CHAPTER X

AUSTRALIA AND THE SOUTH SEAS—TASMAN AND COOK

If one looks at the west coast of Australia one is struck by the large number of Dutch names which are jotted down the coast. There is Hoog Island, Diemen's Bay, Houtman's Abrolhos, De Wit land, and the Archipelago of Nuyts, besides Dirk Hartog's Island and Cape Leeuwin. To the extreme north we find the Gulf of Carpentaria, and to the extreme south the island which used to be called Van Diemen's Land. It is not altogether to be wondered at that almost to the middle of this century the land we now call Australia was tolerably well known as New Holland. If the Dutch had struck the more fertile eastern shores of the Australian continent, it might have been called with reason New Holland to the present day; but there is scarcely any long coast-line of the world so inhospitable and so little promising as that of Western Australia, and one can easily understand how the Dutch, though they explored it, did not care to take possession of it.

But though the Dutch were the first to explore any considerable stretch of Australian coast, they were by no means the first to sight it. As early as 1542 a Spanish expedition under Luis Lopez de Villalobos, was despatched to follow up the discoveries of Magellan in the Pacific Ocean within the Spanish sphere of influence. He discovered several of the islands of Polynesia, and attempted to seize the Philippines, but his fleet had to return to New Spain. One of the ships coasted along an island to which was given the name of New Guinea, and was thought to be part of the great unknown southern land which Ptolemy had imagined to exist in the south of the Indian Ocean, and to be connected in some way with Tierra del Fuego. Curiosity was thus aroused, and in 1606 Pedro de Quiros was despatched on a voyage to the South Seas with three ships. He discovered the New Hebrides, and believed it formed part of the southern continent, and he therefore named it Australia del Espiritu Santo, and hastened home to obtain the viceroyalty of this new possession. One of his ships got separated from him, and the commander, Luys Vaz de Torres, sailed farther to the south-west, and thereby learned that the New Australia was not a continent but an island. He proceeded farther till he came to New Guinea, which he coasted along the south coast, and seeing land to the south of him, he thus passed through the straits since named after him, and was probably the first European to see the continent of Australia. In the very same year (1606) the Dutch yacht named the Duyfken is said to have coasted along the south and west coasts of New Guinea nearly a thousand miles, till they reached Cape Keerweer, or "turn again." This was probably the north-west coast of Australia. In the first thirty years of the seventeenth century the Dutch followed the west coast of Australia with as much industry as the Portuguese had done with the west coast of Africa, leaving up to the present day signs of their explorations in the names of islands, bays, and capes. Dirk Hartog, in the Endraaght, discovered that Land which is named after his ship, and the cape and roadstead named after himself, in 1616. Jan Edels left his name upon the western coast in 1619; while, three years later, a ship named the Lioness or Leeuwin reached the most western point of the continent, to which its name is still attached. Five years later, in 1627, De Nuyts coasted round the south coast of Australia; while in the same year a Dutch commander named Carpenter discovered and gave his name to the immense indentation still known as the Gulf of Carpentaria.

But still more important discoveries were made in 1642 by an expedition sent out from Batavia under ABEL JANSSEN TASMAN to investigate the real extent of the southern land. After the voyages of the Leeuwin and De Nuyts it was seen that the southern coast of the new land trended to the east, instead of working round to the west, as would have been the case if Ptolemy's views had been correct. Tasman's problem was to discover whether it was connected with the great southern land assumed to lie to the south of South America. Tasman first sailed from Mauritius, and then directing his course to the south-east, going much more south than Cape Leeuwin, at last reached land in latitude 43.30° and longitude 163.50°. This he called Van Diemen's Land, after the name of the Governor-General of Batavia, and it was assumed that this joined on to the land already discovered by De Nuyts. Sailing farther to the eastward, Tasman came out into the open sea again, and thus appeared to prove that the newly discovered land was not connected with the great unknown continent round the south pole.

But he soon came across land which might possibly answer to that description, and he called it Staaten Land, in honour of the States-General of the Netherlands. This was undoubtedly some part of New Zealand. Still steering eastward, but with a more northerly trend, Tasman discovered several islands in the Pacific, and ultimately reached Batavia after touching on New Guinea. His discoveries were a great advance on previous knowledge; he had at any rate reduced the possible dimensions of the unknown continent of the south within narrow limits, and his discoveries were justly inscribed upon the map of the world cut in stone upon the new Staathaus in Amsterdam, in which the name New Holland was given by order of the States-General to the western part of the "terra Australis." When England for a time became joined on to Holland under the rule of William III., William Dampier was despatched to New Holland to make further discoveries. He retraced the explorations of the Dutch from Dirk Hartog's Bay to New Guinea, and appears to have been the first European to have noticed the habits of the kangaroo; otherwise his voyage did not add much to geographical knowledge, though when he left the coasts of New Guinea he steered between New England and New Ireland.

As a result of these Dutch voyages the existence of a great land somewhere to the south-east of Asia became common property to all civilised men. As an instance of this familiarity many years before Cook's epoch-making voyages, it may be mentioned that in 1699 Captain Lemuel Gulliver (in Swift's celebrated romance) arrived at the kingdom of Lilliput by steering north-west from Van Diemen's Land, which he mentions by name. Lilliput, it would thus appear, was situated somewhere in the neighbourhood of the great Bight of Australia. This curious mixture of definite knowledge and vague ignorance on the part of Swift exactly corresponds to the state of geographical knowledge about Australia in his days, as is shown in the preceding map of those parts of the world, as given by the great French cartographer D'Anville in 1745 (p. 157).

These discoveries of the Spanish and Dutch were direct results and corollaries of the great search for the Spice Islands, which has formed the main subject of our inquiries. The discoveries were mostly made by ships fitted out in the Malay archipelago, if not from the Spice Islands themselves. But at the beginning of the eighteenth century new motives came into play in the search for new lands; by that time almost the whole coast-line of the world was roughly known. The Portuguese had coasted Africa, the Spanish South America, the English most of the east of North America, while Central America was known through the Spaniards. Many of the islands of the Pacific Ocean had been touched upon, though not accurately surveyed, and there remained only the north-west coast of America and the north-east coast of Asia to be explored, while the great remaining problem of geography was to discover if the great southern continent assumed by Ptolemy existed, and, if so, what were its dimensions. It happened that all these problems of coastline geography, if we may so call it, were destined to be solved by one man, an Englishman named JAMES COOK, who, with Prince Henry, Magellan, and Tasman, may be said to have determined the limits of the habitable land.

His voyages were made in the interests, not of trade or conquest, but of scientific curiosity; and they were, appropriately enough, begun in the interests of quite a different science than that of geography. The English astronomer Halley had left as a sort of legacy the task of examining the transit of Venus, which he predicted for the year 1769, pointing out its paramount importance for determining the distance of the sun from the earth. This transit could only be observed in the southern hemisphere, and it was in order to observe it that Cook made his first voyage of exploration.

There was a double suitability in the motive of Cook's first voyage. The work of his life could only have been carried out owing to the improvement in nautical instruments which had been made during the early part of the eighteenth century. Hadley had invented the sextant, by which the sun's elevation could be taken with much more ease and accuracy than with the old cross-staff, the very rough gnomon which the earlier navigators had to use. Still more important for scientific geography was the improvement that had taken place in accurate chronometry. To find the latitude of a place is not so difficult—the length of the day at different times of the year will by itself be almost enough to determine this, as we have seen in the very earliest history of Greek geography—but to determine the longitude was a much more difficult task, which in the earlier stages could only be formed by guesswork and dead reckonings.

But when clocks had been brought to such a pitch of accuracy that they would not lose but a few seconds or minutes during the whole voyage, they could be used to determine the difference of local time between any spot on the earth's surface and that of the port from which the ship sailed, or from some fixed place where the clock could be timed. The English government, seeing the importance of this, proposed the very large reward of £10,000 for the invention of a chronometer which would not lose more than a stated number of minutes during a year. This prize was won by John Harrison, and from this time onward a sea-captain with a minimum of astronomical knowledge was enabled to know his longitude within a few minutes. Hadley's sextant and Harrison's chronometer were the necessary implements to enable James Cook to do his work, which was thus, both in aim and method, in every way English.

James Cook was a practical sailor, who had shown considerable intelligence in sounding the St. Lawrence on Wolfe's expedition, and had afterwards been appointed marine surveyor of Newfoundland. When the Royal Society determined to send out an expedition to observe the transit of Venus, according to Halley's prediction, they were deterred from entrusting the expedition to a scientific man by the example of Halley himself, who had failed to obtain obedience from sailors on being entrusted with the command. Dalrymple, the chief hydrographer of the Admiralty, who had chief claims to the command, was also somewhat of a faddist, and Cook was selected almost as a dernier ressort. The choice proved an excellent one. He selected a coasting coaler named the Endeavour, of 360 tons, because her breadth of beam would enable her to carry more stores and to run near coasts. Just before they started Captain Wallis returned from a voyage round the world upon which he had discovered or re-discovered Tahiti, and he recommended this as a suitable place for observing the transit.

Cook duly arrived there, and on the 3rd of June 1769 the main object of the expedition was fulfilled by a successful observation. But he then proceeded farther, and arrived soon at a land which he saw reason to identify with the Staaten Land of Tasman; but on coasting along this, Cook found that, so far from belonging to a great southern continent, it was composed of two islands, between which he sailed, giving his name to the strait separating them. Leaving New Zealand on the 31st of March 1770, on the 20th of the next month he came across another land to the westward, hitherto unknown to mariners. Entering an inlet, he explored the neighbourhood with the aid of Mr. Joseph Banks, the naturalist of the expedition. He found so many plants new to him, that the bay was termed Botany Bay.

He then coasted northward, and nearly lost his ship upon the great reef running down the eastern coast; but by keeping within it he managed to reach the extreme end of the land in this direction, and proved that it was distinct from New Guinea. In other words, he had reached the southern point of the strait named after Torres. To this immense line of coast Cook gave the name of New South Wales, from some resemblance that he saw to the coast about Swansea. By this first voyage Cook had proved that neither New Holland nor Staaten Land belonged to the great Antarctic continent, which remained the sole myth bequeathed by the ancients which had not yet been definitely removed from the maps. In his second voyage, starting in 1772, he was directed to settle finally this problem. He went at once to the Cape of Good Hope, and from there started out on a zigzag journey round the Southern Pole, poking the nose of his vessel in all directions as far south as he could reach, only pulling up when he touched ice. In whatever direction he advanced he failed to find any trace of extensive land corresponding to the supposed Antarctic continent, which he thus definitely proved to be non- existent. He spent the remainder of this voyage in rediscovering various sets of archipelagos which preceding Spanish, Dutch, and English navigators had touched, but had never accurately surveyed. Later on Cook made a run across the Pacific from New Zealand to Cape Horn without discovering any extensive land, thus clinching the matter after three years' careful inquiry. It is worthy of remark that during that long time he lost but four out of 118 men, and only one of them by sickness.

Only one great problem to maritime geography still remained to be solved, that of the north-west passage, which, as we have seen, had so frequently been tried by English navigators, working from the east through Hudson's Bay. In 1776 Cook was deputed by George III. to attempt the solution of this problem by a new method. He was directed to endeavour to find an opening on the north-west coast of America which would lead into Hudson's Bay. The old legend of Juan de Fuca's great bay still misled geographers as to this coast. Cook not alone settled this problem, but, by advancing through Behring Strait and examining both sides of it, determined that the two continents of Asia and America approached one another as near as thirty-six miles. On his return voyage he landed at Owhyee (Hawaii), where he was slain in 1777, and his ships returned to England without adding anything further to geographical knowledge.

Cook's voyages had aroused the generous emulation of the French, who, to their eternal honour, had given directions to their fleet to respect his vessels wherever found, though France was at that time at war with England. In 1783 an expedition was sent, under François de la Pérouse, to complete Cook's work. He explored the north-east coast of Asia, examined the island of Saghalien, and passed through the strait between it and Japan, often called by his name. In Kamtschatka La Pérouse landed Monsieur Lesseps, who had accompanied the expedition as Russian interpreter, and sent home by him his journals and surveys. Lesseps made a careful examination of Kamtschatka himself, and succeeded in passing overland thence to Paris, being the first European to journey completely across the Old World from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. La Pérouse then proceeded to follow Cook by examining the coast of New South Wales, and to his surprise, when entering a fine harbour in the middle of the coast, found there English ships engaged in settling the first Australian colony in 1787. After again delivering his surveys to be forwarded by the Englishmen, he started to survey the coast of New Holland, but his expedition was never heard of afterwards. As late as 1826 it was discovered that they had been wrecked on Vanikoro, an island near the Fijis.

We have seen that Cook's exploration of the eastern coast of Australia was soon followed up by a settlement. A number of convicts were sent out under Captain Philips to Botany Bay, and from that time onward English explorers gradually determined with accuracy both the coast-line and the interior of the huge stretch of land known to us as Australia. One of the ships that had accompanied Cook on his second voyage had made a rough survey of Van Diemen's Land, and had come to the conclusion that it joined on to the mainland. But in 1797, Bass, a surgeon in the navy, coasted down from Port Jackson to the south in a fine whale boat with a crew of six men, and discovered open sea running between the southernmost point and Van Diemen's Land; this is still known as Bass' Strait. A companion of his, named Flinders, coasted, in 1799, along the south coast from Cape Leeuwin eastward, and on this voyage met a French ship at Encounter Bay, so named from the rencontre. Proceeding farther, he discovered Port Philip; and the coast-line of Australia was approximately settled after Captain P. P. King in four voyages, between 1817 and 1822, had investigated the river mouths.

THE EXPLORATION OF AUSTRALIA.

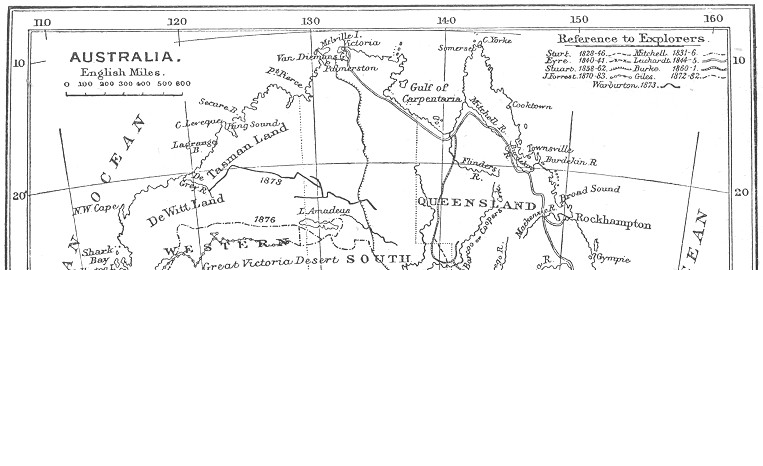

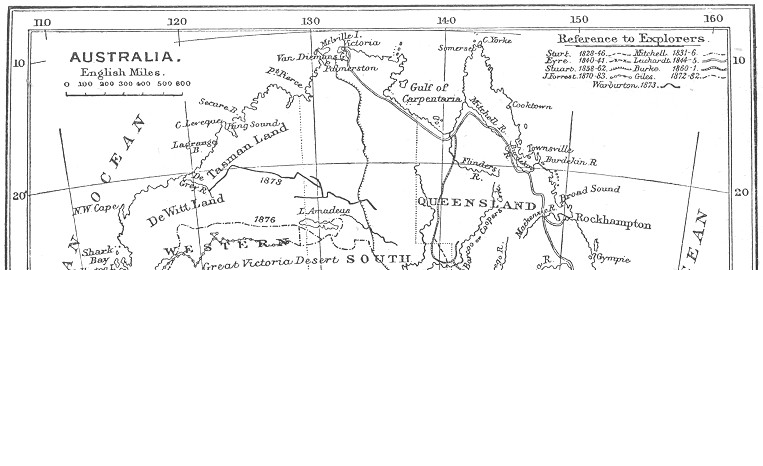

The interior now remained to be investigated. On the east coast this was rendered difficult by the range of the Blue Mountains, honeycombed throughout with huge gullies, which led investigators time after time into a cul-de-sac; but in 1813 Philip Wentworth managed to cross them, and found a fertile plateau to the westward. Next year Evans discovered the Lachlan and Macquarie rivers, and penetrated farther into the Bathurst plains. In 1828-29 Captain Sturt increased the knowledge of the interior by tracing the course of the two great rivers Darling and Murray. In 1848 the German explorer Leichhardt lost his life in an attempt to penetrate the interior northward; but in 1860 two explorers, named Burke and Wills, managed to pass from south to north along the east coast; while, in the four years 1858 to 1862, John M'Dowall Stuart performed the still more difficult feat of crossing the centre of the continent from south to north, in order to trace a course for the telegraphic line which was shortly afterwards erected. By this time settlements had sprung up throughout the whole coast of Eastern Australia, and there only remained the western desert to be explored. This was effected in two journeys of John Forrest, between 1868 and 1874, who penetrated from Western Australia as far as the central telegraphic line; while, between 1872 and 1876, Ernest Giles performed the same feat to the north. Quite recently, in 1897, these two routes were joined by the journey of the Honourable Daniel Carnegie from the Coolgardie gold fields in the south to those of Kimberley in the north. These explorations, while adding to our knowledge of the interior of Australia, have only confirmed the impression that it was not worth knowing.

[Authorities: Rev. G. Grimm, Discovsry and Exploration of Australia (Melbourne, 1888); A. F. Calvert, Discovery of Australia, 1893; Exploration of Australia, 1895; Early Voyages to Australia, Hakluyt Society.]