Reaching

Washington on May 5th, I made preparation to cross the Spanish lines and

re-enter Havana City on secret service. Finding however, that an army of

invasion would leave for Cuba in a few days, I hurried to Tampa to join the

Fifth Army Corps. The regular army was then mobilised, and outwardly all was in

readiness for a forward move.

General Wesley Merritt, then the only West

Point general officer in the United States Army, was named for commander of the

invasion, and when his appointment to lead the Philippine expedition was

announced, it was universally supposed that General Miles would take the army

to Cuba. But to the surprise of every one, General William R. Shafter was

placed in command of the forming Cuban expedition. An officer weighing

considerably more than three hundred pounds, and suffering from gout, seemed

the last man to lead an army into a difficult country like Cuba, where the

activity and intelligence of the leader could do much to overcome the obstacles

of the country, and mitigate risks to the health and life of those exposed to

such a climate.

Shafter’s appointment though, was a mere

indication of the lack of system in the War Department apparent at Tampa where

confusion reigned. The size of the army was increased sevenfold by a mistaken

stroke of the pen; and since the available transportation facilities under the

Stars and Stripes could not have carried more than 25,000 men from the coast,

the Administration is frequently blamed for not first devoting its entire energies

to securing the logistics and equipment of a small army for service, before the

vast resources of the National Guard were called upon, and the department

paralyzed by the immense mobilization.

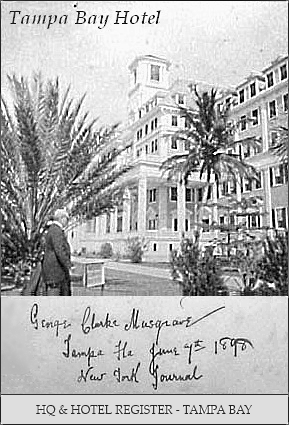

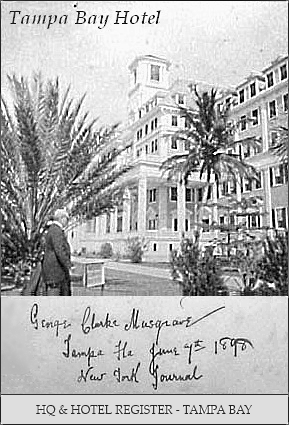

Tampa, assuredly, was not an ideal spot for

the preparation of an army of invasion. The white Florida sand made good

camping-ground; but though drier, the climate is scarcely less enervating than

that of Cuba. The great drawbacks, however, were the limited railway facilities

and the fact that everything in Tampa was expensive. This ensured a great

hardship on officers and men, who frequently were forced to purchase

necessaries of food and clothing that the commissariat should have provided. Despite

this exorbitance, though, life was tolerable in the palatial Tampa Bay Hotel,

the great winter resort which became army headquarters. Here the band played at

night in the Oriental annex, under flourishing palms, and officers danced with

bright-eyed Cuban senoritas, a number of whom had fled from Havana.

Eager groups animatedly discussed the war.

The bronzed Indian fighters from the plains sharing their enthusiasm with the

young subs just from West Point, and the civilian appointees, swelling 'neath

their newly acquired rank and uniform. When Colonel Roosevelt's Rough Riders

arrived, it was distinctly refreshing to find the sons of millionaires and

professional men of prominent families serving as troopers in the ranks with

cowpunchers, packers, and “bad men” of the West, all actuated by the same

patriotism, and all deserving honour commensurate with their individual

self-sacrifice.

Gathered in or around headquarters at the

Tampa Bay Hotel were considerably more than a hundred war correspondents and

artists, representing newspapers from every quarter of the globe. Evidently

Lord Wolseley's idea that the “drones of the Press” were the curse of modern

armies was not shared by the war lords of Washington. It was surprising to find that the vast

majority of correspondents, even those representing great New York dailies, had

never seen a shot fired in anger, and were absolutely ignorant of military

affairs. There were, of course,

exceptions and London sent some tried veterans, among them; Robinson, Wright,

Sheldon, McPherson, Hands, and Atkins; but many held passes who would never be

permitted to accompany an army in the field by the British War Office. The rigours

of home camps soon proved too great for much of this impedimenta, and it was a

greatly diminished but very fit body of Press knights who finally landed in

Cuba.

Hundreds

of expatriated Cubans living in Ybor City formed themselves into companies of

volunteers and, swelled by natives from all parts of the country, three strong

contingents were raised, commanded respectively by brave old Lacret, who had

slipped over from Cuba a few weeks previously, and Generals Nunez and Sanguili.

Colonel Janiz, the brave little doctor of Camaguey, was now his chief of staff.

Karl Decker, Herbert Seeley and I were honorary members, and among other

officers I was delighted to find young Mass, now a major, Frank Agremonte,

Aguirre, and other brave fellows whose past services in Cuba and consequent

sufferings in Spanish prisons had by no means deterred them from responding

again to their country's call. General Nunez was joined by Colonel Mendez, two

sons of the Morales family, and two New Yorkers, Thorne and Jones, all of whom

did excellent service later in Cuba. Dr. Castillo took charge of the “Florida,”

and landed the expeditions safely.

The military authorities punctiliously

enforced trivialities to the letter, and it was surprising to see the laxity

and consequent disorder in more important matters. Sanitation and the water

supply of the camps seemed a secondary consideration; and the issue of rations

and suitable outfits to the army would have discredited a staff of school-boys.

The officers of the regular regiments smiled grimly, but could say nothing.

Seven miles of freight cars were stalled in the sidings between Lakeland and

the Port. The stores had been rushed forward indiscriminately, no manifests

were provided, and no specific attempt was made at headquarters to evolve order

from chaos. A few details of intelligent non-commissioned officers could have

gone through the cars and tabulated their contents; but if beans were wanted, a

search was made until they materialised, and the same cars would be overhauled

by men searching for beef or tomatoes later in the day. Thus only the most

necessary stores were brought to light, and tons of provisions, delicacies for

the sick and medical stores were never unloaded.

General Shafter's force was ever sailing “tomorrow”

until “manana” took on a Spanish significance. The waiting seemed endless but

the order for a general advance at last arrived on June 5th. Its promulgation

at 10 pm. is history; this was war and it emanated from the commanding general

that “All who were not on board the transports by daybreak would be left

behind.”

Officers and correspondents dashed off to

their quarters to pack, dress, and catch the 11 o’clock train for war. It

arrived at 5 the next morning and we reached the embarkation pier at 6 am.

Whole battalions were moved in the rush. Regiment after regiment had hurried

down to the narrow pile dock, which was soon packed indescribably with men and

baggage. Troops at the extreme end of the pier were afterwards assigned to

transports moored at the shore end, and vice versa. The embarkation resembled

the sailing of a vast excursion party rather than a military movement. With the

capacity of each transport, and the roster of each regiment before him, the

youngest officer could have made effective assignment and saved such dire

confusion, which took two days to untangle, and entailed much sun-exposure and

hardship on the soldiers. But toward evening, June 7th, all was ready.

Boom! went a saluting gun, and away went

transport after transport; the bands playing, the troops, relieved from the

tedium of the wait, cheering as only such enthusiasts can cheer. But a gunboat,

previously a private yacht, had sighted two tramp steamers, and from

unexplained reason, taking them for Spaniards, showed a clean pair of heels to

Key West with the tidings. When this erroneous news was cabled to headquarters,

the order to:

! Stop the Expedition !

was sent

urgently from Washington. The leading transports were headed off far down the

bay at this time, and only recalled after a long chase by the “Helena”. A weary

wait ensued and the men, cramped on the vessels, which were fitted and filled

like cattle-ships, grew sick with the delay. The water grew stale; the lack of

exercise, and the foul air of the crowded holds in the fierce semi-tropical

heat, soon affected the troops. The halt laid the foundation of many a

subsequent death, beside the loss of a dry week in Cuba.

One week later we sailed. On the 13th the

flag ship “Seguranca” signalled the start; and with colours flying and bands

playing, the vessels glided out to mid-stream and dropped down toward the sea.

As the battery on shore boomed out a farewell salute, the soldiers swarmed to

the deck and rigging, and the air was rent with a shout of triumph from sixteen

thousand throats. The cheers were taken up on shore and echoed and re-echoed in

pine forest and everglade. They were not evoked only by the usual zest for war

shared by all men, the savage lust to fight which lies dormant in the piping

times of peace. Those troopers knew they had a mission to fulfil. They

remembered the blackened wreck in Havana Harbour, and the sailor comrades

sleeping in that foetid slough; they thought also of the women and children

crying aloud for deliverance from starvation and despair, and of the ragged

patriots fighting for liberty as their own fathers had fought.

Petty politicians have used the war for

their own purposes, thimbleriggers have not been idle; but to the close

observer it was evident that the war was a war of the people, the will of the

multitude, inflamed perhaps by much exaggeration and misrepresentation, but

nevertheless exerted for a just purpose when unvarnished facts stand forth.

Twenty hours after the start was signalled

we rounded Dry Tortugas, and in double column the fleet headed Cuba-wards,

flanked on either side by the guard of warships. The massive cruiser “Indiana”

held to the shore side, while the aggressive torpedo boat “Porter” dashed

inshore at intervals, on the lookout for any lurking gunboat of Spain that

might emerge on a forlorn hope, sink a transport, and meet the inevitable fate

gloriously. The “Annapolis”, “Bancroft”, “Castine”, “Helena”, “Morrill”, “Manning”

and “Hornet” guarded the fleet of transports on the voyage, with the “Detroit”,

“Osceola” and “Ericsson” acting as scouts.

The first land

sighted was the sandy loam on Cayo Romano, and as the sun set in tropical

suddenness, a fire flickered from the summit and was answered by a second flare

on the distant heights of Cubitas: a message from the watchful guardia costa to

the beleaguered Cuban Government, which has meted isolated justice in spirit

rather than in letter, that the day of Cuba's triumph was at hand.

We had two alarms: three Spanish gunboats

came up boldly, but dashed into Nuevitas when the “Osceola” steamed out to

engage them, and later mysterious vessels sighted at night near Lobus,

disappeared in the darkness as the warships raced to meet them.

The stoutly built British lighthouses

fringing the Bahama Isles, alone broke the monotony of sea and sky after this,

and as the three and one-half days' trip became lengthened into six days and

seven nights, every one grew heartily sick of slow travel and cramped quarters.

A call was made at Man of War's Bay, Inagua Isle, a little-known British

possession lying midway between the extreme points of Cuba and Haiti and, after

passing through the Windward Passage, the mountains of Santiago at last loomed

into view.

Everything was quiet and peaceful, the

transports lay to off Morro Castle, far out of range, and nothing but tiny

clouds of smoke marked the presence of the blockading fleet, hidden below the

dip of the horizon. For twenty-four hours we lay there. General Shafter joined

Admiral Sampson, and they landed at Asseredo to hold conference with General

Garcia.

On June 22nd plans were perfected, and the

transports headed to Daiquiri, sixteen miles east of Santiago. Here the Jaragua

Iron Company own an iron pier for loading the ore, and at an early hour, as the

warships drew near, a great column of smoke and flame went up: the Company's

great storehouse and the township were fired by the Spaniards. As the garrison

evacuated, the fleet bombarded the forts and road, checking the advance of some

Cuban soldiers, mistaken for the enemy. At 10 am. boats were lowered and the

first regiment, the 8th Infantry, landed without opposition. Horses and mules

had to swim ashore, and all the men landed in a heavy surf in small boats, and

not until the next evening had the cavalry and Lawton's brigade disembarked.

The landing of the army was picturesque and

spirit-stirring. As the sun rose above the mountains, a flood of lustre was

thrown over the fleet of transports and massive warships, lying off shore on a

sea of clearest blue. Away toward Guantanamo, the water shone like liquid gold,

the waves washing over the base of the distant promontory in white cascades as

the regular undulations were broken by the rocks. The appearance of the

romantic shore was heightened by the debarking troops, forming up on the yellow

beach, their arms glistening bravely in the sun, while just above them lay the

little town backed by the lofty Sierras, the grim volcanic cliffs stretching

westward, a dividing line between the expanse of sea and sky.