VI

CARTER NOTCH

Its Mingling of Smiling Beauty and Weird Desolation

Sometimes, even in midsummer, there comes a day when winter swoops down from boreal space and puts his crown of snow-threatening clouds on Mount Washington. They bind his summit in sullen gray wreaths, and though the weather may be that of July in the valleys to the south, one forgets the strong heat of the sun in looking upward to the sullen chill of this murky threat out of the frozen northern sky. Thus for a day or two, it may be, the summit is withdrawn into cloudy silence, which may lift for a moment and let a smile of sunlight glorify the gray crags, and flash swiftly beneath the portent, then it shuts down in grim obsession once more.

At other times winds come, born of the brooding mass of mists, and sweep its chill down to the very grasses of the valley far below, but this shows the end of the portent to be near. The morning of the next day breaks with a bright sun, and you go out into a crisp air that sends renewed vitality flashing with tingling delight through every vein down to the very toe tips. The clouds that blotted out the summits with their threat of winter are gone, and the mountains leap at you, as you look at them, out of a clarity of atmosphere that one learns to expect where the hills rise from the verge of the far Western plains but which is rare in New England.

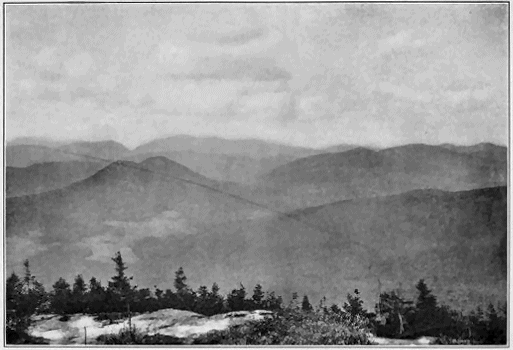

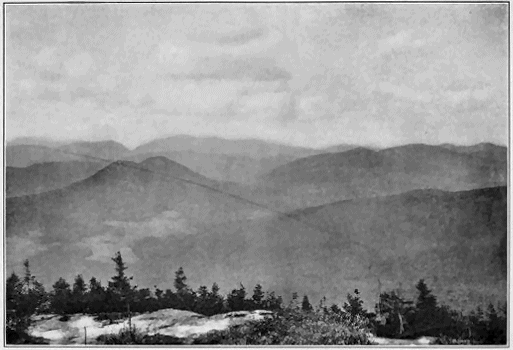

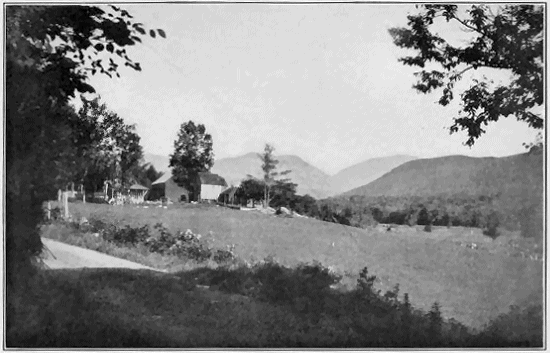

Carter Notch seen over Doublehead from Kearsarge summit

The mystical haze that has for weeks softened all outlines and magnified all distances till objects within them took on a vague unreality, is gone, and we see all things enlarged and clarified as if we looked at them from the heart of a crystal. And as with outlines, so with colors. No newly converted impressionist, however enthusiastic in his conversion, could paint the grass quite such a green as it shows to the eye, or get the gold in its myriad buttercup blooms so flashing a yellow as it now has. All through the soft days these have been a woven cloth of gold. Now the cloth is unmeshed, the very warp has parted, the woof separated and the particles stand revealed, a thousand million scattered nuggets instead, each individual and glowing, a sun of gold set in the green heaven of the meadow. The wild strawberries that nestled by thousands in the grasses so shielded that one must hunt carefully to see them, seeming but blurred shadows complementing the green, now flash their red to the eye of the searcher rods away. Here for a day is the atmosphere of Arizona, which there reveals deserts, drifting in from the north over the lush growth and multiple rich colors of a New England hillside country.

It is a scintillant country on such a day. The twinkling leaves of birch and poplar flash like the mica in the rocks far up the hillsides, the surface of each dancing river vies with these, and through the crystal waters you look down upon the bottom where silvery scales of mica catch the light and send it back to the eye. It is no wonder the early explorers from Massachusetts Bay colonies came back from the white hills with stories of untold wealth of diamonds and carbuncles to be found here. You may find these jewels on such a day at every turn, though they are fairy gems only and must not be covetously snatched, lest they turn to dross in the hand.

The meadows above Jackson Falls flash with this beauty from one hillside across to another, and through them winds the Wildcat River, luring the casual passer to wade knee deep in the grass and clover from curve to curve, always fascinating with new enticement till it is not possible to turn back. Nor are the fairy gems which the long, winding valley has to show confined to the sands of the river bottom or the boulders scattered along its way. At times the air over the clover blooms is full of them, quivering in the sun, borne on the under wings of the spangled fritillary butterflies that swarm here in early July. Above, the fritillaries have the orange tint of burnt gold, plentifully sprinkled with dots of black tourmaline, but beneath they have caught the silver scintillation of the mica-flecked rocks and sands on which they love to light when sated with the clover honey. These too are gems of the mountain world which, if not found elsewhere, one might well come many miles to seek. It is easy to believe, too, that the spangled fritillaries know the source of the silver beauty of their under wings and cunningly seek further nourishment for it. You find them hovering in golden cloud-swarms over bare spots of scintillant sand along the reaches of the river or in the paths of the roadside which rambles down from the hills with it, anon lighting upon this bare and shining earth to probe with long probosces and draw from the mica-flecked sand perhaps the very essence of its silvery glitter, for the renewing of their wing spots. The white admirals are with them, not in such swarms to be sure, but in considerable numbers, eager also for the same unknown booty. It may be that they too thus renew the silver of their white epaulets.

I found all these and a thousand other beauties on my trip up the Wildcat to its source in Carter Notch, through this region of mica-made fairy gems. They lured me from curve to curve and from one rapid to the next beyond, always climbing by easy gradients toward the great V in the Carter-Moriah range, whose mysteries, to me unknown, were after all the chief lure. The crystal-clear air out of the north, which had swept the gloom from the high brow of Mount Washington, made the mountains seem very near and sent prickles of desire for them through all the blood. On such a day it is a boon to be allowed to climb, nor can one satiate his desire for the achievement of heights except by seeking them from dawn till dusk. Little adventures met me momentarily on the way. Here in a mountain farmer's field was a great mass of ruddy gold, showing its orange crimson for rods around a little knoll. Yet this was but fairy gold as the gems of the Wildcat meadows are fairy gems, a colony of composite weeds which no doubt the farmer hates, but which produce more wealth for him than he could win from all the rest of his farm for a decade—if he could but gather it. The fritillary butterflies know its value and flock to it, losing their own burnished coloration in it, and the wild bees are drawn far from the woodland to it by its soft perfume. To come suddenly on this was as good as discovering a new peak.

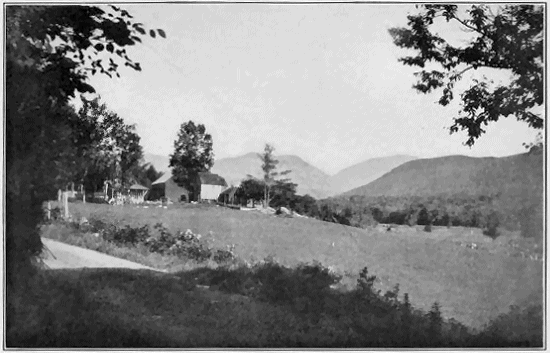

"Always climbing by easy gradients toward the great V in the Carter-Moriah Range"

To hear a tiny shriek in the wayside bushes and on search to rescue a half-grown field sparrow from the very jaws of a garter snake, sending the snake to gehenna with a stamp of a big foot and seeing the fledgling snuggle down again into the nest with the others, was as pleasant as finding the way to a new cascade. But after all, the great lure of such a crystalline day is toward the high peaks. The Wildcat River has its very beginning in the height of Carter Notch, and its prattle over every shallow teased me to follow its trail back to this high source and see what the spot might be. To do this step by step with the falling water would be a herculean task, for the gorges down which it runs are choked with boulders and forest débris and tangled with thickets as close-set and difficult of passage as any tropical jungle. But there is no need to seek its source by that route. You may go within four miles of it by motor, if you will, up the good road from Jackson that finally dwindles and vanishes on the slope up toward Wildcat Mountain, but not before it has taken you through a gate and showed you the entrance to the A. M. C. trail to the top of the Notch.

All the way up to this point the outlook to the south has been growing more extensive and more beautiful. Black Mountain still lifts its broad ridge from pinnacle to pinnacle on the east side of the Wildcat, but Eagle Mountain, Thorn, Tin, and the little height between these last two have been dropping down the sky line till Kearsarge, Bartlett, Moat, and even the distant Sandwich and Ossipee ranges far to the south, loom blue and beautiful above them, while the valley of the Wildcat unrolls its slopes, checkered with farm and woodland, to where the river vanishes from sight around the turn at Jackson Falls. Fifty miles of sylvan beauty lie before you as you look down the narrow valley, over the green heights that rim it to the blue ones far beyond, and up again to the amethystine sky.

It is a wide world of sun and it is good to look at it now, for the path before you plunges to shade immediately and is to give you little more than a dapple of sunlight for five miles. Yet it is a wide and easy way for most of the distance, for which the chance traveller may thank the lumbermen, whose road it follows, and the Appalachian Mountain Club. The lumbermen opened it. The Appalachians have kept it up since the tote road was abandoned. They even have mowed its grassy stretches each spring, lest some fair Appalachian pilgrim set her foot upon a garter snake, inadvertently and without malice, and henceforward abjure mountaineering. A half-dozen brooks splash down the mountain-side and cross this trail, all for the slaking of your thirst, and if you do not find the garter snake to step on you may have a porcupine. Indeed, to judge from my own experience, the porcupine is the more likely footstool. Just before you round the low shoulder of Wildcat Mountain to enter the Notch is a burnt region full of gaunt dead trees, and this neighborhood grows porcupines in quantity, also in bulk. One of them looms as big as a bear at the first glimpse of him in the trail ahead, and if he happens to start from almost beneath your foot as you step over a rock, giving that queer little half squeal, half grunt of his, you are momentarily sure that you have kicked up Ursus Major himself.

But though the porcupine may squeal and move for a few shambling steps with some degree of quickness, he is by no means afraid of you. He just moves off a few feet, turns his back, shakes out his quills till they all point true, then waits for you to rush at him and bite him from behind—waits with a wicked grin in his little eye as he leers over his shoulder at you. Then if nothing happens he shambles awkwardly away into the shadows of the forest. If something does happen it is the aggressor that shambles away with a mouthful of barbed, needle-pointed quills. But then, why should anyone bite a porcupine? They do not even look edible, and judging by the numbers of them that strayed casually out of the path round the shoulder of Wildcat that day nothing has eaten any of them for a long time, else there had not been so many. In this burnt district you get a glimpse of Carter Mountain on the other side of the notch you are about to enter and then you plunge again into deeper woods on the west side, under the cliffs of Wildcat, whose very frown is hidden from you by the high trees.

The cool, shadowy depths here will always be marked in my mind as the place of great gray toads. I saw several of these right by the path, six-inch long chaps, looking very wise and old and having more markings of white than I ever before saw on a toad, besides a white streak all the way down the backbone. The place is as beautiful as these bright-eyed, curious creatures, and as uncanny. Mossy boles of great trees rise through its gloom and through the perfumed air comes the cool drip of waters. Moss is deep, and over it and the rough, lichen-clad rocks grows the Linnæa, holding up its pink blooms, fairy pipes for the pukwudgies to smoke. Here out of high cliffs have fallen great rocks which lie about the patch in mighty confusion. Here are caves, little and big, that might shelter all the hedgehogs roaming the fire-swept mountain-side below, and as many bears. Yet neither porcupines nor bears appeared, or any other living things except the great white-mottled toads, that would not hop aside for my foot, but sat and gazed at me with the calm patience of woodland deities.

Then the path swung sharp down the hill through lesser trees that gave a glimpse of the high frown of Carter cliffs, swimming in the sky above, and then—I wonder if every pilgrim does not at this point laugh with pure joy and caper a bit on road-weary legs, for here in the gruesome depths of the great Notch, at the climax point of its wildness, is a little clear mountain lake where surely no lake could be, set in thousand-ton fragments of mighty broken ledges. To look north is to see a little barrier of wooded ridge stretching across from side to side of the place, and between the eye and this a low barrier of wood growth among great rocks, behind which is the air of empty space. I pushed through this, expecting a crater, and behold! Here is another little round lake with lily pads floating on its surface, and beyond this an open space in the woods and the A. M. C. camp.

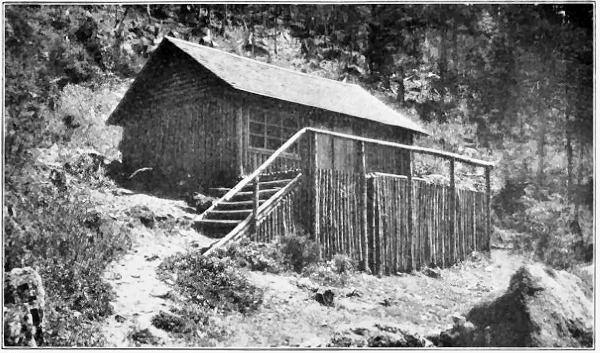

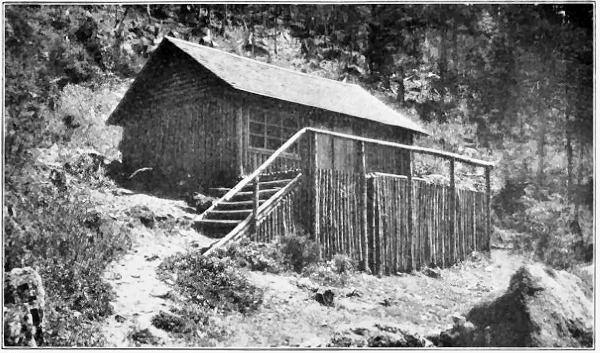

The Appalachian Mountain Club camp in Carter Notch

The time was early afternoon of one of the longest days of the year, and the sun sent a cloudburst of gold a thousand feet down the perpendicular cliffs of Wildcat Mountain and flooded the highest source of Wildcat River with it. The north wind poured its wine over the ridge and set the surface of the little lake to dancing with silver lights such as had greeted me in the river far below, in the boulders along the way, and in the spangles of the thousands of fritillary wings that had fluttered and folded as I passed. Here is the crucible for the making of these fairy gems, and I dare say the wise old toads from the shadows on the side of Wildcat just above are the sorcerers whence the tinkering trolls learned the trick of their manufacture.

I had to wait but a little while, however, to know the difference. Stretched on the slope on the farther shore of the flashing lake, I watched the sun swing in behind the high pinnacle of a wildcat cliff that leaps from the water's edge almost a thousand feet in air, its sheer sides embroidered by the green of young birch leaves. I had left the full tide of early summer in the Jackson meadows. Here it was early spring. There the strawberries were over ripe, here the blossoms were but opening their white petals, and the mountain moosewood and mountain ash, there long gone to seed, were here just in the height of bloom. By the lake side the Labrador tea offers its felt-slipper leaves for the refreshment of weary travellers who may thus drink from fairy shoon; nor need one go to the trouble of steeping, for the round heads of delicate white bloom send forth a styptic, aromatic fragrance that is as tonic as the air on which it floats. A drone of wild bees was in this air, and looking up the cliff toward the sun a million wings of tiny, fluttering insects made a glittering mist.

But even then the shadow of the pinnacle of the great cliff fell on the western margin of the pool and, as I lay and watched it, moved majestically out across the waters. It wiped the golden glow and the fluttering sheen of insects from the air, the glitter from the surface of the lake, and spread a cool mystery of twilight over all things which it touched. A chill walked the waters from the base of the cliff, whose rough rock brows frowned where the birches but an hour before had smiled, and all the hobgoblins of the wild Notch showed themselves in the advancing shadows. Rock sphinxes and dead-tree dragons suddenly appeared, and as the afternoon advanced so did the shadows of Wildcat Mountain, sweeping across the narrow defile and bringing forth all its weird and sinister aspects.

The way to the light of day lies down the stream southerly. But there is no stream. The waters of the upper lake flow to the other one beneath a great jumble of broken ledges, and then go on to form the stream farther down under a titanic rock barrier of shattered cliff and interspersed caverns. Gnarled and dwarfed spruces climb all over this great barrier, and so may a man if he have patience and will step carefully on the arctic moss which clothes the rocks and gives roothold to the spruces, watchful lest it slip from under him and drop him into the caverns of unknown depth below. It is a region of wild beauty of desolation even with the sun on it, and after the shadow of Wildcat has climbed it, its rough loneliness has something almost sinister about it. Only when its topmost rock is surmounted and the valley below shows down the Notch, still bathed in sunshine and peaceful in its green beauty and its rim of blue mountains far beyond, may one forget the weird spell which the shadows have cast on him in the very heart of the chasm. Here is the scintillant world of the Wildcat River valley once more, still bathed in sunshine, though the shadows of the range to westward creep rapidly toward its centre. I had seen the heart of its beginnings at the moment when the toiling trolls were at their work. I had seen the weirder spirits cast their mantle over the place, and far down the Notch I could hear the little river calling me to come down to it again as I scrambled off this giant's causeway to the friendly leading of the path and went on down through the region of great gray toads to the slope of a thousand porcupines, and on to where the footpath way enters the road. The smile of sunshine had gone from the face of the valley and the night shadows of Wildcat and its spurs were drawn across it, but only for a little was it sombre. With the darkness came a million scintillations of firefly lights in all its grasses, and out of the clear blue of the sky above twinkled back the answering stars.