CHAPTER XI

EXPLORATION AND PARTITION OF AFRICA: PARK—LIVINGSTONE— STANLEY

We have seen how the Portuguese had slowly coasted along the shore of Africa during the fifteeenth century in search of a way to the Indies. By the end of the century mariners portulanos gave a rude yet effective account of the littoral of Africa, both on the west and the eastern side. Not alone did they explore the coast, but they settled upon it. At Amina on the Guinea coast, at Loando near the Congo, and at Benguela on the western coast, they established stations whence to despatch the gold and ivory, and, above all, the slaves, which turned out to be the chief African products of use to Europeans. On the east coast they settled at Sofala, a port of Mozambique; and in Zanzibar they possessed no less than three ports, those first visited by Vasco da Gama and afterwards celebrated by Milton in the sonorous line contained in the gorgeous geographical excursus in the Eleventh Book—

"Mombaza and Quiloa and Melind."

-Paradise Lost, xi. 339.

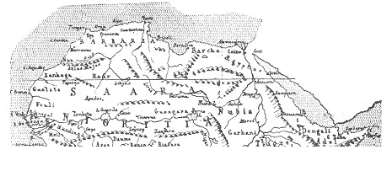

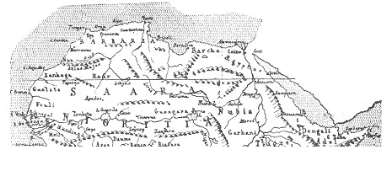

It is probable that, besides settling on the coast, the Portuguese from time to time made explorations into the interior. At any rate, in some maps of the sixteenth and seventeenth century there is shown a remarkable knowledge of the course of the Nile. We get it terminated in three large lakes, which can be scarcely other than the Victoria and Albert Nyanza, and Tanganyika. The Mountains of the Moon also figure prominently, and it was only almost the other day that Mr. Stanley re-discovered them. It is difficult, however, to determine how far these entries on the Portuguese maps were due to actual knowledge or report, or to the traditions of a still earlier knowledge of these lakes and mountains; for in the maps accompanying the early editions of Ptolemy we likewise obtain the same information, which is repeated by the Arabic geographers, obviously from Ptolemy, and not from actual observation. When the two great French cartographers Delisle and D'Anville determined not to insert anything on their maps for which they had not some evidence, these lakes and mountains disappeared, and thus it has come about that maps of the seventeenth century often appear to display more knowledge of the interior of Africa than those of the beginning of the nineteenth, at least with regard to the sources of the Nile.

African exploration of the interior begins with the search for the sources of the Nile, and has been mainly concluded by the determination of the course of the three other great rivers, the Niger, the Zambesi, and the Congo. It is remarkable that all four rivers have had their course determined by persons of British nationality. The names of Bruce and Grant will always be associated with the Nile, that of Mungo Park with the Niger, Dr. Livingstone with the Zambesi, and Mr. Stanley with the Congo. It is not inappropriate that, except in the case of the Congo, England should control the course of the rivers which her sons first made accessible to civilisation.

DAPPER'S MAP OF AFRICA, 1676.

We have seen that there was an ancient tradition reported by Herodotus, that the Nile trended off to the west and became there the river Niger; while still earlier there was an impression that part of it at any rate wandered eastward, and some way joined on to the same source as the Tigris and Euphrates at least that seems to be the suggestion in the biblical account of Paradise. Whatever the reason, the greatest uncertainty existed as to the actual course of the river, and to discover the source of the Nile was for many centuries the standing expression for performing the impossible. In 1768, James Bruce, a Scottish gentleman of position, set out with the determination of solving this mystery—a determination which he had made in early youth, and carried out with characteristic pertinacity. He had acquired a certain amount of knowledge of Arabic and acquaintance with African customs as Consul at Algiers. He went up the Nile as far as Farsunt, and then crossed the desert to the Red Sea, went over to Jedda, from which he took ship for Massowah, and began his search for the sources of the Nile in Abyssinia. He visited the ruins of Axum, the former capital, and in the neighbourhood of that place saw the incident with which his travels have always been associated, in which a couple of rump- steaks were extracted from a cow while alive, the wound sewn up, and the animal driven on farther.

Here, guided by some Gallas, he worked his way up the Blue Nile to the three fountains, which he declared to be the true sources of the Nile, and identified with the three mysterious lakes in the old maps. From there he worked his way down the Nile, reaching Cairo in 1773. Of course what he had discovered was merely the source of the Blue Nile, and even this had been previously visited by a Portuguese traveller named Payz. But the interesting adventures which he experienced, and the interesting style in which he told them, aroused universal attention, which was perhaps increased by the fact that his journey was undertaken purely from love of adventure and discovery. The year 1768 is distinguished by the two journeys of James Cook and James Bruce, both of them expressly for purposes of geographical discovery, and thus inaugurating the era of what may be called scientific exploration. Ten years later an association was formed named the African Association, expressly intended to explore the unknown parts of Africa, and the first geographical society called into existence. In 1795 MUNGO PARK was despatched by the Association to the west coast. He started from the Gambia, and after many adventures, in which he was captured by the Moors, arrived at the banks of the Niger, which he traced along its middle course, but failed to reach as far as Timbuctoo. He made a second attempt in 1805, hoping by sailing down the Niger to prove its identity with the river known at its mouth as the Congo; but he was forced to return, and died at Boussa, without having determined the remaining course of the Niger.

Attention was thus drawn to the existence of the mysterious city of Timbuctoo, of which Mungo Park had brought back curious rumours on his return from his first journey. This was visited in 1811 by a British seaman named Adams, who had been wrecked on the Moorish coast, and taken as a slave by the Moors across to Timbuctoo. He was ultimately ransomed by the British consul at Mogador, and his account revived interest in West African exploration. Attempts were made to penetrate the secret of the Niger, both from Senegambia and from the Congo, but both were failures, and a fresh method was adopted, possibly owing to Adams' experience in the attempt to reach the Niger by the caravan routes across the Sahara. In 1822 Major Denham and Lieutenant Clapperton left Murzouk, the capital of Fezzan, and made their way to Lake Chad and thence to Bornu. Clapperton, later on, again visited the Niger from Benin. Altogether these two travellers added some two thousand miles of route to our knowledge of, West Africa. In 1826-27 Timbuctoo was at last visited by two Europeans—Major Laing in the former year, who was murdered there; and a young Frenchman, Réné Caillié, in the latter. His account aroused great interest, and Tennyson began his poetic career by a prize-poem on the subject of the mysterious African capital.

It was not till 1850 that the work of Denham and Clapperton was again taken up by Barth, who for five years explored the whole country to the west of Lake Chad, visiting Timbuctoo, and connecting the lines of route of Clapperton and Caillié. What he did for the west of Lake Chad was accomplished by Nachtigall east of that lake in Darfur and Wadai, in a journey which likewise took five years (1869– 74). Of recent years political interests have caused numerous expeditions, especially by the French to connect their possessions in Algeria and Tunis with those on the Gold Coast and on the Senegal.

The next stage in African exploration is connected with the name of the man to whom can be traced practically the whole of recent discoveries. By his tact in dealing with the natives, by his calm pertinacity and dauntless courage, DAVID LIVINGSTONE succeeded in opening up the entirely unknown districts of Central Africa. Starting from the Cape in 1849, he worked his way northward to the Zambesi, and then to Lake Dilolo, and after five years' wandering reached the western coast of Africa at Loanda. Then retracing his steps to the Zambesi again, he followed its course to its mouth on the east coast, thus for the first time crossing Africa from west to east. In a second journey, on which he started in 1858, he commenced tracing the course of the river Shiré, the most important affluent of the Zambesi, and in so doing arrived on the shores of Lake Nyassa in September 1859.

Meanwhile two explorers, Captain (afterwards Sir Richard) Burton and Captain Speke, had started from Zanzibar to discover a lake of which rumours had for a long time been heard, and in the following year succeeded in reaching Lake Tanganyika. On their return Speke parted from Burton and took a route more to the north, from which he saw another great lake, which afterwards turned out to be the Victoria Nyanza. In 1860, with another companion (Captain Grant), Speke returned to the Victoria Nyanza, and traced out its course. On the north of it they found a great river trending to the north, which they followed as far as Gondokoro. Here they found Mr. (afterwards Sir Samuel) Baker, who had travelled up the White Nile to investigate its source, which they thus proved to be in the Lake Victoria Nyanza. Baker continued his search, and succeeded in showing that another source of the Nile was to be found in a smaller lake to the west, which he named Albert Nyanza. Thus these three Englishmen had combined to solve the long-sought problem of the sources of the Nile.

The discoveries of the Englishmen were soon followed up by important political action by the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, who claimed the whole course of the Nile as part of his dominions, and established stations all along it. This, of course, led to full information about the basin of the Nile being acquired for geographical purposes, and, under Sir Samuel Baker and Colonel Gordon, civilisation was for a time in possession of the Nile from its source to its mouth.

Meanwhile Livingstone had set himself to solve the problem of the great Lake Tanganyika, and started on his last journey in 1865 for that purpose. He discovered Lakes Moero and Bangweolo, and the river Nyangoue, also known as Lualaba. So much interest had been aroused by Livingstone's previous exploits of discovery, that when nothing had been heard of him for some time, in 1869 Mr. H. M. Stanley was sent by the proprietors of the New York Herald, for whom he had previously acted as war-correspondent, to find Livingstone. He started in 1871 from Zanzibar, and before the end of the year had come across a white man in the heart of the Dark Continent, and greeted him with the historic query, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Two years later Livingstone died, a martyr to geographical and missionary enthusiasm. His work was taken up by Mr. Stanley, who in 1876 was again despatched to continue Livingstone's work, and succeeded in crossing the Dark Continent from Zanzibar to the mouth of the Congo, the whole course of which he traced, proving that the Lualaba or Nyangoue were merely different names or affluents of this mighty stream. Stanley's remarkable journey completed the rough outline of African geography by defining the course of the fourth great river of the continent.

But Stanley's journey across the Dark Continent was destined to be the starting-point of an entirely new development of the African problem. Even while Stanley was on his journey a conference had been assembled at Brussels by King Leopold, in which an international committee was formed representing all the nations of Europe, nominally for the exploration of Africa, but, as it turned out, really for its partition among the European powers. Within fifteen years of the assembly of the conference the interior of Africa had been parcelled out, mainly among the five powers, England, France, Germany, Portugal, and Belgium. As in the case of America, geographical discovery was soon followed by political division.

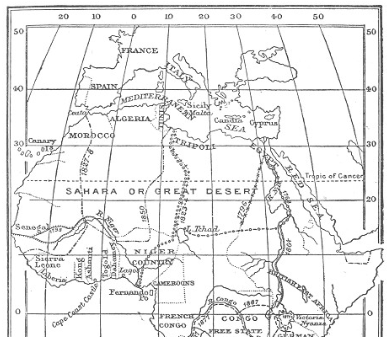

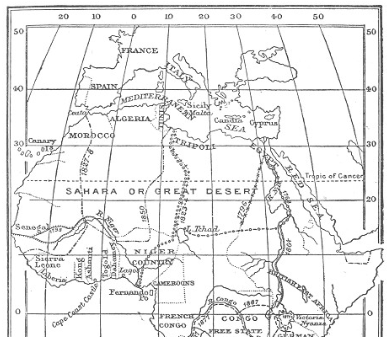

EXPLORATION AND PARTITION OF AFRICA.

The process began by the carving out of a state covering the whole of the newly-discovered Congo, nominally independent, but really forming a colony of Belgium, King Leopold supplying the funds for that purpose. Mr. Stanley was despatched in 1879 to establish stations along the lower course of the river, but, to his surprise, he found that he had been anticipated by M. de Brazza, a Portuguese in the service of France, who had been despatched on a secret mission to anticipate the King of the Belgians in seizing the important river mouth. At the same time Portugal put in claims for possession of the Congo mouth, and it became clear that international rivalries would interfere with the foundation of any state on the Congo unless some definite international arrangement was arrived at. Almost about the same time, in 1880, Germany began to enter the field as a colonising power in Africa. In South-West Africa and in the Cameroons, and somewhat later in Zanzibar, claims were set up on behalf of Germany by Prince Bismarck which conflicted with English interests in those districts, and under his presidency a Congress was held at Berlin in the winter of 1884-85 to determine the rules of the claims by which Africa could be partitioned. The old historic claims of Portugal to the coast of Africa, on which she had established stations both on the west and eastern side, were swept away by the principle that only effective occupation could furnish a claim of sovereignty. This great principle will rule henceforth the whole course of African history; in other words, the good old Border rule

"That they should take who have the power.

And they should keep who can."

Almost immediately after the sitting of the Berlin Congress, and indeed during it, arrangements were come to by which the respective claims of England and Germany in South-West Africa were definitely determined. Almost immediately afterwards a similar process had to be gone through in order to determine the limits of the respective "spheres of influence," as they began to be called, of Germany and England in East Africa. A Chartered Company, called the British East Africa Association, was to administer the land north of Victoria Nyanza bounded on the west by the Congo Free State, while to the north it extended till it touched the revolted provinces of Egypt, of which we shall soon speak. In South Africa a similar Chartered Company, under the influence of Mr. Cecil Rhodes, practically controlled the whole country from Cape Colony up to German East Africa and the Congo Free State.

The winter of 1890-91 was especially productive of agreements of demarcation. After a considerable amount of friction owing to the encroachments of Major Serpa Pinto, the limits of Portuguese Angola on the west coast were then determined, being bounded on the east by the Congo Free State and British Central Africa; and at the same time Portuguese East Africa was settled in its relation both to British Central Africa on the west and German East Africa on the north. Meanwhile Italy had put in its claims for a share in the spoil, and the eastern horn of Africa, together with Abyssinia, fell to its share, though it soon had to drop it, owing to the unexpected vitality shown by the Abyssinians. In the same year (1890) agreements between Germany and England settled the line of demarcation between the Cameroons and Togoland, with the adjoining British territories; while in August of the same year an attempt was made to limit the abnormal pretensions of the French along the Niger, and as far as Lake Chad. Here the British interests were represented by another Chartered Company, the Royal Niger Company. Unfortunately the delimitation was not very definite, not being by river courses or meridians as in other cases, but merely by territories ruled over by native chiefs, whose boundaries were not then particularly distinct. This has led to considerable friction, lasting even up to the present day; and it is only with reference to the demarcation between England and France in Africa that any doubt still remains with regard to the western and central portions of the continent.

Towards the north-east the problem of delimitation had been complicated by political events, which ultimately led to another great exploring expedition by Mr. Stanley. The extension of Egypt into the Equatorial Provinces under Ismail Pasha, due in large measure to the geographical discoveries of Grant, Speke, and Baker, led to an enormous accumulation of debt, which caused the country to become bankrupt, Ismail Pasha to be deposed, and Egypt to be administered jointly by France and England on behalf of the European bondholders. This caused much dissatisfaction on the part of the Egyptian officials and army officers, who were displaced by French and English officials; and a rebellion broke out under Arabi Pasha. This led to the armed intervention of England, France having refused to co-operate, and Egypt was occupied by British troops. The Soudan and Equatorial Provinces had independently revolted under Mohammedan fanaticism, and it was determined to relinquish those Egyptian possessions, which had originally led to bankruptcy. General Gordon was despatched to relieve the various Egyptian garrisons in the south, but being without support, ultimately failed, and was killed in 1885. One of Gordon's lieutenants, a German named Schnitzler, who appears to have adopted Mohammedanism, and was known as Emin Pasha, was thus isolated in the midst of Africa near the Albert Nyanza, and Mr. Stanley was commissioned to attempt his rescue in 1887. He started to march through the Congo State, and succeeded in traversing a huge tract of forest country inhabited by diminutive savages, who probably represented the Pigmies of the ancients. He succeeded in reaching Emin Pasha, and after much persuasion induced him to accompany him to Zanzibar, only, however, to return as a German agent to the Albert Nyanza. Mr. Stanley's journey on this occasion was not without its political aspects, since he made arrangements during the eastern part of his journey for securing British influence for the lands afterwards handed over to the British East Africa Company.

All these political delimitations were naturally accompanied by explorations, partly scientific, but mainly political. Major Serpa Pinto twice crossed Africa in an attempt to connect the Portuguese settlements on the two coasts. Similarly, Lieutenant Wissmann also crossed Africa twice, between 1881 and 1887, in the interests of the Congo State, though he ultimately became an official of his native country, Germany. Captain Lugard had investigated the region between the three Lakes Nyanza, and secured it for Great Britain. In South Africa British claims were successfully and successively advanced to Bechuana-land, Mashona-land, and Matabele-land, and, under the leadership of Mr. Cecil Rhodes, a railway and telegraph were rapidly pushed forward towards the north. Owing to the enterprise of Mr. (now Sir H. H.) Johnstone, the British possessions were in 1891 pushed up as far as Nyassa-land. By that date, as we have seen, various treaties with Germany and Portugal had definitely fixed the contour lines of the different possessions of the three countries in South Africa. By 1891 the interior of Africa, which had up to 1880 been practically a blank, could be mapped out almost with as much accuracy as, at any rate, South America. Europe had taken possession of Africa.

One of the chief results of this, and formally one of its main motives, was the abolition of the slave trade. North Africa has been Mohammedan since the eighth century, and Islam has always recognised slavery, consequently the Arabs of the north have continued to make raids upon the negroes of Central Africa, to supply the Mohammedan countries of West Asia and North Africa with slaves. The Mahdist rebellion was in part at least a reaction against the abolition of slavery by Egypt, and the interest of the next few years will consist in the last stand of the slave merchants in the Soudan, in Darfur, and in Wadai, east of Lake Chad, where the only powerful independent Mohammedan Sultanate still exists. England is closely pressing upon the revolted provinces, along the upper course of the Nile; while France is attempting, by expeditions from the French Congo and through Abyssinia, to take possession of the Upper Nile before England conquers it. The race for the Upper Nile is at present one of the sources of danger of European war.

While exploration and conquest have either gone hand in hand, or succeeded one another very closely, there has been a third motive that has often led to interesting discoveries, to be followed by annexation. The mighty hunters of Africa have often brought back, not alone ivory and skins, but also interesting information of the interior. The gorgeous narratives of Gordon Cumming in the "fifties" were one of the causes which led to an interest in African exploration. Many a lad has had his imagination fired and his career determined by the exploits of Gordon Cumming, which are now, however, almost forgotten. Mr. F. C. Selous has in our time surpassed even Gordon Cumming's exploits, and has besides done excellent work as guide for the successive expeditions into South Africa.

Thus, practically within our own time, the interior of Africa, where once geographers, as the poet Butler puts it, "placed elephants instead of towns," has become known, in its main outlines, by successive series of intrepid explorers, who have often had to be warriors as well as scientific men. Whatever the motives that have led the white man into the centre of the Dark Continent—love of adventure, scientific curiosity, big game, or patriotism—the result has been that the continent has become known instead of merely its coast-line. On the whole, English exploration has been the main means by which our knowledge of the interior of Africa has been obtained, and England has been richly rewarded by coming into possession of the most promising parts of the continent—the Nile valley and temperate South Africa. But France has also gained a huge extent of country covering almost the whole of North-West Africa. While much of this is merely desert, there are caravan routes which tap the basin of the Niger and conduct its products to Algeria, conquered by France early in the century, and to Tunis, more recently appropriated. The West African provinces of France have, at any rate, this advantage, that they are nearer to the mother-country than any other colony of a European power; and the result may be that African soldiers may one of these days fight for France on European soil, just as the Indian soldiers were imported to Cyprus by Lord Beaconsfield in 1876. Meanwhile, the result of all this international ambition has been that Africa in its entirety is now known and accessible to European civilisation.

[Authorities: Kiepert, Beiträgge zur Entdeckungsgeschichte Afrikas, 1873; Brown, The Story of Africa, 4 vols., 1894; Scott Keltie, The Partition of Africa, 1896.]