CHAPTER XIII

DANA’S FAMOUS RIVALS PASS

The Deaths of Raymond, Bennett, and Greeley Leave Him the Dominant Figure of the American Newspaper Field.—Dana’s Dream of a Paper Without Advertisements.

FOUR years after he became the master of the Sun, and a quarter of a century before death took him from it, Dana found himself the Nestor of metropolitan journalism. Of the three other great New York editors of Dana’s time—three who had founded their own papers and lived with those papers until the wing of Azrael shut out the roar of the presses—Raymond had been the first, and the youngest, to go; for his end came when he was only forty-nine, eighteen years after the establishment of his Times.

Bennett, the inscrutable monarch of the Herald, died in 1872, three years after Raymond, but Bennett, who did not establish the Herald until he was forty, had owned it, and had given every waking hour to its welfare, for thirty-seven years. The year of Bennett’s death saw the passing of the unfortunate Greeley, broken in body and mind from his fatuous chase of public office, within three weeks of his defeat for the presidency. As the sprightly young editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, Colonel Henry Watterson, wrote in his paper in January, 1873:

Mr. Bryant being no longer actively engaged in newspaper work, Mr. Dana is left alone to tell the tale of old-time journalism in New York. He, of all his fellow editors of the great metropolis, has passed the period of middle age; though—years apart—he is as blithe and nimble as the youngest of them, and has performed, with the Sun, a feat in modern newspaper practice that entitles him to the stag-horns laid down at his death by James Gordon Bennett. Mr. Dana is no less a writer and scholar than an editor; as witness his sketch of Mr. Greeley, which for thorough character-drawing is unsurpassed. In a word, Mr. Dana at fifty-three is as vigorous, sinewy, and live as a young buck of thirty-five or forty.

His professional associates were boys when he was managing editor of the Tribune. Manton Marble was at college at Rochester, and Whitelaw Reid was going to school in Ohio. Young Bennett and Bundy were wearing short jackets.

They were rough-and-tumble days, sure enough, even for New York. There was no Central Park. Madison Square was “out of town.” Franconi’s Circus, surnamed a “hippodrome,” sprawled its ugly wooden towers, minarets, and sideshows over the ground now occupied by the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Miss Flora McFlimsy of the opposite square had not come into being; nay, Madison Square itself existed in a city ordinance merely, and, like the original of Mr. Praed’s Darnell Park, was a wretched waste of common, where the boys skated and played shinny.

The elder Harpers stood in the shoes now worn by their sons, who were off at boarding-school. George Ripley was as larky as John Hay is. Delmonico’s, down-town, was the only Delmonico’s. The warfare between the newspapers constituted the most exciting topic of the time. Bennett was “Jack Ketch,” Raymond was the “little villain,” and Greeley was by turns an “incendiary,” a “white-livered poltroon,” and a “free-lover.” Parke Godwin and Charles A. Dana were managing editors respectively; both scholars and both, as writers, superior to all the rest, except Greeley, who, as a newspaper writer, never had a superior.

The situation is changed completely. Bennett, Greeley, and Raymond are dead. Dana and Godwin, both about of an age, stand at the head of New York journalism; while Reid, Marble, and Jennings, all young men, wear the purple of a new era.

Will it be an era of reforms? There are signs that it will be. Marble is a recruit. Reid is essentially a man of the world. Jennings is an Englishman. One would think that these three, led by two ripe scholars and gentlemen like Godwin and Dana, would alter the character of the old partisan warfare in one respect at least, and that if they have need to be personal, they will be wittily so, and not brutally and dirtily personal; the which will be an advance.

There will never be an end to the personality of journalism. But there is already an end of the efficacy of filth. In this, as in other things, there are fashions. What ill thing, for example, can be said personally injurious of Reid, Marble, Jennings, Bundy, and the rest, all hard-working, painstaking men, without vices or peculiarities, who do not invite attack?

On the whole, the newspaper prospect in New York is very good. There will be, perhaps, less of what we call “character” in New York journalism, but more usefulness, honesty, and culture and as the New York dailies, like the New York milliners, set the fashion, these excellent qualities will diffuse themselves over the country. They may even reach Nashville and Memphis. It is an age of miracles. Who can tell?

“There will never be an end to the personality of journalism.” It is curious to note in passing that Henry Watterson, who retired from the active editorship of the Courier-Journal on August 7, 1918, after fifty years’ service, was the last of the men who, according to the measure of forty years ago, were “personal journalists.” “Dana says,” “Greeley says,” “Raymond says”—such oral credits are no longer given by the readers of the really big and reputable newspapers of New York to the men who write opinions. “Henry Watterson says” was the last of the phrases of that style.

Dana believed in personal journalism and thought it would not pass away. A few days after the death of Horace Greeley, the editor of the Sun printed his views on the subject:

A great deal of twaddle is uttered by some country newspapers just now over what they call personal journalism. They say that now that Mr. Bennett, Mr. Raymond, and Mr. Greeley are dead, the day for personal journalism is gone by, and that impersonal journalism will take its place. That appears to be a sort of journalism in which nobody will ask who is the editor of a paper or the writer of any class of article, and nobody will care.

Whenever in the newspaper profession a man rises up who is original, strong, and bold enough to make his opinions a matter of consequence to the public, there will be personal journalism; and whenever newspapers are conducted only by commonplace individuals whose views are of no interest to the world and of no consequence to anybody, there will be nothing but impersonal journalism.

And this is the essence of the whole question.

For all that, Dana must have felt lonely, for at that moment, at any rate, the new chiefs of the Sun’s rivals did not measure up to the heights of their predecessors. To Dana, the trio that had passed were men worthy of his steel, and worthy, each in his own way, of admiration. Toward Greeley, in spite of the circumstances under which Dana left the Tribune, the editor of the Sun showed a kindly spirit; not only in his support of Greeley for the presidency, which may have sprung from Dana’s aversion to Grantism, but in his general attitude toward the brilliant if erratic old man. As for Bennett, Dana frankly believed him to be a great newspaperman, and never hesitated to say so.

What Dana thought of the three may be judged by his editorial article in the Sun on the day after Greeley’s funeral:

In burying Mr. Greeley we bury the third founder of a newspaper which has become famous and wealthy in this city during the last thirty-five years. Mr. Raymond died three years and Mr. Bennett barely six months ago.

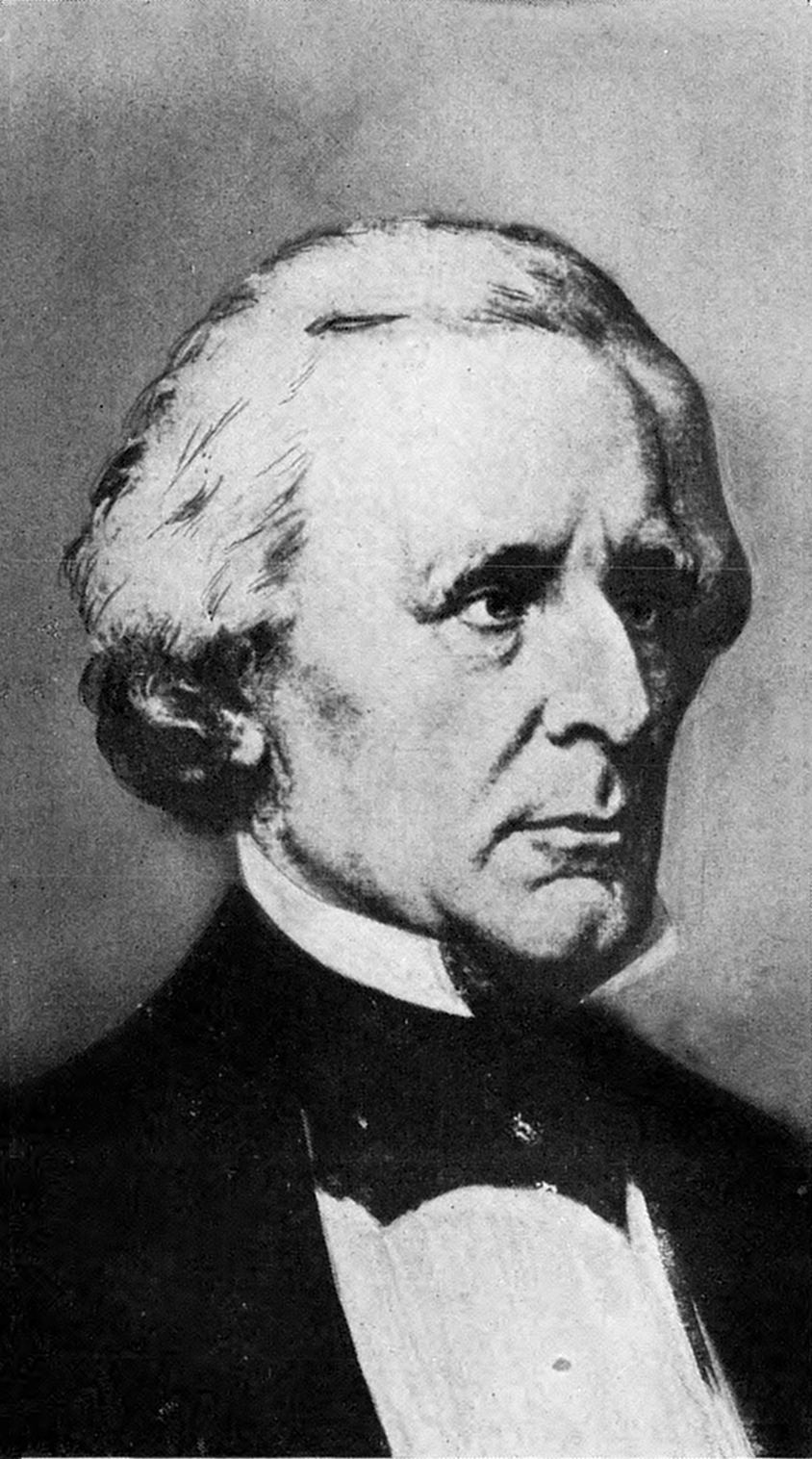

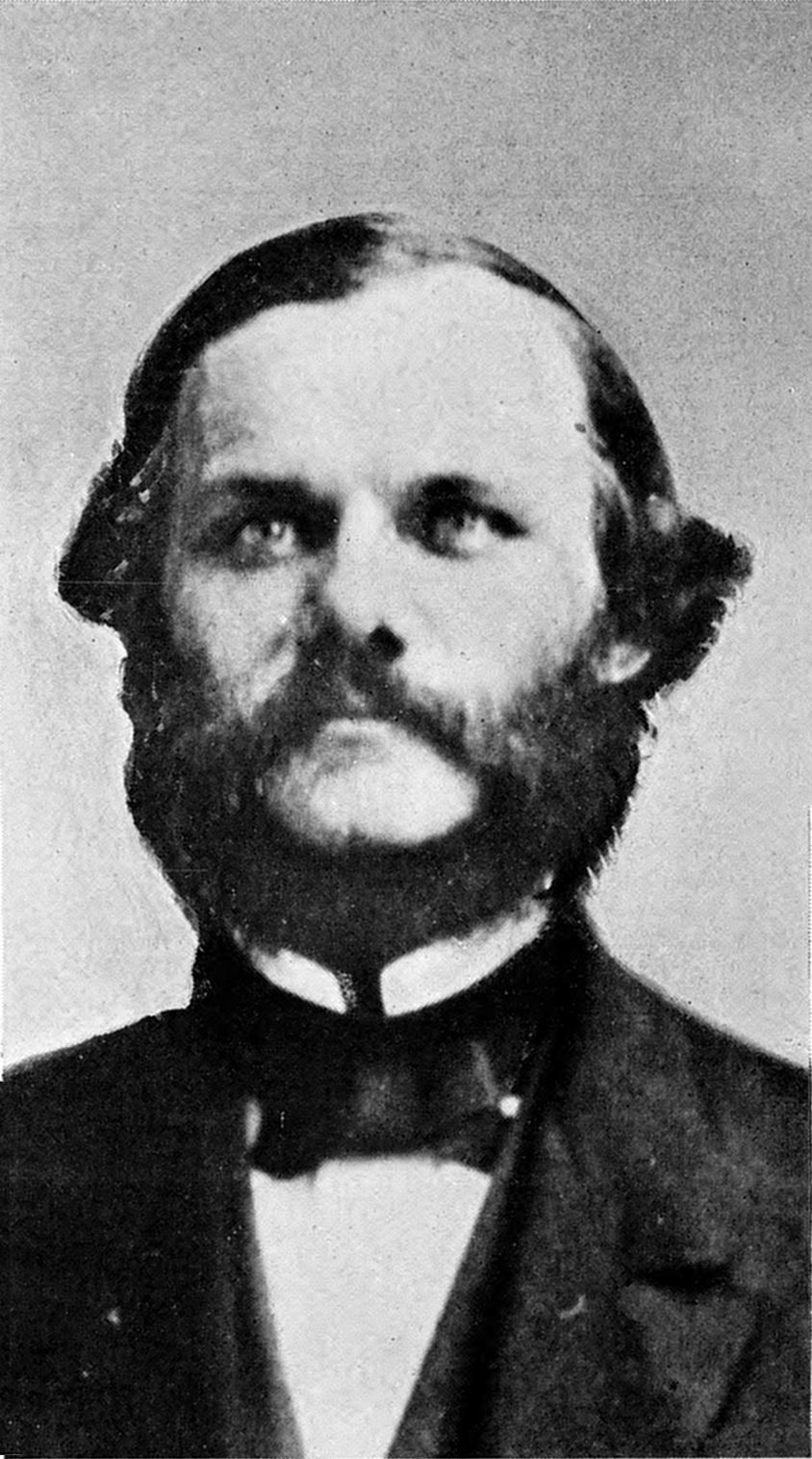

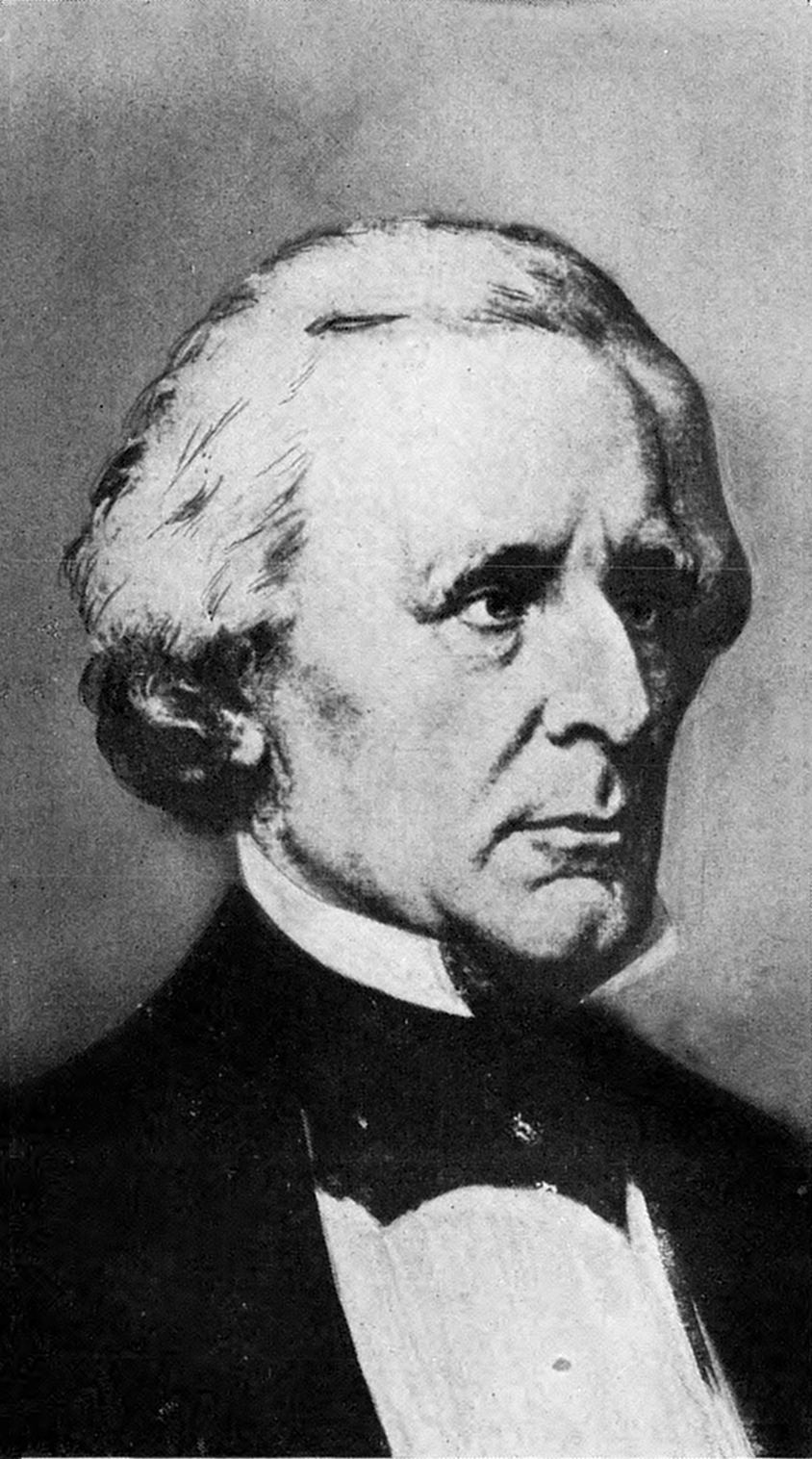

These three men were exceedingly unlike each other, yet each of them possessed extraordinary professional talents. Mr. Raymond surpassed both Mr. Bennett and Mr. Greeley in the versatility of his accomplishments, and in facility and smoothness as a writer. But he was less a journalist than either of the other two. Nature had rather intended him for a lawyer, and success as a legislative debater and presiding officer had directed his ambition toward that kind of life.

Mr. Bennett was exclusively a newspaperman. He was equally great as a writer, a wit, and a purveyor of news; and he never showed any desire to leave a profession in which he had made himself rich and formidable.

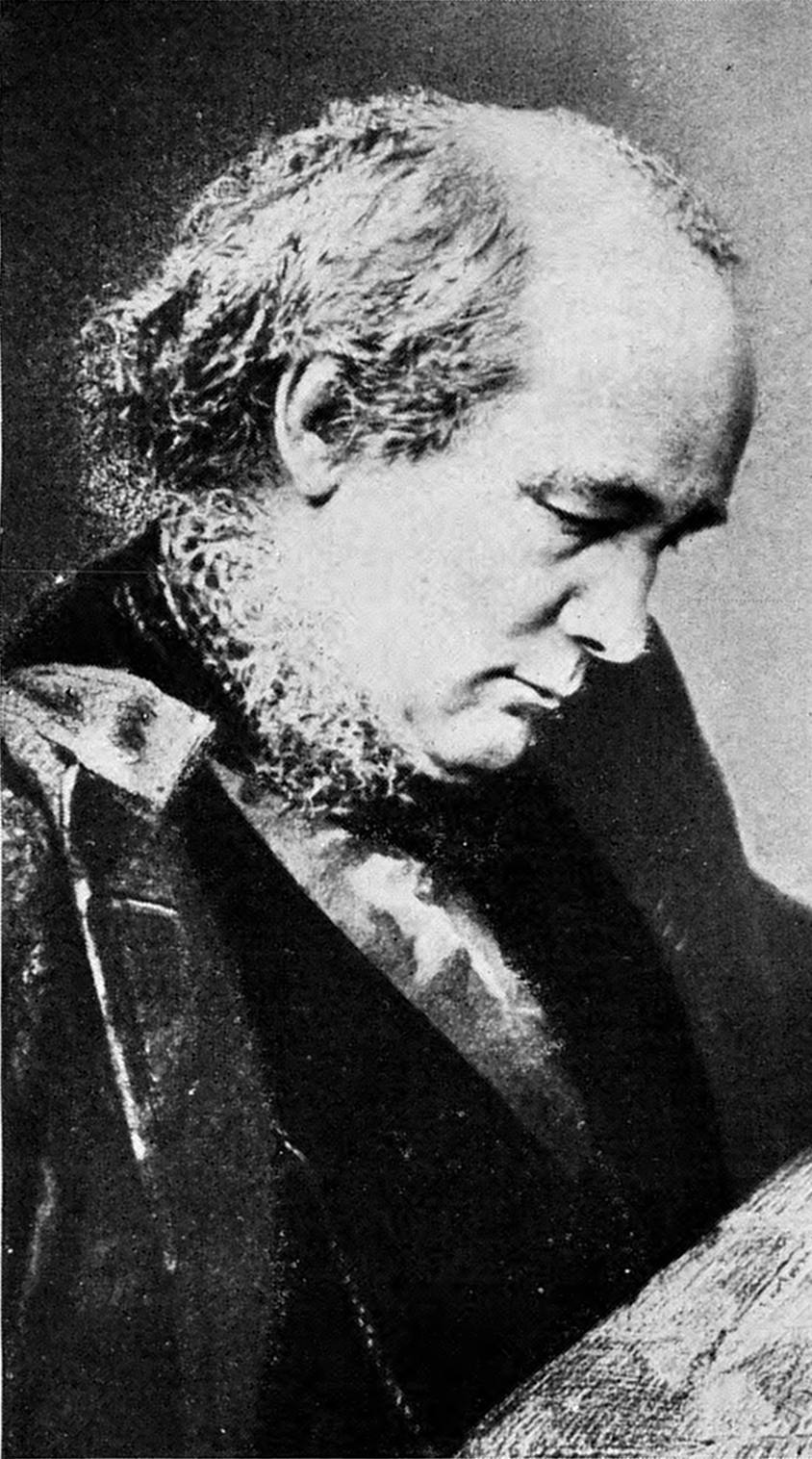

Horace Greeley delighted to be a maker of newspapers, not so much for the thing itself, though to that he was sincerely attached, as for the sake of promoting doctrines, ideas, and theories in which he was a believer; and his personal ambition, which was very profound and never inoperative, made him wish to be Governor, Legislator, Senator, Cabinet Minister, President, because such elevation seemed to afford the clearest possible evidence that he himself was appreciated and that the cause he espoused had gained the hearts of the people. How incomplete, indeed, would be the triumph of any set of principles if their chief advocate and promoter were to go unrecognized and unhonored!

It is a most impressive circumstance that each of these three great journalists has had to die a tragic and pitiable death. One perished by apoplexy long after midnight in the entrance of his own home; another closed his eyes with no relative near him to perform that last sad office; and the third, broken down by toils, excitements, and sufferings too strong to be borne, breathed his last in a private madhouse. What a lesson to the possessors of power, for these three men were powerful beyond others! What a commentary upon human greatness, for they were rich and great, and were looked upon with envy by thousands who thought themselves less fortunate than they! And amid such startling surprises and such a prodigious conflict of lights and shadows, the curtain falls as the tired actor, crowned with long applause, passes from that which seems to that which is.

Louis J. Jennings succeeded Raymond as the editor of the Times, and acted as such until 1876, when he returned to England, his desk being taken by John Foord. Jennings went into politics in England, and was elected a member of Parliament. He also wrote a life of Gladstone and edited a collection of Lord Randolph Churchill’s speeches.

Bennett was followed in the possession of the Herald by his son and namesake. Whitelaw Reid took Greeley’s place at the head of the Tribune. Dana did not like Reid in those days. In a “Survey of Metropolitan Journalism” which appeared in the editorial columns of the Sun on September 3, 1875—the Sun’s forty-second birthday—Dana dismissed his neighbour of the then “tall tower” with—

We pass the Tribune by. Our opinion of it is well known. It is Jay Gould’s paper, and a disgrace to journalism.

Dana’s attitude toward the other big newspapers was more kindly:

The Times is a very respectable paper, and more than that, a journal of which the Republican party has reason to be proud. It is not a servile organ, but a loyal partisan. We prefer for our own part to keep aloof from the party politicians. They are disagreeable fellows to have hanging about a newspaper office, and their advice we do not regard as valuable. But we do not decry party newspapers. They have their field, and must always exist. The Times is a creditable example of such a newspaper. It would be better, however, if Mr. Jennings himself wrote the whole editorial page.

The mistake of the Times was in lapsing into the dulness of respectable conservatism after its Ring fight. It should have kept on and made a crusade against frauds of all sorts.

The Herald has improved since young Mr. Bennett’s return. We are attracted toward this son of his father. He has a passion for manly sports, and that we like. If the shabby writers who make jest of his walking-matches had an income of three or four hundred thousand dollars a year, perhaps they would drive in carriages instead of walking and dawdle away their time on beds of ease or the gorgeous sofas of the Lotos Club. Mr. Bennett does otherwise. He strides up Broadway with the step of an athlete, dons his navy blue and commands his yacht, shoots pigeons, and prefers the open air of Newport to the confinement of the Herald office.

The World is a journal which pleases us on many accounts ... but occasionally there is a bit of prurient wit in its columns that might better be omitted. The World is also too often written in too fantastic language. Its young men seem to vie with each other in tormenting the language. They will do better when they learn that there is more force in simple Anglo-Saxon than in all the words they can manufacture. We advise them to read the Bible and Common Prayer Book. Those books will do their souls good, anyway, and they may also learn to write less affectedly.

The Sun was as frank in discussing its own theories and ambitions as it was in criticising its contemporaries for dulness and poor writing. Dana’s dream, never to be realized, was a newspaper without advertisements. He believed that by getting all the news, condensing it into the smallest readable space, and adding such literary matter as the readers’ tastes demanded, a four-page paper might be produced with a reasonable profit from the sales, after paper and ink, men and machinery, had been paid for.

An editorial article in the Sun on March 13, 1875, was practically a prospectus of this idea:

Until Robert Bonner sagaciously foresaw a handsome profit to be realized by excluding advertisements and crowding a small sheet with such choice literature as would surely attract a mighty throng of readers, never did the owner of any serial publication so much as dream of making both ends meet without a revenue from advertisements. The Tribune, the Times, and the Herald at length ceased to expect a profit from their circulation, and then they came to care for large editions only so far as they served to attract advertisers.

It was then that the Sun conceived the idea of a daily newspaper that should yield more satisfactory dividends from large circulation than had ever been declared by the journals that had looked to the organism of political parties and to enterprising advertisers for the bulk of their income. It saw in New York a city of sufficient population to warrant the experiment of a two-cent newspaper whose cost should equal that of the four-cent dailies in every respect, the cost of white paper alone excepted. Accordingly we produced the Sun on a sheet that leaves a small margin for profit, and by restricting the space allotted to advertisers and eliminating the verbiage in which the eight-page dailies hide the news, we made room in the Sun for not only all the real news of the day, but for interesting literature and current political discussion as well.

It was an enterprise that the public encouraged with avidity. The edition rapidly rose to one hundred and twenty thousand copies daily, and it is now rising; while the small margin of profit on that enormous circulation makes the Sun able to exist without paying any special attention to advertising—approaching very closely, in fact, to the condition of a daily newspaper able to support itself on the profits of its circulation alone.

Only a single further step remains to be taken. That step was recently foreshadowed in a leader in which the Sun intimated that the time was not far distant in which it would reject more advertising than it would accept. With a daily circulation of fifty or a hundred thousand more, there is little doubt that the Sun would find it necessary to limit the advertisers as the reporters and other writers for its columns are limited, each to a space to be determined by the public interest in his subject.

It will be a long stride in the progress of intellectual as distinguished from commercial journalism, and the Sun will probably be the first to make it, thus distancing the successors of Raymond, Bennett, and Greeley in the great sweepstakes for recognition as the Journal of the Future.

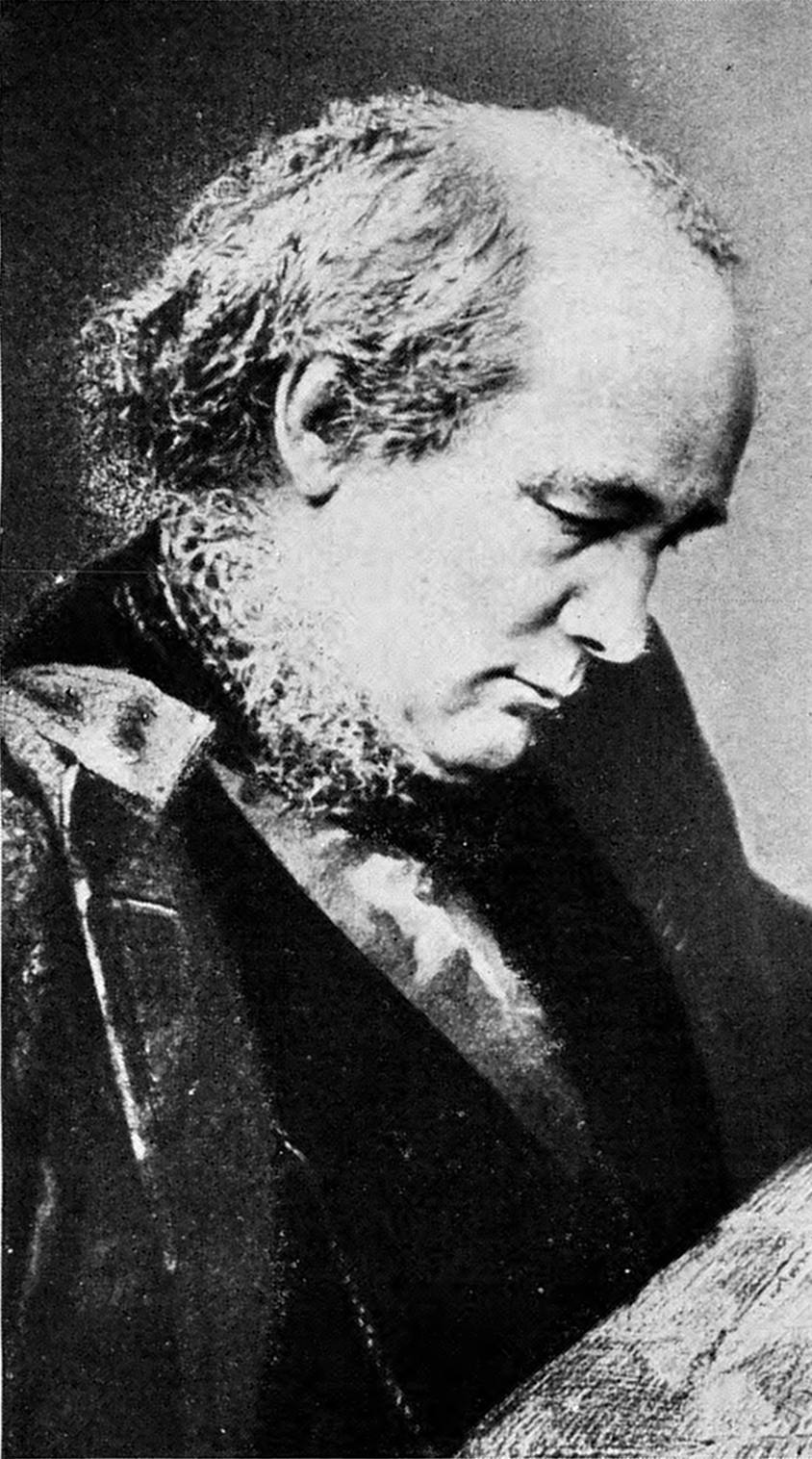

JAMES GORDON BENNETT, SR.

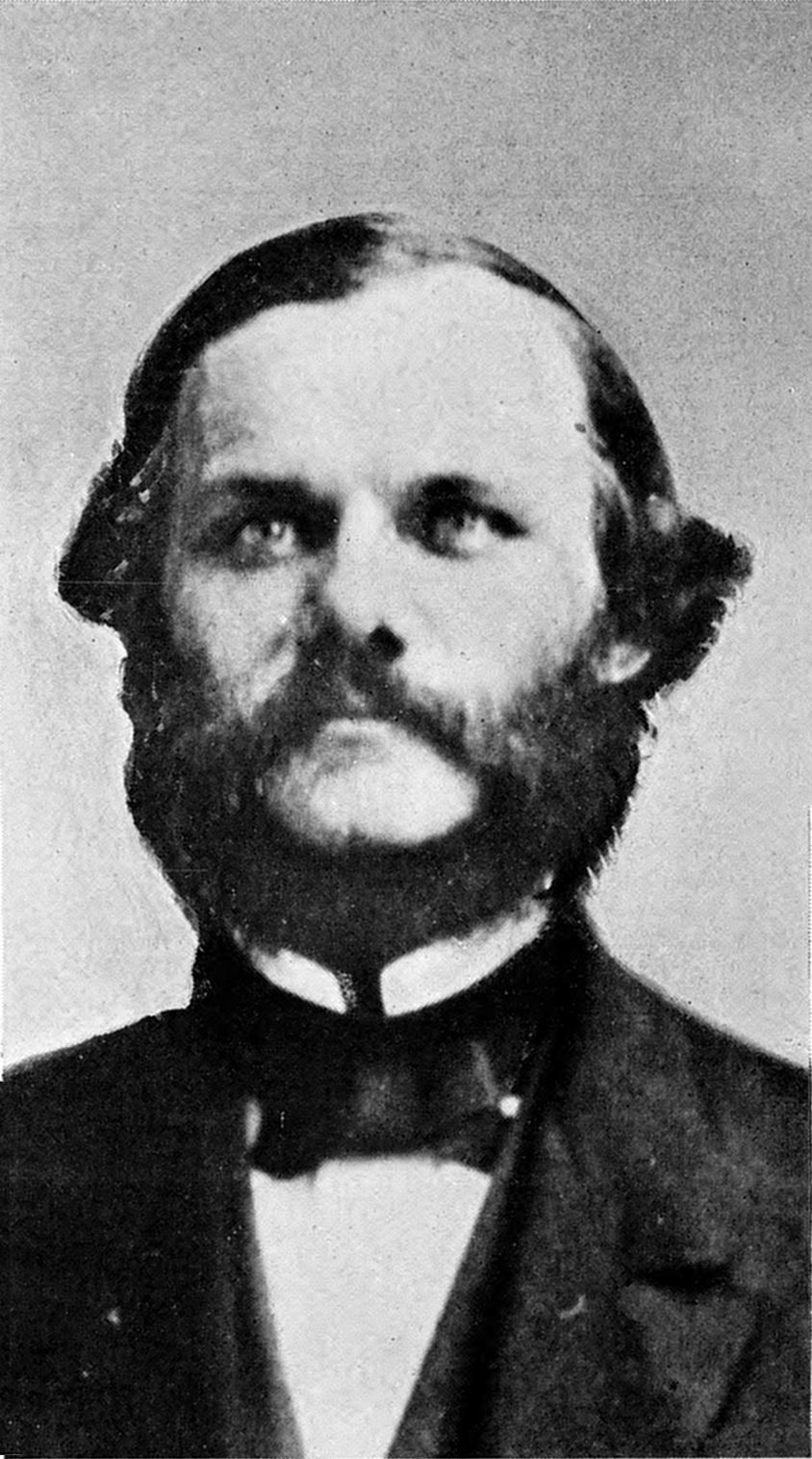

HORACE GREELEY

HENRY J. RAYMOND

It must be remembered, in recalling the failure of Dana’s dream of a paper sans advertising, that his mind was not usually the port of vain dreams. He was a practical man, with more business sense than any other editor of his time, Bennett alone excepted. In him imagination had not swallowed arithmetic, and there is no possible doubt that he had good reason to believe in the practicability of the program he so candidly outlined to his readers. It was part and parcel of his faith in a four-page newspaper—a faith so strong, so well grounded on results, that for the first twenty years of the Dana régime the Sun never appeared in more than four pages, except in emergencies.

In the end, of course, the scheme was beaten by the very excellence of its originator’s qualities. The Sun, by its popularity, drew more and more advertising. By its good English, its freedom from literary shackles, and the spirit of its staff, it attracted more and more writers of distinction, each unwilling to be denied his place in the Sun. Dana always had unlimited space for a good story, just as the cat had an insatiable appetite for a bad one; and thus, through his own genius, he destroyed his own dream, but not without having almost proved that it was possible of realisation.

Dana believed that most of the newspapers of his day—particularly in the seventies—were tiring out not only the reader, but the writer. Commenting on a decline in the newspaper business in the summer of 1875, the Sun said:

Some of our big contemporaries have been overdoing the thing. They seem to think that to secure circulation it is necessary to overload the stomachs of their readers.

The American newspaper-reader demands of an editor that he shall not give him news and discussions in heavy chunks, but so condensed and clarified that he shall be relieved of the necessity of wading through a treatise to get at a fact, or spending time on a dilated essay to get a bite at an argument.

Six or seven dreary columns are filled with leading articles, no matter whether there are subjects to discuss of public interest, or brains at hand to treat them. Our big contemporaries exhaust their young men and drive them too hard. The stock of ideas is not limitless, even in a New York newspaper office.

Another thing has been bad. Men with actual capacity of certain sorts for acceptable writing have been frightened off from doing natural and vigorous work by certain newspaper critics and doctrinaires who are in distress if the literary proprieties are seemingly violated, and if the temper and blood of the writer actually show in his work. They measure our journalistic production by an English standard, which lays it down as its first and most imperative rule that editorial writing shall be free from the characteristics of the writer. This is ruinous to good writing, and damaging to the sincerity of writers.... If we choose to glow or cry out in indignation, we do so, and we are not a bit frightened at the sound of our own voice.

Dana himself had that peculiar faculty, as indescribable as instinct, of knowing, when he saw an article in the paper, just how much work the author of it had put in—particularly in cases where the labour had been in leaving out, rather than in writing. As a result of this intuition he never drove his men. He would accept three lines or three columns for a day’s work, and his admiration might go out more heartily to the three lines. As for the appearance of characteristics in men’s writing, that was as necessary, in Dana’s opinion, as it was wicked in the judgment of the ancient editors.