It’s Only Fiction, Right?

The above arguments are, I think, enough reason to believe that people in the Middle Ages would have accepted the reality of trouthe. They would have believed in Dorigen’s dilemma; they would have wanted to accept Griselda. But that still leaves a stumbling block. Is Griselda, in particular, even possible? The fact that the medieval mind admired her emotions does not make her real, or even realistic. Even fictional characters must be life-like. The Clerk himself (following Petrarch, Chaucer’s source) said that, for most women, what Griselda did was impossible:

This storie is seyd nat for that wyves sholde

Folwen Grisilde as in humylitee,

For it were inportable, though they wolde....230

So why tell the tale? Could there be someone who actually showed Griselda’s virtues, who would do what she did?

I think there could have been. Some whose loyalty was fixed, determined, un-renounceable. Someone, perhaps… autistic?

Chaucer no more expects everyone to display perfect trouthe than Petrarch expected every woman to be Griselda. But perhaps — one may hope — some can.

In terms of personality, Griselda is very reminiscent of an autistic person, who will give absolute, total, passionate, extreme loyalty. Everything in the horrid Clerk’s Tale makes sense if we assume Griselda is an autistic. I have done this myself: made a promise of total devotion — and not even to a spouse, merely to a friend — and maintained it in the face of complete rejection. This is my trouthe. It is who I am.

Could Chaucer have known a Griselda? That is, someone with this autistic constancy? Could it even have been Chaucer himself?231

There are other hints of sympathy with an autistic viewpoint in Chaucer. In The Book of the Duchess we read of the Black Knight’s initial rejection: “He... re-created the woe of her first ‘Nay’ (1243), which he experienced as a kind of death: ‘I nam but ded’ (1188, cf. 204). The joy that followed her acceptance... is by contrast a return to life.”232 I, an autistic, have known this feeling — in one extreme case, when a friend simply told me to ride a different bus home from work, it caused me to become severely depressed.

Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer’s most important work other than the Canterbury Tales, features an interesting twist: “Unexpectedly, [Troilus’s] reaction to the loss of Criseyde is not to call down upon her the thunderbolts of the gods, as did Boccaccio’s Troilo, but to acknowledge that the unwaveringness of his love for Criseyde is indeed the very ground of his being:233

“Thorugh which I se that clene out of youre mynde

Ye han me cast — and I ne kan ne may....”234

This again is familiar: autistics tend to be extremely loyal, to friends as well as lovers, and they almost never release those feelings or, in my experience, turn vengeful. They just suffer. Of course, many other lovers suffer also, but the fact that Chaucer here changed Boccaccio would seem to be an indication that this is how he understands love.

Chaucer’s use of character is interesting. One of the most beloved parts of the Canterbury Tales is the sketches of the travelers at the beginning — but these are descriptions, not psychological studies. Coleridge accused Chaucer of not showing the “interior nature of humanity.”235 Wayne Schumaker wrote that “nowhere in the Canterbury Tales does Chaucer commit himself utterly to the implications of personality.”236 In The Merchant’s Tale “The events and characters are so close to type that they have little individuality.”237 We repeatedly see characters who are merely sketched out, as Palamon and Arcite were, or made almost a caricature of a particular trait, as Griselda is a caricature of obedience. Even Troilus and Criseyde, which is a deep study in personalities, has been seen as lacking in psychological depth: “as in the Canterbury Tales, Chaucer is here essentially the comic poet. He avoids the deeper aspects of the situation....”238 “For him the surface of life provided so much of interest that he seldom attempted to plumb its depths. To some extent it seems that he did not consider the deeper aspects of human existence as fit matters for poetry.”239 Or is it that he didn’t understand how others felt about them? This is just the sort of thing we would expect of an autistic with a rather superficial understanding of others’ emotions.

An astounding feature of Troilus and Criseyde is an extension it makes on the idea of dying for love. In the poem, we see the possibility dying for “mere” friendship treated with great seriousness.240 In a world where Shakespeare can say that men do not die for love, this probably sounds absurd — but as an autistic, I can only say that this sounds perfectly reasonable and, indeed, close to my own experience. The line between friendship and love, in Troilus, is very faint, almost unnoticeable241 — again, close to my own experience. I gather that most people feel a great difference between friendship and love. For me, the great gap is between casual and close friendships, not between close friendship and love.

There are multiple hints of suicide in Chaucer. Pandarus threatens it before Criseyde, Troilus works at it, Dorigen contemplates it. It is mentioned especially often in the Legend of Good Women; many of the women, plus Antony and Pyramus, end their own lives.242 In a Catholic world that held suicide a grave sin, this is very surprising — but less surprising for an autistic, since suicidal ideation is common for them and a significant fraction of them die by suicide.

The fourteenth century — an era that began with famines and storms, and continued with war and the Black Death — was an era of fatalism, but even in that context, there seems to be little sign of actual happiness in Chaucer. Troilus and Criseyde seems to show a narrator constantly struggling against his material, but forced to accept its depressing nature. The Knight’s Tale combines ironic humor (very common in autistics) with depressive fatalism:

“This world nys but a thurghfare ful of wo,

And we been pilgrymes, passynge to and fro.

Deeth is an ende of every worldy soore.”243

Chaucer has a strong tendency in his works to portray himself as a man inexperienced in love244 — “indeed, from what he says about himself one would get the impression he was a bachelor.”245 This seems strange coming from a middle-aged man whose marriage lasted for at least twenty-one years.246 But autistics have a horrible time finding love companions. It is true that there are a lot of sensuous descriptions of women in Chaucer’s writings,247 but there are plenty of men who know what women look like without having actually had any success with them. Could Chaucer have been married but lonely? It would fit his writings — observe, for instance, that he is not accompanied by a wife on his journey in the Canterbury Tales. (To be sure, his wife was dead by the 1390s when the Tales were written.) “There are indications that Chaucer’s married life was not happy, that he was cynical about marriage, and that he was much in love with another woman.”248 And there is a wild speculation (although that is all that it is) that his son Thomas was actually John of Gaunt’s illegitimate son,249 as if Chaucer’s marriage with his wife was not very solid.250

There is a curious and disturbing record from 1380, in which the family of Cecilia Chaumpaigne released Chaucer from a charge of raptus — which might mean rape, or possibly abduction or something else. We don’t know what Chaucer was actually accused of doing,251 or even if he was the primary defendant. Many have suggested that Chaucer’s son Lewis, for whom A Treatise on the Astrolabe was written, was the offspring of this union.252 There is, however, no supporting evidence of this — and if the dating of the Treatise is right, Lewis may not have been old enough to be Cecelia’s child anyway. It doesn’t matter; we must face the possibility that Chaucer was charged with something that might have been sexual violence. But was that his intent? At this time, defendants were not allowed to testify in their own behalf,253 so if Chaucer said something that was misunderstood, and was charged as a result, he would have no chance to explain it. And it is infamous that autistics frequently have their sexual intentions misunderstood — and misunderstand the intentions of others. (If you think that the mere fact that Chaucer was a great writer means that his spoken intentions would not be misunderstood, all I can say is, there are plenty of autistics who can write wonderful descriptive prose who can still mess up when speaking on emotional subjects!) My wild guess — I grant that there is no supporting evidence — is that he thought she had agreed to go with him, perhaps to marry someone Chaucer thought she should marry, but that she had not in fact agreed. So he hauled her off — not necessarily violently, because she may not have understood what he was proposing — and she accused him of abducting her.

In The Book of the Duchess Chaucer speaks of an illness — something that sounds like lovesickness — that has afflicted him for eight years.254 This might simply be conventional, but eight years before the composition of The Book of the Duchess would be when Chaucer was in his late teens — a time when many people suffer their first real love affairs. Most people, of course, do not suffer lovesickness for eight years; after a few years, they get over it. It is very different for autistics. They may not have many close relationships, but the relationships they do have do not seem to end. They don’t “get over” lost friendships or loves, or at least do so extremely slowly. So Chaucer, if he had had a failed relationship, might well still be suffering over it eight years later.

“[O]ne fault that Chaucer never overcame [was] a tendency to parade knowledge in the form of intrusive learned allusions.”255 Autistics often have this problem — they really want to talk about whatever it is that they know a lot about. Just witness all the silly footnotes in this document....

Scholars looking at Chaucer’s administrative work have concluded “that he was not a very good administrator [and] that he was far from thrifty.”256 Chaucer “was in the habit of living comfortably and seems to have spent with abandon.”257 “It... appear[s] that Chaucer was irresponsible about money. He was an expert accountant, who had kept the books of the Customs for twelve years and handled the enormous accounts of some dozen major project when he was Clerk of the Works, but in his private finance he seems to have treated money as if it were not real.”258 A lack of administrative skills is quite normal for autistics (whose decision-making abilities are frequently affected by their condition), and poor money management skills can also arise from autism.

Chaucer’s father John seems to have been a successful and fairly substantial businessman;259 Geoffrey was primarily a courtier, clerk, government functionary, and ambassador. Chaucer’s parents were vintners — wine importers and sellers.260 The very name “Chaucer” derives from their occupation. Yet there is no sign that he ever had anything to do with that work — indeed, one of the relatively few records of his personal life is of him transferring family property to another vintner.261 This is extremely unusual in a time when most children followed their parents’ occupations. Admittedly being a courtier offered perhaps a greater chance of advancement, but it’s still unusual to see a merchant’s son farmed out this way. Could there have been something unusual above Chaucer as a boy which caused his parent to seek another job for him? Autistics often lack the skills to manage their own businesses.

“Chaucer hates sham and pretense,”262 and autistics almost universally loathe these as well.

In The House of Fame, there is a section where people are awarded fame or its lack by the goddess. The awards are announced by the wind-god Eolus by blowing the golden trumpet “Clear Laud” or the black trumpet “Slander.” The sounds of these trumpets are not described as sounds but in terms of other senses: “The black trumpet is said to be uglier than the Devil himself, its sound bursting like a ball from a cannon with black and colored smoke billowing ever larger and stinking like the very pit of hell. The sound of the golden trumpet smells, by contrast, like pots of balm among baskets of roses!”263 This sounds like a description by someone with synesthesia — and synesthesia is two to three times more common among autistics than among the general population; some estimates suggest that close to one in five autistics experience it.

Chaucer had a hard time finishing things — a very autistic trait. It is easier to list the books he finished (The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame, and Troilus and Criseyde)264 than to catalog those left undone. “In the context of Chaucer’s work as a whole, Troilus and Criseyde stands out by reason of its scale and its essentially finished appearance. It is the one truly major work that he carried through to the end.”265 Chaucer’s translation of the Romance of the Rose — if it is his — is fragmentary.266 A Treatise on the Astrolabe is clearly incomplete, and there are hints that Chaucer started and stopped at least once267 before abandoning it completely (because the child to whom it was addressed was uninterested?). Anelida and Arcite didn’t reach a conclusion.268 The House of Fame has a “non-ending.”269 The Legend of Good Women contains only about half the promised stories and does not appear to have been completed270 — indeed, in the surviving copies, it seems to break off just a few lines before the end of a tale! The Canterbury Tales, although it has a beginning and an end, is unfinished. The Cook’s Tale is a fragment;271 the Squire’s Tale is either unfinished or incompetently interrupted, and there are no tales for the Ploughman, the Knight’s Yeoman, and the Five Guildsmen.272 Enough links are missing that we do not know the intended order of the tales, and some scribes took it upon themselves to create spurious links.273 There is even one instance of a scribe creating a whole new ending, as well as inserting a tale to go with it.274 Did Chaucer die before he could complete the work, or did he abandon it?275

No matter what the reason for the incomplete state of the book, the way Chaucer wrote the Tales is interesting. Ordinarily we would expect a major literary work to be planned as a whole but written primarily sequentially. If it is unfinished, it should simply peter out (as is the case with most of Chaucer’s other incomplete works) Not the Tales! Even though a few of the pilgrims never get to tell their stories, most tales are present. What is lacking is the structural scaffolding to connect them; this is why the Tales are presented as a series of fragments. “[I]t is striking how — as the fragments of the Canterbury Tales stand — Chaucer seems to have been working out towards the continuity of the Tales as a whole from local unities....”276 There are hints that The House of Fame was also assembled by this sort of accretion.277 This is a typical autistic approach: Start with the details and work to the big picture. Indeed, it is one reason autistics have so much trouble accomplishing things: it’s too hard to escape the details!

Chaucer’s questioning of the Black Knight in the Book of the Duchess is “as literal-minded as a computer.”278 “Chaucer shows little interest in allegorical interpretation or hidden meanings. He is a literalist, and for him the beast-fable tends to become a fictional exemplum....”279 He shows this from very early on. The Book of the Duchess, his earliest substantial work, is a dream vision based on allegorical models, but in Chaucer’s handling of the material, “Allegory disappears.”280 Similarly, The Parliament of Fowls has an artificial setting of birds gathered on St. Valentine’s Day in a garden281 — but most of the birds are interested only in following their natural impulse to mate.282 Autistics are famous for being very literal. In fact, many cannot understand fiction very well — which makes it interesting that Chaucer, although capable of taking an existing tale and making it far richer, rarely created a plot.

Chaucer portrays himself several times in his writings — as a pilgrim in the Canterbury Tales, as a dreamer in the House of Fame, and so forth. In all these instances, he portrays himself as rather simple-minded. Even in the extremely early Book of the Duchess, “his narrative persona — untutored, self-deprecating, even foolish — is fully realized and consistent.”283 In The House of Fame he “caricatures himself as not just dim-witted by magnificently dim-witted.”284 There is one, and only one, record of what Chaucer’s personal speaking style was like — a record, not verbatim but based on his actual words, at a trial in which he was a witness. “His little narrative displays the Chaucerian technique of putting words in others’ mouths and himself playing the naif; his use of it on the witness stand suggests that it was a habit of mind, a part of his personal style.”285 This is a tremendous amount to read into what was after all a very short bit of testimony, so the interpretation should be taken with a grain of salt — but autistics often find it very hard to take compliments and are likely to be anything but complimentary about themselves.

Chaucer’s sympathy with women was considered noteworthy in his time.286 A modern author goes so far as to declare that “Chaucer was what may be called an androgynous personality,”287 and believes “he was the first male writer since the ancient world who was successfully to see into the mind of a women.”288 Autistics are noteworthy both for having traits of the opposite gender and of being sympathetic with the other gender — all of my close friends have all been of the other gender, and this apparently is rather common.

Chaucer is noteworthy for the ironic humor of his writings — indeed, it sometimes seems to me that this is one of the biggest reasons he is not held in even higher esteem; great writers are expected to be serious. But this humor is not in evidence in his early writings: “Little of the muted humor in The Book of the Duchess promises the extravagant comedy of his later years.”289 For autistics, humor is often something learned — I taught myself to have a sense of humor in my early twenties.

And Chaucer’s humor sometimes has a taste of the logical humor of that greatest of nonsense writers, Lewis Carroll, who was almost certainly autistic. Consider Pandarus, who is the victim of an unrequited love. Medieval belief was that an unrequited love caused loss of appetite — so Pandarus, whose love is only half serious, says that he has no appetite on half the days.290

Chaucer tells several “bird tales”: the Nun’s Priest’s Tale of Chauntecleer and Pertelote; the Parliament of Fowls; an eagle carried the poet around in The House of Fame. It has been suggested that he has something of a “thing” about birds — as many autistics have a thing about certain animals. This is probably overblown, but “[i]t all speaks less of Chaucer’s affection for birds (which, like Swift’s for horses, was probably restrained) than of his disaffection for human beings”291 — and that is extremely typical of autistics.

Chaucer also shows a certain ability to think outside standard human viewpoints, “[a]s in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, where a rooster’s notion of beauty sometimes jars rather sharply with our own (VII.3161).”292 It doesn’t really matter if Chaucer is right about what one chicken would consider desirable in another; the point is, he sees things differently. Most autistics do — and some, indeed, owe their success to their ability to think this way. Temple Grandin is famous for her ability to design cattle enclosures that the animals are comfortable with — she sees the enclosure as the animal does. Chaucer too seems to think that way.293

Chaucer wrote four poems about dreams (apart from Chauntecleer’s dream in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale), and makes multiple references to insomnia.294 Conventional, yes — dream-visions were commonplace at this time295 — but Chaucer sounds as if he has really experienced this:

I have gret wonder, be this lyght,

How that I lyve, for day ne nyght

I may nat slepe wel nygh noght;

I have so many an ydel thoght

Purely for defaute of slep....296

The large majority of autistics have sleep problems — usually insomnia or sleep apnia.

That same introduction to the Book of the Duchess gives clear evidence of depression; it reveals “the feeling that nothing is dear or hateful to him; that ‘al is ylyche good.’”297 It is estimated that about eighty percent of autistics are depressive to some degree.

Chaucer several times confesses to a great love of books and reading298 — in the “G” prologue to The Legend of Good Women he admits to owning sixty books.299 At a time when all books were hand-copied onto parchment or very expensive paper (England at this time did not have a single paper mill; the first was founded by John Tate between 1490 and 1495300), this must have represented an investment of several years’ income at least. A love for books that strong reminds me of an autistic’s “special interest.” And most high-functioning autistics love to study and read.301

Autistics are noteworthy for their nitpickiness. And Chaucer’s complaint about his scribe Adam is extraordinarily harsh:

But after my makyng thow wryte more true

So ofte adaye I mot thy werk renewe,

It is to correcte and eke to rubbe and scrape,

And al is thorugh thy negligence and rape.302

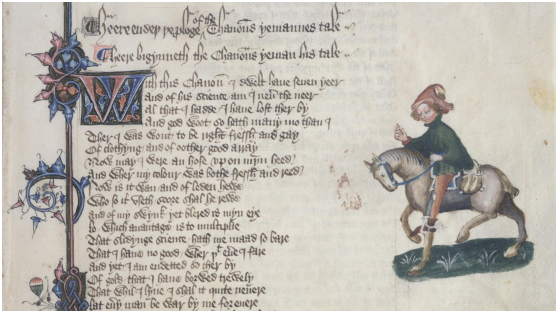

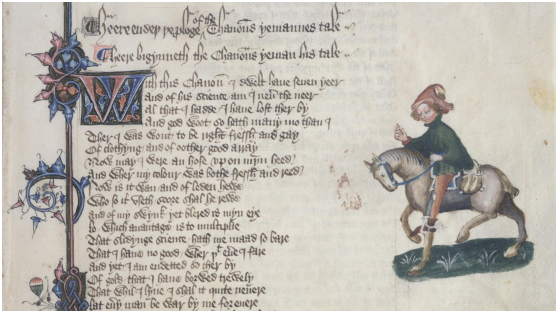

Image of the beginning of the Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale in the Ellesmere Manuscript,probably by Adam Pinkhurst, showing the correction to the to the prologue’s subscription. The correction is the top line of the cropped and reduced image. The painting of the yeoman is also shown. Image from the Digital Scriptorium: San Marino, Huntington Library, Ellesmere 26 C 9. http://www.digital-scriptorium.org.

We of course don’t know how good or bad a copyist Adam was.303 Perhaps Chaucer’s words were justified. But then why would Chaucer have hired him? More likely Adam was a perfectly competent copyist who — like all scribes — made occasional mistakes, and Chaucer the perfectionist blew up about it.

There is strong evidence that Chaucer was a bit on the heavy side,304 and autistics often dislike exercise and physical activity; many are physically clumsy. (Which makes it at least mildly interesting to note that Chaucer, as a young soldier, was taken prisoner in the French campaign of 1359/1360,305 and had to be ransomed for the substantial sum.306 He ended up disliking war enough to write “ther is ful many a man that crieth ‘Werre, werre!’ that woot ful litel what werre amounteth.”307 Also, he was robbed three times in 1390, apparently in the space of four days,308 of a total of about £40;309 could physical ineptitude have contributed? We have no good evidence either way.)

Just before Chaucer-the-narrator launches into Sir Thopas, the Host says to him:

“And lookest as thou woldest fynde an hare,

For seyde thus, ‘What man artow?’ quod he;

‘Thou evere upon the ground I se thee stare.”310

Chaucer-the-narrator is not Chaucer-the-author, but the narrator sounds as if he rarely looks people in the face — which is, of course, one of the classic signs of autism. It has also been noted that Chaucer, in the General Prologue, devotes much more attention to the pilgrims’ noses and mouths and even foreheads than eyes.311 This is perhaps the style of the time — but autistics, because they don’t look people in the eyes, have a hard time describing eyes.

Most authors in this period had patrons, and dedicated books to them — it was how they made their livings. Chaucer didn’t do this; “he drew the line at the obsequiousness that went with the acknowledgment of patronage.”312 The Book of the Duchess was obviously implicitly dedicated to John of Gaunt — but it doesn’t actually say that. Troilus and Criseyde is dedicated to John Gower and Ralph Strode, who could not pay him for his work. There are no dedications at all to noble patrons. Admittedly the “Complaint to His Purse” is an appeal to Henry IV313 — but it’s an appeal, not a dedication. To be sure, Richard II (the king during Chaucer’s most active period) seems to have been no patron of literature314 — but surely Chaucer could have found someone had he tried. Clearly he didn’t. Autistics often have a tendency toward democracy,315 and they hate “sucking up.”

It has been suggested that Chaucer was concerned with the philosophical question of how people communicate with each other; John Gardner thinks that the first three Canterbury Tales, The Knight’s Tale, The Miller’s Tale, and The Reeve’s Tale, offer three views of how the world works, which cannot all be correct. “Who is right, the Knight, the Miller, or the Reeve? And if an answer is possible, how do we convince the drunken Miller or the irascible old Reeve?”316 I’m not sure I believe this, but if ever there was someone who would believe that human beings cannot really communicate with each other, it will surely be an autistic!

Chaucer has a curious tendency to increase the element of chance or fate or luck in his stories.317 For example, in his source, Pandarus arranges for Troilus to display himself before Criseyde; in Chaucer, this happen only after he has caught Criseyde’s eye quite by accident.318 This is a very subtle point, but it seems to me that chance plays a much greater role in the lives of autistics. If they make a good friend early in life, they are more socially able; if they are exposed to the right stimuli, they may find a good career; if given the right opportunity, they may become brilliant in a field. But if the chance doesn’t arise, they may fail utterly. Success and failure balance by a hair. This seems to be Chaucer’s philosophy also.

In addition, in all these things, he seems to seek an orderly explanation for what happens — even if the explanation is only the actions of the planets.319 The tendency to seek mechanical explanations even for human behavior — for seeking to understand behavior as resulting from measurable causes — is characteristic of autism.

Chaucer’s interest in science is notable;320 “the poet was well acquainted w