CHAPTER I

SUNRISE AT 222 WILLIAM STREET

Benjamin H. Day, with No Capital Except Youth and Courage, Establishes the First Permanent Penny Newspaper.—The Curious First Number Entirely His Own Work.

IN the early thirties of last century the only newspapers in the city of New York were six-cent journals whose reading-matter was adapted to the politics of men, and whose only appeal to women was their size, perfectly suited to deep pantry-shelves.

Dave Ramsey, a compositor on one of these sixpennies, the Journal of Commerce, had an obsession. It was that a penny paper, to be called the Sun, would be a success in a city full of persons whose interest was in humanity in general, rather than in politics, and whose pantry-shelves were of negligible width. Why his mind fastened on the Sun as the name of this child of his vision is not known; perhaps it was because there was a daily in London bearing that title. It was a short name, easily written, easily spoken, easily remembered.

Benjamin H. Day, another printer, worked beside Dave Ramsey in 1830. Ramsey reiterated his idea to his neighbour so often that Day came to believe in it, although it is doubtful whether he had the great faith that possessed Ramsey. Now that due credit has been given to Ramsey for the idea of the penny Sun, he passes out of the record, for he never attempted to put his project into execution.

Nor was Day’s enthusiasm for a penny Sun so big that he plunged into it at once. He was a business man rather than a visionary. With the savings from his wages as a compositor he went into the job-printing business in a small way. He still met his old chums and still talked of the Sun, but it is likely that he never would have come to start it if it had not been for the cholera.

There was an epidemic of this plague in New York in 1832. It killed more than thirty-five hundred people in that year, and added to the depression of business already caused by financial disturbances and a wretched banking system. The job-printing trade suffered with other industries, and Day decided that he needed a newspaper—not to reform, not to uplift, not to arouse, but to push the printing business of Benjamin H. Day. Incidentally he might add lustre to the fame of the President, Andrew Jackson, or uphold the hands of the mayor of New York, Gideon Lee; but his prime purpose was to get the work of printing handbills for John Smith, the grocer, or letter-heads for Richard Robinson, the dealer in hay. Incidentally he might become rich and powerful, but for the time being he needed work at his trade.

Ben Day was only twenty-three years old. He was the son of Henry Day, a hatter of West Springfield, Massachusetts, and Mary Ely Day; and sixth in descent from his first American ancestor, Robert Day. Shortly after the establishment of the Springfield Republican by Samuel Bowles, in 1824, young Day went into the office of that paper, then a weekly, to learn the printer’s trade. That was two years before the birth of the second and greater Samuel Bowles, who was later to make the Republican, as a daily, one of the greatest of American newspapers.

BENJAMIN H. DAY

A Bust in the Possession of Mrs. Florence A. Snyder, Summit, N. J.

Day learned well his trade from Sam Bowles. When he was twenty, and a first-class compositor, he went to New York, and worked at the case in the offices of the Evening Post and the Commercial Advertiser. He married, when he was twenty-one, Miss Eveline Shepard. At the time of the Sun’s founding Mr. Day lived, with his wife and their infant son, Henry, at 75 Duane Street, only a few blocks from the newspaper offices.

Day was a good-looking young man with a round, calm, resolute face. He possessed health, industry, and character. Also he had courage, for a man with a family was taking no small risk in launching, without capital, a paper to be sold at one cent.

The idea of a penny paper was not new. In Philadelphia, the Cent had had a brief, inglorious existence. In Boston, the Bostonian had failed to attract the cultured readers of the modern Athens. Eight months before Day’s hour arrived the Morning Post had braved it in New York, selling first at two cents and later at one cent, but even with Horace Greeley as one of the founders it lasted only three weeks.

When Ben Day sounded his friends, particularly the printers, as to their opinion of his project, they cited the doleful fate of the other penny journals. He drew, or had designed, a head-line for the Sun that was to be, and took it about to his cronies. A. S. Abell, a printer on the Mercantile Advertiser, poked the most fun at him. A penny paper, indeed! But this same Abell lived to stop scoffing, to found another Sun—this one in Baltimore—and to buy a half-million-dollar estate out of the profits of it. He was the second beneficiary of the penny Sun idea.

William M. Swain, another journeyman printer, also made light of Day’s ambition. He lived to be Day’s foreman, and later to own the Philadelphia Public Ledger. He told Day that the penny Sun would ruin him. As Day had not much enthusiasm at the outset, surely his friends did not add to it, unless by kindling his stubbornness.

As for capital, he had none at all, in the money sense. He did have a printing-press, hardly improved from the machine of Benjamin Franklin’s day, some job-paper, and plenty of type. The press would throw off two hundred impressions an hour at full speed, man power. He hired a room, twelve by sixteen feet, in the building at 222 William Street. That building was still there, in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge approach, when the Sun celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1883; but a modern six-story envelope factory is on the site to-day.

There is no question as to the general authorship of the first paper. Day was proprietor, publisher, editor, chief pressman, and mailing-clerk. He was not a lazy man. He stayed up all the night before that fateful Tuesday, September 3, 1833, setting with his own hands some advertisements that were regularly appearing in the six-cent papers, for he wanted to make a show of prosperity.

He also wrote, or clipped from some out-of-town newspaper, a poem that would fill nearly a column. He rewrote news items from the West and South—some of them not more than a month old. As for the snappy local news of the day, he bought, in the small hours of that Tuesday morning, a copy of the Courier and Enquirer, the livest of the six-cent papers, took it to the single room in William Street, clipped out or rewrote the police-court items, and set them up himself. A boy, whose name is unknown to fame, assisted him at devil’s work. A journeyman printer, Parmlee, helped with the press when the last quoin had been made tight in the fourth and last of the little pages.

The sun was well up in the sky before its namesake of New York came slowly, hesitatingly, almost sadly, up over the horizon of journalism—never to set! In the years to follow, the Sun was to have changes in ownership, in policy, in size, and in style, but no week-day was to come when it could not shine. Of all the morning newspapers printed in New York on that 3rd of September, 1833, there is only one other—the Journal of Commerce—left.

But young Mr. Day, wiping the ink from his hands at noon, and waiting in doubt to see whether the public would buy the thousand Suns he had printed, could not foresee this. Neither could he know that, by this humble effort to exalt his printing business, he had driven a knife into the sclerotic heart of ancient journalism. The sixpenny papers were to laugh at this tiny intruder—to laugh and laugh, and to die.

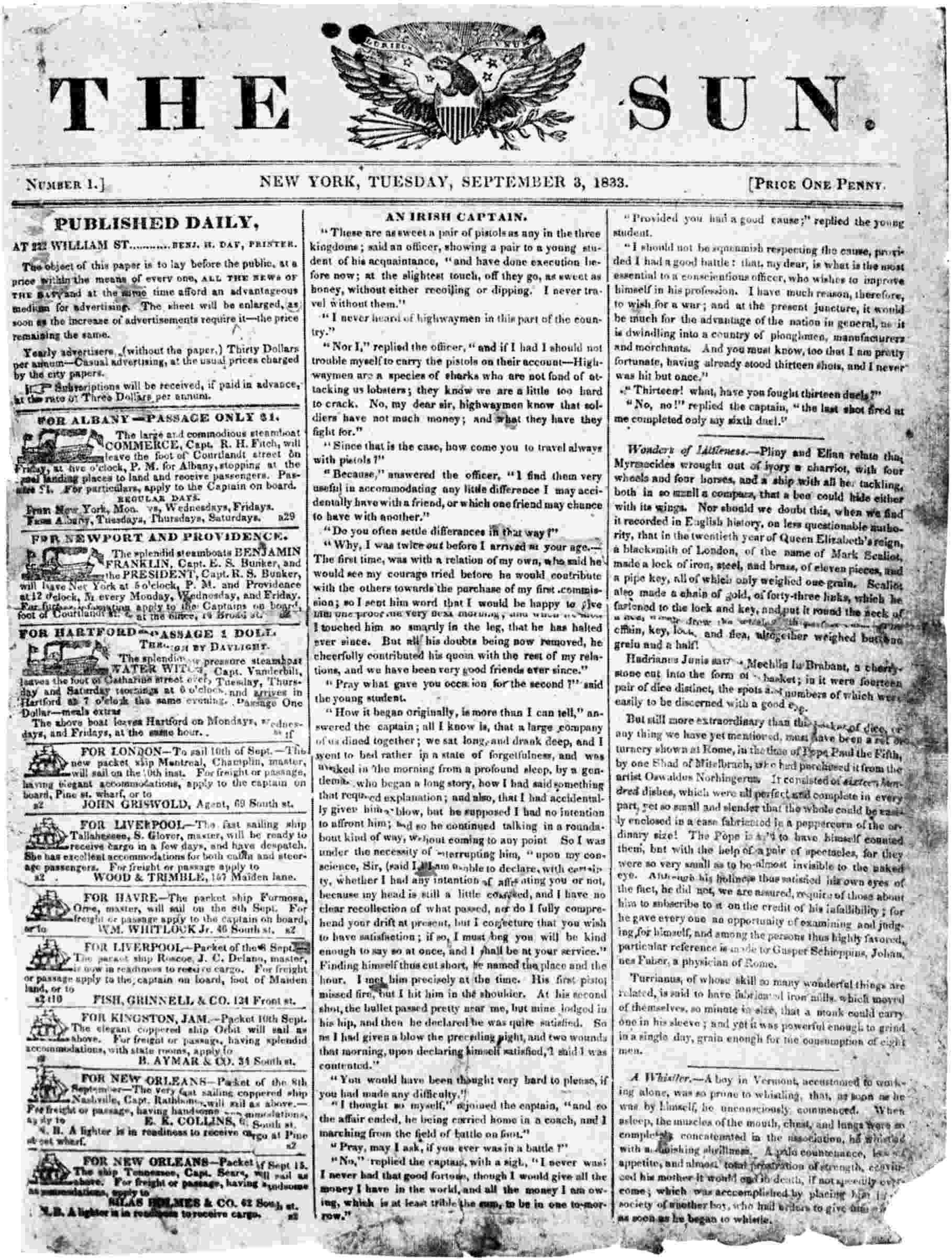

The size of the first Sun was eleven and one-quarter by eight inches, not a great deal bigger than a sheet of commercial letter paper, and considerably less than one-quarter the size of a page of the Sun of to-day. Compared with the first Sun, the present newspaper is about sixteen times larger. The type was a good, plain face of agate, with some verse on the last page in nonpareil.

An almost perfect reprint of the first Sun was issued as a supplement to the paper on its twentieth birthday, in 1853, and again—to the number of about one hundred and sixty thousand copies—on its fiftieth birthday, in 1883. Many of the persons who treasure the replicas of 1883 believe them to be original first numbers, as they were not labelled “Presented gratuitously to the subscribers of the Sun,” as was the issue of 1853. Hardly a month passes by but the Sun receives one of them from some proud owner. It is easy, however, to tell the reprint from the original, for Mr. Day in his haste committed an error at the masthead of the editorial or second page of the first number. The date-line there reads “September 3, 1832,” while in the reprints it is “September 3, 1833,” as it should have been, but wasn’t, in the original. And there are minor typographical differences, invisible to the layman.

Of the thousand, or fewer, copies of the first Sun, only five are known to exist—one in the bound file of the Sun’s first year, held jealously in the Sun’s safe; one in the private library of the editor of the Sun, Edward Page Mitchell; one in the Public Library at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street, New York; and two in the library of the American Type Founders Company, Jersey City.

There were three columns on each of the four pages. At the top of the first column on the front page was a modest announcement of the Sun’s ambitions:

The object of this paper is to lay before the public, at a price within the means of every one, ALL THE NEWS OF THE DAY, and at the same time afford an advantageous medium for advertising.

It was added that the subscription in advance was three dollars a year, and that yearly advertisers were to be accommodated with ten lines every day for thirty dollars per annum—ten cents a day, or one cent a line. That was the old fashion of advertising. The friendly merchant bought thirty dollars’ worth of space, say in December, and inserted an advertisement of his fur coats or snow-shovels. The same advertisement might be in the paper the following July, for the newspapers made no effort to coordinate the needs of the seller and the buyer. So long as the merchant kept his name regularly in print, he felt that was enough.

The leading article on the first page was a semi-humorous story about an Irish captain and his duels. It was flanked by a piece of reprint concerning microscopic carved toys. There was a paragraph about a Vermont boy so addicted to whistling that he fell ill of it. Mr. Day’s apprentice may have needed this warning.

The front-page advertising, culled from other newspapers and printed for effect, consisted of the notices of steamship sailings. In one of these Commodore Vanderbilt offered to carry passengers from New York to Hartford, by daylight, for one dollar, on his splendid low-pressure steamboat Water Witch. Cornelius Vanderbilt was then thirty-nine years old, and had made the boat line between New York and New Brunswick, New Jersey, pay him forty thousand dollars a year. When the Sun started, the commodore was at the height of his activity, and he stuck to the water for thirty years afterward, until he had accumulated something like forty million dollars.

E. K. Collins had not yet established his famous Dramatic line of clipper-ships between New York and Liverpool, but he advertised the “very fast sailing coppered ship Nashville for New Orleans.” He was only thirty then.

Cooks were advertised for by private families living in Broadway, near Canal Street—pretty far up-town to live at that day—and in Temple Street, near Liberty, pretty far down-town now.

On the second page was a bit of real news, the melancholy suicide of a young Bostonian of “engaging manners and amiable disposition,” in Webb’s Congress Hall, a hotel. There were also two local anecdotes; a paragraph to the effect that “the city is nearly full of strangers from all parts of this country and Europe”; nine police-court items, nearly all concerning trivial assaults; news of murders committed in Florida, at Easton, Pennsylvania, and at Columbus, Ohio; a report of an earthquake at Charlottesville, Virginia, and a few lines of stray news from Mexico.

The third page had the arrivals and clearances at the port of New York, a joke about the cholera in New Orleans, a line to say that the same disease had appeared in the City of Mexico, an item about an insurrection in the Ohio penitentiary, a marriage announcement, a death notice, some ship and auction advertisements, and the offer of a reward of one thousand dollars for the recovery of thirteen thousand six hundred dollars stolen from the mail stage between Boston and Lynn and the arrest of the thieves.

The last page carried a poem, “A Noon Scene,” but the atmosphere was of the Elysian Fields over in Hoboken rather than of midday in the city. When Day scissored it, probably he did so with the idea that it would fill a column. Another good filler was the bank-note table, copied from a six-cent contemporary. The quotations indicated that not much of the bank currency of the day was accepted at par.

The rest of the page was filled with borrowed advertising. The Globe Insurance Company, of which John Jacob Astor was a director, announced that it had a capital of a million dollars. The North River Insurance Company, whose directorate included William B. Astor, declared its willingness to insure against fire and against “loss or damage by inland navigation.” At that time the boilers of river steamboats had an unpleasant trick of blowing up; hence Commodore Vanderbilt’s mention of the low pressure of the Water Witch. John A. Dix, then Secretary of State of the State of New York, and later to be the hero of the “shoot him on the spot” order, advertised an election. Castleton House Academy, on Staten Island, offered to teach and board young gentlemen at twenty-five dollars a quarter.

THE FIRST ISSUE OF “THE SUN”

Such was the first Sun. Part of it was stale news, rewritten. Part was borrowed advertising. It is doubtful whether even the police-court items were original, although they were the most human things in the issue, the most likely to appeal to the readers whom Day hoped to reach—people to whom the purchase of a paper at six cents was impossible, and to whom windy, monotonous political discussions were a bore.

In those early thirties, daily journalism had not advanced very far. Men were willing, but means and methods were weak. The first English daily was the Courrant, issued in 1702. The Orange Postman, put out the following year, was the first penny paper. The London Times was not started until 1785. It was the first English paper to use a steam press, as the Sun was the first American paper.

The first American daily was the Pennsylvania Packet, called later the General Advertiser, begun in Philadelphia in 1784. It died in 1837. Of the existing New York papers only the Globe dates back to the eighteenth century, having been founded in 1797 as the Commercial Advertiser. Next to it in age is the Evening Post, started in 1801.

The weakness of the early dailies was largely due to the fact that their publishers looked almost entirely to advertising for the support of the papers. On the other hand, the editors were politicians or highbrows who thought more of a speech by Lord Piccadilly on empire than of a good street tragedy; more of an essay by Lady Geraldine Glue than of a first-class report of a kidnapping.

Another great obstacle to success—one for which neither editor nor publisher was responsible—was the lack of facilities for the transmission of news. Fulton launched the Clermont twenty-six years before Day launched the Sun, but even in Day’s time steamships were nothing to brag of, and the first of them was yet to cross the Atlantic. When the Sun was born, the most important railroad in America was thirty-four miles long, from Bordentown to South Amboy, New Jersey. There was no telegraph, and the mails were of pre-historic slowness.

It was hard to get out a successful daily newspaper without daily news. A weekly would have sufficed for the information that came in, by sailing ship and stage, from Europe and Washington and Boston. Ben Day was the first man to reconcile himself to an almost impossible situation. He did so by the simple method of using what news was nearest at hand—the incidental happenings of New York life. In this way he solved his own problem and the people’s, for they found that the local items in the Sun were just what they wanted, while the price of the paper suited them well.