X

MOUNTAIN PASTURES

Their Changing Beauty from Low Slopes to Presidential Plateaus

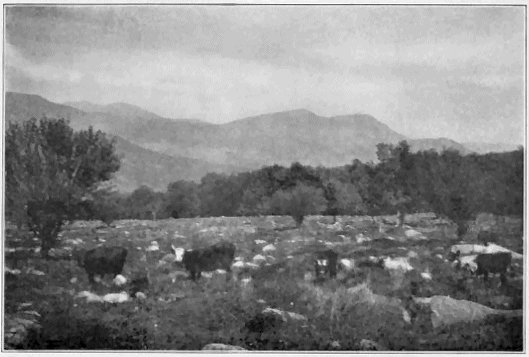

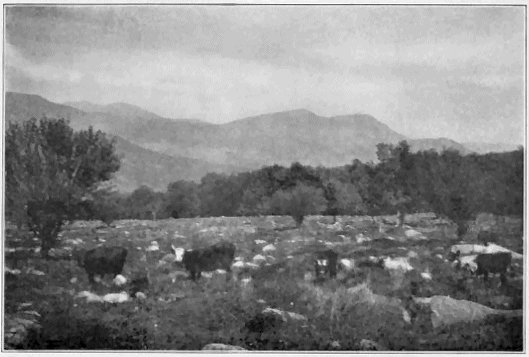

On the mountain farms the cultivated fields hold such levels as the farmer is able to find. Often on the roughest mountain side he has found them, treads on the stairways of the hills whose risers may be perpendicular cliffs or slide-threatening declivities. These last are for woodland in the farm scheme, if tremendously rough, or if they have roothold for grass and foothold for cattle they are pastures. Thus it is the pastures rather than the cultivated lands that aspire, and from their heights one looks down upon the farm-house and the farmer and his men at work in the hay fields. The stocky, square-headed, white-faced cattle may well feel themselves superior to these beings far below who groom and feed them, and from their wind-swept ridges I dare say they have the Emersonian thought, even if they have never learned the couplet:

"Little recks yon lowland clown

Of me on the hilltop looking down.”

"The stocky, square-headed, white-faced cattle may well feel themselves superior to these beings far below who groom and feed them"

These mountain cattle are of many breeds, according to the fancy or the fortune of their owner. Probably many of them are mongrels whose ancestors it would be hard to determine, yet there seems to be a strong resemblance in some to those cattle one sees on Scottish hills and in the highlands of the English border, and one wonders if here are not lineal descendants of the stock which came in with the early English settlers. At least the white-faced ones have been settled on the mountain pastures long enough to become part and parcel of them. Except when in motion they so fit their rocky surroundings as to be with difficulty picked out from them by the eye. One might say the pasture holds so many hundred rocks and cattle, but which is which it takes a nice discernment to decide. Especially is this true when the herd stands motionless and regards the wandering stranger. Then the red bodies are the very color shadows of the green pasture shrubs and the white faces patches of weather-worn granite. Sometimes it is disconcerting to tramp up to such a rock in such a shadow and have it suddenly spring to its feet with an indignant "ba-a" and flee to the forest with much clangor of a musical bell.

Most of the mountain cattle wear this bell, which is but a hollow, truncated, four-sided pyramid with a clapper hung within. It does not tintinnabulate, but "tonks" with a tone that is low, but carries far and seems always a part of the woodland whence it so often sounds,—woodland in which pasture and cattle so continually merge. In its mellow tones the clock of the pasture strikes, marking the lazy hours for the loving listener. In the time when the slender thread of the old moon disputes with the new dawn the honor of lighting the high eastern ridges, I hear it chorusing in mellow merriment as the herd winds up the lane from the big old barn. It briskly rings the changes of the forenoon as the herd crops eagerly among the rocks, the slowing of its tempo marking the appeasing of hunger. Through the long, torrid hours of mid-day it sleeps in the deep shadow of the wood, toning only occasionally as the drowsy bearer moves. Then with the coming of the afternoon hunger I hear it again, moving down the mountain with the day, to meet the twilight and the farmer at the pasture bars.

As these mountain cattle are curiously different in aspect and carriage from those of our lowland pastures in eastern Massachusetts, so the pastures themselves differ widely in more than location and level. Here in part is the old world of bird and beast, herb, shrub and tree, yet many an old friend is missing and many a new one is to be made. It is difficult to believe that a pasture can be fascinating and lovable without either red cedars or barberry bushes, yet here are neither, and though the slim young spruces stand as prim and erect as the red cedars of a hundred and fifty miles farther south, they do not quite take their places, nor do they have the vivid personality of those trees. It is the same with the barberry. There is an individuality, an aura of personality about the shrub that forbids any other to take its place or indeed to in any way resemble it. The mountain pastures are the worse for that.

For my part I miss the clethra more even than these. July is the time for those misty white racemes to be coming into bloom and sending down the wind that spicy, delectable fragrance that seems to tempt him who breathes it to adventure forth in search of all woodland romance. But the clethra is a lover of the sea rather than the mountains and it has never voyaged far up stream. The waters of the mountain brooks have lost their clearness long before they greet the clethra on their banks. The striped moosewood and the mountain moosewood, both pasture-bordering shrubs of the high pastures, are beautiful in their way, but they cannot make up for this sweet-scented, brook-loving beauty of the lowlands.

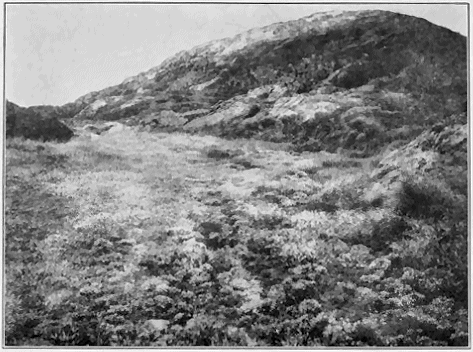

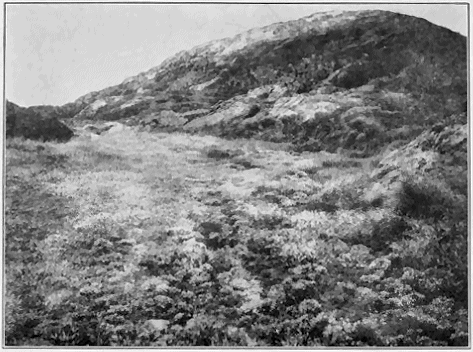

There are two pasture people, however, who love the high slopes of the White Mountain pastures as well as they do the sandy borders of the Massachusetts salt marshes. These are the spiræas, latifolia and tomentosa. The latter, the good old steeple bush or hardhack, moves into some rocky, open slopes till it seems as if there was hardly room for any other shrub or scarcely for grass to grow, and makes the whole hillside rosy with its pink spires. It always seems to me as if the hardhack should be hardier than its less sturdy-looking, more dainty sister, the Spiræa latifolia or meadow-sweet. In most pastures of the foothills, so to speak, I find them together, but as one goes on up the slopes of the high ranges the hardhack vanishes from the wayside leaving the meadow-sweet to climb Mount Washington itself and show the delicate pink of its bloom over the head wall of the Tuckerman Ravine and about the Lakes of the Clouds. Nor has it altogether escaped the pasture there. The white-faced cattle remain behind with the hardhack, but the deer come over the col from Oakes Gulf and browse on its leaves and those of the Labrador tea and drink from the clear waters of the high lakes. These herds of the highest pastures bear no bell and fit into the color scheme of the landscape better even than the white-faced cattle, and it is no wonder that they escape observation. Yet I find their hoof marks at almost every drinking place of these highest mountain moors.

In these last days of July the most conspicuous bird of the pastures is the indigo bunting. I say this advisedly and in the presence of goldfinches, myrtle and magnolia warblers, purple finches and various sparrows, including the white-throat, also some other birds who breed and sing there. Yet of all these the indigo bunting seems by numbers and pervasiveness to be most in the public eye; I being the public. Early in the morning he sings. In the full warmth of noontide he sings, and I hear him when the sun is low behind the Presidential Range and the clouds are putting their gray nightcap on the summit of Washington. Always it is the same song, which slight variations only tend to emphasize without obscuring. "Dear, dear," he says, "Who-is-it, who-is-it, who-is-it? dear, dear, dear." And sometimes he adds a little whimsical, stuttering, "What-do-you-know-about-that?" He sits as he sings on the penultimate twig of some pasture shrub or tree, and as the sun shines on his indigo blue suit it flashes little coppery reflections from it that might well make one think him the product of some skilled jeweller's art rather than born of an egg in the bushes.

With the self-consciousness of the average summer visitor, I at first thought that this song of his referred to me. I fancied that he was calling to his little brown wife at the nest in the nearby bushes, exclaiming about this stranger who was tramping the pastures and asking her about him. If you wish to know about new people in town ask your wife. Any happily married indigo bunting will give you that advice. But I know his theme better now. I have seen the wife slip slyly out of the dense green of the thicket, and have most impolitely invaded it, there to find the compact grass nest full of a new-born bunting family. I know now that the father bunting sits in the tree tip and exclaims all day long over the arrival of these. Seeing their huddled, naked forms, their astounding mouths and unopened eyes, I do not wonder that he exclaims in perplexity and indeed some dismay over the new arrivals. "Dear, dear," he says, "Who-is-it, who-is-it? What-do-you-know-about-that?" He will never get over his astonishment at such tiny gorgons coming from those pale, pretty eggs that were there but a few days ago. Nor do I blame him one bit. It does not seem possible that these miracles of ugliness can ever grow up to be such sleek, beautiful birds as this father of theirs that sits on the treetop and all day long fills the pasture with echoes of his song of wonder over them. No. His song had no reference to me, but was strictly concerned with his own affairs. Like the other native-born mountaineers, he does not take the summer visitors any too seriously. It is interesting to go up the mountains from one pasture, scramble to another and see what lowland folk fall behind and how the habits of those that keep up the climb change as they progress into the higher altitudes. The woodchuck is not missing here, but he is not the same. He is the northern woodchuck, very like his Massachusetts cousin in habits but grayer, leaner and rangier. At this time of year a Massachusetts woodchuck is so fat that if you meet him he fairly rolls to his hole. The northern woodchuck gets into his with a scrambling bound that shows much less accumulation of adipose tissue. I fancy this leanness and greater alertness is due to the greater numbers and greater alertness of his woodland enemies. The pastures are full of foxes, and when they get hungry they go down and dig out a woodchuck for dinner. But even the northern woodchuck fails the pastures in their higher portions.

One by one the lowland flowers fall back and the lowland trees and shrubs, also, until high on the Presidential Range the pastures themselves, in the common use of the word, have failed as well. Yet I like to think the true use of the word includes that debateable land at the tree limit as pasture land. In the economy of a farm it would surely be of use for nothing else, and it would make excellent pasturage in summer, were there farms near enough to use it. It always seems homelike, this region of grass and browse, coming to it as one does from the dark depths of fir woods and dwarfed deciduous trees. The hemlocks, beeches, yellow birches and maples have stayed behind in the region of cow pastures. Here where sometimes the deer come and where mountain sheep ought to find pasturage, only the hardiest of pasture people have dared to take their stand. The firs and spruces have come up, growing stockier and more gnome-like at every hundred-foot rise, until above the head walls of the ravines they shrink to low-growing shrubs not knee high, except where they have cunningly taken advantage of some hollow. Even there they rise no higher than the shelter that fends them from the north wind. Above that they are trimmed down, often into grotesque shapes like those that old-time gardeners affected, shearing evergreens into strange caricatures of beasts or men. Often on these Alpine pastures you find a boulder behind which on the south a fir has taken refuge. Close up to the rock it mats, drifting away from it, southerly, in much the same lines that a snowdrift would assume in the same position. There is in this nothing of the spiring shape of the same variety of spruce or fir in the valley pastures far below. Yet the botanists accept this as an individual distortion due to environment and do not class these firs or spruces of the mountain pastures as a variety different from those that grow below.

Mountain Sandwort in bloom on a little lawn near Mount Pleasant on the last day in July

They think otherwise of other trees.

The white birches come up in location and come down in size on these mountain pastures very much as do the spruces and firs. We have the big canoe birch of the lower slopes, often a splendid tree that matches any in the forest in height. On higher ranges it shrinks and even undergoes certain structural changes that have given excuse for the naming of new varieties. Hence, beginning with Betula papyrifera in the valleys we have a shrinkage to cordifolia, minor, and glandulosa with its sub-variety rotundifolia, this last a veritable creeping birch which sticks its branches but a little above the tundra moss in places where the spruce and fir trees are not much different in character and the willow becomes most truly an underground shrub with no bit of twig showing above the surface and only the little round leaves cropping out, making a growth that is more like that of a moss than that of a tree. To such straits do wind and cold reduce the trees that defy them.

Yet in spite of the botanical classification which sets up these dwarfed trees as different varieties from those of the lower slopes, one cannot help wondering if the differentiation is justified. Suppose the seeds of a big paper birch from the lower valley were planted among the creeping willows of the Alpine Garden on Mount Washington. Would they not grow a dwarfed and semi-creeping Betula glandulosa or rotundifolia? Would not the seeds of glandulosa, if blown down into the lower valley and growing in the soil among the paper birches produce Betula papyrifera? It always seems to me that there is less difference between the creeping birches of the high plateaus of the Presidential Range and the paper birches of the lower slopes than there is between the grotesquely dwarfed firs and spruces of the Alpine Garden, and the big ones that grow in Pinkham Notch and in the rich bottom lands of the lower part of the Great Gulf.

The alders of these highest pastures are very dwarf, and because of the puckered leaf margins have received the specific name of crispa, being familiarly known as the mountain alder or green alder. Yet we have in lower pastures the downy green alder, Alnus mollis, so much like its higher-growing relative that even the authorities say it may be but a variation. Here again one wonders if the difference is not that of climate on the individual rather than one of species, and if the seeds of Alnus mollis from the banks of the Ellis River if planted along the head wall of the Tuckerman Ravine would not grow up to be Alnus crispa. It seems as if there was a very good opportunity for experimentation along some line between the Silver Cascades and the rough rocks at the base of the summit cone of Washington. Down in the valleys the juncos build their nests in low shrubbery or at least on the top of the ground. Up on the side of the summit juncos build actually in holes in the ground, and lay their eggs almost a month later than those below. Here is a variation in habit, yet in each case the bird is Junco hiemalis; perhaps when the scientists really get around to it we shall have the cone builders classed as variety hole-iferus.

But however we may differ as to the naming of the plants and birds that frequent them, all who have climbed that far confess to the beauty of these highest pastures of the New England world. To wander in them of a sunny summer day for even a short time is to begin to be fond of them, an affection which increases with each subsequent visit. There soon gets to be a homey feeling about them that lasts at least while the sunshine endures. With the passing of the sun comes a difference. The chill of the high spaces of the air comes down then and the winds complain about the cliffs below and above and prophecy disaster to him who remains too long. It is well then to scramble downward and leave the highest pasture lands to the deer, if they choose to climb out of the sheltering black growth below, or to such spirits of lonely space as may come at nightfall. Far below are the man-made pastures that are friendly even at nightfall, and it is good to seek these. The tonk of the cow-bells will lead you in lengthening shadows out of the afterglow on the heights down into the trodden paths and beyond to the pasture bars.