The Highest Thing?

Chaucer’s romances really are unlike the run of the genre. “Perhaps it is true to say that in English, at least, only the Gawain-poet and Chaucer followed Chrétien [de Troyes] in the development of a self-conscious hero who realizes in himself the question at issue.”209 Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale has been proposed as something new, perhaps a “philosophical romance.” And yet, if he created a new genre, why would he be satisfied with creating just one instance of the type? The fact that the Knight’s Tale is the most obvious example doesn’t mean that Chaucer isn’t trying to make the same point elsewhere. Far more likely that he is trying to bring it home in his other writings. “It is... the great achievement of Chaucer, as I see it, in his Wife of Bath’s Tale and Franklin’s Tale to have extended the courtly concepts involved in the definition of a ‘gentil’ man until their class-basis, their narrowly conceived aristocratic tenor, becomes irrelevant.”210

To be sure, trouthe is not always rigidly followed — in one sense, the end of the Franklin’s Tale sees none of the characters actually fulfill their promises, leading A. C. Spearing to argue that “True freedom is gained by going beyond trouthe.”211 But this is the narrow view. Trouthe puts the characters in a bind, and Spearing calls the solution by another Chaucerian word, gentil(l)esse, for which the closest thing to a modern equivalent is probably “nobility.”212 But gentilesse can only operate where trouthe is in force. Trouthe comes first.

The fact that Chaucer is trying to write so universally makes it noteworthy that we have found trouthe every time we have sought it in his romances. And, each time, it has been triumphant.

It should be conceded that this is not always so in the non-romances. The Pardoner’s Tale is an obvious example: The three roisterers are “sworn brothers” who set out on a noble (if absurd) quest to slay Death. Then they find the gold — and the promises to each other, and the quest, all go out the window.213 Their trouthe utterly fails.

And yet, the very fact that they all end up dead shows, again, that trouthe holds. Things go wrong the moment the drunkards abandon their proper relationship with each other. Each one pays with his life.

The tragedy of Troilus and Criseyde is one of trouthe: “gentle and lovely as she was, Criseyde could not stand fast in ‘trouthe.’”214 Troilus, whose trouthe was stronger, paid with pain. And who of us does not know that story? Still, we should keep in mind that one of the motivating factors is that Troilus thought he had a pledge....

It is often stressed that Chaucer derived much of his philosophy from Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, which certainly supplied many of his ideas: “Chaucer was immensely influenced by it. He translated the whole of it into prose, and constantly made use of its ideas. The doctrine of gentilesse, the nature of chance, the problem of free will are all dealt with by Boethius and helped to form Chaucer’s thought on these matters, and to guide him in some of the deepest passages of the Knight’s Tale and Troilus and Criseyde.”215 But simply because Chaucer found many of his ideas in Boethius does not imply that they all appealed to him in the same way. Chaucer clearly had intellectual ideas on the subject of free will, for instance, but he seems to have had an emotional attachment to trouthe.

Romances often have supernatural elements — King Arthur and his knights fight dragons; Orfeo goes to Faërie in Sir Orfeo; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight involves a miraculous survival of the Beheading Game. Chaucer certainly uses some of these elements — but downplays them. The Knight’s Tale involves the intervention of the Gods — but only to bring about things that could have happened anyway. The Wife of Bath’s Tale involves a magical transformation, but none of the outside magic that transformed the Loathly Lady in the parallel tales — the Wife even laments that there is no longer any access to magic beings:

Wommen may go saufly up and doun.

In every bussh or under every tree

There is noon oother incubus but he,216

meaning that women have to settle for friars, rather than incubi, if they want an illicit liaison. In The Franklin’s Tale, the Clerk makes the rocks of Brittany seem to disappear, but it is only a seeming; they will be back. There are marvels in Chaucer, but no gratuitous marvels. The magic we see is almost rational; although Chaucer doesn’t know what rules it operates under, he seems to believe there are rules: magic “was envisioned as a science employing not spirits but specialized knowledge of natural phenomena.”217 Wonders can have a tendency to take over a romance — as, indeed, they threatened to do with the Squire’s Tale (could that be why Chaucer dropped it?). So can sequences of adventure after adventure. Chaucer wants none of that; he wants us to concentrate on the characters’ virtues.218

In an earlier era, Chaucer might have used his tales to make his case for the Church and its doctrine, as (e.g.) Dante had done — Chaucer, after all, seems to have admired Dante. But Chaucer wrote in the era of the Great Schism, when there were two rival Popes,219 as well as in the period when John Wycliffe was writing; it was a time when the Church was unusually hard to support. Chaucer gives every sign of being a proper Catholic — after all, his pilgrims are on their way to the shrine of Thomas Becket, even if they don’t seem to spend their time as proper pilgrims should220 — but his treatment of Church issues is confined to generalities.221 Chaucer’s own pilgrimage is directed toward another end.

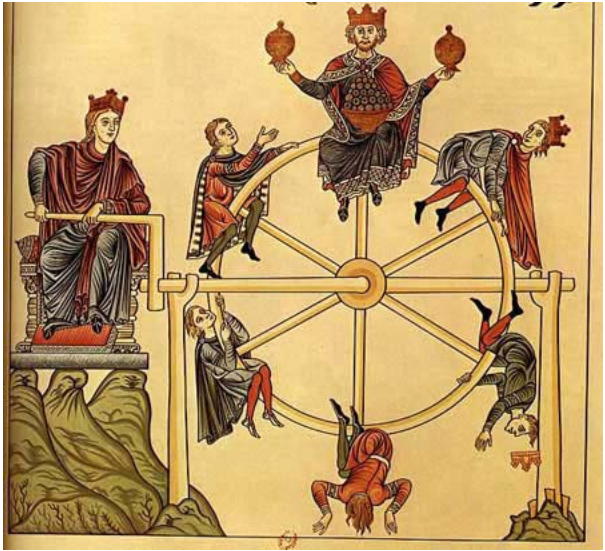

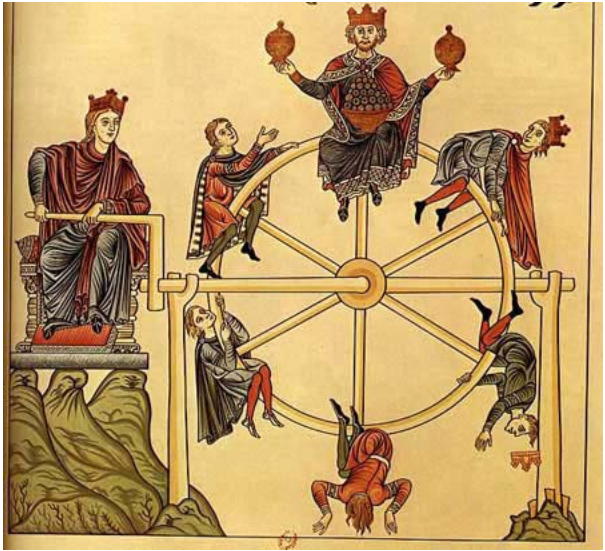

Manuscript illustration of the “Wheel of Fortune”: The goddess Fortune turns the wheel which raises some up and causes others to fall to their doom. From the copy of Harrad of Landsberg’s Hortus Deliciarum (Garden of Delights) in the Paris National Library.

It is famous that people in the Middle Ages believed in the inconstancy of fortune — in the Wheel of Fortune that lifted some and threw off others. Indeed, this was one of the key concepts of the philosophy of Boethius which Chaucer revered so deeply;222 Chaucer refers to the Wheel of Fortune in The Knight’s Tale and Troilus and Criseyde and elsewhere.223 But this is all the more reason for Chaucer to have embraced trouthe: it is something that cannot be taken away or limited by fortune. If you keep trouthe, you always have that to cling to.

Chaucer goes so far as to regard those who violate trouthe as traitors — e.g. when Aeneas betrays Dido, “he to hir a traytour was.”224 Treason, in the Middle Ages, was the most severe sentence imposed by the royal courts; the punishment was generally death by torture.

Of course, aspects of trouthe exist in other authors’ writings. The whole plot of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is about a pledged word kept, and then slightly violated, as Gawain first heads for the Green Chapel to face the fatal reverse stroke and then fails to exchange all his winnings with his host. Sir Orfeo is the tale of a man who never gives up his pledge to his wife. The lay of Havelok the Dane, and Malory’s tale of Balin, show that “Worthiness… and good deeds are not in arrayment, but manhood and worship is hid within a man’s person.”225 But the combination of these is found more fully in Chaucer than even in the Green Knight.

It might well be that Chaucer only slowly came to view trouthe as so important. In the Book of the Duchess we see trouthe, but it is rather limited in scope, restricted to the marriage of the Black Knight and Blanche. Although, even there, Chaucer gives the word a genuine richness — consider what happens when the Black Knight finally declares that “White” is dead:

“‘I have lost more than thow wenest.’

Got wot, allas! Ryght that was she!”

“Allas, sir, how? What may that be?”

“She ys ded!” “Nay!” “Yis, be my trouthe!”226

Note that the Knight swears that it is true that the Duchess to whom he was betrothed is dead. Of course “By my truth” is a perfectly reasonable and standard oath — but here it means much more.

The situation in Troilus and Criseyde is much fuller and yet more ambiguous. “As we move toward the conclusion of the work, trouthe has become both truly admirable — almost what Arveragus calls it in the Franklin’s Tale, ‘the hyeste thyng that man may kepe’ (1479) — and also something we covertly dislike and are ashamed of ourselves for disliking.”227 This comment of Lambert’s suggests a certain practical experience with rejection of trouthe — and one which strikes me as very real; I know that people don’t like my trouthe! This might explain why, even though Troilus is the noblest and truest of the characters in Troilus and Criseyde, “Criseyde, the heroine, and Pandarus, the friend and go-between, are… the two most comprehensible [characters] to the reader of today.”228

“The sens of romance is... ‘the claim of the ideal.”229 That is, a romance is supposed to reveal how things are supposed to work. And it appears that what Chaucer is trying to reveal is trouthe.

It is very hard for people to understand emotions that they don’t share. It is often possible to understand the reasoning of people we don’t agree with — I can understand both ends of the American political spectrum, even though I clearly stand at one end of it. But emotions are different. Think about how young children react to adult romantic feelings — “mushy stuff.” As an autistic, I never understood why people cared about “human interest stories”; I still don’t, but at least now I know that people are different and that to like them is normal.

So how would people respond to an emotion they don’t have? They find it incomprehensible — as most of us find Griselda incomprehensible. Perhaps Chaucer was right: trouthe needs demonstration.