CHAPTER III

THE FARMER OF THE MIDDLE WEST

That it may please Thee to give and preserve to our use the kindly fruits of the earth, so that in due time we may enjoy them.—The Litany.

WHEN spring marches up the Mississippi valley and the snows of the broad plains find companionship with the snows of yesteryear, the traveller, journeying east or west, is aware that life has awakened in the fields. The winter wheat lies green upon countless acres; thousands of ploughshares turn the fertile earth; the farmer, after the enforced idleness of winter, is again a man of action.

Last year (1917), that witnessed our entrance into the greatest of wars, the American farmer produced 3,159,000,000 bushels of corn, 660,000,000 bushels of wheat, 1,587,000,000 bushels of oats, 60,000,000 bushels of rye. From the day of our entrance into the world struggle against autocracy the American farm has been the subject of a new scrutiny. In all the chancelleries of the world crop reports and estimates are eagerly scanned and tabulated, for while the war lasts and far into the period of rehabilitation and reconstruction that will follow, America must bear the enormous responsibility, not merely of training and equipping armies, building ships, and manufacturing munitions, but of feeding the nations. The farmer himself is roused to a new consciousness of his importance; he is aware that thousands of hands are thrust toward him from over the sea, that every acre of his soil and every ear of corn and bushel of wheat in his bins or in process of cultivation has become a factor in the gigantic struggle to preserve and widen the dominion of democracy.

I

“Better be a farmer, son; the corn grows while you sleep!”

This remark, addressed to me in about my sixth year by my great-uncle, a farmer in central Indiana, lingered long in my memory. There was no disputing his philosophy; corn, intelligently planted and tended, undoubtedly grows at night as well as by day. But the choice of seed demands judgment, and the preparation of the soil and the subsequent care of the growing corn exact hard labor. My earliest impressions of farm life cannot be dissociated from the long, laborious days, the monotonous plodding behind the plough, the incidental “chores,” the constant apprehensions as to drought or flood. The country cousins I visited in Indiana and Illinois were all too busy to have much time for play. I used to sit on the fence or tramp beside the boys as they drove the plough, or watch the girls milk the cows or ply the churn, oppressed by an overmastering homesickness. And when the night shut down and the insect chorus floated into the quiet house the isolation was intensified.

My father and his forebears were born and bred to the soil; they scratched the earth all the way from North Carolina into Kentucky and on into Indiana and Illinois. I had just returned, last fall, from a visit to the grave of my grandfather in a country churchyard in central Illinois, round which the corn stood in solemn phalanx, when I received a note from my fifteen-year-old boy, in whom I had hopefully looked for atavistic tendencies. From his school in Connecticut he penned these depressing tidings:

“I have decided never to be a farmer. Yesterday the school was marched three miles to a farm where the boys picked beans all afternoon and then walked back. Much as I like beans and want to help Mr. Hoover conserve our resources, this was rubbing it in. I never want to see a bean again.”

I have heard a score of successful business and professional men say that they intended to “make farmers” of their boys, and a number of these acquaintances have succeeded in sending their sons through agricultural schools, but the great-grandchildren of the Middle Western pioneers are not easily persuaded that farming is an honorable calling.

It isn’t necessary for gentlemen who watch the tape for crop forecasts to be able to differentiate wheat from oats to appreciate the importance to the prosperous course of general business of a big yield in the grain-fields; but to the average urban citizen farming is something remote and uninteresting, carried on by men he never meets in regions that he only observes hastily from a speeding automobile or the window of a limited train. Great numbers of Middle Western city men indulge in farming as a pastime—and in a majority of cases it is, from the testimony of these absentee proprietors, a pleasant recreation but an expensive one. However, all city men who gratify a weakness for farming are not faddists; many such land-owners manage their plantations with intelligence and make them earn dividends. Mr. George Ade’s Indiana farm, Hazelden, is one of the State’s show-places. The playwright and humorist says that its best feature is a good nine-hole golf-course and a swimming-pool, but from his “home plant” of 400 acres he cultivates 2,000 acres of fertile Hoosier soil.

A few years ago a manufacturer of my acquaintance, whose family presents a clear urban line for a hundred years, purchased a farm on the edge of a river—more, I imagine, for the view it afforded of a pleasant valley than because of its fertility. An architect entered sympathetically into the business of making habitable a century-old log house, a transition effected without disturbing any of the timbers or the irregular lines of floors and ceilings. So much time was spent in these restorations and readjustments that the busy owner in despair fell upon a mail-order catalogue to complete his preparations for occupancy. A barn, tenant’s house, poultry-house, pump and windmill, fencing, and every vehicle and tool needed on the place, including a barometer and wind-gauge, he ordered by post. His joy in his acres was second only to his satisfaction in the ease with which he invoked all the apparatus necessary to his comfort. Every item arrived exactly as the catalogue promised; with the hired man’s assistance he fitted the houses together and built a tower for the windmill out of concrete made in a machine provided by the same establishment. His only complaint was that the catalogue didn’t offer memorial tablets, as he thought it incumbent upon him to publish in brass the merits of the obscure pioneer who had laboriously fashioned his cabin before the convenient method of post-card ordering had been discovered.

II

Imaginative literature has done little to invest the farm with glamour. The sailor and the warrior, the fisherman and the hunter are celebrated in song and story, but the farmer has inspired no ringing saga or iliad, and the lyric muse has only added to the general joyless impression of the husbandman’s life. Hesiod and Virgil wrote with knowledge of farming; Virgil’s instructions to the ploughman only need to be hitched to a tractor to bring them up to date, and he was an authority on weather signs. But Horace was no farmer; the Sabine farm is a joke. The best Gray could do for the farmer was to send him homeward plodding his weary way. Burns, at the plough, apostrophized the daisy, but only by indirection did he celebrate the joys of farm life. Wordsworth’s “Solitary Reaper” sang a melancholy strain; “Snow-Bound” offers a genial picture, but it is of winter-clad fields. Carleton’s “Farm Ballads” sing of poverty and domestic infelicity. Riley made a philosopher and optimist of his Indiana farmer, but his characters are to be taken as individuals rather than as types. There is, I suppose, in every Middle Western county a quizzical, quaint countryman whose sayings are quoted among his neighbors, but the man with a hundred acres of land to till, wood to cut, and stock to feed is not greatly given to poetry or humor.

English novels of rural life are numerous but they are usually in a low key. I have a lingering memory of Hardy’s “Woodlanders” as a book of charm, and his tragic “Tess” is probably fiction’s highest venture in this field. “Lorna Doone” I remember chiefly because it established in me a distaste for mutton. George Eliot and George Meredith are other English novelists who have written of farm life, nor may I forget Mr. Eden Phillpotts. French fiction, of course, offers brilliant exceptions to the generalization that literature has neglected the farmer; but, in spite of the vast importance of the farm in American life, there is in our fiction no farm novel of distinction. Mr. Hamlin Garland, in “Main Traveled Roads” and in his autobiographical chronicle “A Son of the Middle Border,” has thrust his plough deep; but the truth as we know it to be disclosed in these instances is not heartening. The cowboy is the jolliest figure in our fiction, the farmer the dreariest. The shepherd and the herdsman have fared better in all literatures than the farmer, perhaps because their vocations are more leisurely and offer opportunities for contemplation denied the tiller of the soil. The Hebrew prophets and poets were mindful of the pictorial and illustrative values of herd and flock. It is written, “Our cattle also shall go with us,” and, journeying across the mountain States, where there is always a herd blurring the range, one thinks inevitably of man’s long migration in quest of the Promised Land.

The French peasant has his place in art, but here again we are confronted by joylessness, though I confess that I am resting my case chiefly upon Millet. What Remington did for the American cattle-range no one has done for the farm. Fields of corn and wheat are painted truthfully and effectively, but the critics have withheld their highest praise from these performances. Perhaps a corn-field is not a proper subject for the painter; or it may be that the Maine rocks or a group of birches against a Vermont hillside “compose” better or are supported by a nobler tradition. The most alluring pictures I recall of farm life have been advertisements depicting vast fields of wheat through which the delighted husbandman drives a reaper with all the jauntiness of a king practising for a chariot-race.

I have thus run skippingly through the catalogues of bucolic literature and art to confirm my impression as a layman that farming is not an affair of romance, poetry, or pictures, but a business, exacting and difficult, that may be followed with success only by industrious and enlightened practitioners. The first settlers of the Mississippi valley stand out rather more attractively than their successors of what I shall call the intermediate period. There was no turning back for the pioneers who struck boldly into the unknown, knowing that if they failed to establish themselves and solve the problem of subsisting from the virgin earth they would perish. The battle was to the strong, the intelligent, the resourceful. The first years on a new farm in wilderness or prairie were a prolonged contest between man and nature, nature being as much a foe as an ally. That the social spark survived amid arduous labor and daily self-sacrifice is remarkable; that the earth was subdued to man’s will and made to yield him its kindly fruits is a tribute to the splendid courage and indomitable faith of the settlers.

These Middle Western pioneers were in the fullest sense the sons of democracy. The Southern planter with the traditions of the English country gentleman behind him and, in slavery time, representing a survival of the feudal order, had no counterpart in the West, where the settler was limited in his holdings to the number of acres that he and his sons could cultivate by their own labor. I explored, last year, much of the Valley of Democracy, both in seed-time and in harvest. We had been drawn at last into the world war, and its demands and conjectures as to its outcome were upon the lips of men everywhere. It was impossible to avoid reflecting upon the part these plains have played in the history of America and the increasing part they are destined to play in the world history of the future. Every wheat shoot, every stalk of corn was a new testimony to the glory of America. Not an acre of land but had been won by intrepid pioneers who severed all ties but those that bound them to an ideal, whose only tangible expression was the log court-house where they recorded the deeds for their land or the military post that afforded them protection. At Decatur, Illinois, one of these first court-houses still stands, and we are told that within its walls Lincoln often pleaded causes. American democracy could have no finer monument than this; the imagination quickens at the thought of similar huts reared by the axes of the pioneers to establish safeguards of law and order on new soil almost before they had fashioned their habitations. It seemed to me that if the Kaiser had known the spirit in which these august fields were tamed and peopled, or the aspirations, the aims and hopes that are represented in every farmhouse and ranch-house between the Alleghanies and the Rockies, he would not so contemptuously have courted our participation against him in his war for world domination.

What I am calling, for convenience, the intermediate period in the history of the Mississippi valley, began when the rough pioneering was over, and the sons of the first settlers came into an inheritance of cleared land. In the Ohio valley the Civil War found the farmer at ease; to the west and northwest we must set the date further along. The conditions of this intermediate period may not be overlooked in any scrutiny of the farmer of these changed and changing times. When the cloud of the Civil War lifted and the West began asserting itself in the industrial world, the farmer, viewing the smoke-stacks that advertised the entrance of the nearest towns and cities into manufacturing, became a man with a grievance, who bitterly reflected that when rumors of “good times” reached him he saw no perceptible change in his own fortunes or prospects, and in “bad times” he felt himself the victim of hardship and injustice. The glory of pioneering had passed with his father and grandfather; they had departed, leaving him without their incentive of urgent necessity or the exultance of conquest. There may have been some weakening of the fibre, or perhaps it was only a lessening of the tension now that the Indians had been dispersed and the fear of wild beasts lifted from his household.

There were always, of course, men who were pointed to as prosperous, who for one reason or another “got ahead” when others fell behind. They not only held their acres free of mortgage but added to their holdings. These men were very often spoken of as “close,” or tight-fisted; in Mr. Brand Whitlock’s phrase they were “not rich, but they had money.” And, having money and credit, they were sharply differentiated from their neighbors who were forever borrowing to cover a shortage. These men loomed prominently in their counties; they took pride in augmenting the farms inherited from pioneer fathers; they might sit in the State legislature or even in the national Congress. But for many years the farmer was firmly established in the mind of the rest of the world as an object of commiseration. He occupied an anomalous position in the industrial economy. He was a landowner without enjoying the dignity of a capitalist; he performed the most arduous tasks without recognition by organized labor. He was shabby, dull, and uninteresting. He drove to town over a bad road with a load of corn, and, after selling or bartering it, negotiated for the renewal of his mortgage and stood on the street corner, an unheroic figure, until it was time to drive home. He symbolized hard work, hard luck, and discouragement. The saloon, the livery-stable, and the grocery where he did his trading were his only loafing-places. The hotel was inhospitable; he spent no money there and the proprietor didn’t want “rubes” or “jays” hanging about. The farmer and his wife ate their midday meal in the farm-wagon or at a restaurant on the “square” where the frugal patronage of farm folk was not despised.

The type I am describing was often wasteful and improvident. The fact that a degree of mechanical skill was required for the care of farm-machinery added to his perplexities; and this apparatus he very likely left out-of-doors all winter for lack of initiative to build a shed to house it. I used to pass frequently a farm where a series of reapers in various stages of decrepitude decorated the barn-lot, with always a new one to heighten the contrast.

The social life of the farmer centred chiefly in the church, where on the Sabbath day he met his neighbors and compared notes with them on the state of the crops. Sundays on the farm I recall as days of gloom that brought an intensification of week-day homesickness. The road was dusty; the church was hot; the hymns were dolorously sung to the accompaniment of a wheezy organ; the sermon was long, strongly flavored with brimstone, and did nothing to lighten

“the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world.”

The horses outside stamped noisily in their efforts to shake off the flies. A venturous bee might invade the sanctuary and arouse hope in impious youngsters of an attack upon the parson—a hope never realized! The preacher’s appetite alone was a matter for humor; I once reported a Methodist conference at which the succulence of the yellow-legged chickens in a number of communities that contended for the next convocation was debated for an hour. The height of the country boy’s ambition was to break a colt and own a side-bar buggy in which to take a neighbor’s daughter for a drive on Sunday afternoon.

Community gatherings were rare; men lived and died in the counties where they were born, “having seen nothing, still unblest.” County and State fairs offered annual diversion, and the more ambitious farmers displayed their hogs and cattle, or mammoth ears of corn, and reverently placed their prize ribbons in the family Bibles on the centre-tables of their sombre parlors. Cheap side-shows and monstrosities, horse-races and balloon ascensions were provided for their delectation, as marking the ultimate height of their intellectual interests. A characteristic “Riley story” was of a farmer with a boil on the back of his neck, who spent a day at the State fair waiting for the balloon ascension. He inquired repeatedly: “Has the balloon gone up yit?” Of course when the ascension took place he couldn’t lift his head to see the balloon, but, satisfied that it really had “gone up,” he contentedly left for home. (It may be noted here that the new status of the farmer is marked by an improvement in the character of amusements offered by State-fair managers. Most of the Western States have added creditable exhibitions of paintings to their attractions, and in Minnesota these were last year the subject of lectures that proved to be very popular.)

The farmer, in the years before he found that he must become a scientist and a business man to achieve success, was the prey of a great variety of sharpers. Tumble-down barns bristled with lightning-rods that cost more than the structures were worth. A man who had sold cooking-ranges to farmers once told me of the delights of that occupation. A carload of ranges would be shipped to a county-seat and transferred to wagons. It was the agent’s game to arrive at the home of a good “prospect” shortly before noon, take down the old, ramshackle cook-stove, set up the new and glittering range, and assist the womenfolk to prepare a meal. The farmer, coming in from the fields and finding his wife enchanted, would order a range and sign notes for payment. These obligations, after the county had been thoroughly exploited, would be discounted at the local bank. In this way the farmer’s wife got a convenient range she would never have thought of buying in town, and her husband paid an exorbitant price for it.

The farmer’s wife was, in this period to which I am referring, a poor drudge who appeared at the back door of her town customers on Saturday mornings with eggs and butter. She was copartner with her husband, but, even though she might have “brought” him additional acres at marriage, her spending-money was limited to the income from butter, eggs, and poultry, and even this was dependent upon the generosity of the head of the house. Her kitchen was furnished with only the crudest housewifery apparatus; labor-saving devices reached her slowly. In busy seasons, when there were farm-hands to cook for, she might borrow a neighbor’s daughter to help her. Her only relief came when her own daughters grew old enough to assist in her labors. She was often broken down, a prey to disease, before she reached middle life. Her loneliness, the dreary monotony of her existence, the prevailing hopelessness of never “catching up” with her sewing and mending, often drove her insane. The farmhouse itself was a desolate place. There is a mustiness I associate with farmhouses—the damp stuffiness of places never reached by the sun. With all the fresh air in the world to draw from, thousands of farmhouses were ill-lighted and ill-ventilated, and farm sanitation was of the most primitive order.

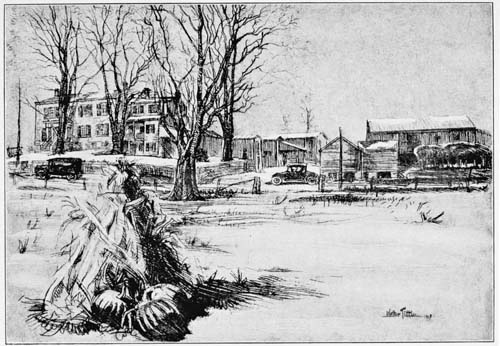

A typical old homestead of the Middle West.

The farm on which Tecumseh was born.

I have dwelt upon the intermediate period merely to heighten the contrast with the new era—an era that finds the problem of farm regeneration put squarely up to the farmer.

III

The new era really began with the passage of the Morrill Act, approved July 2, 1862, though it is only within a decade that the effects of this law upon the efficiency and the character of the farmer have been markedly evident. The Morrill Act not only made the first provision for wide-spread education in agriculture but lighted the way for subsequent legislation that resulted in the elevation of the Department of Agriculture to a cabinet bureau, the system of agriculture experiment-stations, the co-operation of federal and State bureaus for the diffusion of scientific knowledge pertaining to farming and the breeding and care of live-stock, and the recent introduction of vocational training into country schools.

It was fitting that Abraham Lincoln, who had known the hardest farm labor, should have signed a measure of so great importance, that opened new possibilities to the American farmer. The agricultural colleges established under his Act are impressive monuments to Senator Morrill’s far-sightedness. When the first land-grant colleges were opened there was little upon which to build courses of instruction. Farming was not recognized as a science but was a form of hard labor based on tradition and varied only by reckless experiments that usually resulted in failure. The first students of the agricultural schools, drawn largely from the farm, were discouraged by the elementary character of the courses. Instruction in ploughing, to young men who had learned to turn a straight furrow as soon as they could tiptoe up to the plough-handles, was not calculated to inspire respect for “book farming” either in students or their doubting parents.

The farmer and his household have found themselves in recent years the object of embarrassing attentions not only from Washington, the land-grant colleges, and the experiment-stations, but countless private agencies have “discovered” the farmer and addressed themselves determinedly to the amelioration of his hardships. The social surveyor, having analyzed the city slum to his satisfaction, springs from his automobile at the farmhouse door and asks questions of the bewildered occupants that rouse the direst apprehensions. Sanitarians invade the premises and recommend the most startling changes and improvements. Once it was possible for typhoid or diphtheria to ravage a household without any interference from the outside world; now a health officer is speedily on the premises to investigate the old oaken bucket, the iron-bound bucket, that hangs in the well, and he very likely ties and seals the well-sweep and bids the farmer bore a new well, in a spot kindly chosen for him, where the barn-lot will not pollute his drinking-water. The questionnaire, dear to the academic investigator, is constantly in circulation. Women’s clubs and federations thereof ponder the plight of the farmer’s wife and are eager to hitch her wagon to a star. Home-mission societies, alarmed by reports of the decay of the country church, have instituted surveys to determine the truth of this matter. The consolidation of schools, the introduction of comfortable omnibuses to carry children to and from home, the multiplication of country high schools, with a radical revision of the curriculum, the building of two-story schoolhouses in place of the old one-room affair in which all branches were taught at once, and the use of the schoolhouse as a community centre—these changes have dealt a blow to the long-established ideal of the red-mittened country child, wading breast-high through snow to acquaint himself with the three R’s and, thus fortified, enter into the full enjoyment of American democracy. Just how Jefferson would look upon these changes and this benignant paternalism I do not know, nor does it matter now that American farm products are reckoned in billions and we are told that the amount must be increased or the world will starve.

The farmer’s mail, once restricted to an occasional letter, began to be augmented by other remembrances from Washington than the hollyhock-seed his congressman occasionally conferred upon the farmer’s wife. Pamphlets in great numbers poured in upon him, filled with warnings and friendly counsel. The soil he had sown and reaped for years, in the full confidence that he knew all its weaknesses and possibilities, he found to be something very different and called by strange names. His lifelong submission to destructive worms and hoppers was, he learned, unnecessary if not criminal; there were ways of eliminating these enemies, and he shyly discussed the subject with his neighbors.

In speaking of the farmer’s shyness I have stumbled into the field of psychology, whose pitfalls are many. The psychologists have as yet played their search-light upon the farm guardedly or from the sociologist’s camp. I here condense a few impressions merely that the trained specialist may hasten to convict me of error. The farmer of the Middle West—the typical farmer with approximately a quarter-section of land—is notably sensitive, timid, only mildly curious, cautious, and enormously suspicious. (“The farmer,” a Kansas friend whispers, “doesn’t vote his opinions; he votes his suspicions!”) In spite of the stuffing of his rural-route box with instructive literature designed to increase the productiveness of his acres and lighten his own toil, he met the first overtures of the “book-l’arnin’” specialist warily, and often with open hostility. The reluctant earth has communicated to the farmer, perhaps in all times and in all lands, something of its own stubbornness. He does not like to be driven; he is restive under criticism. The county agent of the extension bureau who seeks him out with the best intentions in the world, to counsel him in his perplexities, must approach him diplomatically. I find in the report of a State director of agricultural extension a discreet statement that “the forces of this department are organized, not for purposes of dictation in agricultural matters but for service and assistance in working out problems pertaining to the farm and the community.” The farmer, unaffected as he is by crowd psychology, is not easily disturbed by the great movements and tremendous crises that rouse the urban citizen. He reads his newspaper perhaps more thoroughly than the city man, at least in the winter season when the distractions of the city are greatest and farm duties are the least exacting. Surrounded by the peace of the fields, he is not swayed by mighty events, as men are who scan the day’s news on trains and trolleys and catch the hurried comments of their fellow citizens as they plunge through jostling throngs. Professor C. J. Galpin, of Wisconsin University, aptly observes that, while the farmer trades in a village, he shares the invisible government of a township, which “scatters and mystifies” his community sense.

It was a matter of serious complaint that farmers responded very slowly in the first Liberty Loan campaigns. At the second call vigorous attempts were made through the corn belt to rouse the farmer, who had profited so enormously by the war’s augmentation of prices. In many cases country banks took the minimum allotment of their communities and then sent for the farmers to come in and subscribe. The Third Loan, however, was met in a much better spirit. The farmer is unused to the methods by which money-raising “drives” are conducted and he resents being told that he must do this, that, or the other thing. Townfolk are beset constantly by demands for money for innumerable causes; there is always a church, a hospital, a social-service house, a Y. M. C. A. building, or some home or refuge for which a special appeal is being made. There is a distinct psychology of generosity based largely on the inspiration of thoroughly organized effort, where teams set forth with a definite quota to “raise” before a fixed hour, but the farmer was long immune from these influences.

In marked contrast with the small farmer, who wrests a scant livelihood from the soil, is his neighbor who boasts a section or a thousand acres, who is able to utilize the newest machinery and to avail himself of the latest disclosures of the laboratories, to increase his profits. One visits these large farms with admiration for the fruitful land, the perfect equipment, the efficient method, and the alert, wide-awake owner. He lives in a comfortable house, often electric-lighted and “plumbed,” visits the cities, attends farm conferences, and is keenly alive to the trend of public affairs. If the frost nips his corn he is aware of every means by which “soft” corn may be handled to the best advantage. He knows how many cattle and hogs his own acres will feed, and is ready with cash to buy his neighbors’ corn and feed it to stock he buys at just the right turn of the market. It is possible for a man to support himself and a family on eighty acres; I have talked with men who have done this; but they “just about get by.” The owner of a big farm, whose modern house and rich demesne are admired by the traveller, is a valued customer of a town or city banker; the important men of his State cultivate his acquaintance, with resulting benefits in a broader outlook than his less-favored neighbors enjoy. Farmers of this class are themselves usually money-lenders or shareholders in country banks, and they watch the trend of affairs from the view-point of the urban business man. They live closer to the world’s currents and are more accessible and responsive to appeals of every sort than their less-favored brethren.

But it is the small farmer, the man with the quarter-section or less, who is the special focus of the search-light of educator, scientist, and sociologist. During what I have called the intermediate period—the winter of the farmer’s discontent—the politicians did not wholly ignore him. The demagogue went forth in every campaign