CHAPTER II

THE FIELD OF THE LITTLE “SUN”

A Very Small Metropolis Which Day and His Partner, Wisner, Awoke by Printing Small Human Pieces About Small Human Beings and Having Boys Cry the Paper.

HOW far could the little Sun hope to cast its beam in a stodgy if not naughty world? The circulation of all the dailies in New York at the time was less than thirty thousand. The seven morning and four evening papers, all sold at six cents a copy, shared the field thus:

MORNING PAPERS

|

Morning Courier and New York Enquirer

|

4,500

|

|

Democratic Chronicle

|

4,000

|

|

New York Standard

|

2,400

|

|

New York Journal of Commerce

|

2,300

|

|

New York Gazette and General Advertiser

|

1,500

|

|

New York Daily Advertiser

|

1,400

|

|

Mercantile Advertiser and New York Advocate

|

1,200

|

EVENING PAPERS

|

Evening Post

|

3,000

|

|

Evening Star

|

2,500

|

|

New York Commercial Advertiser

|

2,100

|

|

New York American

|

1,600

|

|

Total

|

26,500

|

New York was the American metropolis, but it was of about the present size of Indianapolis or Seattle. Of its quarter of a million population, only eight or ten thousand lived above Twenty-third Street. Washington Square, now the residence district farthest down-town, had just been adopted as a park; before that it had been the Potter’s Field. In 1833 rich New Yorkers were putting up some fine residences there—of which a good many still stand. Sixth Street had had its name changed to Waverley Place in honor of Walter Scott, recently dead, the literary king of the day.

Wall Street was already the financial centre, with its Merchants’ Exchange, banks, brokers, and insurance companies. Canal Street was pretty well filled with retail stores. Third Avenue had been macadamized from the Bowery to Harlem. The down-town streets were paved, and some were lighted with gas at seven dollars a thousand cubic feet.

Columbia College, in the square bounded by Murray, Barclay, Church, and Chapel Streets, had a hundred students; now it has more than a hundred hundred. James Kent was professor of law in the Columbia of that day, and Charles Anthon was professor of Greek and Latin. A rival seat of learning, the University of the City of New York, chartered two years earlier, was temporarily housed at 12 Chambers Street, with a certain Samuel F. B. Morse as professor of sculpture and painting. There were twelve schools, harbouring six thousand pupils, whose welfare was guarded by the Public School Society of New York, Lindley Murray secretary. The National Academy of Design, incorporated five years before, guided the budding artist in Clinton Hall, and Mr. Morse was its president, while it had for its professor of mythology one William Cullen Bryant.

Albert Gallatin was president of the National Bank, at 13 Wall Street. Often at the end of his day’s work he would walk around to the small shop in William Street where his young friend Delmonico, the confectioner, was trying to interest the gourmets of the city in his French cooking. Gideon Lee, besides being mayor, was president of the Leather Manufacturers’ Bank at 334 Pearl Street. He was the last mayor of New York to be appointed by the common council, for Dix’s advertisement in the first Sun called an election by which the people of the city gained the right to elect a mayor by popular vote.

A list of the solid citizens of the New York of that year would include Peter Schermerhorn, Nicholas Fish, Robert Lenox, Sheppard Knapp, Samuel Swartwout, Henry Beekman, Henry Delafield, John Mason, William Paulding, David S. Kennedy, Jacob Lorillard, David Lydig, Seth Grosvenor, Elisha Riggs, John Delafield, Peter A. Jay, C. V. S. Roosevelt, Robert Ray, Preserved Fish, Morris Ketchum, Rufus Prime, Philip Hone, William Vail, Gilbert Coutant, and Mortimer Livingston.

These men and their fellows ran the banks and the big business of that day. They read the six-cent papers, mostly those which warned the public that Andrew Jackson was driving the country to the devil. It would be years before the Sun would bring the light of common, everyday things into their dignified lives—if it ever did so. Day, the printer, did not look to them to read his paper, although he hoped for some small part of their advertising. It is likely that one of the Gouverneurs—Samuel L.—read the early Sun, but he was postmaster, and it was his duty to examine new and therefore suspicionable publications.

Incidentally, Postmaster Gouverneur had one clerk to sort all the mail that came into the city from the rest of the world. It was a small New York upon which the timid Sun cast its still smaller beams. The mass of the people had not been interested in newspapers, because the newspapers brought nothing into their lives but the drone of American and foreign politics. A majority of them were in sympathy with Tammany Hall, particularly since 1821, when the property qualification was removed from the franchise through Democratic effort.

New York had literary publications other than the six-cent papers. The Knickerbocker Magazine was founded in January of 1833, with Charles Hoffman, assistant editor of the American Magazine, as editor. Among the contributors engaged were William Cullen Bryant and James K. Paulding. The subscription-list, it was proudly announced, had no fewer than eight hundred names on it. The Mechanics’ Magazine, the Sporting Magazine, the American Ploughboy, the Journal of Public Morals, and the Youth’s Temperance Lecturer were among the periodicals that contended for public favour.

Bryant was a busy man, for he was the chief editor of the Evening Post as well as a magazine contributor and a teacher. Fame had come to him early, for “Thanatopsis” was published when he was twenty-three, and “To a Water-fowl” appeared a year later, in 1818. Now, in his thirties, he was no longer the delicate youth, the dreamy poet. One April day in 1831 Bryant and William L. Stone, one of the editors of the Commercial Advertiser, had a rare fight in front of the City Hall, the poet beginning it with a cowskin whip swung at Stone’s head, and the spectators ending it after Stone had seized the whip. These two were editors of sixpenny “respectables.”

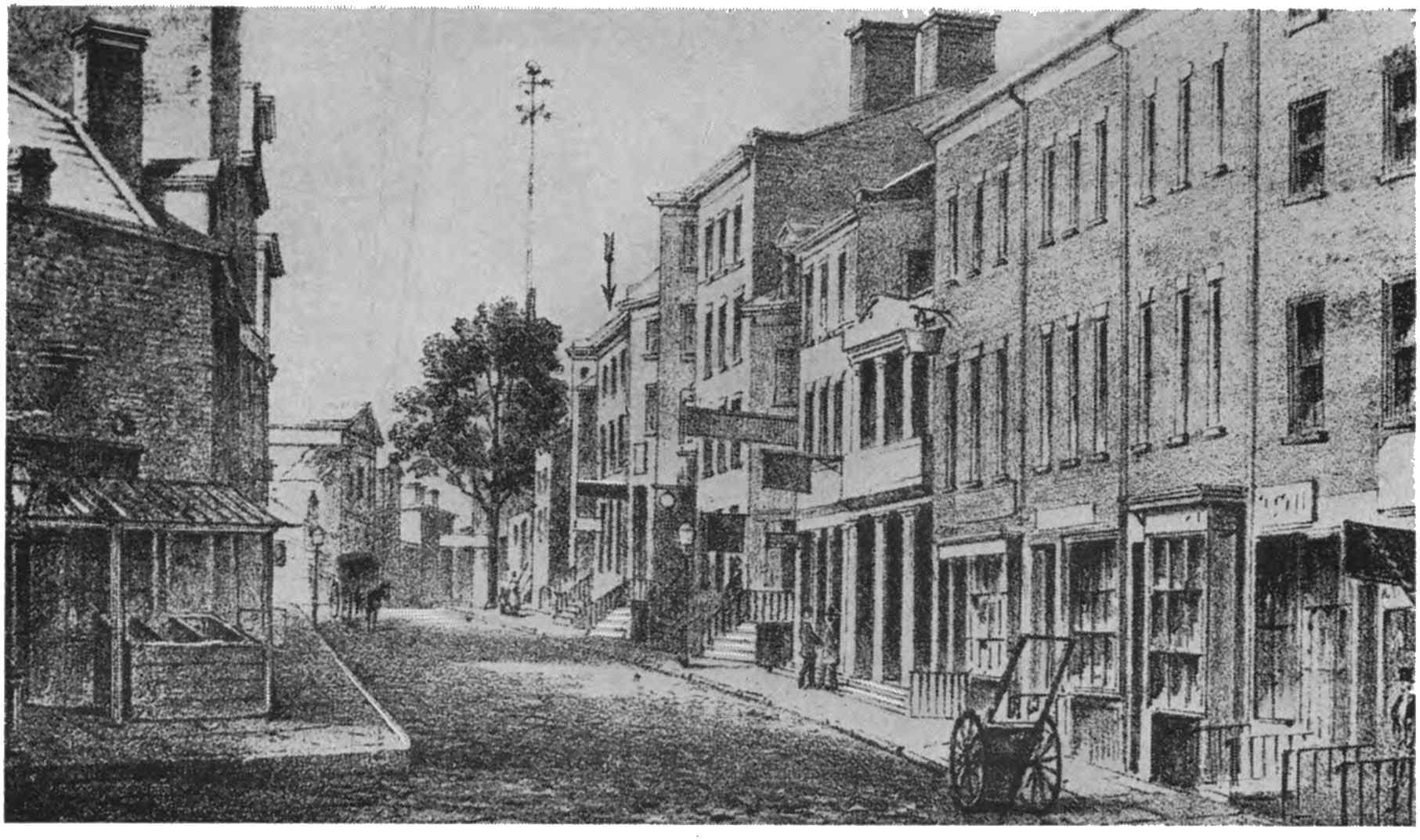

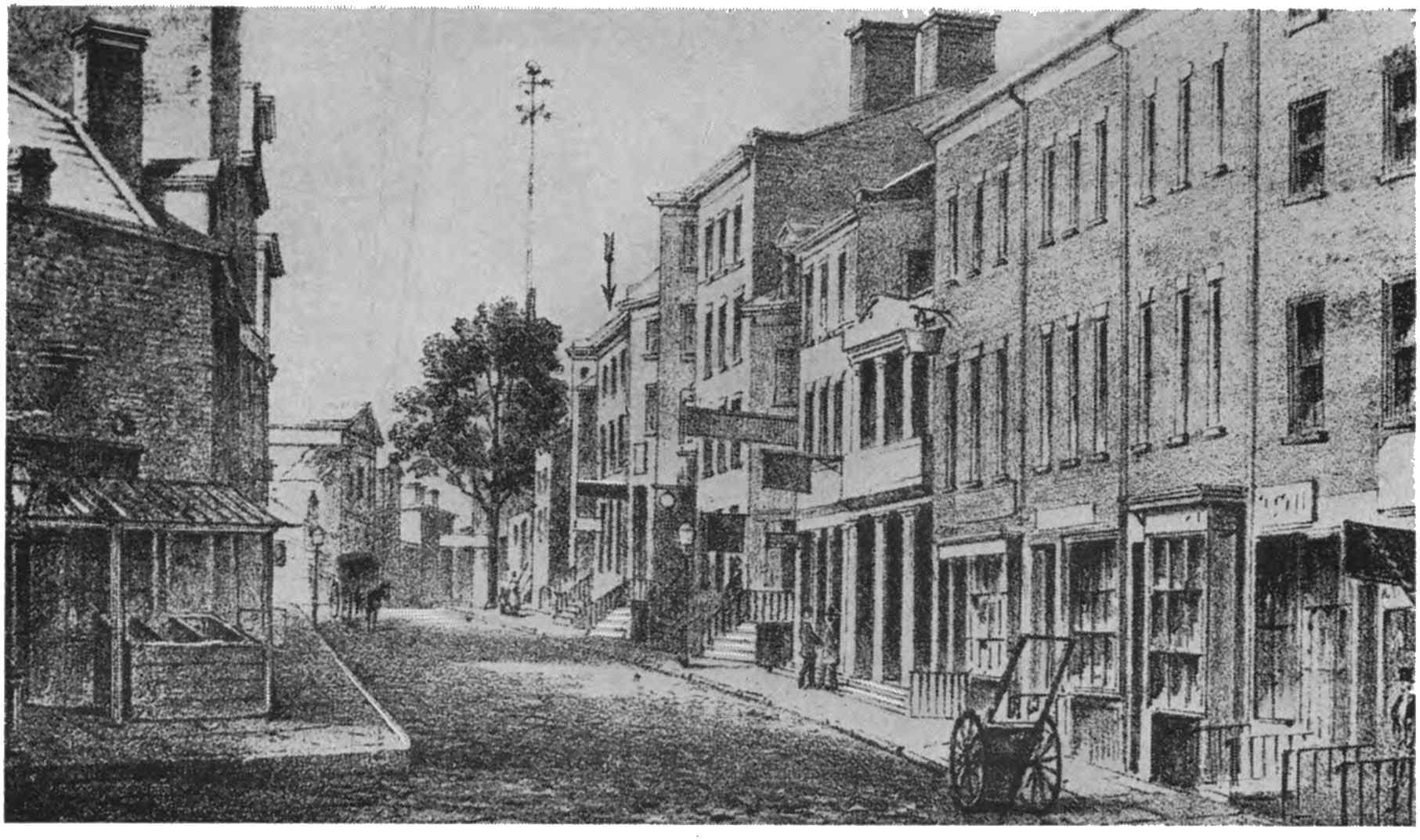

THE FIRST HOME OF “THE SUN,” 222 WILLIAM STREET

(Under the Arrow)

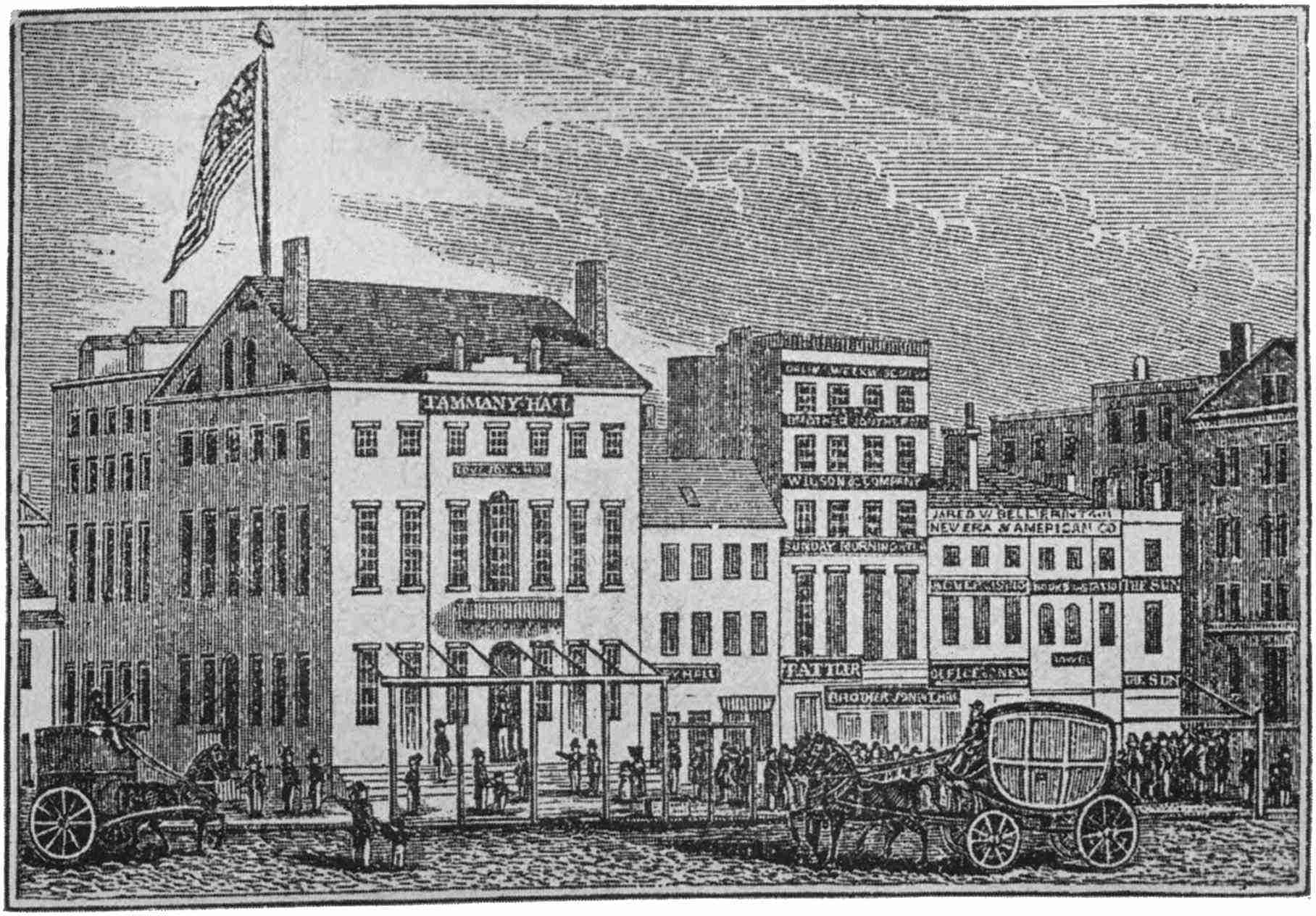

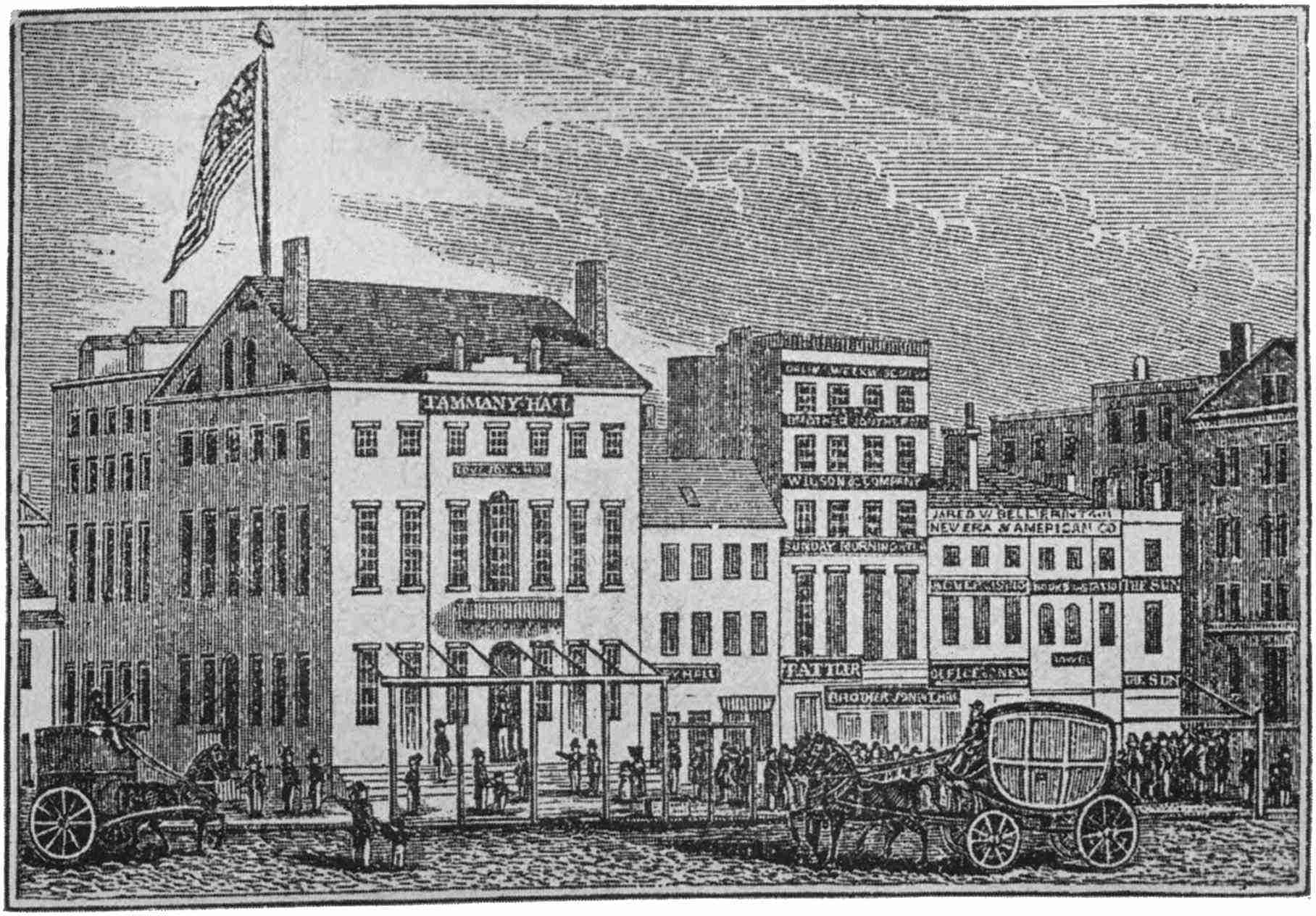

THE SECOND HOME OF “THE SUN”

Nassau Street, from Frankfort to Spruce, in the Early Forties. “The Sun’s” Second Home Is Shown at the Right End of the Block. The Tammany Hall Building Became “The Sun’s” Fourth Home in 1868.

Irving and Cooper, Bryant and Halleck, Nathaniel P. Willis and George P. Morris were the largest figures of intellectual New York. In 1833 Irving returned from Europe after a visit that had lasted seventeen years. He was then fifty, and had written his best books. Cooper, half a dozen years younger, had long since basked in the glory that came to him with the publication of “The Spy,” “The Pilot,” and “The Last of the Mohicans.” He and Irving were guests at every cultured function.

Prescott was finishing his first work, “The History of Ferdinand and Isabella.” Bancroft was beginning his “History of the United States.” George Ticknor had written his “Life of Lafayette.” Hawthorne had published only “Fanshawe” and some of the “Twice Told Tales.” Poe was struggling along in Baltimore. Holmes, a medical student, had written a few poems. Dr. John William Draper, later to write his great “History of the Intellectual Development of Europe,” arrived from Liverpool that year to make New York his home.

Longfellow was professor of modern languages at Bowdoin, and unknown to fame as a poet. Whittier had written “Legends of New England” and “Moll Pitcher.” Emerson was in England. Richard Henry Dana and Motley were at Harvard. Thoreau was helping his father to make lead-pencils. Parkman, Lowell, and Herman Melville were schoolboys.

Away off in Buffalo was a boy of fourteen who clerked in his uncle’s general store by day, selling steel traps to Seneca braves, and by night read Latin, Greek, poetry, history, and the speeches of Andrew Jackson. His name was Charles Anderson Dana.

The leading newspaperman of the day in New York was James Watson Webb, a son of the General Webb who held the Bible upon which Washington took the oath of office as first President. J. Watson Webb had been in the army and, as a journalist, was never for peace at any price. He united the Morning Courier and the Enquirer, and established a daily horse express between New York and Washington, which is said to have cost seventy-five hundred dollars a month, in order to get news from Congress and the White House twenty-four hours before his rivals.

Webb was famed as a fighter. He had a row with Duff Green in Washington in 1830. In January, 1836, he thrashed James Gordon Bennett in Wall Street. He incited a mob to drive Wood, a singer, from the stage of the Park Theater. In 1838 he sent a challenge to Representative Cilley, of Maine, a classmate of Longfellow and Hawthorne at Bowdoin. Cilley refused to fight, on the ground that he had made no personal reflections on Webb’s character; whereupon Representative Graves, of Kentucky, who carried the card for Webb, challenged Cilley for himself, as was the custom. They fought with rifles on the Annapolis Road, and Cilley was killed at the third shot.

In 1842 Webb fought a duel with Representative Marshall, of Kentucky, and not only was wounded, but on his return to New York was sentenced to two years in prison “for leaving the State with the intention of giving or receiving a challenge.” At the end of two weeks, however, he was pardoned.

Having deserted Jackson and become a Whig, Webb continued to own and edit the Courier and Enquirer until 1861, when it was merged with the World. His quarrels, all of political origin, brought prestige to his paper. Ben Day had no duelling-pistols. His only chance to advertise the Sun was by its own light and its popular price.

Beyond Webb, Day had no lively journalist with whom to contend at the outset, and Webb probably did not dream that the Sun would be worthy of a joust. Perhaps fortunately for Day, Horace Greeley had just failed in his attempt to run a one-cent paper. This was the Morning Post, which Greeley started in January, 1833, with Francis V. Story, a fellow printer, as his partner, and with a capital of one hundred and fifty dollars. It ran for three weeks only.

Greeley and Story still had some type, bought on credit, and they issued a tri-weekly, the Constitutionalist, which, in spite of its dignified title, was the avowed organ of the lotteries. Its columns contained the following card:

Greeley & Story, No. 54 Liberty Street, New York, respectfully solicit the patronage of the public to their business of letterpress printing, particularly lottery-printing, such as schemes, periodicals, and so forth, which will be executed on favorable terms.

It must be remembered that at that time lotteries were not under a cloud. There were in New York forty-five lottery offices, licensed at two hundred and fifty dollars apiece annually, and the proceeds were divided between the public schools and a home for deaf-mutes. That was the last year of legalized lotteries. After they disappeared Greeley started the New Yorker, the best literary weekly of its time. It was not until April, 1841, that he founded the Tribune.

Doubtless there were many young New Yorkers of that period who would have made bang-up reporters, but apparently, until Day’s time, with few exceptions they did not work on morning newspapers. One exception was James Gordon Bennett, whose work for Webb on the Courier and Enquirer helped to make it the leading American paper.

Nathaniel P. Willis and George P. Morris would probably have been good reporters, for they knew New York and had excellent styles, but they insisted on being poets. With Morris it was not a hollow vocation, for the author of “Woodman, Spare That Tree,” could always get fifty dollars for a song. He and Willis ran the Mirror and later the New Mirror, and wrote verse and other fanciful stuff by the bushel. Philip Hone would have been the best reporter in New York, as his diary reveals, but he was of the aristocracy, and he seems to have scorned newspapermen, particularly Webb and Bennett.

But somehow, by that chance which seemed to smile on the Sun, Ben Day got clever reporters. He wanted one to do the police-court work, for he saw, from the first day of the paper, that that was the kind of stuff that his readers devoured. To them the details of a beating administered by James Hawkins to his wife were of more import than Jackson’s assaults on the United States Bank.

When George W. Wisner, a young printer who was out of work, applied to the Sun for a job, Day told him that he would give him four dollars a week if he would get up early every day and attend the police-court, which held its sessions from 4 A.M. on. The people of the city were quite as human then as they are to-day. Unregenerate mortals got drunk and fought in the streets. Others stole shoes. The worst of all beat their wives. Wisner was to be the Balzac of the daybreak court in a year when Balzac himself was writing his “Droll Stories.”

The second issue of the Sun continued the typographical error of the day before. The year in the date-line of the second page was “1832.” The big news in this paper was under date of Plymouth, England, August 1, and it told of the capture of Lisbon by Admiral Napier on the 25th of July. Day—or perhaps it was Wisner—wrote an editorial article about it:

To us as Americans there can be little of interest in the triumph of one member of a royal family of Europe over another; and although we can but rejoice at the downfall of the modern Nero who so lately filled the Portuguese throne, yet if rumor speak the truth the victorious Pedro is no better than he should be.

The editor lamented the general lack of news:

With the exception of the interesting news from Portugal there appears to be very little worthy of note. Nullification has blown over; the President’s tour has terminated; Black Hawk has gone home; the new race for President is not yet commenced, and everything seems settled down into a calm. Dull times, these, for us newspaper-makers. We wish the President or Major Downing or some other distinguished individual would happen along again and afford us material for a daily article. Or even if the sea-serpent would be so kind as to pay us a visit, we should be extremely obliged to him and would honor his snakeship with a most tremendous puff.

Theatrical advertising appeared in this number, the Park Theater announcing the comedy of “Rip Van Winkle,” as redramatized by Mr. Hackett, who played Rip. Mr. Gale was playing “Mazeppa” at the Bowery. Perhaps these advertisements were borrowed from a six-cent paper, but there was one “help wanted” advertisement that was not borrowed. It was the upshot of Day’s own idea, destined to bring another revolution in newspaper methods:

TO THE UNEMPLOYED—A number of steady men can find employment by vending this paper. A liberal discount is allowed to those who buy to sell again.

Before that day there had been no newsboys; no papers were sold in the streets. The big, blanket political organs that masqueraded as newspapers were either sold over the counter or delivered by carriers to the homes of the subscribers. Most of the publishers considered it undignified even to angle for new subscribers, and one of them boasted that his great circulation of perhaps two thousand had come unsolicited.

The first unemployed person to apply for a job selling Suns in the streets was a ten-year-old-boy, Bernard Flaherty, born in Cork. Years afterward two continents knew him as Barney Williams, Irish comedian, hero of “The Emerald Ring,” and “The Connie Soogah,” and at one time manager of Wallack’s old Broadway Theatre.

When Day got some regular subscribers, he sent carriers on routes. He charged them sixty-seven cents a hundred, cash, or seventy-five cents on credit. The first of these carriers was Sam Messenger, who delivered the Sun in the Fulton Market district, and who later became a rich livery-stable keeper. Live lads like these, carrying out Day’s idea, wrought the greatest change in journalism that ever had been made, for they brought the paper to the people, something that could not be accomplished by the six-cent sheets with their lofty notions and comparatively high prices.

On the third day of the Sun’s life, with Wisner at the pen and Barney Flaherty “hollering” in the startled streets, the editor again expressed, this time more positively, his yearning that something would happen:

We newspaper people thrive best on the calamities of others. Give us one of your real Moscow fires, or your Waterloo battle-fields; let a Napoleon be dashing with his legions through the world, overturning the thrones of a thousand years and deluging the world with blood and tears; and then we of the types are in our glory.

The yearner had to wait thirty years for another Waterloo, but he got his “real Moscow fire” in about two years, and so close that it singed his eyebrows.

Lacking a Napoleon to exalt or denounce, Mr. Day used a bit of that same page for the publication of homelier news for the people:

The following are the drawn numbers of the New York consolidated lotteries of yesterday afternoon:

62 6 59 46 61 34 65 37 8 42

So Horace Greeley and his partner, with their tri-weekly paper, could not have been keeping all of the lottery patronage away from the Sun.

Over in the police column Mr. Wisner was supplying gems like the following:

A complaint was made by several persons who “thought it no sin to step to the notes of a sweet violin” and gathered under a window in Chatham Street, where a little girl was playing on a violin, when they were showered from a window above with the contents of a dye-pot or something of like nature. They were directed to ascertain their showerer.

The big story on the first page of the fourth issue of the Sun was a conversation between Envy and Candor in regard to the beauties of a Miss H., perhaps a fictitious person. But on the second page, at the head of the editorial column, was a real editorial article approving the course of the British government in freeing the slaves in the West Indies:

We supposed that the eyes of men were but half open to this case. We imagined that the slave would have to toil on for years and purchase what in justice was already his own. We did not once dream that light had so far progressed as to prepare the British nation for the colossal stride in justice and humanity and benevolence which they are about to make. The abolition of West Indian slavery will form a brilliant era in the annals of the world. It will circle with a halo of imperishable glory the brows of the transcendent spirits who wield the present destinies of the British Empire.

Would to Heaven that the honor of leading the way in this godlike enterprise had been reserved to our own country! But as the opportunity for this is passed, we trust we shall at least avoid the everlasting disgrace of long refusing to imitate so bright and glorious an example.

Thus the Sun came out for the freedom of the slave twenty-eight years before that freedom was to be accomplished in the United States through war. The Sun was the Sun of Day, but the hand was the hand of Wisner. That young man was an Abolitionist before the word was coined.

“Wisner was a pretty smart young fellow,” said Mr. Day nearly fifty years afterward, “but he and I never agreed. I was rather Democratic in my notions. Wisner, whenever he got a chance, was always sticking in his damned little Abolitionist articles.”

There is little doubt that Wisner wrote the article facing the Sun against slavery while he was waiting for something to turn up in the police-court. Then he went to the office, set up the article, as well as his piece about the arrest of Eliza Barry, of Bayard Street, for stealing a wash-tub, and put the type in the form. Considering that Wisner got four dollars a week for his break-o’-day work, he made a very good morning of that; and it is worthy of record that the next day’s Sun did not repudiate his assault on human servitude, although on September 10 Mr. Day printed an editorial grieving over the existence of slavery, but hitting at the methods of the Abolitionists.

These early issues were full of lively little “sunny” pieces, for instance:

Passing by the Beekman Street church early this morning, we discovered a milkman replenishing his lacteous cargo with Adam’s ale. We took the liberty to ask him, “Friend, why do ye do thus?” He replied, “None of your business”; and we passed on, determined to report him to the Grahamites.

A poem on Burns, by Halleck—perhaps reprinted from one of the author’s published volumes of verse—added literary tone to that morning’s Sun.

In the next issue was some verse by Willis, beginning:

Look not upon the wine when it

Is red within the cup!

Then, and for some years afterward, the Sun exhibited a special aversion to alcohol in text and head-lines. “Cursed Effects of Rum!” was one of its favourite head-lines.

The Sun was a week old before it contained dramatic criticism, its first subject in that field being the appearance of Mr. and Mrs. Wood at the Park Theatre in “Cinderella,” a comic opera. The paper’s first animal story was printed on September 12, recording the fact that on the previous Sunday about sixty wild pigeons stayed in a tree at the Battery nearly half an hour.

On September 14 the Sun printed its first illustration—a two-column cut of “Herschel’s Forty-Feet Telescope.” This was Sir W. Herschel, then dead some ten years, and the telescope was on his grounds at Slough, near Windsor, England. Another knighted Herschel with another telescope in a far land was to play a big part in the fortunes of the Sun, but that comes later. In the issue with the cut of the telescope was a paragraph about a rumour that Fanny Kemble, who had just captivated American theatregoers, had been married to Pierce Butler, of Philadelphia—as, indeed, she had.

Broadway seems to have had its lure as early as 1833, for in the Sun of September 17, on the first page, is a plaint by “Citizen”:

They talk of the pleasures of the country, but would to God I had never been persuaded to leave the labor of the city for such woful pleasures. Oh, Broadway, Broadway! In an evil hour did I forsake thee for verdant walks and flowery landscapes and that there tiresome piece of made water. What walk is so agreeable as a walk through the streets of New York? What landscape more flowery than those of the print-shops? And what water was made by man equal to the Hudson?

This was followed by uplifting little essays on “Suicide” and “Robespierre.” The chief news of the day—that John Quincy Adams had accepted a nomination from the Anti-Masons—was on an inside page. What was possibly of more interest to the readers, it was announced that thereafter a ton of coal would be two thousand pounds instead of twenty-two hundred and forty—Lackawanna, broken and sifted, six dollars and fifty cents a ton.

On Saturday, September 21, when it was only eighteen days old, the Sun adopted a new head-line. The letters remained the same, but the eagle device of the first issue was supplanted by the solar orb rising over hills and sea. This design was used only until December 2, when its place was taken by a third emblem—a printing-press shedding symbolical effulgence upon the earth.

The Sun’s first book-notice appeared on September 23, when it acknowledged the sixtieth volume of the “Family Library” (Harpers), this being a biography of Charlemagne by G. P. R. James. “It treats of a most important period in the history of France.” The Sun had little space then for book-reviews or politics. Of its attitude toward the great financial fight then being waged, this lone paragraph gives a good view:

The Globe of Monday contains in six columns the reasons which prompted the President to remove the public deposits from the United States Bank, which were read to his assembled cabinet on the 18th instant.

Nicholas Biddle and his friends could fill other papers with arguments, but the Sun kept its space for police items, stories of authenticated ghosts, and yarns about the late Emperor Napoleon. The removal of William J. Duane as Secretary of the Treasury got two lines on a page where a big shark caught off Barnstable got three lines, and the feeding of the anaconda at the American Museum a quarter of a column. Miss Susan Allen, who bought a cigar on Broadway and was arrested when she smoked it while she danced in the street, was featured more prominently than the expected visit to New York of Mr. Henry Clay, after whom millions of cigars were to be named. For the satisfaction of universal curiosity it must be reported that Miss Allen was discharged.

On October 1 of that same year—1833—the Sun came out for better fire-fighting apparatus, urging that the engines should be drawn by horses, as in London. In the same issue it assailed the gambling-house in Park Row, and scorned the allegation of Colonel Hamilton, a British traveller, that the tooth-brush was unknown in America. Slowly the paper was getting better, printing more local news; and it could afford to, for the penny Sun idea had taken hold of New York, and the sales were larger every week.

Wisner was stretching the police-court pieces out to nearly two columns. Now and then, perhaps when Mr. Day was away fishing, the reporter would slip in an Abolition paragraph or a gloomy poem on the horrors of slavery. But he was so valuable that, while his chief did not raise his salary of four dollars a week, he offered him half the paper, the same to be paid for out of the profits. And so, in January of 1834, Wisner became a half-owner of the Sun. Benton, another Sun printer, also wanted an interest, and left when he could not get it.

Before it was two months old the Sun had begun to take an interest in aeronautics. It printed a full column, October 16, 1833, on the subject of Durant’s balloon ascensions, and quoted Napoleon as saying that the only insurmountable difficulty of the balloon in war was the impossibility of guiding its course. “This difficulty Dr. Durant is now endeavoring to obviate.” And the Sun added:

May we not therefore look to the time, in perspective, when our atmosphere will be traversed with as much facility as our waters?

In the issue of October 17 a skit, possibly by Mr. Day himself, gave a picture of the trials of an editor of the period:

SCENE—An editor’s closet—editor solus.

“Well, a pretty day’s work of it I shall make. News, I have nothing—politics, stale, flat, and unprofitable—miscellany, enough of it—miscellany bills payable, and a miscellaneous list of subscribers with tastes as mi