CHAPTER I

THE WORLD AS KNOWN TO THE ANCIENTS

Before telling how the ancients got to know that part of the world with which they finally became acquainted when the Roman Empire was at its greatest extent, it is as well to get some idea of the successive stages of their knowledge, leaving for the next chapter the story of how that knowledge was obtained. As in most branches of organised knowledge, it is to the Greeks that we owe our acquaintance with ancient views of this subject. In the early stages they possibly learned something from the Phœnicians, who were the great traders and sailors of antiquity, and who coasted along the Mediterranean, ventured through the Straits of Gibraltar, and traded with the British Isles, which they visited for the tin found in Cornwall. It is even said that one of their admirals, at the command of Necho, king of Egypt, circumnavigated Africa, for Herodotus reports that on the homeward voyage the sun set in the sea on the right hand. But the Phœnicians kept their geographical knowledge to themselves as a trade secret, and the Greeks learned but little from them.

The first glimpse that we have of the notions which the Greeks possessed of the shape and the inhabitants of the earth is afforded by the poems passing under the name of HOMER. These poems show an intimate knowledge of Northern Greece and of the western coasts of Asia Minor, some acquaintance with Egypt, Cyprus, and Sicily; but all the rest, even of the Eastern Mediterranean, is only vaguely conceived by their author. Where he does not know he imagines, and some of his imaginings have had a most important influence upon the progress of geographical knowledge. Thus he conceives of the world as being a sort of flat shield, with an extremely wide river surrounding it, known as Ocean. The centre of this shield was at Delphi, which was regarded as the "navel" of the inhabited world. According to Hesiod, who is but little later than Homer, up in the far north were placed a people known as the Hyperboreani, or those who dwelt at the back of the north wind; whilst a corresponding place in the south was taken by the Abyssinians. All these four conceptions had an important influence upon the views that men had of the world up to times comparatively recent. Homer also mentioned the pigmies as living in Africa. These were regarded as fabulous, till they were re- discovered by Dr. Schweinfurth and Mr. Stanley in our own time.

It is probably from the Babylonians that the Greeks obtained the idea of an all-encircling ocean. Inhabitants of Mesopotamia would find themselves reaching the ocean in almost any direction in which they travelled, either the Caspian, the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, or the Persian Gulf. Accordingly, the oldest map of the world which has been found is one accompanying a cuneiform inscription, and representing the plain of Mesopotamia with the Euphrates flowing through it, and the whole surrounded by two concentric circles, which are named briny waters. Outside these, however, are seven detached islets, possibly representing the seven zones or climates into which the world was divided according to the ideas of the Babylonians, though afterwards they resorted to the ordinary four cardinal points. What was roughly true of Babylonia did not in any way answer to the geographical position of Greece, and it is therefore probable that in the first place they obtained their ideas of the surrounding ocean from the Babylonians.

THE EARLIEST MAP OF THE WORLD

It was after the period of Homer and Hesiod that the first great expansion of Greek knowledge about the world began, through the extensive colonisation which was carried on by the Greeks around the Eastern Mediterranean. Even to this day the natives of the southern part of Italy speak a Greek dialect, owing to the wide extent of Greek colonies in that country, which used to be called "Magna Grecia," or "Great Greece." Marseilles also one of the Greek colonies (600 B.C.), which, in its turn, sent out other colonies along the Gulf of Lyons. In the East, too, Greek cities were dotted along the coast of the Black Sea, one of which, Byzantium, was destined to be of world-historic importance. So, too, in North Africa, and among the islands of the Ægean Sea, the Greeks colonised throughout the sixth and fifth centuries B.C., and in almost every case communication was kept up between the colonies and the mother-country.

Now, the one quality which has made the Greeks so distinguished in the world's history was their curiosity; and it was natural that they should desire to know, and to put on record, the large amount of information brought to the mainland of Greece from the innumerable Greek colonies. But to record geographical knowledge, the first thing that is necessary is a map, and accordingly it is a Greek philosopher named ANAXIMANDER of Miletus, of the sixth century B.C., to whom we owe the invention of map-drawing. Now, in order to make a map of one's own country, little astronomical knowledge is required. As we have seen, savages are able to draw such maps; but when it comes to describing the relative positions of countries divided from one another by seas, the problem is not so easy. An Athenian would know roughly that Byzantium (now called Constantinople) was somewhat to the east and to the north of him, because in sailing thither he would have to sail towards the rising sun, and would find the climate getting colder as he approached Byzantium. So, too, he might roughly guess that Marseilles was somewhere to the west and north of him; but how was he to fix the relative position of Marseilles and Byzantium to one another? Was Marseilles more northerly than Byzantium? Was it very far away from that city? For though it took longer to get to Marseilles, the voyage was winding, and might possibly bring the vessel comparatively near to Byzantium, though there might be no direct road between the two cities. There was one rough way of determining how far north a place stood: the very slightest observation of the starry heavens would show a traveller that as he moved towards the north, the pole-star rose higher up in the heavens. How much higher, could be determined by the angle formed by a stick pointing to the pole-star, in relation to one held horizontally. If, instead of two sticks, we cut out a piece of metal or wood to fill up the enclosed angle, we get the earliest form of the sun-dial, known as the gnomon, and according to the shape of the gnomon the latitude of a place is determined. Accordingly, it is not surprising to find that the invention of the gnomon is also attributed to Anaximander, for without some such instrument it would have been impossible for him to have made any map worthy of the name. But it is probable that Anaximander did not so much invent as introduce the gnomon, and, indeed, Herodotus, expressly states that this instrument was derived from the Babylonians, who were the earliest astronomers, so far as we know. A curious point confirms this, for the measurement of angles is by degrees, and degrees are divided into sixty seconds, just as minutes are. Now this division into sixty is certainly derived from Babylonia in the case of time measurement, and is therefore of the same origin as regards the measurement of angles.

We have no longer any copy of this first map of the world drawn up by Anaximander, but there is little doubt that it formed the foundation of a similar map drawn by a fellow-townsman of Anaximander, HECATÆUS of Miletus, who seems to have written the first formal geography. Only fragments of this are extant, but from them we are able to see that it was of the nature of a periplus, or seaman's guide, telling how many days' sail it was from one point to another, and in what direction. We know also that he arranged his whole subject into two books, dealing respectively with Europe and Asia, under which latter term he included part of what we now know as Africa. From the fragments scholars have been able to reproduce the rough outlines of the map of the world as it presented itself to Hecatæus. From this it can be seen that the Homeric conception of the surrounding ocean formed a chief determining feature in Hecatæus's map. For the rest, he was acquainted with the Mediterranean, Red, and Black Seas, and with the great rivers Danube, Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, and Indus.

The next great name in the history of Greek geography is that of HERODOTUS of Halicarnassus, who might indeed be equally well called the Father of Geography as the Father of History. He travelled much in Egypt, Babylonia, Persia, and on the shores of the Black Sea, while he was acquainted with Greece, and passed the latter years of his life in South Italy. On all these countries he gave his fellow-citizens accurate and tolerably full information, and he had diligently collected knowledge about countries in their neighbourhood. In particular he gives full details of Scythia (or Southern Russia), and of the satrapies and royal roads of Persia. As a rule, his information is as accurate as could be expected at such an early date, and he rarely tells marvellous stories, or if he does, he points out himself their untrustworthiness. Almost the only traveller's yarn which Herodotus reports without due scepticism is that of the ants of India that were bigger than foxes and burrowed out gold dust for their ant-hills.

One of the stories he relates is of interest, as seeming to show an anticipation of one of Mr. Stanley's journeys. Five young men of the Nasamonians started from Southern Libya, W. of the Soudan, and journeyed for many days west till they came to a grove of trees, when they were seized by a number of men of very small stature, and conducted through marshes to a great city of black men of the same size, through which a large river flowed. This Herodotus identifies with the Nile, but, from the indication of the journey given by him, it would seem more probable that it was the Niger, and that the Nasamonians had visited Timbuctoo! Owing to this statement of Herodotus, it was for long thought that the Upper Nile flowed east and west.

After Herodotus, the date of whose history may be fixed at the easily remembered number of 444 B.C., a large increase of knowledge was obtained of the western part of Asia by the two expeditions of Xenophon and of Alexander, which brought the familiar knowledge of the Greeks as far as India. But besides these military expeditions we have still extant several log-books of mariners, which might have added considerably to Greek geography. One of these tells the tale of an expedition of the Carthaginian admiral named Hanno, down the western coast of Africa, as far as Sierra Leone, a voyage which was not afterwards undertaken for sixteen hundred years. Hanno brought back from this voyage hairy skins, which, he stated, belonged to men and women whom he had captured, and who were known to the natives by the name of Gorillas. Another log-book is that of a Greek named Scylax, who gives the sailing distances between nearly all ports on the Mediterranean and Black Seas, and the number of days required to pass from one to another. From this it would seem that a Greek merchant vessel could manage on the average fifty miles a day. Besides this, one of Alexander's admirals, named Nearchus, learned to carry his ships from the mouth of the Indus to the Arabian Gulf. Later on, a Greek sailor, Hippalus, found out that by using the monsoons at the appropriate times, he could sail direct from Arabia to India without laboriously coasting along the shores of Persia and Beluchistan, and in consequence the Greeks gave his name to the monsoon. For information about India itself, the Greeks were, for a long time, dependent upon the account of Megasthenes, an ambassador sent by Seleucus, one of Alexander's generals, to the Indian king of the Punjab.

While knowledge was thus gained of the East, additional information was obtained about the north of Europe by the travels of one PYTHEAS, a native of Marseilles, who flourished about the time of Alexander the Great (333 B.C.), and he is especially interesting to us as having been the first civilised person who can be identified as having visited Britain. He seems to have coasted along the Bay of Biscay, to have spent some time in England,—which he reckoned as 40,000 stadia (4000 miles) in circumference,—and he appears also to have coasted along Belgium and Holland, as far as the mouth of the Elbe. Pytheas is, however, chiefly known in the history of geography as having referred to the island of Thule, which he described as the most northerly point of the inhabited earth, beyond which the sea became thickened, and of a jelly-like consistency. He does not profess to have visited Thule, and his account probably refers to the existence of drift ice near the Shetlands.

All this new information was gathered together, and made accessible to the Greek reading world, by ERATOSTHENES, librarian of Alexandria (240-196 B.C.), who was practically the founder of scientific geography. He was the first to attempt any accurate measurement of the size of the earth, and of its inhabited portion. By his time the scientific men of Greece had become quite aware of the fact that the earth was a globe, though they considered that it was fixed in space at the centre of the universe. Guesses had even been made at the size of this globe, Aristotle fixing its circumference at 400,000 stadia (or 40,000 miles), but Eratosthenes attempted a more accurate measurement. He compared the length of the shadow thrown by the sun at Alexandria and at Syene, near the first cataract of the Nile, which he assumed to be on the same meridian of longitude, and to be at about 5000 stadia (500 miles) distance. From the difference in the length of the shadows he deduced that this distance represented one-fiftieth of the circumference of the earth, which would accordingly be about 250,000 stadia, or 25,000 geographical miles. As the actual circumference is 24,899 English miles, this was a very near approximation, considering the rough means Eratosthenes had at his disposal.

Having thus estimated the size of the earth, Eratosthenes then went on to determine the size of that portion which the ancients considered to be habitable. North and south of the lands known to him, Eratosthenes and all the ancients considered to be either too cold or too hot to be habitable; this portion he reckoned to extend to 38,000 stadia, or 3800 miles. In reckoning the extent of the habitable portion from east to west, Eratosthenes came to the conclusion that from the Straits of Gibraltar to the east of India was about 80,000 stadia, or, roughly speaking, one-third of the earth's surface. The remaining two-thirds were supposed to be covered by the ocean, and Eratosthenes prophetically remarked that "if it were not that the vast extent of the Atlantic Sea rendered it impossible, one might almost sail from the coast of Spain to that of India along the same parallel." Sixteen hundred years later, as we shall see, Columbus tried to carry out this idea. Eratosthenes based his calculations on two fundamental lines, corresponding in a way to our equator and meridian of Greenwich: the first stretched, according to him, from Cape St. Vincent, through the Straits of Messina and the island of Rhodes, to Issus (Gulf of Iskanderun); for his starting-line in reckoning north and south he used a meridian passing through the First Cataract, Alexandria, Rhodes, and Byzantium.

The next two hundred years after Eratosthenes' death was filled up by the spread of the Roman Empire, by the taking over by the Romans of the vast possessions previously held by Alexander and his successors and by the Carthaginians, and by their spread into Gaul, Britain, and Germany. Much of the increased knowledge thus obtained was summed up in the geographical work of STRABO, who wrote in Greek about 20 B.C. He introduced from the extra knowledge thus obtained many modifications of the system of Eratosthenes, but, on the whole, kept to his general conception of the world. He rejected, however, the existence of Thule, and thus made the world narrower; while he recognised the existence of Ierne, or Ireland; which he regarded as the most northerly part of the habitable world, lying, as he thought, north of Britain.

Between the time of Strabo and that of Ptolemy, who sums up all the knowledge of the ancients about the habitable earth, there was only one considerable addition to men's acquaintance with their neighbours, contained in a seaman's manual for the navigation of the Indian Ocean, known as the Periplus of the Erythræan Sea. This gave very full and tolerably accurate accounts of the coasts from Aden to the mouth of the Ganges, though it regarded Ceylon as much greater, and more to the south, than it really is; but it also contains an account of the more easterly parts of Asia, Indo-China, and China itself, "where the silk comes from." This had an important influence on the views of Ptolemy, as we shall see, and indirectly helped long afterwards to the discovery of America.

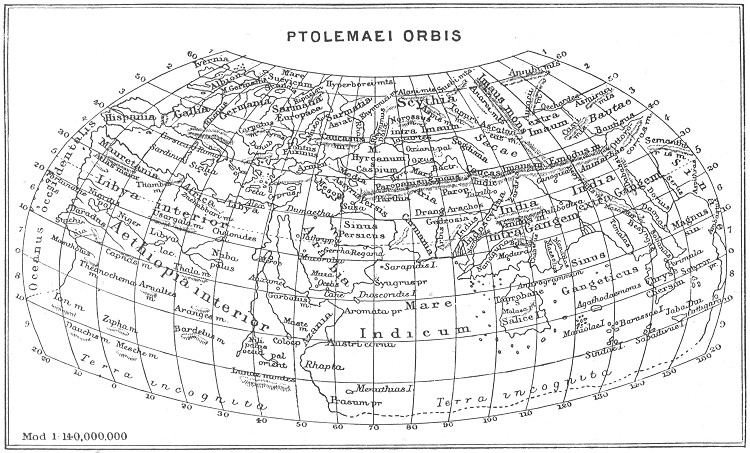

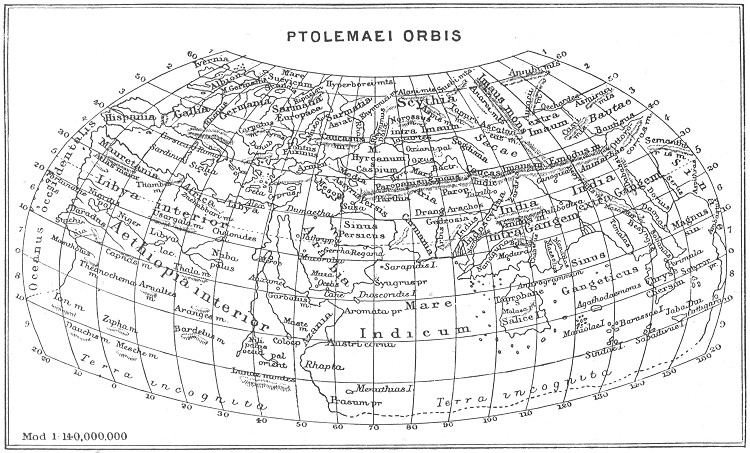

PTOLEMAEI ORBIS

It was left to PTOLEMY of Alexandria to sum up for the ancient world all the knowledge that had been accumulating from the time of Eratosthenes to his own day, which we may fix at about 150 A.D. He took all the information he could find in the writings of the preceding four hundred years, and reduced it all to one uniform scale; for it is to him that we owe the invention of the method and the names of latitude and longitude. Previous writers had been content to say that the distance between one point and another was so many stadia, but he reduced all this rough reckoning to so many degrees of latitude and longitude, from fixed lines as starting-points. But, unfortunately, all these reckonings were rough calculations, which are almost invariably beyond the truth; and Ptolemy, though the greatest of ancient astronomers, still further distorted his results by assuming that a degree was 500 stadia, or 50 geographical miles. Thus when he found in any of his authorities that the distance between one port and another was 500 stadia, he assumed, in the first place, that this was accurate, and, in the second, that the distance between the two places was equal to a degree of latitude or longitude, as the case might be. Accordingly he arrived at the result that the breadth of the habitable globe was, as he put it, twelve hours of longitude (corresponding to 180°)—nearly one-third as much again as the real dimensions from Spain to China. The consequence of this was that the distance from Spain to China westward was correspondingly diminished by sixty degrees (or nearly 4000 miles), and it was this error that ultimately encouraged Columbus to attempt his epoch-making voyage.

Ptolemy's errors of calculation would not have been so extensive but that he adopted a method of measurement which made them accumulative. If he had chosen Alexandria for the point of departure in measuring longitude, the errors he made when reckoning westward would have been counterbalanced by those reckoning eastward, and would not have resulted in any serious distortion of the truth; but instead of this, he adopted as his point of departure the Fortunatæ Insulæ, or Canary Islands, and every degree measured to the east of these was one-fifth too great, since he assumed that it was only fifty miles in length. I may mention that so great has been the influence of Ptolemy on geography, that, up to the middle of the last century, Ferro, in the Canary Islands, was still retained as the zero-point of the meridians of longitude.

Another point in which Ptolemy's system strongly influenced modern opinion was his departure from the previous assumption that the world was surrounded by the ocean, derived from Homer. Instead of Africa being thus cut through the middle by the ocean, Ptolemy assumed, possibly from vague traditional knowledge, that Africa extended an unknown length to the south, and joined on to an equally unknown continent far to the east, which, in the Latinised versions of his astronomical work, was termed "terra australis incognita," or "the unknown south land." As, by his error with regard to the breadth of the earth, Ptolemy led to Columbus; so, by his mistaken notions as to the "great south land," he prepared the way for the discoveries of Captain Cook. But notwithstanding these errors, which were due partly to the roughness of the materials which he had to deal with, and partly to scientific caution, Ptolemy's work is one of the great monuments of human industry and knowledge. For the Old World it remained the basis of all geographical knowledge up to the beginning of the last century, just as his astronomical work was only finally abolished by the work of Newton. Ptolemy has thus the rare distinction of being the greatest authority on two important departments of human knowledge—astronomy and geography—for over fifteen hundred years. Into the details of his description of the world it is unnecessary to go. The map will indicate how near he came to the main outlines of the Mediterranean, of Northwest Europe, of Arabia, and of the Black Sea. Beyond these regions he could only depend upon the rough indications and guesses of untutored merchants. But it is worth while referring to his method of determining latitude, as it was followed up by most succeeding geographers. Between the equator and the most northerly point known to him, he divides up the earth into horizontal strips, called by him "climates," and determined by the average length of the longest day in each. This is a very rough method of determining latitude, but it was probably, in most cases, all that Ptolemy had to depend upon, since the measurement of angles would be a rare accomplishment even in modern times, and would only exist among a few mathematicians and astronomers in Ptolemy's days. With him the history of geographical knowledge and discovery in the ancient world closes.

In this chapter I have roughly given the names and exploits of the Greek men of science, who summed up in a series of systematic records the knowledge obtained by merchants, by soldiers, and by travellers of the extent of the world known to the ancients. Of this knowledge, by far the largest amount was gained, not by systematic investigation for the purpose of geography, but by military expeditions for the purpose of conquest. We must now retrace our steps, and give a rough review of the various stages of conquest. We must now retrace our steps, and give a rough review of the various stages of conquest by which the different regions of the Old World became known to the Greeks and the Roman Empire, whose knowledge Ptolemy summarises.

[Authorities: Bunbury, History of Ancient Geography, 2 vols., 1879; Tozer, History of Ancient Geography, 1897.]