CHAPTER X

DANA: HIS “SUN” AND ITS CITY

The Period of the Great Personal Journalists.—Dana’s Avoidance of Rules and Musty Newspaper Conventions.—His Choice of Men and His Broad Definition of News.

WHEN Dana came into control of the Sun, the city of New York, which then included only Manhattan and the Bronx, had less than a million population, yet it supported, or was asked to support, almost as many newspapers as it has to-day. That was the day of the great personal editor. Bennett had his Herald, with James Gordon Bennett, Jr., as his chief helper. Horace Greeley was known throughout America as the editor of the Tribune. Henry J. Raymond was at the head of the Times. Manton Marble—who died in England in 1917—was the intellectual chief of the highly intellectual World.

The greatest Republican politician of that day, Thurlow Weed, was the editor of the Commercial Advertiser. He had just changed his political throne from the Astor House to the comparatively new Fifth Avenue Hotel. Weed was seventy-one years old, but not the Nestor of New York editors, for William Cullen Bryant was three years his senior and still the active editor of the Evening Post. The Evening Express, later to be incorporated with the Mail, was ruled by the brothers Brooks, James as editor-in-chief and Erastus as manager. David M. Stone ran the Journal of Commerce. Ben Wood owned the only penny paper in town—the Evening News. Marcus M. Pomeroy, better known as Brick Pomeroy, had just started his sensational sheet, the Democrat, on the strength of the reputation he had won in the West as editor of the La Crosse Democrat. Later he changed the title of the Democrat to Pomeroy’s Advance Thought.

These were the men who assailed or defended the methods of the reconstruction of the South; who stood up for President Johnson, or cried for his impeachment; who supported the Presidential ambitions of Grant, then the looming figure in national politics, or decried the elevation of one whose fame had been exclusively military; who hammered at the wicked gates of Tammany Hall, or tried to excuse its methods.

Tweed had not yet committed his magnificent atrocities of loot, but he was practically the boss of the city, at the same time a State Senator and the street commissioner. John Kelly, then forty-six—two years the senior of the boss—was sheriff of New York. Richard Croker, who was to succeed Kelly as Kelly succeeded Tweed at the head of the wigwam, was then a stocky youth of twenty-five, engineer of a fire-department steamer and the leader of the militant youth of Fourth Avenue. He was already actively concerned in politics, allied with the Young Democracy that was rising against Tweed. In the year when Dana took the Sun, Croker was elected an alderman.

A slender boy of ten played in those days in Madison Square Park, hard by his home in East Twentieth Street, just east of Broadway. His name was Theodore Roosevelt.

New York’s richest man was William B. Astor, with a fortune of perhaps fifty million dollars. He was then seventy-six years old, but he walked every day from his home in Lafayette Place—from its windows he could see the Bowery, which had been a real bouwerie in his boyhood—to the little office in Prince Street where he worked all day at the tasks that fell upon the shoulders of the Landlord of New York. He probably never had heard of John D. Rockefeller, a prosperous young oil man in the Middle West.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, only two years younger than Astor, was president of the New York Central Railroad, and was linking together the great railway system that is now known by his name, battling the while against the strategy of Jay Gould and his sinister associates. By far the most imposing figure in financial America, Vanderbilt had everything in the world that he wanted—except Dexter, and that great trotter was in the stable of Robert Bonner, who was not only rich enough to keep Dexter, but could afford to pay Henry Ward Beecher thirty thousand dollars for a novel, “Norwood,” to be printed serially in the Ledger.

Only one other New Yorker of 1868 ranked in wealth with Astor and Vanderbilt—Alexander T. Stewart, whose yearly income was perhaps greater than either’s. He was then worth about thirty million dollars, and he had astonished the business world by building a retail shop on Broadway, between Ninth and Tenth Streets—now half of Wanamaker’s—at a cost of two millions and three-quarters.

In Wall Street the big names were August Belmont, Larry Jerome, Jay Gould, Daniel Drew, and Jim Fisk. Gould and Fisk were doing what they pleased with Erie stock. They and the leaders of Tammany Hall, like Tweed and Peter B. Sweeny and Slippery Dick Connelly, hatched schemes for fortunes as they sat either in the Hoffman House, where Fisk sometimes lived, or at dinner in the house in West Twenty-Third Street, where the only woman at table was Josie Mansfield.

Of the great hotels of that day not more than one or two are left. The Fifth Avenue then took rank not only as the finest hostelry in New York, but perhaps in the world. The Hoffman House was running as a European-plan hotel. It had not yet become a Democratic headquarters, for the Democrats still preferred the New York, on the American plan. The other big “everything included” hotels were the St. Nicholas, where Middle West folk stayed, and the Metropolitan, where the exploiter of mining-stock held forth. Among the smaller and European-plan hotels were the St. James, the St. Denis, the Everett, and the Clarendon, all more or less fashionable, and the Brevoort and the Barcelona, patronized largely by foreigners.

The restaurants were limited in number, for New York had not acquired the restaurant habit as strongly as it has it now. When you have mentioned Delmonico’s, Taylor’s, Curet’s, and the Café de l’Université, you have almost a complete list of the places to which fashion drove in its brougham after the theatre.

The playhouses were plentiful enough, considering the size of the city. None was north of Twenty-Fourth Street. Wallack’s, at Broadway and Thirteenth Street, was considered the best theatre in America. The Grand Opera House, at Eighth Avenue and Twenty-Third Street, was called the handsomest. Surely it was costly enough, for Jim Fisk, who had his own way with Erie finances, paid eight hundred thousand dollars of the railroad stockholders’ gold for it, to buy it from the railroad later with some of its own stock, of problematical value.

THE FIRST NUMBER OF “THE SUN” UNDER DANA

The Title Heading Has Remained Unchanged for Fifty Years.

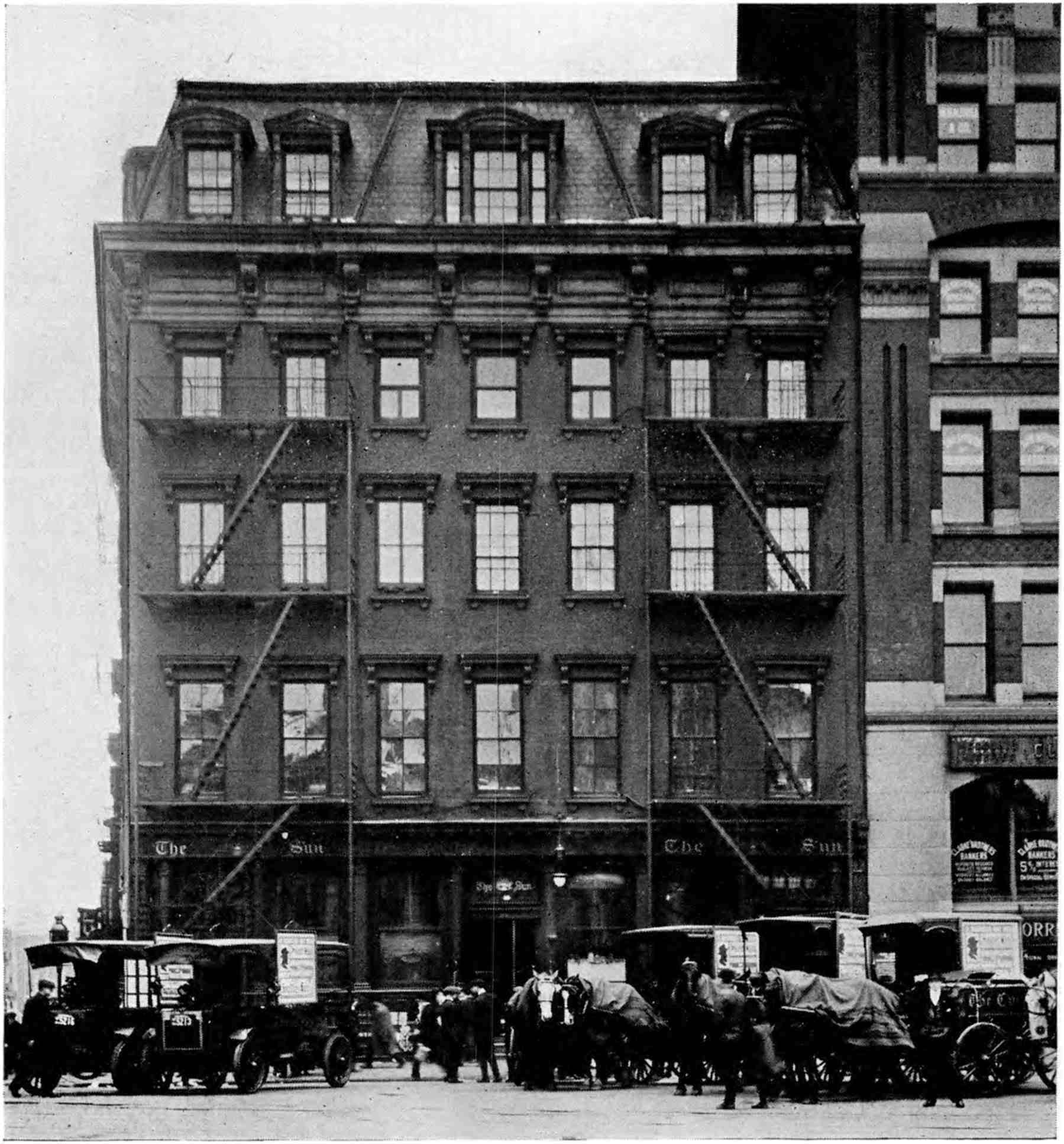

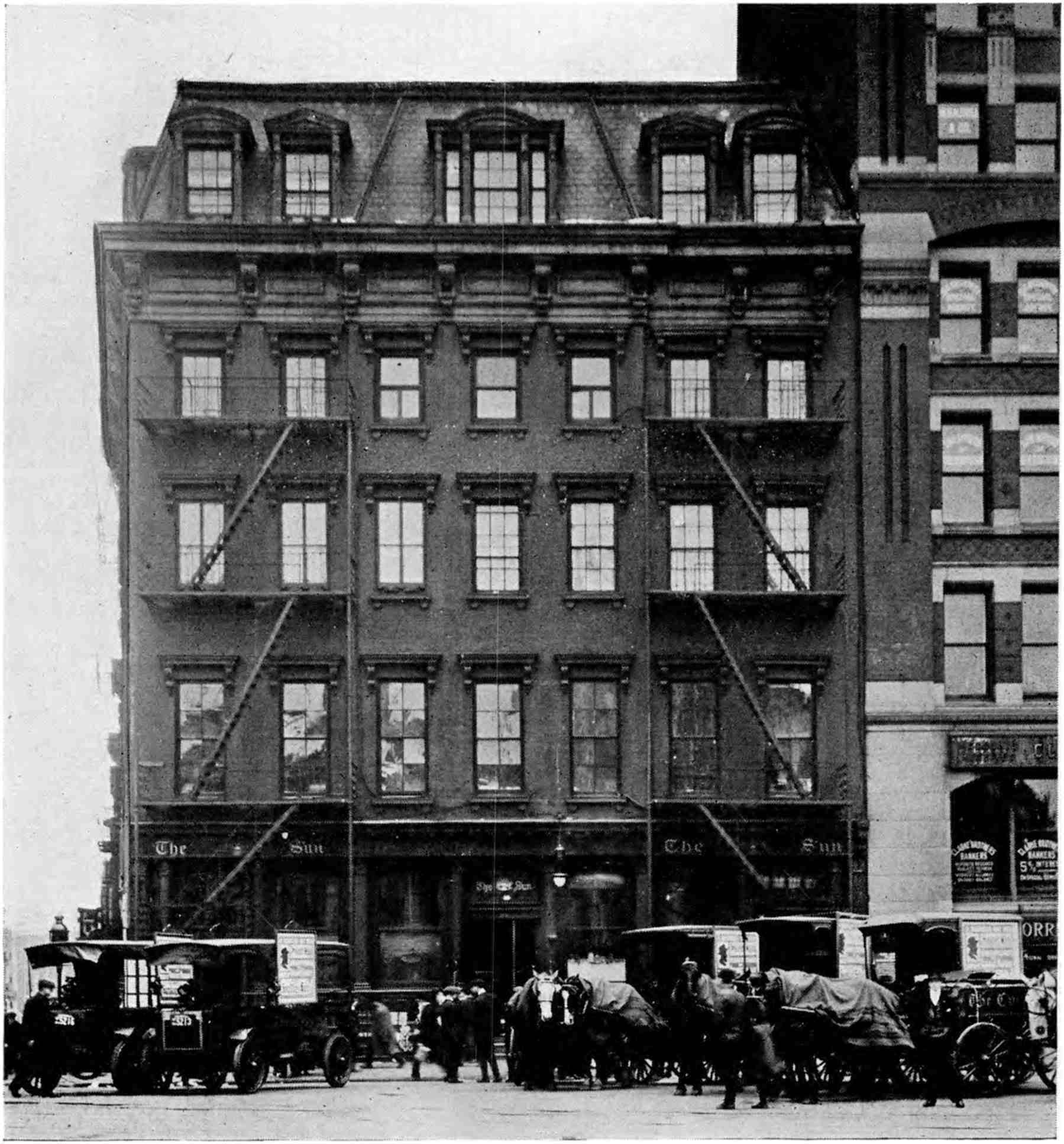

THE HOME OF “THE SUN” FROM 1868 TO 1915

The Famous Old Building at Nassau and Spruce Streets.

The Academy of Music, at Fourteenth Street and Irving Place, housed Italian opera. The Théâtre Français, also on Fourteenth Street, but near Sixth Avenue, was the original home in this country of opera bouffe. Opera burlesque prevailed at the Fifth Avenue Opera House, on West Twenty-Fourth Street. The Olympic, on Broadway near Houston, had been built for Laura Keene; it was there that Edward A. Sothern first appeared under his own name. Barney Williams, the Sun’s first newsboy, was managing the Broadway Theatre, in Broadway near Broome Street. Edwin Booth was building a fine theatre of his own at Sixth Avenue and Twenty-Third Street—destined to score an artistic but not a financial success.

Club life was well advanced. In the house of the Century Club, then in East Fifteenth Street, the member would come upon Bayard Taylor, George William Curtis, Parke Godwin, William Allen Butler, Edwin Booth, Lester Wallack, John Jacob Astor, August Belmont. The Union League was young, and was just about to move from a rented home at Broadway and Seventeenth Street to the Jerome house, at Madison Avenue and Twenty-Sixth Street, where it remained until 1881, then to go to its present home in Fifth Avenue at Thirty-Ninth Street. In the Union League could be seen John Jay, Horace Greeley, William E. Dodge, and other enthusiastic Republicans. Upon occasion Mr. Dana went there, but he was not an ardent clubman.

All in all, the New York of Dana’s first year as an absolute editor was an interesting island, with just about as much of virtue and vice, wisdom and folly, sunlight and drabness, as may be found on any island of nine hundred thousand people. He did not set out to reform it. He did not try to turn the general journalism of that day out of certain deep grooves into which it had sunk. He had his own ideas of what news was, how it should be written, how displayed; but they were ideas, not theories. He was not perturbed because the Sun had not handled a big story just the way the Herald or the Tribune dished it up; nor was it of the slightest consequence to him what Mr. Bennett or Mr. Greeley thought of the way the Sun used the story.

Dana made no rules. Other newspapers have printed commandments for their writers, but the Sun has never wasted a penny’s worth of paper on rules. If there ever was a rule in the office, it was “Be interesting,” and it was not only an unwritten rule, but generally an unspoken one.

Dana’s realization that journalism was a profession which could be neither guided nor governed by set rules was expressed in a speech made by him before the Wisconsin Editorial Association at Milwaukee, in 1888:

There is no system of maxims or professional rules that I know of that is laid down for the guidance of the journalist. The physician has his system of ethics and that sublime oath of Hippocrates which human wisdom has never transcended. The lawyer also has his code of ethics and the rules of the courts and the rules of practice which he is instructed in; but I have never met with a system of maxims that seemed to me to be perfectly adapted to the general direction of a newspaperman. I have written down a few principles which occurred to me, which, with your permission, gentlemen, I will read for the benefit of the young newspapermen here to-night:

Get the news, get all the news, get nothing but the news.

Copy nothing from another publication without perfect credit.

Never print an interview without the knowledge and consent of the party interviewed.

Never print a paid advertisement as news-matter. Let every advertisement appear as an advertisement; no sailing under false colors.

Never attack the weak or the defenseless, either by argument, by invective, or by ridicule, unless there is some absolute public necessity for so doing.

Fight for your opinions, but do not believe that they contain the whole truth or the only truth.

Support your party, if you have one; but do not think all the good men are in it and all the bad ones outside of it.

Above all, know and believe that humanity is advancing; that there is progress in human life and human affairs; and that, as sure as God lives, the future will be greater and better than the present or the past.

In other words, don’t loaf, don’t cheat, don’t dissemble, don’t bully, don’t be narrow, don’t grouch. Mr. Dana’s maxims were as applicable to any other business as to his own. In a lecture delivered at Cornell University in 1894—three years before his death—Mr. Dana uttered more maxims “of value to a newspaper-maker”:

Never be in a hurry.

Hold fast to the Constitution.

Stand by the Stars and Stripes. Above all, stand for liberty, whatever happens.

A word that is not spoken never does any mischief.

All the goodness of a good egg cannot make up for the badness of a bad one.

If you find you have been wrong, don’t fear to say so.

All these maxims were quite as useful to the merchant as to the newspaperman. They related to the broad conduct of life. They counselled against folly, so far as the making of newspapers was concerned, but they did not convey the mysterious prescription with which Dana revived American journalism from that trance in which it had forgotten that everybody is human and that the English language is alive and fluid.

If there had been rules by which a living newspaper could be made from men and ink and wood-pulp, Dana would have known them; but there were none, nor are there now. The present editor of the Sun, E. P. Mitchell, who knew Dana better than any other man knew him, said in an address at the Pulitzer School of Journalism a few years ago:

Mr. Dana used to lecture on journalism sometimes, when he was invited, but in the bottom of my heart I don’t believe he had any theories of journalism other than common sense and free play for individual talent when discovered and available. And I do remember distinctly that when he sent Mr. Joseph Pulitzer, then fresh from St. Louis, on to Washington to report in semieditorial correspondence the critical stage of the electoral controversy of 1876, Mr. Dana did not think it necessary to instruct that correspondent to assimilate his style to the Sun’s methods and traditions. Never was a job of momentous journalistic importance better done in the absence of plain sailing directions; but that, perhaps, was due partly to the fact that Mr. Pulitzer was somewhat of an individualist himself.

For the ancient common law of journalism, as derived from England, and perhaps before that from away back in Bœotia, Mr. Dana didn’t care one comic supplement. If anybody had asked Mr. Dana to compile a set of specific directions for running a newspaper, his reply, I am sure, would have been something like this:

“Heaven bless you, young man, there aren’t any rules! Go ahead and write when you have something to say, not when you think you ought to say something. I’ll edit out the nonsense. And, by the way, unless there happens to have been born into your noddle a little bit of the native aptitude, you ought to go and be a lawyer or a farmer or a banker or a great statesman.”

Mr. Dana had no regard for typographical gymnastics. To him a head-line was something to fill the mind rather than the eye. He knew the utter impossibility of trying to startle the reader eight times in as many adjacent columns—a feat which Mr. Bennett and some of his imitators seemed to consider feasible. Surprise is not the only emotion upon which a newspaper can play. The Sun stretched all the human octaves from horror to amusement, but the keys of horror were only touched when it was necessary.

Make rules for news? How is it possible to make a rule for something the value of which lies in the fact that it is the narrative of what never had happened, in exactly the same way, before? John Bogart, a city editor of the Sun who absorbed the Dana idea of news and the handling thereof, once said to a young reporter:

“When a dog bites a man, that is not news, because it happens so often. But if a man bites a dog, that is news.”

The Sun always waited for the man to bite the dog.

Here is Mr. Dana’s own definition of news:

The first thing which an editor must look for is news. If the newspaper has not the news it may have everything else, yet it will be comparatively unsuccessful; and by news I mean everything that occurs, everything which is of human interest, and which is of sufficient interest to arrest and absorb the attention of the public or of any considerable part of it.

There is a great disposition in some quarters to say that the newspapers ought to limit the amount of news that they print; that certain kinds of news ought not to be published. I do not know how that is. I am not prepared to maintain any abstract proposition in that line; but I have always felt that whatever the divine Providence permitted to occur I was not too proud to report.

A belief has been accepted in some quarters that the Sun of Dana’s time preferred college men for its staff. This was in a way false, but it is true that a great many of the Sun’s young men came from the colleges. Mr. Dana’s views on the matter of educational equipment were quite plainly expressed by himself:

If I could have my way, every young man who is going to be a newspaperman, and who is not absolutely rebellious against it, should learn Greek and Latin after the good old fashion. I had rather take a young fellow who knows the “Ajax” of Sophocles, and has read Tacitus, and can scan every ode of Horace—I would rather take him to report a prize-fight or a spelling-match, for instance, than to take one who has never had those advantages.

At the same time, the cultivated man is not in every case the best reporter. One of the best I ever knew was a man who could not spell four words correctly to save his life, and his verb did not always agree with the subject in person and number; but he always got the fact so exactly, and he saw the picturesque, the interesting, the important aspect of it so vividly, that it was worth another man’s while, who possessed the knowledge of grammar and spelling, to go over the report and write it out.

Now, that was a man who had genius; he had a talent the most indubitable, and he got handsomely paid in spite of his lack of grammar, because after his work had been done over by a scholar it was really beautiful. But any man who is sincere and earnest and not always thinking about himself can be a good reporter. He can learn to ascertain the truth; he can acquire the habit of seeing.

When he looks at a fire, what is the most important thing about that fire? Here, let us say, are five houses burning; which is the greatest? Whose store is that which is burning? And who has met with the greatest loss? Has any individual perished in the conflagration? Are there any very interesting circumstances about the fire? How did it occur? Was it like Chicago, where a cow kicked over a spirit-lamp and burned up the city?

All these things the reporter has to judge about. He is the eye of the paper, and he is there to see which is the vital fact in the story, and to produce it, tell it, write it out.

Dana saw the usefulness to a reporter of certain qualities which are acquired neither at school nor in the office:

In the first place, he must know the truth when he hears it and sees it. There are a great many men who are born without that faculty, unfortunately. But there are some men that a lie cannot deceive; and that is a very precious gift for a reporter, as well as for anybody else. The man who has it is sure to live long and prosper; especially if he is able to tell the truth which he sees, to state the fact or the discovery that he has been sent out after, in a clear and vivid and interesting manner.

The invariable law of the newspaper is to be interesting. Suppose you tell all the truths of science in a way that bores the reader; what is the good? The truths don’t stay in the mind, and nobody thinks any the better of you because you have told the truth tediously. The reporter must give his story in such a way that you know he feels its qualities and events and is interested in them.

Dana was catholic not only in his taste for news, but in his idea of the manner of writing it. Nothing gave him more uneasiness than to find that a Sun man was drifting into a stereotyped way of handling a news story or writing an editorial article. Even as he advised young men to read everything from Shakespeare and Milton down, he repeatedly warned them against the imitation, unconscious or otherwise, of another’s style:

Do not take any model. Every man has his own natural style, and the thing to do is to develop it into simplicity and clearness. Do not, for instance, labor after such a style as Matthew Arnold’s—one of the most beautiful styles that has ever been seen in any literature. It is no use to try to get another man’s style or to imitate the wit or the mannerisms of another writer. The late Mr. Carlyle, for example, did, in my judgment, a considerable mischief in his day, because he led everybody to write after the style of his “French Revolution,” and it became pretty tedious.

If a writer could not keep on without aping the literary fashion of another, then he was not for the Sun. Dana wanted good English always, but a constant spice of variety in the treatment of a subject, and in the style itself; therefore he chose a variety of men.

If he believed that the best report of a ship-launching could be written by a longshoreman, he would have hired the hard-handed toiler and assigned him to the job. He wanted men who would look at the world with open eyes and find the new things that were going on. Dana knew that they were going on. His vision had not been narrowed by too close application to newspaper offices where editors and managing editors had handled the stock stories year in and year out in the same wearisome way.

To Dana life was not a mere procession of elections, legislatures, theatrical performances, murders, and lectures. Life was everything—a new kind of apple, a crying child on the curb, a policeman’s epigram, the exact weight of a candidate for President, the latest style in whiskers, the origin of a new slang expression, the idiosyncrasies of the City Hall clock, a strange four-master in the harbour, the head-dresses of Syrian girls, a new president or a new football coach at Yale, a vendetta in Mulberry Bend—everything was fish to the great net of Dana’s mind.

Human interest! It is an old phrase now, and one likely to cause lips to curl along Park Row. But the art of picking out the happenings of every-day life that would appeal to every reader, if so depicted that the events lived before the reader’s eye, was an art that did not exist until Dana came along. Ben Day knew the importance of the trifles of life and the hold they took on the people who read his little Sun, but it remained for Dana to bring out in journalism the literary quality that made the trifle live. Whether it was an item of three lines or an article of three columns, it must have life, or it had no place in the Sun.

Dana did not teach his men how to do it. If he taught them anything, it was what not to do. His men did the work he wanted them to do, not by following instructions, but by being unhampered by instructions. He set the writer free and let him go his own way to glory or failure. There were no conventions except those of decency, of respect for the English language. Because newspapermen had been doing a certain thing in a certain way for a century, Dana could not see why he and his men should go in the same wagon-track. With a word or an epigram he destroyed traditions that had fettered the profession since the days of the Franklin press.

One day he held up a string of proofs—a long obituary of Bismarck, or Blaine, or some celebrity who had just passed away.

“Mr. Lord,” he said to his managing editor, “isn’t that a lot of space to give to a dead man?”

Yet the next day the same Dana came from his office to the city editor’s desk to inquire who had written a certain story two inches long, and, upon learning, went over to the reporter who was the author.

“Very good, young man, very good,” he said, pointing to the item. “I wish I could write like that!”

Names of writers meant nothing to Dana. He judged everything that was printed in the Sun, or offered to it for publication, on its own merits. He went through manuscript with uncanny speed, the gaze that seemed to travel only down the centre of the page really taking in the whole substance. A dull article from a celebrity he returned to its envelope with the note “Respectfully declined,” and without a thought of the author’s surprise, or possibly rage. But over a poem from an up-State unknown he might spend half an hour if the verses contained the germ of an idea new to him.

One clergyman who had come into literary prominence offered to write some articles for the Sun. Dana told him he might try. The clergyman evidently had a notion that the Sun’s cleverness was a worldly, reckless devilishness, and he adapted the style of his first article to what he supposed was the tone of the paper. Dana read it, smiled, wrote across the first page “This is too damned wicked,” and mailed it back to the misguided author.

He was a patient man. A clerk in the New York post-office copied by hand Edward Everett Hale’s story, “The Man Without a Country,” and offered it to the Sun—as original matter—for a hundred dollars. It was suggested to Mr. Dana that the poor fool should be exposed.

“No,” said Dana, “mark it ‘Respectfully declined,’ and send it back to him. He has been honest enough to enclose postage-stamps.”