading secretly to obtain Brazil wood, had already caught sight of the strait afterwards named after Magelhaens, and certainly such a strait is represented upon Schoner's globes dated 1515 and 1520—earlier than Magelhaens' discovery. The Portuguese were fully aware of the dangers threatened to their monopoly of the spice trade—which by this time had been firmly established—owing to the presence of Serrao in Ternate, and did all in their power to dissuade Charles from sending out the threatened expedition, pointing out that they would consider it an unfriendly act if such an expedition were permitted to start. Notwithstanding this the Emperor persisted in the project, and on Tuesday, 20th September 1519, a fleet of five vessels, the Trinidad, St. Antonio, Concepcion, Victoria, and St. Jago, manned by a heterogeneous collection of Spaniards, Portuguese, Basques, Genoese, Sicilians, French, Flemings, Germans, Greeks, Neapolitans, Corfiotes, Negroes, Malays, and a single Englishman (Master Andrew of Bristol), started from Seville upon perhaps the most important voyage of discovery ever made. So great was the antipathy between Spanish and Portuguese that disaffection broke out almost from the start, and after the mouth of the La Plata had been carefully explored, to ascertain whether this was not really the beginning of a passage through the New World, a mutiny broke out on the 2nd April 1520, in Port St. Julian, where it had been determined to winter; for of course by this time the sailors had become aware that the time of the seasons was reversed in the Southern Hemisphere. Magelhaens showed great firmness and skill in dealing with the mutiny; its chief leaders were either executed or marooned, and on the 18th October he resumed his voyage. Meanwhile the habits and customs of the natives had been observed—their huge height and uncouth foot-coverings, for which Magelhaens gave them the name of Patagonians. Within three days they had arrived at the entrance of the passage which still bears Magelhaens' name. By this time one of the ships, the St Jago, had been lost, and it was with only four of his vessels—the Trinidad, the Victoria, the Concepcion. and the St. Antonio—that, Magelhaens began his passage. There are many twists and divisions in the strait, and on arriving at one of the partings, Magelhaens despatched the St. Antonio to explore it, while he proceeded with the other three ships along the more direct route. The pilot of the St. Antonio had been one of the mutineers, and persuaded the crew to seize this opportunity to turn back altogether; so that when Magelhaens arrived at the appointed place of junction, no news could be ascertained of the missing vessel; it went straight back to Portugal. Magelhaens determined to continue his search, even, he said, if it came to eating the leather thongs of the sails. It had taken him thirty-eight days to get through the Straits, and for four months afterwards Magelhaens continued his course through the ocean, which, from its calmness, he called Pacific; taking a north-westerly course, and thus, by a curious chance, only hitting upon a couple of small uninhabited islands throughout their whole voyage, through a sea which we now know to be dotted by innumerable inhabited islands. On the 6th March 1520 they had sighted the Ladrones, and obtained much-needed provisions. Scurvy had broken out in its severest form, and the only Englishman on the ships died at the Ladrones. From there they went on to the islands now known as the Philippines, one of the kings of which greeted them very favourably. As a reward Magelhaens undertook one of his local quarrels, and fell in an unequal fight at Mactan, 27th April 1521. The three vessels continued their course for the Moluccas, but the Concepcion proved so unseaworthy that they had to beach and burn her. They reached Borneo, and here Juan Sebastian del Cano was appointed captain of the Victoria.

FERDINAND MAGELLAN.

At last, on the 6th November 1521, they reached the goal of their journey, and anchored at Tidor, one of the Moluccas. They traded on very advantageous terms with the natives, and filled their holds with the spices and nutmegs for which they had journeyed so far; but when they attempted to resume their journey homeward, it was found that the Trinidad was too unseaworthy to proceed at once, and it was decided that the Victoria should start so as to get the east monsoon. This she did, and after the usual journey round the Cape of Good Hope, arrived off the Mole of Seville on Monday the 8th September 1522—three years all but twelve days from the date of their departure from Spain. Of the two hundred and seventy men who had started with the fleet, only eighteen returned in the Victoria. According to the ship's reckoning they had arrived on Sunday the 7th, and for some time it was a puzzle to account for the day thus lost.

Meanwhile the Trinidad, which had been left behind at the Moluccas, had attempted to sail back to Panama, and reached as far north as 43°, somewhere about longitude 175° W. Here provisions failed them, and they had to return to the Moluccas, where they were seized, practically as pirates, by a fleet of Portuguese vessels sent specially to prevent interference by the Spaniards with the Portuguese monopoly of the spice trade. The crew of the Trinidad were seized and made prisoners, and ultimately only four of them reached Spain again, after many adventures. Thirteen others, who had landed at the Cape de Verde Islands from the Victoria, may also be included among the survivors of the fleet, so that a total number of thirty-five out of two hundred and seventy sums up the number of the first circumnavigators of the globe.

The importance of this voyage was unique when regarded from the point of view of geographical discovery. It decisively clinched the matter with regard to the existence of an entirely New World independent from Asia. In particular, the backward voyage of the Trinidad (which has rarely been noticed) had shown that there was a wide expanse of ocean north of the line and east of Asia, whilst the previous voyage had shown the enormous extent of sea south of the line. After the circumnavigation of the Victoria it was clear to cosmographers that the world was much larger than had been imagined by the ancients; or rather, perhaps one may say that Asia was smaller than had been thought by the mediæval writers. The dogged persistence shown by Magelhaens in carrying out his idea, which turned out to be a perfectly justifiable one, raises him from this point of view to a greater height than Columbus, whose month's voyage brought him exactly where he thought he would find land according to Toscanelli's map. After Magelhaens, as will be seen, the whole coast lines of the world were roughly known, except for the Arctic Circle and for Australia.

The Emperor was naturally delighted with the result of the voyage. He granted Del Cano a pension, and a coat of arms commemorating his services. The terms of the grant are very significant: or, two cinnamon sticks saltire proper, three nutmegs and twelve cloves, a chief gules, a castle or; crest, a globe, bearing the motto, "Primus circumdedisti me" (thou wert the first to go round me); supporters, two Malay kings crowned, holding in the exterior hand a spice branch proper. The castle, of course, refers to Castile, but the rest of the blazon indicates the importance attributed to the voyage as resting mainly upon the visit to the Spice Islands. As we have already seen, however, the Portuguese recovered their position in the Moluccas immediately after the departure of the Victoria, and seven years later Charles V. gave up any claims he might possess through Magelhaens' visit.

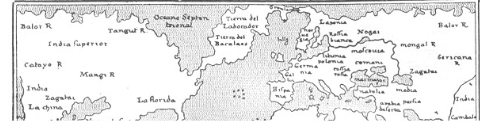

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO PTOLEMY OF 1548.

But for a long time afterwards the Spaniards still cast longing eyes upon the Spice Islands, and the Fuggers, the great bankers of Augsburg, who financed the Spanish monarch, for a long time attempted to get possession of Peru, with the scarcely disguised object of making it a "jumping-place" from which to make a fresh attempt at obtaining possession of the Moluccas. A modern parallel will doubtless occur to the reader.

There are thus three stages to be distinguished in the successive discovery and delimitation of the New World:—

(i.) At first Columbus imagined that he had actually reached Zipangu or Japan, and achieved the object of his voyage.

(ii.) Then Amerigo Vespucci, by coasting down South America, ascertained that there was a huge unknown land intervening even between Columbus' discoveries and the long-desired Spice Islands.

(iii.) Magelhaens clinches this view by traversing the Southern Pacific for thousands reaching the Moluccas.

There is still a fourth stage by which it was gradually discovered that the North-west of America was not joined on to Asia, but this stage was only gradually reached and finally determined by the voyages of Behring and Cook.

[Authorities: Justin Winsor, Christopher Columbus, 1894; Guillemard, Ferdinand Magellan, 1894.]