CHAPTER XII

DANA’S FIRST BIG NEWS MEN

Amos J. Cummings, Dr. Wood, and John B. Bogart.—The Lively Days of Tweedism.—Elihu Root as a Dramatic Critic.—The Birth and Popularity of “The Sun’s” Cat.

MANAGING editors did not come into favour in American newspaper offices until the second half of the last century. As late as 1872 Frederic Hudson, in his “History of Journalism in the United States,” grumbled at the intrusion of a new functionary upon the field:

If a journal has an editor, and editor-in-chief, it is fair to assume that he is also its managing editor.

That historian (he was a Herald man, and Bennett would have no managing editor) had not been reconciled to the fact that between the editor of a newspaper—the director of its policies and opinions and general style and tone—and the subeditors to whose various desks comes the flood of news there must be some one who will act as a link, lightening the labours of the editor and shouldering the responsibilities of the desk men. He may never write an editorial article; may never turn out a sheet of news copy or put a head on an item; may never make up a page or arrange an assignment list—but he must know how to do every one of these things and a great deal more.

A managing editor is really the newspaper’s manager of its employees in the news field. He is an editor to the extent that he edits men. He may appear to spend most of his time and judgment on the acceptance or rejection of news matter, the giving of decisions as to the length or character of an article, its position in the paper, and, more broadly, the general make-up of the next day’s product; but a man might be able to perform all these professional functions wisely and yet be impossible as a managing editor through his inability to handle newspapermen.

The Tribune was the first New York paper to have a managing editor. He was Dana. Serene, tactful, and a man of the world, he was able by judicious handling to keep for the Tribune the services of men like Warren and Pike, who might have been repelled by the sometimes irritable Greeley. The title came from the London Times, where it had been used for years, perhaps borrowed from the directeur gérant of the French newspapers.

The Sun had no managing editor until Dana bought it, Beach having preferred to direct personally all matters above the ken of the city editor. The Sun’s first managing editor was Isaac W. England, whom Dana had known and liked when both were on the Tribune. England was of Welsh blood and English birth, having been born in Twerton, a suburb of Bath, in 1832. He worked at the bookbinding trade until he was seventeen, and then came to the United States and made his living at bookbinding and printing. He used to tell his Sun associates of his triumphal return to England, when he was twenty, for a short visit, which he spent in the shop of his apprenticeship, showing his old master how much better the Yankees were at embossing and lettering.

England returned to America in the steerage and saw the brutal treatment of immigrants. This he described in several articles and sold them to the Tribune. Greeley gave him a job pulling a hand-press at ten dollars a week, but later made him a reporter. He was city editor of the Tribune until after the Civil War, and then he went with his friend Dana to Chicago for the short and profitless experience with the Chicago Republican. In the period between Dana’s retirement from the Republican and his purchase of the Sun, England was manager of the Jersey City Times.

England was managing editor of the Sun only a year, then becoming its publisher—a position for which he was well fitted. An example of his business ability was given in 1877, when Frank Leslie went into bankruptcy. England was made assignee, and he handled the affairs of the Leslie concern so well that its debts were paid off in three years. This was only a side job for England, who continued all the time to manage the business matters of the Sun. When he died, in 1885, Dana wrote that he had “lost the friend of almost a lifetime, a man of unconquerable integrity, true and faithful in all things.”

The second managing editor of the Sun was that great newspaperman Amos Jay Cummings. He was born to newspaper work if any man ever was. His father, who was a Congregational minister—a fact which could not be surmised by listening to Amos in one of his explosive moods—was the editor of the Christian Palladium and Messenger. This staid publication was printed on the first floor of the Cummings home at Irvington, New Jersey. Entrance to the composing-room was forbidden the son, but with tears and tobacco he bribed the printer, one Sylvester Bailey, who set up the Rev. Mr. Cummings’s articles, to let him in through a window. Cummings and Bailey later set type together on the Tribune. They fought in the same regiment in the Civil War. They worked together on the Evening Sun, and they are buried in the same cemetery at Irvington.

The trade once learned, young Amos left home and wandered from State to State, making a living at the case. In 1856, when he was only fourteen, he was attracted by the glamour that surrounded William Walker, the famous filibuster, and joined the forces of that daring young adventurer, who then had control of Nicaragua. The boy was one of a strange horde of soldiers of fortune, which included British soldiers who had been at Sebastopol, Italians who had followed Garibaldi, and Hungarians in whom Kossuth had aroused the martial flame.

Like many of the others in Walker’s army, Cummings believed that the Tennessean was a second Napoleon, with Central America, perhaps South America, for his empire. But when this Napoleon came to his Elba by his surrender to Commander Davis of the United States navy, in the spring of 1857, Cummings decided that there was no marshal’s baton in his own ragged knapsack and went back to be a wandering printer.

Cummings was setting type in the Tribune office when the Civil War began. He hurried out and enlisted as a private in the Twenty-Sixth New Jersey Volunteer Infantry. He fought at Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Fredericksburg. At Marye’s Hill, in the battle of Fredericksburg, his regiment was supporting a battery against a Confederate charge. Their lines were broken and they fell back from the guns. Cummings took the regimental flag from the hands of the colour-sergeant and ran alone, under the enemy’s fire, back to the guns. The Jerseymen rallied, the guns were recovered, and Cummings got the Medal of Honor from Congress. He left the service as sergeant-major of the regiment and presently appeared in Greeley’s office, a seedy figure infolded in an army overcoat.

“Mr. Greeley,” said Amos, “I’ve just got to have work.”

“Oh, indeed!” creaked Horace. “And why have you got to have work?”

Cummings said nothing, but turned his back on the great editor, lifted his coat-tails and showed the sad, if not shocking, state of his breeches. He got work. In 1863, when the Tribune office was threatened by the rioters, Amos helped to barricade the composing-room and save it from the mob.

Cummings served as editor of the Weekly Tribune and as a political writer for the daily. This is the way he came to quit the Tribune:

John Russell Young, the third managing editor of the Tribune, got the habit of issuing numbered orders. Two of these orders reached Cummings’s desk, as follows:

Order No. 756—There is too much profanity in this office.

Order No. 757—Hereafter the political reporter must have his copy in at 10.30 P.M.

Cummings turned to his desk and wrote:

Order No. 1234567—Everybody knows —— well that I get most of the political news out of the Albany Journal, and everybody knows —— —— well that the Journal doesn’t get here until eleven o’clock at night, and anybody who knows anything knows —— —— well that asking me to get my stuff up at half past ten is like asking a man to sit on a window-sill and dance on the roof at the same time.

CUMMINGS.

The result of this multiplicity of numbered orders was that shortly afterward Cummings presented himself to the editor of the Sun.

“Why are you leaving the Tribune?” asked Mr. Dana.

“They say,” replied Amos, “that I swear too much.”

“Just the man for me!” replied Dana, according to the version which Cummings used to tell.

At any rate, Amos went on the Sun as managing editor, and he continued to swear. The compositors now in the Sun office who remember him at all remember him largely for that.

The union once set apart a day for contributions to the printers’-home fund, and each compositor was to contribute the fruits of a thousand ems of composition. Cummings, who was proud of being a union printer, left his managing-editor’s desk and went to the composing-room.

“Ah, Mr. Cummings,” said Abe Masters, the foreman, “I’ll give you some of your own copy to set.”

“To hell with my own copy!” said Cummings, who knew his handwriting faults. “Give me some reprint.”

Green reporters got a taste of the Cummings profanity. One of them put a French phrase in a story. Cummings asked him what it meant, and the youth told him.

“Then why the hell didn’t you write it that way?” yelled Cummings. “This paper is for people who read English!”

In those days murderers were executed in the old Tombs prison in Centre Street. Cummings, who was full of enterprise, sought a way to get quickly the fall of the drop. The telephone had not been perfected, but there was a shot-tower north of the Sun’s office and east of the Tombs. Cummings sent one man to the Tombs, with instructions to wave a flag upon the instant of the execution. Another man, stationed at the top of the shot-tower, had another flag, with which he was to make a sign to Cummings on the roof of the Sun Building, as soon as he saw the flag move at the prison.

The reporter at the Tombs arranged with a keeper to notify him just before the execution, but the keeper was sent on an errand, and presently Cummings, standing nervously on the roof of the Sun Building, heard the newsboys crying the extras of a rival sheet. The plan had fallen through. No blanks could adequately represent the Cummings temper upon that occasion.

Cummings was probably the best all-round news man of his day. He had the executive ability and the knowledge of men that make a good managing editor. He knew what Dana knew—that the newspapers had yet to touch public sympathy and imagination in the news columns as well as in editorial articles; and he knew how to do it, how to teach men to do it, how to cram the moving picture of a living city into the four pages of the Sun. He advised desk men, complimented or corrected reporters, edited local articles, and, when a story appealed to him strongly, he went out and got it and wrote it himself.

In such brief biographies of Cummings as have been printed you will find that he is best remembered in the outer world as a managing editor, or as the editor of the Evening Sun, or as a Representative in Congress fighting for the rights of Civil War veterans, printers’ unions, and letter-carriers; but among the oldest generation of newspapermen he is revered as a great reporter. He was the first real human-interest reporter. He knew the news value of the steer loose in the streets, the lost child in the police station, the Italian murder that was really a case of vendetta. The Sun men of his time followed his lead, and a few of them, like Julian Ralph, outdid him, but he was the pioneer; and a thousand Sun men since then have kept, or tried to keep, on the Cummings trail.

It was Cummings who sent men to cover the police stations at night and made it possible for the Sun to beat the news association on the trivial items which were the delight of the reader, and which helped, among other things, to shoot the paper’s daily circulation to one hundred thousand in the third year of the Dana ownership.

The years when Cummings was managing editor of the Sun were years stuffed with news. Even a newspaperman without imagination would have found plenty of happenings at hand. The Franco-Prussian War, the gold conspiracy that ended in Black Friday (September 24, 1869), the Orange riot (July 12, 1871), the great Chicago fire, the killing of Fisk by Stokes, Tweedism—what more could a newspaperman wish in so brief a period? And, of course, always there were murders. There were so many mysterious murders in the Sun that a suspicious person might have harboured the thought that Cummings went out after his day’s work was done and committed them for art’s sake.

When men and women stopped killing, Cummings would turn to politics. Tweed was the great man then; under suspicion, even before 1870, but a great man, particularly among his own. The Sun printed pages about Tweed and his satellites and the great balls of the Americus Club, their politico-social organisation. It described the jewels worn by the leaders of Tammany Hall, including the two-thousand-dollar club badge—the head of a tiger with eyes of ruby and three large diamonds shining above them.

Everybody who wanted the political news read the Sun. As Jim Fisk remarked one evening as he stood proudly with Jay Gould in the lobby of the Grand Opera House—proud of his notoriety in connection with the Erie Railroad jobbery, proud of the infamy he enjoyed from the fact that he owned two houses in the same block in West Twenty-third Street, housing his wife in one and Josie Mansfield in the other; proud of his guilty partnership in Tweedism—

“The Sun’s a lively paper. I can never wait for daylight for a copy. I have my man down there with a horse every morning, and just as soon as he gets a Sun hot from the press he jumps on the back of that horse and puts for me as if all hell was after him.

“Gould’s the same way; he has to see it before daylight, too. My man has to bring him up a copy. You always get the news ahead of everybody else. Why, the first news I got that Gould and me were blackballed in the Blossom Club we got from the Sun. I’m damned if I’d believe it at first, and Gould says, ‘What is this Blossom Club?’ Just then Sweeny came in. I asked Sweeny if it was true, and Sweeny said yes, that Tweed was the man that done it all. There it was in the Sun, straight’s a die.”

The Sun reporter who chronicled this—it may have been Cummings himself—had gone to ask Fisk whether he and his friends had hired a thug to black-jack the respectable Mr. Dorman B. Eaton, a foe of the Erie outfit; but he took down and printed Fisk’s tribute to the Sun’s enterprise. As there was scarcely a morning in those days when the Sun did not turn up some new trick played by the Tweed gang and the Erie group, their anxiety to get an early copy was natural.

Tweed and his philanthropic pretences did not deceive the Sun. On February 24, 1870—a year and a half before the exposure which sent the boss to prison—the Sun printed an editorial article announcing that Tweed was willing to surrender his ownership of the city upon the following terms:

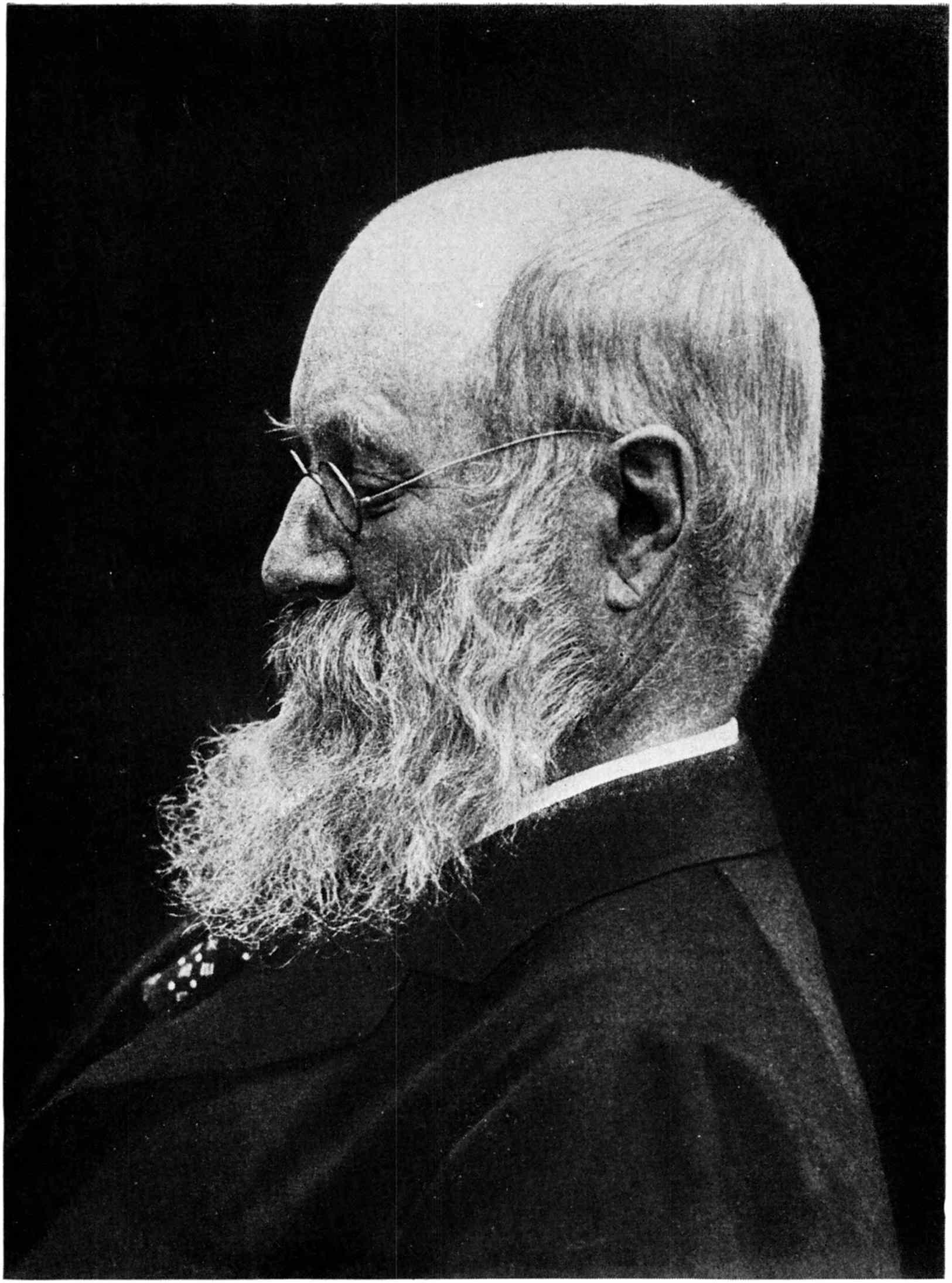

(From a Photograph by Paul Dana)

MR. DANA AT SEVENTY

To give up all interest in the court-house swindle.

To receive no more revenue from the department of survey and inspection of buildings; and he hopes the people of New York will remember his generosity in giving up this place, inasmuch as his share amounts to over one hundred thousand dollars a year.

Tweed was liked by many New Yorkers, particularly those who knew him only by his lavish charities. One of these wrote the following letter, which the Sun printed on December 7, 1870, under the heading “A Monument to Boss Tweed—the Money Paid In”:

Enclosed please find ten cents as a contribution to erect a statue to William M. Tweed on Tweed Plaza. I have no doubt that fifty thousand to seventy-five thousand of his admirers will contribute. Yours, etc.,

SEVENTEENTH WARD VOTER.

On December 12 the Sun said editorially:

Has Boss Tweed any friends? If he has, they are a mean set. It is now more than a week since an appeal was made to them to come forward and put up the ancillary qualities to erect a statue of Mr. Tweed in the centre of Tweed Plaza; but as yet only four citizens have sent in their subscriptions. These were not large, but they were paid in cash, and there is reason for the belief that they were the tokens of sincere admiration for Mr. Tweed. But the hundreds, or, rather, thousands, of small-potato politicians whom he has made rich and powerful stand aloof and do not offer a picayune.

We propose that the statue shall be executed by Captain Albertus de Groot, who made the celebrated Vanderbilt bronzes, but we have not yet decided whether it shall represent the favorite son of New York afoot or ahorseback. In fact, we rather incline to have a nautical statue, exhibiting Boss Tweed as a bold mariner, amid the wild fury of a hurricane, splicing the main brace in the foretopgallant futtock shrouds of his steam-yacht. But that is a matter for future consideration. The first thing is to get the money; and if those who claim to be Mr. Tweed’s friends don’t raise it, we shall begin to believe the rumor that the Hon. P. Brains Sweeny has turned against him, and has forbidden every one to give anything toward the erection of the projected statue.

Ten days later the Sun carried on the editorial page a long news story headed “Our Statue of Boss Tweed—the Readers of the Sun Going to Work in Dead Earnest—The Sun’s Advice Followed, Ha! Ha!—Organisation of the Tweed Testimonial Association of the City of New York—A Bronze Statue Worth Twenty-Five Thousand Dollars to Be Erected.”

Sure enough, the ward politicians had taken the joke seriously. Police Justice Edward J. Shandley, Tim Campbell, Coroner Patrick Keenan, Police Commissioner Smith, and a dozen other faithful Tammany men were on the list of trustees. They decided upon the space then known as Tweed Plaza, at the junction of East Broadway and New Canal and Rutgers Streets as the site for the monument.

The Sun added to the joke by printing more letters from contributors. One, from Patrick Maloy, “champion eel-bobber,” brought ten cents and the suggestion that the statue should be inscribed with the amount of money that Tweed had made out of the city. This sort of thing went on into the new year, the Sun aggravating the movement with grave editorial advice.

At last the jest became more than Tweed could bear, and from his desk in the Senate Chamber at Albany, on March 13, 1871, he sent the following letter to Judge Shandley, the chairman of the statue committee:

MY DEAR SIR:

I learn that a movement to erect a statue to me in the city of New York is being seriously pushed by a committee of citizens of which you are chairman.

I was aware that a newspaper of our city had brought forward the proposition, but I considered it one of the jocose sensations for which that journal is so famous. Since I left the city to engage in legislation the proposition appears to have been taken up by my friends, no doubt in resentment at the supposed unfriendly motive of the original proposition and the manner in which it had been urged.

The only effect of the proposed statue is to present me to the public as assenting to the parade of a public and permanent testimonial to vanity and self-glorification which do not exist. You will thus perceive that the movement, which originated in a joke, but which you have made serious, is doing me an injustice and an injury; and I beg of you to see to it that it is at once stopped.

I hardly know which is the more absurd—the original proposition or the grave comments of others, based upon the idea that I have given the movement countenance. I have been about as much abused as any man in public life; I can stand abuse and bear even more than my share; but I have never yet been charged with being deficient in common sense.

Yours very truly,

WM. M. TWEED.

This letter appeared in the Sun the next day under the facetious heading: “A Great Man’s Modesty—The Most Remarkable Letter Ever Written by the Noble Benefactor of the People.” Editorial regret was expressed at Tweed’s declination; and, still in solemn mockery, the Sun grieved over the return to the subscribers of the several thousand dollars that had been sent to Shandley’s committee. William J. Florence, the comedian, had put himself down for five hundred dollars.

Was it utterly absurd that the Tweed idolaters should have taken seriously the Sun’s little joke? No, for so serious a writer as Gustavus Myers wrote in his “History of Tammany Hall” (1901) that “one of the signers of the circular has assured the author that it was a serious proposal. The attitude of the Sun confirms this.” And another grave literary man, Dr. Henry Van Dyke, set this down in his “Essays on Application” (1908):

William M. Tweed, of New York, who reigned over the city for seven years, stole six million dollars or more for himself and six million dollars or more for his followers; was indorsed at the heights of his corruption by six of the richest citizens of the metropolis; had a public statue offered to him by the New York Sun as a “noble benefactor of the city,” etc.

Of course Mr. Myers and Dr. Van Dyke had never read the statue articles from beginning to end, else they would not have stumbled over the brick that even Tweed, with all his conceit, was able to perceive.

In July, 1871, when the New York Times was fortunate enough to have put in its hands the proof of what everybody already suspected—that Senator Tweed, Comptroller Connolly, Park Commissioner Sweeny, and their associates were plundering the city—the Sun was busy with its own pet news and political articles, the investigation of the Orange riots and the extravagance and nepotism of President Grant’s administration.

The Sun did not like the Times, which had been directed, since the death of Henry J. Raymond, in 1869, by Raymond’s partner, George Jones, and Raymond’s chief editorial writer, Louis J. Jennings; but the Sun liked the Tweed gang still less. It had been pounding at it for two years, using the head-lines “Boss Tweed’s Legislature,” or “Mr. Sweeny’s Legislature,” every day of the sessions at the State capital; but neither the Sun nor any other newspaper had been able to obtain the figures that proved the robbery until the county bookkeeper, Matthew J. O’Rourke, dug them out and took them to the Times.

The books showed that the city had been gouged out of five million dollars in one item alone—the price paid in two years to a Tweed contracting firm, Ingersoll & Co., for furniture and carpets for the county court-house. Enough carpets had been bought—or at least paid for—to cover the eight acres of City Hall Park three layers deep. And that five million dollars was only a fraction of the loot.

In September, 1871, after the mass-meeting of citizens in Cooper Union, the Sun began printing the revelations of Tweedism under the standing head, “The Doom of the Ring.”

Tweed engaged as counsel, among others, William O. Bartlett, who was not only counsel for the Sun but, next to Mr. Dana, the paper’s leading editorial writer at that time. The boss may have fancied that in retaining Bartlett he retained the Sun, but it is more likely that he sought Bartlett’s services because of that lawyer’s reputation as an aggressive and able counsellor. If Tweed had any delusions about influencing the Sun, they were quickly dispelled. On September 18, in an editorial article probably written by Dana, the Sun said:

While Mr. Bartlett, in his able argument before Judge Barnard on Friday, vindicated Mr. Tweed from certain allegations set forth in the complaint of Mr. Foley, he by no means relieved him from all complicity in the enormous frauds and robberies that have been committed in the government of this city. With all his ability, that is something beyond Mr. Bartlett’s power; and it is vain to hope that either of the leaders of the Tammany Ring can ever regain the confidence of the public, or for any length of time exercise the authority of political office. They must all go, Sweeny, Tweed, and Hall, as well as Connolly.

Mr. Tweed must not imagine that he can buy his way out of the present complication with money, as he did in 1870. The next Legislature will be made up of different material from the Republicans he purchased, and the people will exercise a sterner supervision over its acts.

A good picture of Tweed’s popularity, which he still retained among his own people, was drawn in an editorial article in the Sun of October 30, 1871, three days after the boss had been arrested and released in a million dollars’ bail:

In the Fourth District William M. Tweed is sure to be re-elected [to the State Senate]. The Republican factions, after a great deal of quarreling, have concentrated on O’Donovan Rossa, a well-known Fenian, but his chance is nothing. Even if it had been possible by beginning in season to defeat Tweed, it cannot be done with only a week’s time.

Besides, his power there is absolute. The district comprises the most ignorant and most vicious portion of the city. It is full of low grog-shops, houses of ill-fame, low gambling-houses, and sailor boarding-houses, whose keepers enjoy protection and immunity, for which they pay by the most efficient electioneering services. Moreover, the district is full of sinecures paid from the city treasury. If, instead of having stolen millions, Mr. Tweed were accused of a dozen murders, or if, instead of being in human form, he wore the semblance of a bull or a bear, the voters of the Fourth District would march to the polls and vote for him just as zealously as they will do now, and the inspectors of election would furnish for him by fraudulent counting any majority that might be thought necessary in addition to the votes really given.

Tweed was re-elected to the State Senate by twelve thousand plurality.

The great robber-boss was a source of news from his rise in the late sixties to his death in 1878. As early as March, 1870, the Sun gave its readers an intimate idea of Tweed’s private extravagances under the heading: “Bill Tweed’s Big Barn—Democratic Extravagance Versus That of the White House—Grant’s Billiard Saloon, Caligula’s Stable, and Leonard Jerome’s Private Theatre Eclipsed—Martin Van Buren’s Gold Spoons Nowhere—Belmont’s Four-in-Hand Overshadowed—a Picture for Rural Democrats.”

Beneath this head was a column story beginning:

The Hon. William M. Tweed resides at 41 West Thirty-sixth Street. The Hon. William M. Tweed’s horses reside in East Fortieth Street, between Madison and Park Avenues.

That was the Sun’s characteristic way of starting a story.

Tweed was, in a way, responsible for the appearance of a Sun more than four pages in size. Up to December, 1875, there was no issue of the Sun on Sundays. In November of that year it was announced that beginning on December 5 there would be a Sunday Sun, to be sold at three cents, one cent more than the week-day price, but nothing was said, or thought, of an increase In size.

On Saturday, December 4, Tweed, with the connivance of his keepers, escaped from his house in Madison Avenue. This made a four-column story on which Mr. Dana had not counted. Also, the advertisers had taken advantage of the new Sunday issue, and there were more than two pages of advertisements. There was nothing for it but to make an eight-page paper, for which Dana, who then believed that all the news could be told in a folio, apologised as follows:

We confess ourselves surprised at the extraordinary pressure of advertisements upon our pages this morning; and disappointed in being compelled to present the Sun to our readers in a different form from that to which they are accustomed. We trust, however, that they will find it no less interesting than usual; and, still more, that they will feel that although the appearance may be somewhat different, it is yet the same friendly and faithful Sun.

But the Sunday issue of the Sun never went back to four pages, for the eight-page paper had been made so attractive with special stories, reprint, and short fiction that both readers and advertisers were pleased. It was ten years, however, before the week-day