VII

UP TUCKERMAN'S RAVINE

Day and Night Along the Short Trail to Mount Washington Summit

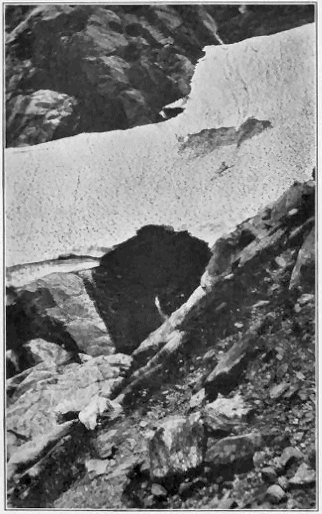

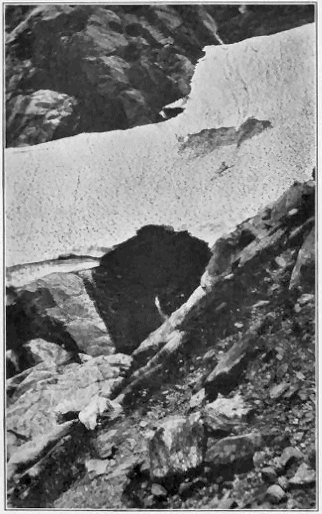

The snow arch at the head of Tuckerman's Ravine holds winter in its heart all summer long. In the sweltering heat of the early July weather it is an unborn glacier, a solid mass of compacted snow and ice, two hundred feet in vertical diameter and spreading fan-fashion across the whole head of the ravine. Out from under it rumbles a stream of ice water, and it still makes danger for the mountain climber on the upper part of the path which climbs the head wall of the ravine and goes on, up to the summit of Mount Washington. All winter long the north wind sweeps the snow over the round ridge between the summit cone and Boott's Spur and drifts it down the perpendicular face of rock which stands above the beginning of the ravine. There are summers when the heat of the sun, beating directly upon this glacial mass, melts it away. There are others when it lingers till the snows of autumn come to build upon it again.

"The snow arch at the head of Tuckerman's Ravine holds winter in its heart all summer long"

He who would do much mountain climbing in a comparatively short distance will do well to go up Mount Washington by the Tuckerman Ravine. A good motor road leads from Jackson to Gorham, and on, and the trail leaves this nine miles above Jackson. A. M. C. signs and the feet of thousands of mountain lovers have made the path's progress plain, but for a further sign the wilderness sends the swish of Cutler River, flashing over its boulders, to the ear all the way up to the snow arch, and it serves free ice water for the refreshment of travellers. Only in rare spots does this tiny torrent find time to make placid pools. All the rest of the way it leaps boulders, shelters trout in clear, bubbling depths, and makes its longest, maddest plunges at the cliffs down which foam the Crystal Cascades. Here, at the end of your first half-mile of ascent, you may lie in the shadow of maple and white birch on the brink of a narrow gulf, see the white joy of the river as it makes its swiftest plunge toward the sea, and listen to the myriad voices in which it tells the lore of the lonely ravine which the waters have traversed from the very summit of the head wall. No water comes down the Crystal Cascade that is not beaten into a foam as white as the quartz vein in which it has its very beginnings, high up the cone of the summit. It is as if this quartz were here turned to liquid life which spurts in a million joyous arches from the black rock which it touches and leaves more nimbly than the feet of fleeing mountain sheep. There are wonderfully beautiful pink flushes in this white quartz and you may see them as you go up the path to the summit above the alpine gardens of the plateau. But you do not have to climb that far to see them. The same colors of dawn are in the cascade when the sun filters through the leaves and touches those curves of beauty in which the river laughs down to its wedding with the Ellis in the heart of the Pinkham Notch.

In the heart of the snow arch is winter. On its steadily receding southern margin all through July is a continual dawn of spring. As the snow recedes the alders emerge bare and leafless. A rod down stream they are tinged green with the beginnings of crinkly leaves and have hung out their long staminate tassels of bloom. Another rod and they are in full leafage and the staminate tassels have given place to the brown seed cones. These mountain alders have a singularly crimped rich green leaf, and they so love the snow water torrents of Tuckerman's Ravine that they stand in them where they plunge in steepest gullies down the cliffs, bearing their tremendous buffeting with steadfast forgiveness. Sometimes the freshets skin them alive and leave them rooted with their white bones yearning down stream as if to follow the water that killed them. The torrents hurl rocks down and crush them, and always the downpour of water and mountain-side has bent them till in the steepest places they grow downward, their tips only struggling to bend toward the sky. Yet still in July they put out their bright green, corrugated leaves, array themselves in the beauty of golden tassels flecked with dark brown, and scatter pollen gold on the waters that now prattle so lovingly by.

In places the river-side banks are white with stars of Houstonia and the lilac alpine violets nod from slender stems nearby. Down the high cliffs the mountain avens climbs and sets its golden blooms in the most inaccessible places, flowers from the low valleys and the alpine heights thus mingling and making the deep ravine sweet with fragrance and wild beauty. The rough cliffs loom upward to frowning heights on three sides, but on their dizziest gray pinnacles the fearless wild flowers root and garland their crags, clinging in crevices from summit to base. With equal courage the alders have climbed them till they can peer at the very summit of the high mountain across the wind-swept alpine garden.

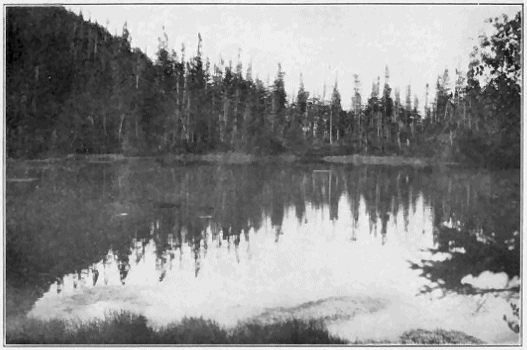

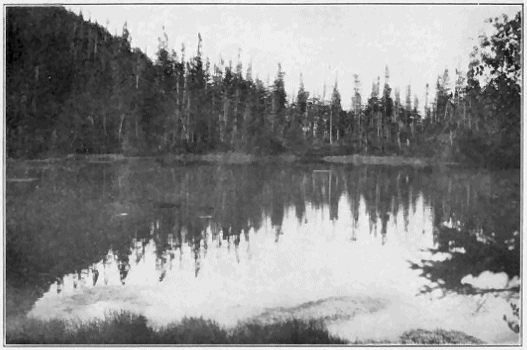

"Then the shadows are deep under the black growth that spires up all about the little placid sheet of water, though it still reflects the sapphire blue of the clear sky above"

By the middle of the afternoon the shadows of the heights begin to wipe the sunshine from the upper end of the ravine and the shade of the head wall marches grandly out, over the snow arch and on, down stream. The long twilight begins then and moves out to Hermit Lake by six. Then the shadows are deep under the black growth that spires up all about the little placid sheet of water, though it still reflects the sapphire blue of the clear sky above. The lake is, indeed, a hermit, dwelling always apart in its hollow among the spiring spruces, a tiny level of water, strangely beautiful for its placidity amid all the turmoil and grandeur about it. From its boggy margin the morning of the day that I reached it a big buck had drank and left his hoof prints plain in the mud among the short grasses. I waited long at evening for him to come back, but the only signs of life about the margins were the voices of three green frogs that cried "t-u-g-g-g" to one another by turns. One living long here might well measure the flight of time on a clear afternoon and evening by the changes of color in the lake. It is but a shallow pool, but you look through the mud of its bottom and see far below, by the inverted spires of the marginal trees, into infinite depths of a blue that is that of the sky but clarified and intensified by the clear waters from which it shines till it is to the eye as perfect and inspiring as a clear musical note that leaps out of silence to the longing ear.

As the day passes this color in the lake deepens and changes in rhythmical cadences till twilight brings a deep green, through which you see the inverted ravine below you more clearly than above. The one clear note has swelled into a symphony of color through which floats one entrancing tone, as sometimes lifts a clear soprano voice out of the fine harmony of the chorus, the pink of sunset fleece of clouds a mile above the head wall of the ravine. As the day fades, so does this high, clear tone, and the advancing night deepens the green to a black that is silence,—a silence that is velvety in body but scintillant with the glint of stars.

Through all this symphony of changing color a single hermit sang till the blackness of night welled up to the spruce top in which he sat, and as if to keep him company one or two wood warblers piped from the very darkness beneath where it seemed too dark for full songs, and they sang fragments only, too brief for me to identify the singers. From the lake itself came the voices of the three green frogs, speaking prophetically through the night with the single, authoritative words of true prophets. Just for a moment at dusk, from the icy waters of the stream above the lake, came a guttural chorus which I took to be that of tree frogs, which croak in the woodland pools of Massachusetts in March.

In the clear waters that run from the perpetual winter of the snow arch I had seen two of these frogs, of the regulation wood frog size and shape but wonderfully changed in color. Instead of the usual brown, here were frogs that were cream white throughout save for a black patch from the muzzle across either eye extending in a faint line down the side nearly to the hind leg. They seemed like spirit frogs with all the dross in their epidermis washed out by the solvent purity of that icy snow water in which they constantly dwell. In these same pools of the icy stream were caddice-fly larvæ which had woven armor for themselves with a warp of the usual spider-web threads and a filling of tiny stones. But their stones were the scales of mica with which the bottoms of the pools are paved, and as they slowly moved about they were sheathed in rainbows of sky reflections in these tiny surfaces. Such wonders of beauty has the heart of the high mountain for all that dwell in the depths of its ravines.

In the blackness of full night the song of the falling waters is the only sound that one hears in the ravine. This is an ever-varying multitone into which he who listens may read all the day sounds he has ever heard. The still air takes up the mingled voices of tiny cataracts and tosses them from one wall to another, and there are places along the path where this sound is that of a big locomotive engine with steam up, stopping at a station, the chu-chu of the air brakes coming to the ear with a definiteness that is startling. In other spots the echo of trampers' voices sound till one is sure that a belated party is on the trail and will arrive later to share the hospitality of the camp.

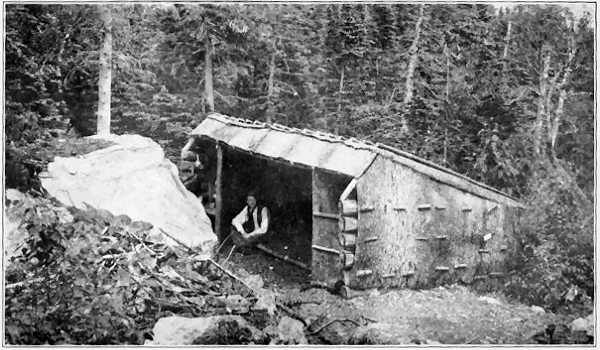

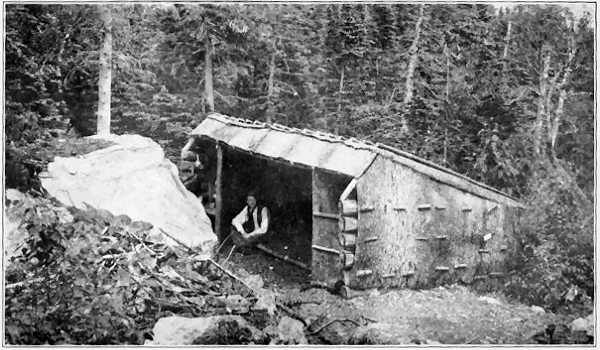

The Appalachian Mountain Club camp in Tuckerman's Ravine

Through it all rings the gentle lullaby of the wilderness, the drone of all the winds of a thousand years in the spruce tops and the crisp tinkle of clashing crystals when an ice storm has bowed the white birches till their limbs clash together in the xylophonic music of winter. All these and more are in the song which lulled me to slumber on the borders of Hermit Lake,—a slumber so deep and restful that I did not know when the porcupines came and ate thirteen holes in the rubber blanket in which I was wrapped to keep out the cold of the snow arch which creeps down the ravine behind the shadow of the head wall. Thirteen is an unlucky number when it represents holes in one's blanket, and the chill of interstellar space wells deep in Tuckerman's Ravine toward morning of a night in early July.

Twilight begins again by three o'clock. One may well wonder what time the hermit thrush has to sleep, he sings so long into the night and begins again before the dawn is much more than a dream of good to come. As the light grows the castellated ridge of Boott's Spur shows fantastic shapes against the sky, and the pinnacle of the Lion's Head which looms so high above Hermit Lake glooms sternly with grotesque rock faces which are carved like gargoyles along its ravineward margin. Beauty wreathes the cliffs in this wildest of spots, but goblins grow in the rock itself and peer from the wreaths to make their friendliness more complete by gruesome contrast. One wakes shivering and longs for the sun of midsummer to come out of the northeast over the slope of Mount Moriah and warm him. Far below in Pinkham Notch the night mists have collected in a white lake that heaves as if beneath its blanket slept the giant who carved the stairs over beyond Montalban Ridge. But the giant too is waiting for the sun, and though he stirs uneasily in his waking he does not toss off the blanket till it shines well over Carter Range and the day has fairly begun. The ravine gets the morning early at Hermit Lake. The widening slopes lie open to the light, but the Lion's Head jealously guards the snow arch and seems to withdraw its long shadow with reluctance. By and by the sun shines full upon the great white bank, and as at the pyramid of Memnon strikes music from it with the increasing tinkle of falling water.

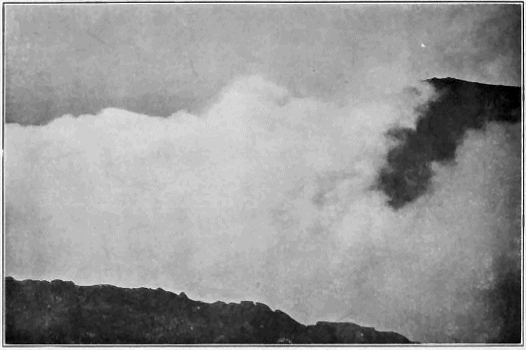

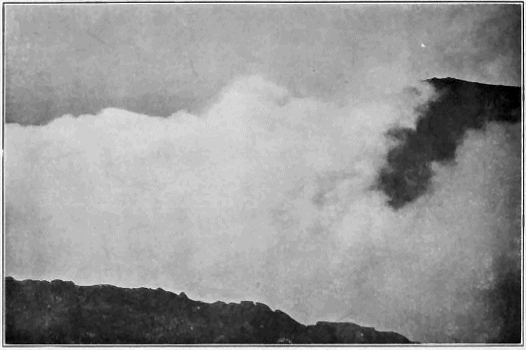

By this time the stirring of the giant's blanket has tossed off woolly fleeces from its upper side, and these climb toward the ravine in wraiths of diaphanous mist that now dance rapidly along the tree tops, now linger and shiver together as if fearful of the heights which they essay. These follow me as I toil laboriously up the almost perpendicular slope along the snow margin toward the head wall, and by the time I have worked around the dangerous glacial mass and surmounted the cliffs they are massed along the cold slope and seem to mingle with the snow into an opaque, nebulous mystery.

For a long time these do not get beyond the brow of the cliff. Now they bed down together, as dense and as full of rainbow colors under the sun as is mother-of-pearl, again little fluffs dare the climb toward the summit, fluttering with fear as they proceed and fainting into invisibility in the thin air that flows across the alpine garden. Tiny streams from the base of the high cone slip down the rocks to them and whisper in soft voices that they need have no fear, but whether it is fright or the compelling power of the sun that now shouts mid morning warmth over Carter Notch, these thin pioneers hesitate and vanish as the main body sweeps up from the Crystal Cascade and Glen Ellis Falls and fills all the lower ravines with that white blanket that began to stir at daybreak so far below. The giant is awake, has tossed his bed-clothes high in air, and is striding away along the Notch behind their shielding fluff.

I fancy him clumping up the Gulf of Slides and over to the ravines of Rocky Branch on his way to see if those stairs he built are still in order in spite of the disintegrating forces so steadily at work pulling the mountains down. Listening on the top wall of Tuckerman's I can hear these forces at work and do not wonder that he is uneasy. The steady flow of white water in a million tiny cascades is filing the rocks away all day long. But the water does far more than this. It seeps down into the cracks in the great cliffs, swells there with the winter freezing, and presses the walls apart.

"The giant is awake, has tossed his bed-clothes high in air, and is striding away along the notch behind their shielding fluff"

It dissolves and excavates beneath hanging rocks and cunningly undermines them till gravity pulls them from their perch and sends them down to swell the great masses of débris all along the bottoms of the ravine sides. Sitting on the head wall I hear one of them go every few minutes. Often it is only the click and patter of a pebble obeying that ever present force as it bounds from ledge to ledge down the wall. But sometimes a larger fragment leaps out at the mysterious command and crashes down, splintering itself or what it strikes on the way to the bottom. My own climbing feet dislodged many that have caught on other fragments, and in the steeper, more crumbled portions of the path each climber does his share in producing miniature slides. Except on rare occasions the fall of the mountains is slight, but it is continually going on wherever peaks rise and cliffs overhang.

Not till the mists out of the Great Gulf over on the other side of the mountain had swept around the base of the summit cone and hung trailing streamers down into Tuckerman's Ravine did the masses that filled it with white opacity to the top of the snow arch scale the head wall. Then they came grandly on and met and mingled with their kind till Boott's Spur disappeared and all the long ranges of mountains to southward were wiped out by an atmosphere that, with the sun lighting it, was like the nebulous luminosity out of which the world was originally made. Behind me they climbed the central cone, but slowly, almost, as I did. My trouble was the Jacob's ladder of astoundingly piled rocks of which the way is made. Theirs was a little cool wind that came down from the very summit and which steadily checked them, though they boiled and danced with bewildering turbulence against it. They wiped out the solid mountain behind me as I went till the cone and I seemed to be floating on a quivering cloud through the extreme limits of space.

Climbing this Tuckerman's Ravine path one gets no hint of the buildings on the summit. With the clouds below me and the rocks above I was isolated in space on a cone of jagged rock whose base was continually removed from beneath me as I climbed. It seemed as if, when I did reach that high pinnacle, the last rock might fade from beneath my feet and leave me floating in the white void that came so majestically on behind me. We reached the top together, but the crisis was not so lonely as I had imagined. Instead, I found myself walled in by opaque mists indeed, but still with much solid rock beneath my feet and a friendly little village, a railroad track and station, a stage office and stables, and an inn at hand, all with familiar human greetings for the weary traveller. You may come to the summit by many paths, by train, carriage or motor, but no trail has more of beauty, or indeed more of weirdness if the fluff of the giant's blanket follows you to the summit, than the three miles and a half of steady climbing by way of Tuckerman's Ravine.