Our

landing continued without molestation. On Thursday 23rd a distant rattle of

musketry wafted over Los Altares, six altar-shaped foothills, and huge columns

of smoke crept up against the sky line. The Spaniards were burning the small

towns and withdrawing into Santiago. General Lawton, with the 1st and 22nd

Regular Infantry, 2nd Massachusetts, and detachments of the 4th, 8th, and 25th

Infantry, pushed ahead into Siboney, finding it already occupied by Cubans under

General Castillo, who had attacked the rear guard of Linares, as they were

firing the town. The Spaniards fled, leaving stores and ammunition intact. They

tried to destroy the railroad as they retired, but Colonel Aguirre and some

Cuban cavalry followed them up, and the Imperial troops continued their flight.

At Aguadores, which was strongly garrisoned, the railroad bridge over the creek

was blown up with dynamite, to prevent our direct advance along the railroad.

The country within nine miles of Santiago

was now in our hands. The base of operations was moved from Daiquiri to

Siboney, a pretty little town, inhabited by the employees of the Iron and

Railroad Company. General Linares had made preparation to vigorously oppose a

landing here, and two almost perpendicular cliffs were terraced with trenches

carefully masked from top to bottom. He hoped the troops would walk into this

trap when they found the town seemingly deserted, and he could then open a

hidden fusillade from either side with open country behind for retreat. A few

searching shells from the fleet soon caused him to alter his decision, and the

troops evacuated this stronghold, Commandante Billen being killed by a chance

shell.

The warships continued bombarding Aguadores,

and the Spaniards replied vigorously. One shell struck the “Texas,” killing

Ensign Blakeley, and wounding five others dangerously, and the gunboats that

could be spared from the blockading squadron were unable to silence the coast

batteries.

General Shafter remained on the Seguranca,

with his plan of campaign. General Wheeler assumed command on shore, and

conflicting orders resulted. General Chaffee's Brigade was ordered to form the

advance in conjunction with Lawton's division, and reached Jaragua at dusk on

the 23rd. General Young's cavalry brigade, with General Wheeler, then passed

these outposts and advanced to Siboney. The Cubans reported the enemy in force

at Guasimas, and after General Wheeler had reconnoitred the position with

General Castillo, he ordered the cavalry to attack at daybreak. At 4 am. the

Rough Riders marched over the foothills by a thickly wooded trail, any section

of which invited ambuscade and annihilation, had the Spaniards possessed

initiative.

General Young, with the 1st and 10th Cavalry

and four Hotchkiss guns, advanced along the main road. The enemy, neglecting to

attack either force separately, held a position on a plateau where the trail

and road converged. General Rubin entrenched his forces in a disused Bacardi

distillery, with rough trenches built at an angle obtuse to the approaches.

Three companies of the Puerto Rico Battalion held his right, commanding the

main road, while opposing the Rough Riders, Major Alcaniz commanded half a

battalion of the San Fernando Infantry; two companies of the Talavero Regiment,

a company of engineers, and two gun detachments held the centre. General Young

deployed his men without discovery within 900 yards of the Spanish position.

The Rough Riders, though, advancing down the trail, were met with a terrific

fire, which checked them in some confusion; Captain Capron, Lieutenant Fish,

and several men being killed and many severely wounded. The raw volunteer

troopers, however, behaved splendidly. Colonels Wood and Roosevelt threw out

their troops in skirmish order through the chapparal. The regular cavalry had

extended their left flank, effecting a junction with the Rough Riders.

A semi-circular line of attack was thus

formed, but owing to the dense undergrowth, the American fire could not be

effectively maintained until a series of advances, in face of a hail of

bullets, had brought the line to within 300 yards of the Spanish position.

Pouring in heavy volleys from their carbines, the cavalry then surged forward,

the enemy's right flank falling back in good order before the Rough Riders, who

were now enfiladed by Rubin's mountain artillery, and the infantry supports entrenched

along the ridge. In a few moments the fire of the regulars drove back the

Spanish left, and after Captain Alcaniz with the “Talaveros” bravely sought to

cover the retreat of the guns and the wounded, the entire force fell back in

confusion and withdrew to Santiago. They left but thirteen dead on the field,

and removed their wounded, which were many.

At the supreme moment Captain Taylor, who

had heard of the battle, came up with three troops of the 9th Cavalry. Several

companies of the 71st Regiment also hurried to the front, but these

reinforcements were not required.

Considering the disposition of the enemy,

the American loss was extremely light. From a total strength of 964 men,

sixteen, including Captain Capron and Lieutenant Fish, were killed, and fifty two

wounded. Majors Bell and Brodie, Captains Knox and McClintock, and Lieutenants

Byram and Thomas were severely wounded. Mr. Edward Marshall, the war

correspondent, was shot through the spine during the battle. The Rough Riders

gained unstinted praise for their bravery at Guasimas.

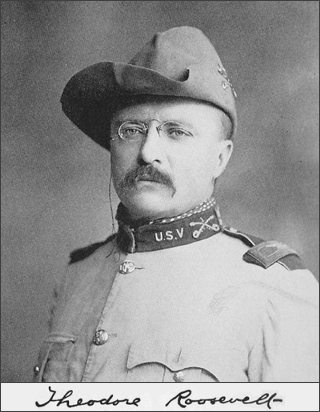

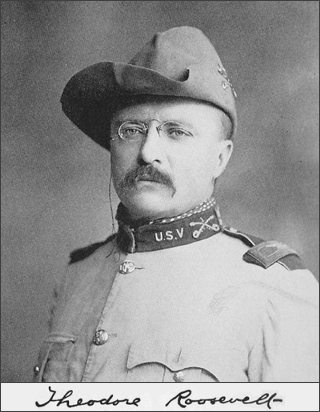

Colonel Roosevelt, after working incessantly

to place the navy on a war footing, raised the regiment of cowboys for scouting

in Cuba. Tenderfoot dudes, first tolerated, afterwards beloved, by the

ranchmen, flocked to the corps and an excellent camaraderie prevailed. He has

been charged with going to war to become Governor of New York but one of his

men, replying to this, said, “If the Colonel was looking out for a prospective

governorship, it must have been in Hades, for no one courted death more.”

I have

seen Colonel Roosevelt gently soothing his wounded, fearlessly leading a

charge, addressing meeting after meeting during his political campaign, and

quietly resting with his family. His every act is characterised by a fearless

sincerity, the sentiment of duty and principle of justice. The spirit of the

man is even more than any series of his acts; a man the nation can trust.

The disembarkation of the remaining

divisions of the army proceeded slowly, and many of the men, especially of the

71st New York, stood in the surf for hours in the tropical sun, seizing the

approaching boats and dragging them on shore through the breakers. Such

exposure in the tropics is a sure forerunner of fever. Perspiration poured off

the men, as they unloaded stores on the burning sand, and their overheated

bodies were repeatedly cooled as they plunged into the surf to drag the boats

to shore. That labour was constant for fifteen hours per day for a week, and

many a poor fellow unconsciously sowed the seeds of death, that soon stalked

grimly through the ranks.

The soldiers were under the impression that

tropical outfits would be issued for them in Cuba. They were still dressed in

heavy serge, the old regulation equipment, and many had only thin civilian

boots, which heat and salt water rendered useless. So few wagons had been

shipped that there was no transportation for their effects, and as regiment

after regiment was rushed to the front, the men, labouring in the sweltering

heat, discarded articles mile by mile, until they had nothing but the clothes

they stood upright in, and the route of the advance resembled the trail of a

retreating army. Besides kit, rifle, and ammunition, the troops were ordered to

carry three days' rations in their haversacks. They were marched at all hours,

invariably during the heat of the day, and suffered severely; only the splendid

physique of the American army made marches possible under such conditions.

The expedition landed just at the close of “el

verano de San Juan” (the summer of St. John), and but for the unfortunate week

of delay at Tampa, the advance could have been made in dry weather. The rains

restarted on the fourth day and the difficulty of transport increased. Yet

regiment after regiment was raced forward, when it was impossible to get

sufficient supplies to the front. The Cubans and cavalry brigade made efficient

outposts, and common-sense generalship would have mobilised the army first on

the hillside near Siboney, where the men could have been easily fed, and the

transport trains utilised to carry out supplies to an advanced base, protected

by the cavalry. When all was in readiness, even the day before the battle, the

army could have moved forward the eight miles toward El Pozo, and made the

attack, well fed, and with an abundance of supplies on hand to sustain it.

The army went to Santiago to accomplish a

stupendous task. A landing had to be effected on a hostile coast, artillery and

supplies moved forward through ten miles of difficult country, open at all

sides for surprise attacks from the enemy. Siege had to be laid to a

considerable city, well garrisoned, naturally entrenched with steep ridges, and

with a powerful fleet to assist in its defence. By negligence and blunder, the

land operations from first to last were a series of mistakes, any one of which

might have proved fatal to American arms. Victory was snatched at heavy cost,

but a victory that can be attributed alone to Providence; for had the morale of

the enemy been less impaired by starvation and disease, or had the fleet

remained in Santiago Harbour, the amazing valour of the American soldiers must

have gone for naught, and a reverse been entailed.

Owing to the unaccountable delay in

road-making during the dry days and the subsequent employment of improper

measures in repairing washouts and ruts with brushwood and sand, to withstand

the periodic downpours, even the light mortars could not be brought to the

front before July 9th, and not one of the siege guns was landed. What General

Shafter hoped to accomplish with an army thus equipped and moved against the

city, it is impossible to say. What would have been the result, even if

Santiago City had been carried by assault, if the Spanish fleet had turned its

heavy guns against the invading army, it is easy to foresee.

Ostensibly the army was to go to Santiago to

attack and destroy the batteries thus enabling the navy to enter the harbour,

remove the mines, and co-operate with the army on land in destroying the fleet

and capturing the city. To accomplish this, an advance should have been made

along the coast railroad under cover of the guns of the navy. Aguadores could

then have been captured, leaving only a short march across the foothills

between El Morro and Santiago. The shore batteries at the harbour mouth would

have been isolated and captured, and a combined advance made on Santiago by sea

and land, the army covered by the guns of the navy. General Shafter, in the “Century,”

says: “I regarded this as impossible.” Yet on July 2nd he wrote a note to

General Wheeler, asking if it were not feasible to capture the forts on the bay

to let in the navy, and on July 6th he still talked of it to his staff.

The army was sent up the most difficult

approach, against the strongest defences of the city; by superhuman exertion

the outlying positions were captured, but without sufficient artillery the army

could go no farther. They had the city surrounded, but must have withdrawn or

faced decimation by disease, without a chance to expel the fleet or assist the

navy in gaining entrance, had not the enemy steamed out to escape, and brought

on, from our point of view, the coveted result.

Castillo moved his Cubans forward to El

Pozo, where, under De Coro and Gonzales, they did efficient outpost work a mile

beyond the American lines, thus relieving the soldiers from much arduous guard

duty. Garcia brought 2000 insurgents, his Negro regiments of Cambote and

Barracoa, from Assedero, in government transports. Thoughtful Americans felt a

thrill of pity when they saw the unkempt and emaciated insurgents, who had

steadfastly endured three years' campaigning. Their march to the coast had been

terribly trying, and for several days they had existed on grass soup. Can we

wonder, then, that these ignorant Negroes were demoralised at the sight of hard

tack and bacon? They broke open the boxes and devoured the first square meal of

three years, with so much gusto that certain gentlemen looked on with disgust

and called them pigs, and energetic pressmen were speedily making copy on the “lazy

Cubans' hate of work and love of eating.”

Along the now disused trail between Daiquiri

and Siboney, overcoats and blankets were rotting by the wayside, and some of

the “boys” told the ragged pacificos of this discarded treasure which was

useless to the army. The poor wretches soon appropriated everything, but

unfortunately they applied this permission universally, and on subsequent

marches, when the men laid their packs by the roadside to collect later, they

frequently found them rifled. Ragged and ignorant as were Garcia's soldiers,

they did not steal and loot as charged, for theft is religiously punished with

death in the rebel camps. The Negro pacificos, many of whom were armed with

rifles shipped down at the time but were absolutely without discipline, had no

such scruples, and pilfered at every opportunity. It is impossible to fix any

standard of judgment for people in their condition. But they were not

insurgents, they were not Cubans. One-third only of the population of Cuba

before the war was coloured. Weyler killed off many of the whites in the West,

but the Negroes we saw around Santiago were no more typical of the Cuban race

than are the ignorant coloured squatters and cotton-workers of the Georgia

backwoods representative Americans.

Unfortunately, by the action of these Negroes,

the American troops soon lost the reverence they felt for the patriots'

struggle for liberty, since they had neither time nor opportunity to form a

broad and charitable judgment. Some of the very writers, who in Havana had

misled the public with faked stories of victorious insurgent armies sweeping

the Island, now found material at the expense of the Cubans in the expose of

the phantasms created by their own imagination.

Pressing forward to the outposts on June 26th,

we camped just above El Pozo, in a snugly thatched hut considerately erected by

the Cubans. The rains had restarted, and miasma hung over the valley like a heavy

pall, but toward evening the misty curtain was suddenly drawn aside, the skies

turned blue as if by magic, and a most glorious panorama lay revealed to our

wondering gaze. Santiago lay on a gentle ridge, alarmingly close, the minarets

of the ancient cathedral and the blue walls of the San Cristobel convent,

peeping over the graceful palms covering the valley. The sun was dropping

behind the heights of El Cobre, and shed a golden radiance over the peaceful

scene. The military hospital and barracks, standing at the edge of the city,

were plentifully bedecked with Red Cross flags, while before them, separated

delusively by an invisible valley, were the forts and blockhouses of San Juan.

The light uniforms of the soldiers lounging

around the blockhouses showed up plainly; they were apparently oblivious of the

approaching army. A few distant booms to seaward - the navy exchanging

courtesies with Morro - were the only evidence of war. Sunset was first

heralded by the Cuban bugler, but his puny notes were soon drowned by the

harmonious burst of trumpets, as the beautiful “retreat” of the American army

was sounded by the various regiments encamped at Sevilla, about a mile behind.

Then their bands burst into the Star-Spangled Banner; and stretched across the

heavens, with silver stars shining from a sky of blue and the crimson glare of

the setting sun intersected by white fleeced bars of cloud, the very spirit of

Old Glory was typified. It seemed that a spiritual hand had thus emblazoned the

heavens in omen of the flag so soon to float over that benighted land.

The army was camped near Sevilla where, despite

the rain and the sorry rations, the spirits of the soldiers were sustained by

the thought of battle. The light batteries were up, but we still looked across

at the enemy working on the defences before Santiago, while our guns were

parked, and the men worked on the roads. General Shafter arrived at the front

on July 29th, cursorily viewing Santiago from El Pozo. On the following

afternoon General Castillo and several American officers made a reconnaissance

from the war balloon, and in a pouring rain at 3 pm. a general advance was

ordered. Santiago lay to our direct front. General Lawton was to advance to the

extreme right, with the Second Division, comprising the brigades of General

Chaffee, the 7th, 12th, and 17th Infantry, General Ludlow, 8th and 22nd

Infantry and 2nd Massachusetts, and Colonel Miles, 1st, 4th, and 25th Infantry,

and two field batteries. After capturing El Caney, a fortified town menacing

the right flank, Lawton was to swing round and invest the north side of

Santiago.

The 1st Division, the 1st and 10th Cavalry,

and the Rough Riders, with three field batteries, were to capture the advanced

positions of Santiago at San Juan, and invest the city on the east. General

Duffield, with the 9th Massachusetts and 33rd and 34th Michigan and a force of

Cubans, was to advance along the coast and join the navy in a combined attack

upon Aguadores, menacing the left flank. If possible, he was then to move on

Santiago from the south. A semi-circular cordon would thus entirely encompass

the city. Garcia and his two thousand Cubans were expected to cover the entire

western edge of the bay and the extreme north, to prevent reinforcements or

supplies entering through either the Condella, Oristo, San Luis, or other

passes leading to the city.

It is inexplicable why a general advance

should have been ordered on the 30th. Lawton had seven miles to march to the

right, but the centre divisions had less than two. The sudden movement of the

army corps into the narrow trail retarded Lawton for several hours. The

remaining divisions might have remained in camp until daybreak, and marched the

short distance to the Pozo, dry, fed, and fresh for the assault. So congested

was the trail that darkness supervened before many regiments had advanced at

all, and at midnight the drenched troops lay down in the muddy road and rested

on their arms until daybreak.

Reveille on July 1st roused a wet,

bedraggled army from unrefreshing sleep. The troops lit fires with difficulty,

and the centre divisions roundly “groused” at the spoilt night that they might

have spent comfortably in camp. But the boom of Capron's first gun at Caney

sent a thrill through the ranks; discomforts were forgotten, and the tension of

anxious anticipation, the exultant, undefinable something of approaching

battle, dominated each one of us. With Creelman and Armstrong, I moved down

toward Caney, and turned to view the shelling of the citadel from the Ducrot.

This citadel resembled a French chateau rather than the Moresque forts of

Spain; but the guns made little impression upon it, and I rode back to El Pozo,

where Battery A, Captain Grimes, was entrenched on a ridge opposing San Juan.

Directly behind the guns the cavalry were at

ease, preparing a sorry breakfast. I remembered, at certain training manoeuvres

at Aldershot, that a field officer was disqualified for halting his men some

distance in rear but directly behind a battery during an artillery duel. Seeing

the guns about to open, I had the temerity therefore to warn one officer of the

danger, should the enemy's artillery reply. “We have our orders and cannot

move,” was the answer.

By the guns, Captain Grimes and Lieutenants

Conklin and Farr were ranging, the cannoneers stood by their pieces, and at one

minute to eight, No. 1 and 2 guns were loaded with common shell.

“Range 2500 yards!” The breech block was

closed with a snap, the trail of No. 1 gun was swung into position, and the

layer looked over his sights, depressing the piece a trifle.

“No. 1! Fire!” The report rang out; a shell

went screaming over the peaceful valley and burst at impact just beyond the

ridge, amid the cheers of the soldiers.

“Too much elevation! No. 2 at 2450. Ready!

Fire!” “Still a little high!” No. 3 gun sent a shell crashing below the

blockhouse.

No. 4 missed fire through defective pricking;

but in the second round each gun sent a shell hurling against the blockhouse,

and the enemy could be seen scampering to cover. With the range fixed, shrapnel

was implemented.

Up to the thirteenth round there had been no

reply, though we looked instinctively across the valley after each discharge.

Suddenly a tiny ring of bluish smoke circled through the air, and with a

vicious scream a shrapnel hurtled over the battery and burst just above the

heads of the crowd behind the hill. Men fell on all sides, and before the

surprised soldiers had recovered from their astonishment, another shell

exploded. With marvellous direction, shrapnel burst regularly just over the battery,

among the troops so wickedly exposed there. A group of Cubans were literally

blown to pieces, horses were killed, and then a shell burst before No. 3 gun,

killing two gunners. Helm and Underwood, instantly, fatally wounding Roberts,

and injuring every man in the vicinity. As I turned, blinded with dust, with

Scovel and Bengough, to seek a less exposed place, the grimy figure of Corporal

Keene loomed through the smoke, and with blood pouring from two wounds he

returned to his gun, which Michaelis, the son of a brave officer, and the only

one uninjured in the detachment, was coolly working as if on parade, while

Brown, a Harvard man, carried ammunition from the caissons.

There was a subtle fascination in watching

the three devoted officers, and the men of Battery A, standing exposed to the

sure and deadly fire, and answering shot by shot. Colonel Ordonez, the Spanish

inventor and artillerist, succeeded Colonel Melgar, commanding the artillery,

and had personally ranged the position with fearful accuracy. The enemy used

smokeless powder, and their battery could not be located, while the black

powder of our guns made a perfect target. After nine minutes of this effective

shelling, the Spaniards fortunately held fire, and thus the crowded troops

behind the ridge were able to move from their perilous position. Grimes fired fifteen

more rounds, and failing to evoke reply, he also ceased fire, and his men fell,

exhausted by their efforts in the hot sun. Below the hill Surgeon Quainton

worked heroically under fire with Dr. Church of the Rough Riders.

When the artillery duel had ceased, though

there was no indication that the enemy's guns had been silenced, the regiments

started to pour down the trail leading through the thickly wooded valley

intervening between El Pozo and the enemy's position on San Juan.

Lieutenant-Colonel McClernand, of the Fifth Corps, had ridden up with orders

from General Shafter for Generals Kent and Sumner to move their divisions

forward through the valley to the edge of the woods and there await orders. The

trail led down to the San Juan River, walled in on either side by impenetrable

bush. Just beyond the last ford the woods ended abruptly and a gentle grassy

slope led to the foot of the San Juan ridge, which is like a huge rampart

thrown up to defend Santiago. Extending along its whole length were trenches,

intersected with blockhouses, while below strong barbed-wire barricades were

stretched along the base of the hill. San Juan was the strategic key to

Santiago. Beyond was an intervening valley, with a gradual ascent leading up to

the plateau on which the city stands. It commanded the succeeding rows of

trenches on the hillside and the strongly fortified and barricaded outskirts of

the city, that rose like a wall along the next crest.

One moment's consideration of the topography

of this position will show that an attacking force marching down the wretched

trail to San Juan would be forced to form line of battle at the edge of the woods,

under a sweeping fire from trenches and forts, and after thus deploying, the

depleted force must advance across the open, against the fences, and storm the

hill. Such a course could but court extermination.

There are defined, strategic rules for

capturing such a position. Preparatory action holds infantry to cover with

artillery at the front, until the shelling has produced sufficient effect for a

general advance. The configuration of the ground seldom admits guns remaining

far in rear of the advance, but there is no justifiable hope in advancing

strong masses of troops against an entrenched position without preparatory

artillery action, and no assault should be ordered until the artillery duel has

silenced the enemy's guns and shaken the defending forces. A few hours shelling

would have demolished the blockhouses and cleared the trenches along the

ridges. Then, with rough trails cut branching from the road through the trees

to the edge of the wood, several columns could have emerged simultaneously in

the valley, formed line, and charged the hill with small loss, ready to face

the enemy's main position. General Shafter, however, intended that the columns

should advance quietly through the woods, and stand ready to make the charge

when the artillery had prepared the way and Lawton's Division had swung to

flank the position on the right. Possibly he thought the enemy would sleep in

the interim.

Into the unknown jungle the cavalry and

infantry advanced. The road was muddy, and in places only three could march

abreast, so that when the advance guard reached the first ford, the road was

choked with closely wedged men for considerably over a mile. The Spanish

pickets concealed in palm trees, in the valley, soon saw blue uniforms

advancing, and gave the alarm. Not certain of the strength of the force, the

Spaniards fired only a few desultory volleys, but as the vanguard came unseen

down the road, the captive war balloon was sent bobbing along in the very

advance, just over the tree-tops. It developed the fight the moment it drew

within range. Every rifle from fort and entrenchment blazed at once at the

silken globe; the artillery re-opened, and bullets and shells poured through

the tree-tops, dealing death and destruction among the men in the crowded

trail. By this time the cavalry were starting to deploy along the creek; but when

the wretched balloon had finally received its quietus, and sunk amid the curses

of the men stricken through its agency by an unseen fire, the enemy had exactly

ranged the line of the road, and were apprised that a general advance was

taking place. A withering fire was directed against the angle where the balloon

had disappeared and along the edge of the wood.

In a moment the insanity of the tactics

dawned upon the American army; not though the soldiers knew someone had

blundered. “Theirs not to reason why. Theirs but to do and die.” The whole

command would have been withdrawn, and the artillery allowed to prepare the

way, had not the trail been so packed that a retrograde movement would have

cost hundreds of lives, besides demoralising the survivors. A modern army,

composed of the finest men and material in the world, had been moved recklessly

into a death-trap, to be decimated by what proved to be a handful of

half-starved Spaniards.

Generals Kent, Hawkins, and Sumner held a

hurried consultation. Lieutenant Ord climbed a tree and viewed the enemy's

position far more effectually than a hundred balloons. General Hawkins crossed

the ford, and glanced upward at the ridges. In a few moments the leaders of

division, seeing retreat impracticable, decided to rush the position.

Lieutenant Miley, representing headquarters

where the commander-in-chief should have been, concurred in their view. Grimes’

Battery had reopened, and as there was imminent risk from our own shells

falling short, he sent orders to the artillery to cease firing while the troops

deployed. A heroic figure of six feet three, Miley stood at the ford,

encouraging the men, who moved over the stream into a hell of fire. Cavalry and

infantry were mixed, but the former deployed to the right, the latter on the

left. The men were ordered to reserve their fire and to lie flat on their faces

as they formed line. The San Juan River ran streaked with blood, for the dead

and wounded fell from its slippery bank into the water repeatedly.

Hawkins's Brigade, the 6th and 16th

Infantry, extended first; the 71st New York, who had suffered severely, being

ordered to support. Through misunderstanding these volunteers were halted and

lay down in the road beneath a galling fire, and Wikoff's Brigade, the 9th,

13th, and 24th Infantry, passed over them. Colonel Wikoff was killed as he

reached the head of the road. With magnificent coolness Colonel Worth of the

13th stepped forward to lead the brigade. He was shot down instantly. Colonel

Liscum of the 21st sprang in