CHAPTER II

THE SPREAD OF CONQUEST IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

In a companion volume of this series, "The Story of Extinct Civilisations in the East," will be found an account of the rise and development of the various nations who held sway over the west of Asia at the dawn of history. Modern discoveries of remarkable interest have enabled us to learn the condition of men in Asia Minor as early as 4000 B.C. All these early civilisations existed on the banks of great rivers, which rendered the land fertile through which they passed.

We first find man conscious of himself, and putting his knowledge on record, along the banks of the great rivers Nile, Euphrates, and Tigris, Ganges and Yang-tse-Kiang. But for our purposes we are not concerned with these very early stages of history. The Egyptians got to know something of the nations that surrounded them, and so did the Assyrians. A summary of similar knowledge is contained in the list of tribes given in the tenth chapter of Genesis, which divides all mankind, as then known to the Hebrews, into descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japhet—corresponding, roughly, to Asia, Europe, and Africa. But in order to ascertain how the Romans obtained the mass of information which was summarised for them by Ptolemy in his great work, we have merely to concentrate our attention on the remarkable process of continuous expansion which ultimately led to the existence of the Roman Empire.

All early histories of kingdoms are practically of the same type. A certain tract of country is divided up among a certain number of tribes speaking a common language, and each of these tribes ruled by a separate chieftain. One of these tribes then becomes predominant over the rest, through the skill in war or diplomacy of one of its chiefs, and the whole of the tract of country is thus organised into one kingdom. Thus the history of England relates how the kingdom of Wessex grew into predominance over the whole of the country; that of France tells how the kings who ruled over the Isle of France spread their rule over the rest of the land; the history of Israel is mainly an account of how the tribe of Judah obtained the hegemony of the rest of the tribes; and Roman history, as its name implies, informs us how the inhabitants of a single city grew to be the masters of the whole known world. But their empire had been prepared for them by a long series of similar expansions, which might be described as the successive swallowing up of empire after empire, each becoming overgrown in the process, till at last the series was concluded by the Romans swallowing up the whole. It was this gradual spread of dominion which, at each stage, increased men's knowledge of surrounding nations, and it therefore comes within our province to roughly sum up these stages, as part of the story of geographical discovery.

Regarded from the point of view of geography, this spread of man's knowledge might be compared to the growth of a huge oyster-shell, and, from that point of view, we have to take the north of the Persian Gulf as the apex of the shell, and begin with the Babylonian Empire. We first have the kingdom of Babylon—which, in the early stages, might be best termed Chaldæa—in the south of Mesopotamia (or the valley between the two rivers, Tigris and Euphrates), which, during the third and second millennia before our era, spread along the valley of the Tigris. But in the fourteenth century B.C., the Assyrians to the north of it, though previously dependent upon Babylon, conquered it, and, after various vicissitudes, established themselves throughout the whole of Mesopotamia and much of the surrounding lands. In 604 B.C. the capital of this great empire was moved once more to Babylon, so that in the last stage, as well as in the first, it may be called Babylonia. For purposes of distinction, however, it will be as well to call these three successive stages Chaldæa, Assyria, and Babylonia.

Meanwhile, immediately to the east, a somewhat similar process had been gone through, though here the development was from north to south, the Medes of the north developing a powerful empire in the north of Persia, which ultimately fell into the hands of Cyrus the Great in 546 B.C. He then proceeded to conquer the kingdom of Lydia, in the northwest part of Asia Minor, which had previously inherited the dominions of the Hittites. Finally he proceeded to seize the empire of Babylonia, by his successful attack on the capital, 538 B.C. He extended his rule nearly as far as India on one side, and, as we know from the Bible, to the borders of Egypt on the other. His son Cambyses even succeeded in adding Egypt for a time to the Persian Empire. The oyster-shell of history had accordingly expanded to include almost the whole of Western Asia.

The next two centuries are taken up in universal history by the magnificent struggle of the Greeks against the Persian Empire—the most decisive conflict in all history, for it determined whether Europe or Asia should conquer the world. Hitherto the course of conquest had been from east to west, and if Xerxes' invasion had been successful, there is little doubt that the westward tendency would have continued. But the larger the tract of country which an empire covers—especially when different tribes and nations are included in it—the weaker and less organised it becomes. Within little more than a century of the death of Cyrus the Great the Greeks discovered the vulnerable point in the Persian Empire, owing to an expedition of ten thousand Greek mercenaries under Xenophon, who had been engaged by Cyrus the younger in an attempt to capture the Persian Empire from his brother. Cyrus was slain, 401 B.C., but the ten thousand, under the leadership of Xenophon, were enabled, to hold their own against all the attempts of the Persians to destroy them, and found their way back to Greece.

Meanwhile the usual process had been going on in Greece by which a country becomes consolidated. From time to time one of the tribes into which that mountainous country was divided obtained supremacy over the rest: at first the Athenians, owing to the prominent part they had taken in repelling the Persians; then the Spartans, and finally the Thebans. But on the northern frontiers a race of hardy mountaineers, the Macedonians, had consolidated their power, and, under Philip of Macedon, became masters of all Greece. Philip had learned the lesson taught by the successful retreat of the ten thousand, and, just before his death, was preparing to attack the Great King (of Persia) with all the forces which his supremacy in Greece put at his disposal. His son Alexander the Great carried out Philip's intentions. Within twelve years (334-323 B.C.) he had conquered Persia, Parthia, India (in the strict sense, i.e. the valley of the Indus), and Egypt. After his death his huge empire was divided up among his generals, but, except in the extreme east, the whole of it was administered on Greek methods. A Greek-speaking person could pass from one end to the other without difficulty, and we can understand how a knowledge of the whole tract of country between the Adriatic and the Indus could be obtained by Greek scholars. Alexander founded a large number of cities, all bearing his name, at various points of his itinerary; but of these the most important was that at the mouth of the Nile, known to this day as Alexandria. Here was the intellectual centre of the whole Hellenic world, and accordingly it was here, as we have seen, that Eratosthenes first wrote down in a systematic manner all the knowledge about the habitable earth which had been gained mainly by Alexander's conquests.

Important as was the triumphant march of Alexander through Western Asia, both in history and in geography, it cannot be said to have added so very much to geographical knowledge, for Herodotus was roughly acquainted with most of the country thus traversed, except towards the east of Persia and the north-west of India. But the itineraries of Alexander and his generals must have contributed more exact knowledge of the distances between the various important centres of population, and enabled Eratosthenes and his successors to give them a definite position on their maps of the world. What they chiefly learned from Alexander and his immediate successors was a more accurate knowledge of North-West India. Even as late as Strabo, the sole knowledge possessed at Alexandria of Indian places was that given by Megasthenes, the ambassador to India in the third century B.C.

Meanwhile, in the western portion of the civilised world a similar process had gone on. In the Italian peninsula the usual struggle had gone on between the various tribes inhabiting it. The fertile plain of Lombardy was not in those days regarded as belonging to Italy, but was known as Cisalpine Gaul. The south of Italy, as we have seen, was mainly inhabited by Greek colonists, and was called Great Greece. Between these tracts of country the Italian territory was inhabited by three sets of federate tribes—the Etrurians, the Samnites, and the Latins. During the 230 years between 510 B.C. and 280 B.C. Rome was occupied in obtaining the supremacy among these three sets of tribes, and by the latter date may be regarded as having consolidated Central Italy into an Italian federation, centralised at Rome. At the latter date, the Greek king Pyrrhus of Epirus, attempted to arouse the Greek colonies in Southern Italy against the growing power of Rome; but his interference only resulted in extending the Roman dominion down to the heel and big toe of Italy.

If Rome was to advance farther, Sicily would be the next step, and just at that moment Sicily was being threatened by the other great power of the West—Carthage. Carthage was the most important of the colonies founded by the Phœnicians (probably in the ninth century B.C.), and pursued in the Western Mediterranean the policy of establishing trading stations along the coast, which had distinguished the Phœnicians from their first appearance in history. They seized all the islands in that division of the sea, or at any rate prevented any other nation from settling in Corsica, Sardinia, and the Balearic Isles. In particular Carthage took possession of the western part of Sicily, which had been settled by sister Phœnician colonies. While Rome did everything in its power to consolidate its conquests by admitting the other Italians to some share in the central government, Carthage only regarded its foreign possessions as so many openings for trade. In fact, it dealt with the western littoral of the Mediterranean something like the East India Company treated the coast of Hindostan: it established factories at convenient spots. But just as the East India Company found it necessary to conquer the neighbouring territory in order to secure peaceful trade, so Carthage extended its conquests all down the western coast of Africa and the south-east part of Spain, while Rome was extending into Italy. To continue our conchological analogy, by the time of the first Punic War Rome and Carthage had each expanded into a shell, and between the two intervened the eastern section of the island of Sicily. As the result of this, Rome became master of Sicily, and then the final struggle took place with Hannibal in the second Punic War, which resulted in Rome becoming possessed of Spain and Carthage. By the year 200 B.C. Rome was practically master of the Western Mediterranean, though it took another century to consolidate its heritage from Carthage in Spain and Mauritania. During that century—the second before our era—Rome also extended its Italian boundaries to the Alps by the conquest of Cisalpine Gaul, which, however, was considered outside Italy, from which it was separated by the river Rubicon. In that same century the Romans had begun to interfere in the affairs of Greece, which easily fell into their hands, and thus prepared the way for their inheritance of Alexander's empire.

This, in the main, was the work of the first century before our era, when the expansion of Rome became practically concluded. This was mainly the work of two men, Cæsar and Pompey. Following the example of his uncle, Marius, Cæsar extended the Roman dominions beyond the Alps to Gaul, Western Germany, and Britain; but from our present standpoint it was Pompey who prepared the way for Rome to carry on the succession of empire in the more civilised portions of the world, and thereby merited his title of "Great." He pounded up, as it were, the various states into which Asia Minor was divided, and thus prepared the way for Roman dominion over Western Asia and Egypt. By the time of Ptolemy the empire was thoroughly consolidated, and his map and geographical notices are only tolerably accurate within the confines of the empire.

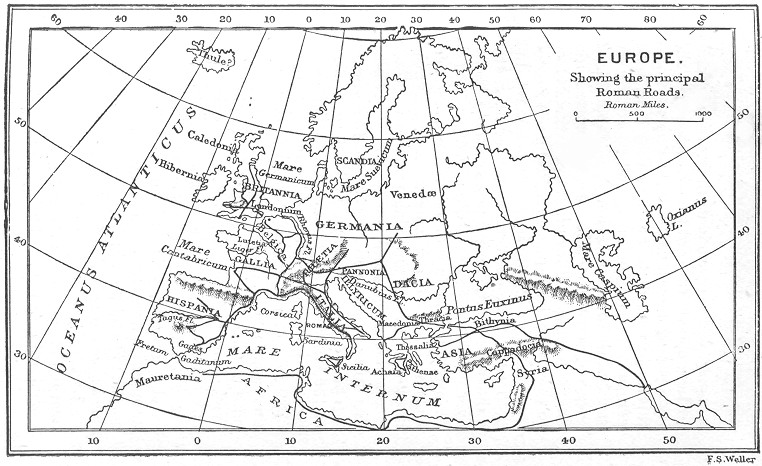

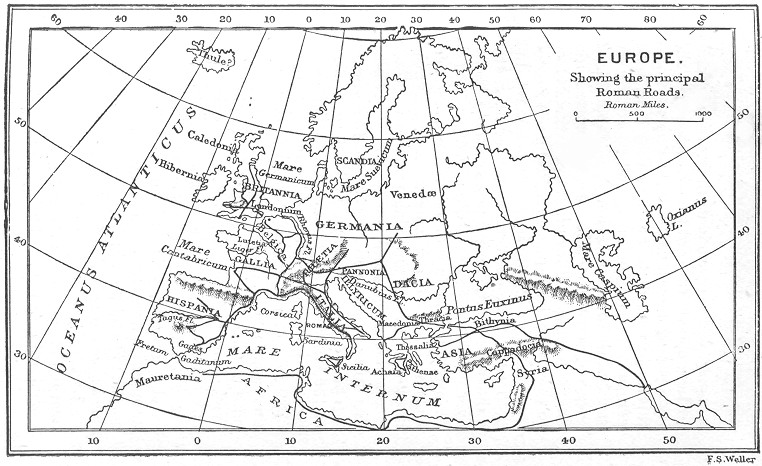

EUROPE. Showing the principal Roman Roads.

One of the means by which the Romans were enabled to consolidate their dominion must be here shortly referred to. In order that their legions might easily pass from one portion of this huge empire to another, they built roads, generally in straight lines, and so solidly constructed that in many places throughout Europe they can be traced even to the present day, after the lapse of fifteen hundred years. Owing to them, in a large measure, Rome was enabled to preserve its empire intact for nearly five hundred years, and even to this day one can trace a difference in the civilisation of those countries over which Rome once ruled, except where the devastating influence of Islam has passed like a sponge over the old Roman provinces. Civilisation, or the art of living together in society, is practically the result of Roman law, and this sense all roads in history lead to Rome.

The work of Claudius Ptolemy sums up to us the knowledge that the Romans had gained by their inheritance, on the western side, of the Carthaginian empire, and, on the eastern, of the remains of Alexander's empire, to which must be added the conquests of Cæsar in North-West Europe. Cæsar is, indeed, the connecting link between the two shells that had been growing throughout ancient history. He added Gaul, Germany, and Britain to geographical knowledge, and, by his struggle with Pompey, connected the Levant with his northerly conquests. One result of his imperial work must be here referred to. By bringing all civilised men under one rule, he prepared them for the worship of one God. This was not without its influence on travel and geographical discovery, for the great barrier between mankind had always been the difference of religion, and Rome, by breaking down the exclusiveness of local religions, and substituting for them a general worship of the majesty of the Emperor, enabled all the inhabitants of this vast empire to feel a certain communion with one another, which ultimately, as we know, took on a religious form.

The Roman Empire will henceforth form the centre from which to regard any additions to geographical knowledge. As we shall see, part of the knowledge acquired by the Romans was lost in the Dark Ages succeeding the break-up of the empire; but for our purposes this may be neglected and geographical discovery in the succeeding chapters may be roughly taken to be additions and corrections of the knowledge summed up by Claudius Ptolemy.