CHAPTER IX

THE EARLIER CAREER OF DANA

His Life at Brook Farm and His Tribune Experience.—His Break with Greeley, His Civil War Services and His Chicago Disappointment.—His Purchase of “The Sun.”

DAY and Dana each did a great thing for the Sun and incidentally for journalism and for America. Day made humanity more intelligent by making newspapers popular. Dana made newspapers more intelligent by making them human.

Day started the Sun at twenty-three and left it at twenty-eight. Dana took the Sun at forty-eight and kept it for thirty years. Each, in his time, was absolute master of the paper.

“The great idea of Day’s time,” wrote E. P. Mitchell on the Sun’s fiftieth birthday, fifteen years after Dana took hold, “was cheapness to the buyer. The great idea of the Sun as it is, was and is interest to the reader.”

Of the nine men who have been owners of the Sun, seven were of down-east Yankee stock, and six of the seven were born in New England. Of the editors-in-chief of the Sun—except in that brief period of the lease by the religious coterie—all have been New Englanders but one, and he was the son of a New Englander.

Dana was born in Hinsdale, New Hampshire, on August 8, 1819. His father was Anderson Dana, sixth in descent from Richard Dana, the colonial settler; and his mother, Ann Denison, came of straight Yankee stock. The father failed in business at Hinsdale when Charles was a child, and the family moved to Gaines, a village in western New York, where Anderson Dana became a farmer. Here the mother died, leaving four children—Charles Anderson, aged nine; Junius, seven; Maria, three, and David, an infant. The widower went to the home of Mrs. Dana’s parents near Guildhall, Vermont, and there the children were divided among relatives. Charles was sent to live with his uncle, David Denison, on a farm in the Connecticut River Valley.

There was a good teacher at the school near by, and at the age of ten Charles was considered as proficient in his English studies as many boys of fifteen. When he was twelve he had added some Latin to the three R’s. In the judgment of that day he was fit to go to work. His uncle, William Dana, was part owner of the general store of Staats & Dana, in Buffalo, New York, whither the boy was sent by stage-coach. He made himself handy in the store and lived at his uncle’s house.

Buffalo, a distributing place for freight sent West on the Erie Canal, had a population of only fifteen thousand in 1831. Many of Staats & Dana’s customers were Indians, and young Charles added to the store’s efficiency by learning the Seneca language. At night he continued his pursuit of Latin, tackled Greek, read what volumes of Tom Paine he could buy at a book-shop next door, and followed the career, military and political, of the strenuous Andrew Jackson. When he had a day off he went fishing in the Niagara River or visited the Indian reservation.

He was a normal, healthy lad, even if he knew more Latin than he should. When war threatened with Great Britain over the Caroline affair, Dana joined the City Guard and had a brief ambition to be a soldier. He was of slender build, but strong. He belonged to the Coffee Club, a literary organization, and he made a talk to it on early English poetry.

“The best days of my life,” he called this period.

Staats & Dana failed in the panic of 1837, and Charles, then eighteen, and the possessor of two hundred dollars saved from his wages, decided to go to Harvard. He left Buffalo in June, 1839, although his father did not like the idea of letting him go to Harvard.

“I know it ranks high as a literary institution, but the influence it exerts in a religious way is most horrible—even worse than Universalism.”

Anderson Dana had a horror of Unitarianism, and had heard that Charles was attending Unitarian meetings.

“Ponder well the paths of thy feet,” he wrote in solemn warning to his perilously venturesome son, “lest they lead down to the very gates of hell.”

Dana entered college without difficulty, and devoted much of his time to philosophy and general literature. He wrote to his friend, Dr. Austin Flint, whom he had met in Buffalo, and who had advised him to go to Harvard.

I am in the focus of what Professor Felton calls “supersublimated transcendentalism,” and to tell the truth, I take to it rather kindly, though I stumble sadly at some notions.

This was not strange, for besides hearing Unitarian discourse, young Dana was attending Emerson’s lectures at Harvard and reading Carlyle.

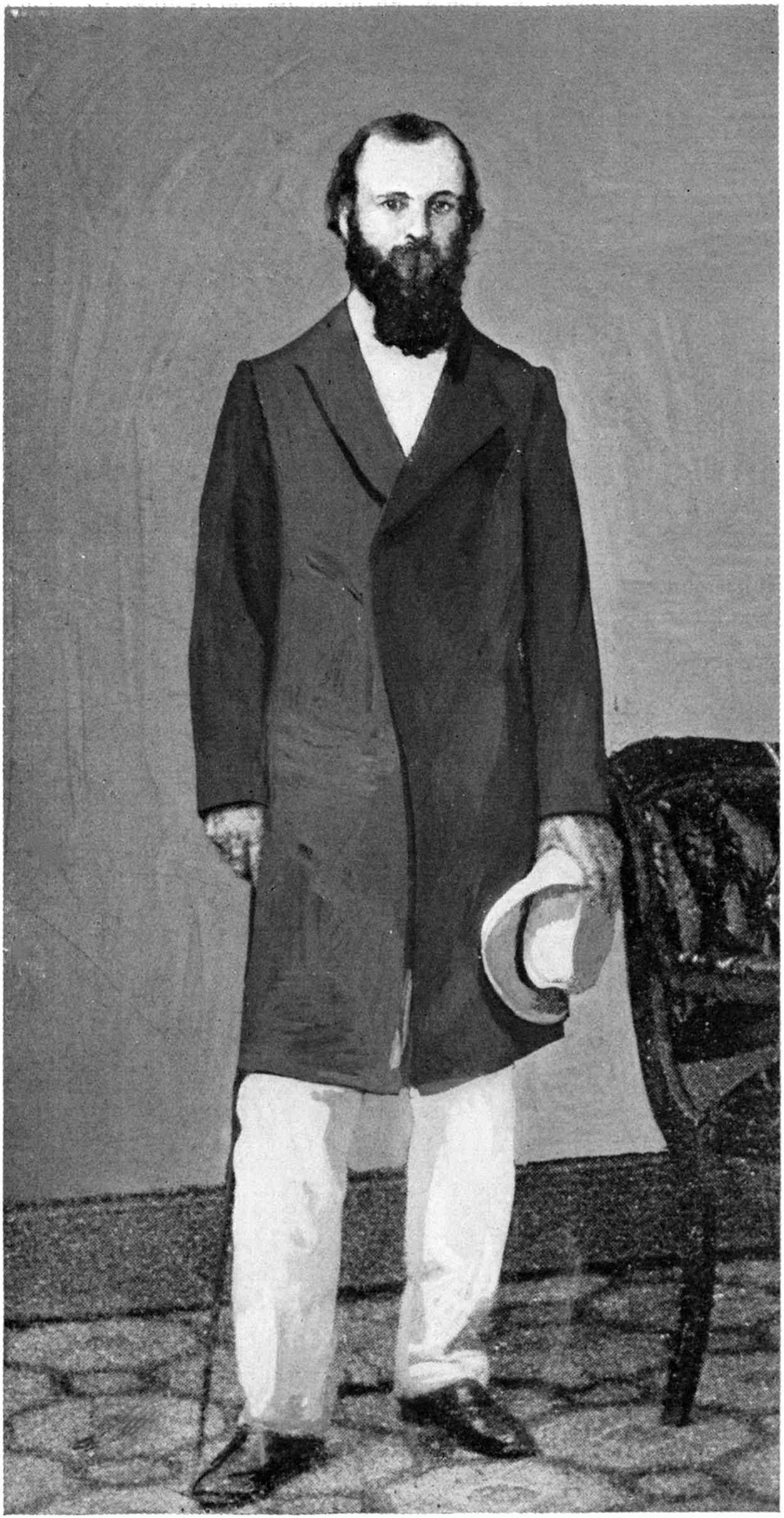

CHARLES A. DANA AT THIRTY-EIGHT

A Photograph Taken in 1857 When He Was Managing Editor of the New York “Tribune.”

In his first term Dana stood seventh in a class of seventy-four. In the spring of 1840 he left Cambridge, but pursued the university studies at the home of his uncle in Guildhall, Vermont. Here, at an expense of about a dollar a week, he put in eight hours a day at his books, and for diversion went shooting or tinkered in the farm shop. His sister, then fifteen years old, was there, and he helped her with her studies.

Dana returned to Harvard in the autumn, but not for long. His purse was about empty, and he found no means of replenishing it at Cambridge. In November the faculty gave him permission to be absent during the winter to “keep school.” Dana went to teach at Scituate, Massachusetts, getting twenty-five dollars a month and his board.

His regret at leaving college was keen, for it meant that he would miss Richard Henry Dana’s lectures on poetry, and George Ripley’s on foreign literature.

Young Dana’s mind was full in those days. There was the eager desire for education, with poverty in the path. He thought he saw a way around by going to Germany, where he could live cheaply at a university and be paid for teaching English. There was also a religious struggle.

I feel now an inclination to orthodoxy, and am trying to believe the real doctrine of the Trinity. Whether I shall settle down in Episcopacy, Swedenborgianism, or Goethean indifference to all religion, I know not. My only prayer is, “God help me!”

But the immediate reality was teaching school in a little town where most of the pupils were unruly sailors, and Dana faced it with good-natured philosophy. At the end of a day’s struggle to train some sixty or seventy Scituate youths, he went back to the home of Captain Webb, with whose family he boarded, and read Coleridge for literary quality, Swedenborg for religion, and “Oliver Twist” for diversion. Candles and whale-oil lamps were the only illuminants, and Dana’s eyes, never too strong, began to weaken.

He returned to college in the spring of 1841, but his eyes would stand no more. He was about to find work as an agricultural labourer when Brook Farm attracted him. Through George Ripley he was admitted to that association, which sought to combine labour and intellect in a beautiful communistic scheme. He agreed to teach Greek and German and to help with the farm work.

Dana subscribed for three of the thirty shares—at five hundred dollars a share—of the stock of the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and Education, as the company was legally titled. Brook Farm was a fine place of a hundred and ninety-two acres, in the town of Roxbury, about nine miles from Boston. It cost $10,500 and, as most of the shareholders had no money to pay on their stock, mortgages amounting to eleven thousand dollars were immediately clapped on the place—a feat rare in the business world, at once to mortgage a place for more than its cost. Dana, now twenty-three years old, was elected recording secretary, one of the three trustees, and a member of the committees on finance and education.

He remained as a Brook Farmer to the end of the five years that the experiment lasted. There he met Hawthorne, who lingered long enough to get much of the material for his “Blithedale Romance”; Thoreau, who had not yet gone to Walden Pond; William Ellery Channing, second, the author and journalist; Albert Brisbane, the most radical of the group of socialists of his day; and Margaret Fuller, who believed in Brook Farm, but did not live there.

Brook Farm was the perfect democracy. The members did all the work, menial and otherwise, and if there was honour it fell to him whose task was humblest. The community paid each worker a dollar a day, and charged him or her about two dollars and fifty cents a week for board. It sold its surplus produce, and it educated children at low rates. George Ripley, the Unitarian minister, was chief of the cow-milking group, and Dana helped him. Dana, as head waiter, served food to John Cheever, valet to an English baronet then staying in Boston.

“And it was great fun,” Dana said, in a lecture delivered at the University of Michigan forty years afterward. “There were seventy people or more, and at dinner they all came in and we served them. There was more entertainment in doing the duty than in getting away from it.”

It was at Brook Farm that Dana first made the acquaintance of Horace Greeley, who, himself a student of Fourier, was interested in the Roxbury experiment, so much more idealistic than Fourierism itself.

Dana took Brook Farm seriously, but he was not one of the poseurs of the colony. No smocks for him, no long hair! He wore a full, auburn beard, but he wore a beard all the rest of his life. He was a handsome, slender youth, and he got mental and physical health out of every minute at the farm. By day he was busy teaching, keeping the association’s books, milking, waiting on table, or caring for the fruit-trees. He was the most useful man on the farm. At night, when the others danced, he was at his books or his writings.

He wrote articles for the Harbinger, and for the Dial, which succeeded the Harbinger as the official organ of the Transcendentalists. Dr. Ripley was the editor of the Harbinger, and he had such brilliant contributors as James Russell Lowell and George William Curtis; but Dana was his mainstay. He wrote book-reviews, editorial articles and notes, and not a little verse. His “Via Sacra” is typical of the thoughtful youth:

Slowly along the crowded street I go,

Marking with reverent look each passer’s face,

Seeking, and not in vain, in each to trace

That primal soul whereof he is the show.

For here still move, by many eyes unseen,

The blessed gods that erst Olympus kept;

Through every guise these lofty forms serene

Declare the all-holding life hath never slept;

But known each thrill that in man’s heart hath been,

And every tear that his sad eyes have wept.

Alas for us! The heavenly visitants—

We greet them still as most unwelcome guests,

Answering their smile with hateful looks askance,

Their sacred speech with foolish, bitter jests;

But oh, what is it to imperial Jove

That this poor world refuses all his love?

A Mrs. Macdaniel, a widow, came to Brook Farm from Maryland with her son and two daughters. One of the daughters brought with her an ambition for the stage, but her destiny was to be Mrs. Dana. On March 2, 1846, in New York, Charles A. Dana and Eunice Macdaniel were married. That day, coincidentally, the fire insurance on the main building at Brook Farm lapsed, perhaps through the preoccupation of the recording secretary; and the next day this building, called the Phalanstery, was burned.

That was the beginning of the end of Brook Farm and of Dana’s secluded life. He went to work on the Boston Daily Chronotype for five dollars a week. It was a Congregational paper, owned and edited by Elizur Wright. When Wright was absent, Dana acted as editor, and on one of these occasions he caused the Chronotype to come out so “mighty strong against hell,” that Mr. Wright declared, years afterward, that he had to write a personal letter to every Congregational minister in Massachusetts, explaining that the apparent heresy was due to his having left the paper in the charge of “a young man without journalistic experience.”

In February, 1847, Dana went to New York, and Horace Greeley made him city editor of the Tribune at ten dollars a week. Later in that year Dana insisted on an increase of salary, and Greeley agreed to pay him fourteen dollars a week—a dollar less than his own stipend; but in consideration of this huge advance Dana was obliged to give all his talents to the Tribune.

Dana still nursed his desire to see Europe, but he had given up the idea of teaching in a German university. Newspaper work had captured him. Germany was still attractive, but now as a place of news, for the rumblings against the rule of Metternich were being heard in central Europe. And in France there was a sweep of socialism, a subject which still held the idealistic Dana, and the beginning of the revolution in Paris (February 24, 1848).

Dana told Greeley of his European ambition, but Greeley threw cold water on it, saying that Dana—not yet thirty—knew nothing about foreign politics. Dana asked how much the Tribune would pay for a letter a week if he went abroad “on his own,” and Greeley offered ten dollars, which Dana accepted. He made a similar agreement with the New York Commercial Advertiser and the Philadelphia North American, and contracted to send letters to the Harbinger and the Chronotype for five dollars a week.

“That gave me forty dollars a week for five letters,” said Dana afterward; “and when the Chronotype went up, I still had thirty-five dollars. On this I lived in Europe nearly eight months, saw plenty of revolutions, supported myself there and my family in New York, and came home only sixty-three dollars out for the whole trip.” Not a bad outcome for what was probably the first correspondence syndicate ever attempted.

The trip did wonders for Dana. He saw the foreign “improvers of mankind” in action, more violent than visionary; saw theory dashed against the rocks of reality. He came back a wiser and better newspaperman, with a knowledge of European conditions and men that served him well all his life. There is seen in some of his descriptions the fine simplicity of style that was later to make the Sun the most human newspaper.

Social experiments still interested Dana after his return to New York in the spring of 1849, but he was able to take a clearer view of their practicability than he had been in the Brook Farm days. He still favoured association and cooperation, and every sane effort toward the amelioration of human misery, but he now knew that there was no direct road to the millennium.

Once home, however, and settled, not only as managing editor, but as a holder of five shares of stock in the Tribune, Dana was kept busy with things other than socialistic theories. Slavery and the tariff were the overshadowing issues of the day.

Greeley was the great man of the Tribune office, but Dana, in the present-day language of Park Row, was the live wire almost from the day of his return from Europe. When Greeley went abroad, Dana took charge. Greeley now drew fifty dollars a week; Dana got twenty-five, Bayard Taylor twenty, George Ripley fifteen. Dana’s five shares of stock netted him about two thousand dollars a year in addition to his salary.

Here is a part of a letter which Dana wrote in 1852 to James S. Pike, the Washington correspondent of the Tribune:

KEENEST OF PIKES:

What a desert void of news you keep at Washington! For goodness’ sake, kick up a row of some sort. Fight a duel, defraud the Treasury, set fire to the fueling-mill, get Black Dan [Webster] drunk, or commit some other excess that will make a stir.

The solemn phrases of transcendentalism had vanished from the tip of Dana’s pen.

In the fight over slavery in the fifties, the effort of Greeley and Dana was against the further spread of the institution over new American territory, rather than for its complete overthrow. When Greeley was at the helm, the Tribune appeared to admit the possibility of secession, a forerunner of “Let the erring sisters depart in peace.” But when Dana was left in charge, the editorials pleaded for the integrity of the Union at any cost. Greeley was heart and soul for liberty, but his fist was not in the fight. Of the political situation in 1854, Henry Wilson wrote, in his “Rise and Fall of the Slave Power”:

At the outset Mr. Greeley was hopeless, and seemed disinclined to enter the contest. He told his associates that he would not restrain them; but, as for himself, he had no heart for the strife. They were more hopeful; and Richard Hildreth, the historian; Charles A. Dana, the veteran journalist; James S. Pike, and other able writers, opened and continued a powerful opposition in its columns, and did very much to rally and assure the friends of freedom and nerve them for the fight.

Dana went farther than Greeley cared to go, particularly in his attacks on the Democrats; so far, in fact, that Greeley often pleaded with him to stop. Greeley wrote to James S. Pike:

Charge Dana not to slaughter anybody, but be mild and meek-souled like me.

Greeley wrote to Dana from Washington, where Dana’s radicalism was making his colleague uncomfortable:

Now I write once more to entreat that I may be allowed to conduct the Tribune with reference to the mile wide that stretches either way from Pennsylvania Avenue. It is but a small space, and you have all the world besides. I cannot stay here unless this request is complied with. I would rather cease to live at all.

If you are not willing to leave me entire control with reference to this city, I ask you to call the proprietors together and have me discharged. I have to go to this and that false creature—Lew Campbell, for instance—yet in constant terror of seeing him guillotined in the next Tribune that arrives, and I can’t make him believe that I didn’t instigate it. So with everything here. If you want to throw stones at anybody’s crockery, aim at my head first, and in mercy be sure to aim well.

Again Greeley wrote to Dana:

You are getting everybody to curse me. I am too sick to be out of bed, too crazy to sleep, and am surrounded by horrors.... I can bear the responsibilities that belong to me, but you heap a load on me that will kill me.

With all Dana’s editorial work—and he and Greeley made the Tribune the most powerful paper of the fifties, with a million readers—he found time for the purely literary. He translated and published a volume of German stories and legends under the title “The Black Ant.” He edited a book of views of remarkable places and objects in all countries. In 1857 was published his “Household Book of Poetry,” still a standard work of reference. He was criticised for omitting Poe from the first edition, and at the next printing he added “The Raven,” “The Bells,” and “Annabel Lee.” Poe and Cooper were among the literary gods whom Dana refused to worship in his youth, but in later life he changed his opinion of the poet.

With George Ripley, his friend in Harvard, at Brook Farm, and in the Tribune office, Dana prepared the “New American Encyclopedia,” which was published between 1858 and 1863. It was a huge undertaking and a success. Dana and Ripley carefully revised it ten years afterward. In 1882, with Rossiter Johnson, Dana edited and published a collection of verse under the title “Fifty Perfect Poems.”

Although Dana persisted that the Union must not fall, Greeley still believed, as late as December, 1860, that it would “not be found practical to coerce” the threatening States into subjection. When war actually came, however, Greeley at last adopted the policy of “No compromise, no concessions to traitors.”

The Tribune’s cry, “Forward to Richmond!” sounded from May, 1861, until Bull Run, was generally attributed to Dana. Greeley himself made it plain that it was not his:

I wish to be distinctly understood as not seeking to be relieved from any responsibility for urging the advance of the Union army in Virginia, though the precise phrase, “Forward to Richmond!” was not mine, and I would have preferred not to reiterate it. Henceforth I bar all criticism in these columns on army movements. Now let the wolves howl on! I do not believe they can goad me into another personal letter.

As a matter of fact, “Forward to Richmond!” was phrased by Fitz-Henry Warren, then head of the Tribune’s correspondence staff in Washington. He came from Iowa, where in his youth he was editor of the Burlington Hawkeye. He resigned from the Tribune late in 1861 to take command of the First Iowa Cavalry, which he organized. In 1862 he became a brigadier-general, and he was later brevetted a major-general. In 1869 he was the American minister to Guatemala. From being one of the men around Greeley he became one of the men with Dana, and in 1875–1876 he did Washington correspondence for the Sun, and wrote many editorial articles for it.

In 1861 Dana was an active advocate of Greeley’s candidacy for the United States Senate, and almost got him nominated. If Greeley had gone to the Senate, Dana might have continued on the Tribune; but it became evident, before the war was a year old, that one newspaper was no longer large enough for both men. The sprightly, aggressive, unhesitating, and practical Dana, and the ambitious, but eccentric and somewhat visionary Greeley found their paths diverging. The circumstances under which they parted were thus described by Dana in a letter to a friend:

On Thursday, March 27, I was notified that Mr. Greeley had given the stockholders notice that I must leave, or he would, and that they wanted me to leave accordingly. No cause of dissatisfaction being alleged, and H. G. having been of late more confidential and friendly than ever, not once having said anything betokening disaffection to me, I sent a friend to him to ascertain if it was true, or if some misunderstanding was at the bottom of it. My friend came and reported that it was true, and that H. G. was immovable.

On Friday, March 28, I resigned, and the trustees at once accepted it, passing highly complimentary resolutions and voting me six months’ salary after the date of my resignation. Mr. Ripley opposed the proceedings in the trustees, and, above all, insisted on delay in order that the facts might be ascertained; but all in vain.

On Saturday, March 29, Mr. Greeley came down, called another meeting of the trustees, said he had never desired me to leave, that it was a damned lie that he had presented such an alternative as that he or I must go, and finally sent me a verbal message desiring me to remain as a writer of editorials; but has never been near me since to meet the “damned lie” in person, nor written one word on the subject. I conclude, accordingly, that he is glad to have me out, and that he really set on foot the secret cabal by which it was accomplished. As soon as I get my pay for my shares—ten thousand dollars less than I could have got for them a year ago—I shall be content.

That was the undramatic and somewhat disappointing end of Dana’s fourteen years on the Tribune. He was forty-three years old and not rich. All he had was what he got from the sale of his Tribune stock and what he had saved from the royalties on his books.

From the literary view-point he was doubtless the best-equipped newspaperman in America, but there was no great place open for him then.

Dana’s work on the Tribune had attracted the attention of most of the big men of the North, including Edwin M. Stanton, who in January, 1862, was appointed Secretary of War in place of Simon Cameron. Stanton asked Dana to come into the War Department, and assigned him to service upon a commission to audit unsettled claims against the quartermaster’s department. While in Memphis on this work he first met General Grant, then prosecuting the war in the West.

In the autumn of 1862, Stanton offered to Dana a post as second Assistant Secretary of War, and Dana, having accepted, told a newspaperman of his appointment. When the news was printed, the irascible Stanton was so much annoyed—although without any apparent reason—that he withdrew the appointment. Dana then became a partner with George W. Chadwick, of New York, and Roscoe Conkling, of Utica, in an enterprise for buying cotton in that part of the Mississippi Valley which the Union army occupied.

Dana and Chadwick went to Memphis in January, 1863, armed with letters from Secretary Stanton to General Grant and other field commanders. But no sooner had their cotton operations begun than Dana saw the evil effect that this traffic was having. It had aroused a fever of speculation. Army officers were forming partnerships with cotton operators, and even privates wanted to buy cotton with their pay. The Confederacy was being helped rather than hindered.

Disregarding his own fortunes, Dana called upon General Grant and advised him to “put an end to an evil so enormous, so insidious and so full of peril to the country.” Grant at once issued an order designed to end the traffic, but the cotton-traders succeeded in having it nullified by the government.

Then Dana went to Washington, saw President Lincoln and Secretary Stanton, and convinced them that the cotton trade should be handled by the Treasury Department. As a result of Dana’s visit, Lincoln issued his proclamation declaring all commercial intercourse with seceded States to be unlawful. Thus Dana patriotically worked himself out of a paying business.

Yet his unselfishness was not without a reward. It reestablished his friendly relations with Stanton, and won for him the President’s confidence.

Just then there was an important errand to be done. Many complaints had been made against General Grant. Certain temperance people had told Lincoln that Grant was drinking heavily, and although Lincoln jested—“Can you tell me where Grant buys his liquor? I would like to distribute a few barrels of the same brand among my other major-generals”—he really wished to have all doubts settled.

The President and Mr. Stanton chose Dana for the mission. It was an open secret. If Grant did not know that Dana was coming to make a report on his conduct, all the general’s staff knew it. General James Harrison Wilson, biographer of Dana—and, with Dana, biographer of Grant—wrote of this situation:

It was believed by many that if he [Dana] did not bring plenary authority to actually displace Grant, the fate of that general would certainly depend upon the character of the reports which the special commissioner might send to Washington in regard to him.

Wilson was at this time the inspector-general of Grant’s army. He consulted with John A. Rawlins, Grant’s austere young adjutant-general and actual chief of staff, and the two officers agreed that Dana must be taken into complete confidence. Wilson wrote:

We sincerely believed that Grant, whatever might be his faults and weaknesses, was a far safer man to command the army than any other general in it, or than any that might be sent to it from another field.

Dana and Wilson and Rawlins made the best of a delicate, difficult situation. Dana was taken into headquarters “on the footing of an officer of the highest rank.” His commission was that of a major of volunteers, but his functions were so important that he was called “Mr. Dana” rather than “Major Dana.” Dana himself never used the military title.

Dana sent his first official despatches to Stanton in March, 1863, from before Vicksburg. Grant’s staff made clear to him the plan of the turning movement by which the gunboats and transports were to be run past the Vicksburg batteries while the army marched across the country, and Dana made most favourable reports to Washington on the general’s strategy.

Dana saw not only real warfare, but a country that was new to him. After a trip into Louisiana he wrote to his friend, William Henry Huntington:

During the eight days that I have been here, I have got new insight into slavery, which has made me no more a friend of that institution than I was before.... It was not till I saw these plantations, with their apparatus for living and working, that I really felt the aristocratic nature of it.

Under a flag of truce Dana went close to Vicksburg, where he was met by a Confederate major of artillery:

Our people entertained him with a cigar and a drink of whisky, of course, or, rather, with two drinks. This is an awful country for drinking whisky. I calculate that on an average a friendly man will drink a gallon in twenty-four hours. I wish you were here to do my drinking for me, for I suffer in public estimation for not doing as the Romans do.

Dana was with Grant on the memorable night of April 16, 1863, when the squadron of gunboats, barges, and transports ran the Vicksburg forts. From that time on until July he accompanied the great soldier. It was Dana who received and communicated Stanton’s despatch giving to Grant “full and absolute authority to enforce his own commands, and to remove any person who, by ignorance, inaction, or any cause, interferes with or delays his operations.”

Dana was in many marches and battles. Like the officers of Grant’s staff, he slept in farmhouses, and ate pork and hardtack or what the land provided. The move on Vicksburg was a brilliant campaign, and in ten days Dana saw as much of war as most men of the Civil War saw in three years. Dana sent despatches to Washingt