IX

MOUNT WASHINGTON BUTTERFLIES

Filmy Beauties to be Found in Fair Weather on the Very Summit

The height of the butterfly season comes to the rich meadows about the base of Mount Washington in mid-July. The white clover sends its fragrance from the roadside and the red clover from the deep grass for them, and all the meadow and woodland flowers of midsummer rush into bloom for their enjoyment, while those of an earlier season seem to linger and strive not to be outdone. The cool winds from the high summits of the Presidential Range help them in this, and even in the summer drought the snow-water from the cliffs and the night fogs of the ravines keep them moist and fresh. No wonder that butterflies swarm in these meadows and even climb toward the summits along the flowery paths laid out for them up the beds of dwindling mountain torrents and under the cool shadows of forests impenetrable to the sun. Butterflies come to know woodland paths as well as man does and delight to follow them.

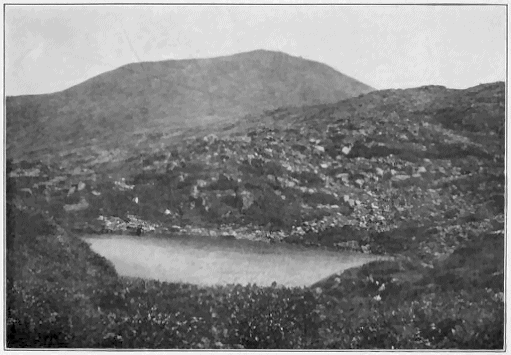

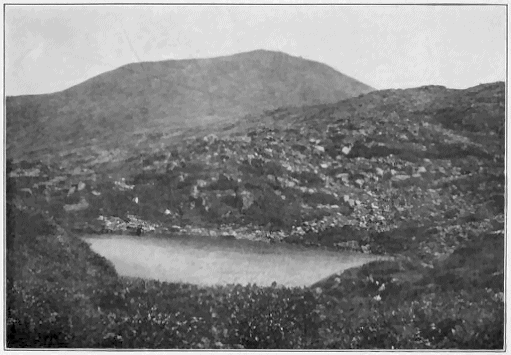

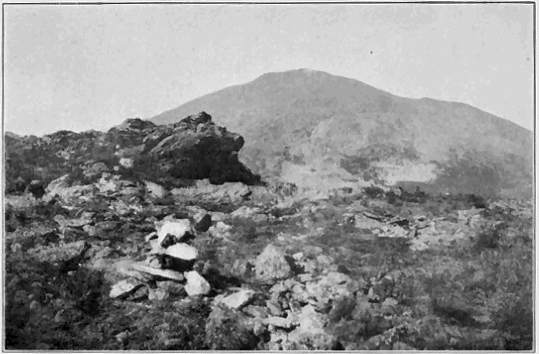

Butterfly-time on Mount Washington, the summit seen over the larger of the Lakes of the Clouds

Of a July day the butterflies and I journeyed together up the flower-margined carriage road that leads to the summit of Mount Washington. They may have been surprised at the pervasiveness of my presence. I am sure I was at theirs, which lasted as long as the marginal beds of wild flowers did.

To climb this smooth road leisurely, on foot, is always to marvel at the engineering skill which found so steadily easy a grade up such an acclivity and so cunningly constructed it that it has been possible to keep it in good condition all these years—it was finished in 1869—in spite of summer cloudbursts and the gruelling torrents of melting snow in early spring. One is well past the first mile post before he realizes that he is going up much of a hill. The rise is that of an easy country road and might be anywhere in the northern half of New England from all outside appearances.

The striped moosewood and the mountain moosewood growing by the roadside under white and yellow birch and rock maple suggest the latitude. The white admiral butterflies emphasize the suggestion. Rarely have I found these plants or this insect south of the northern boundary of Massachusetts. The white admirals flip their blue-black wings with the broad white epaulettes up and down the road in numbers. Butterflies of the shady spots, they find this highway where the trees arch in and often meet above peculiarly to their taste. Yet the meadow-loving fritillaries outnumber the admirals ten to one. Not even among the richly scented clover of the flats below, not even in the full roadside sun on the milkweed blooms which all butterflies so love, are they so plentiful. I suspect them of having a strain of adventurous blood in their veins, such as gets into us all when among the mountains and sets us to climbing them, and later observations bear out the suspicion. It was a day to lure butterflies to climb heights, still, steeped in fervid sun heat, and redolent of the perfect bloom of a hundred varieties of flowering plants.

At first I thought these all specimens of the great spangled fritillary, Argynnis cybele, but they gave me such friendly opportunities for close examination that I soon knew better. The greater number of these mountain climbing butterflies were a rather smaller variety with a distinct black border along the wings, Argynnis atlantis, the mountain fritillary. They swarmed along the narrow shady road as plentiful as the blossoms of field daisies and blue brunella. With playful necromancy they made the daisies change kaleidoscopically from gold and white to gold and black, or they folded their wings and set the flower stalks scintillant with silver moon spangles. So with the blue brunella blooms. They flashed from close spikes of modest blue flecks to great four-petalled flowers of gold and silver and black, a blossom that would make the fortune of any gardener that could grow it, and presto! the miracle of bloom rose lightly into the air on fluttering wings and the stalk held only the shy blue of the brunella after all. Such is the magic of the first mile of the ascent, which might be any easy rise under the deciduous shade of most any little New Hampshire hill, so far as appearances go.

During the second mile spruces slip casually into the roadside. They do it so unassumingly that you hardly know when, they and the firs. But the swarms of butterflies go on up the grade and through the dense foliage you still glimpse no mountain tops. With them shines occasionally the pale yellow of Colias philodice, and little orange skippers skip madly from bloom to bloom of the wayside flowers that still fill the margins from woods to wheel tracks. Clearwing moths buzz and poise like miniature humming birds, and with them in the deeper shadow flits a small white moth so delicately transparent and so ethereally pure in color that when he lights on a leaf the green of it shines through his wings.

These first two miles of the carriage road are amid scenes of such sylvan innocence that a partridge with her half-grown brood hardly feared me as their path crossed mine, and they flew only when I approached very near them. Cotton-tailed rabbits hopped leisurely across in front of me, in no wise excited by my approach, and though the chipmunks whistled shrilly and dived into their holes before I touched them, they waited almost long enough for me to do it. The roadside flowers climbed bravely up the second mile among the wayside grasses, white clover, blue-eyed grass and golden ragwort, with the daisies, these not so plentiful as below, and the gentle brunella, and out of the woods came as if to meet and fraternize with them the rose-veined wood sorrel, its pure white petals seeming even more diaphanous because of the rose-veining. The heart-shaped, trifoliate leaves of this lovely little plant which climbs the great mountain on all sides are not those of the veritable shamrock, perhaps, but they are enough like them to prove to a willing mind that St. Patrick must surely have climbed Mount Washington in his day, and that this gentle insignia of his clan remained behind to prove it. It is a flower of shaded mossy banks in deep evergreen woods, where its tender white flowers, with their beautifully rose-shaded, translucent petals, delight the eye along the lower and middle reaches of all paths that lead to the summit.

Toward the end of the second mile one realizes that he is climbing high. Through the trees to westward flit glimpses of the deep valley of the Peabody River, when he has risen, and beyond it the misty blue wall of the Carter Range, rising ever higher behind him as he goes up. The fritillaries come on, but the admirals drop behind to be seen no more, their places taken by an occasional angle-wing, Grapta interrogationis or Grapta comma. As the road rises the wayside flowers too fall behind, leaving lonely places, though well up to the Halfway House, nearly four miles up, white and pink yarrow is to be found, flanked by bunchberry blooms and the lovely greenish yellow of the Clintonia. This has half-ripened berries in the lowlands at the base, but toward the summit of the mountain it blooms till well into the middle of July, perhaps later. The butterflies fall behind as the roadside flowers do, yet now and then a mountain fritillary goes by and almost at the Halfway House I saw the most superb Compton tortoise, Vanessa j-album, that I have met anywhere. Below the Halfway House young spruces have crowded into the roadside to the very wheel tracks, and the last of the lowland blooms has vanished. On the day that I came looking for them the lowland butterflies had vanished too, and the road seemed bare and desolate for two or three miles, indeed until the alpine plants of the high plateau began to appear, and with them the Arctic butterfly that makes this summit home, the curious little Oeneis semidea.

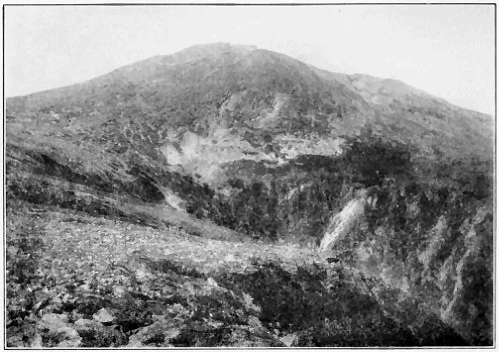

I had thought to find this, "the White Mountain butterfly," the only variety of the plateau and the summit cone, but in this the day and the place had more than one surprise in store for me. There are many days in summer when even the hardiest, strongest-flying lowland butterfly would not be able to scale the summit because of wind and cold, but this day had only a gentle air drifting in from the north, and the heat, which was a killing one below, was there tempered to that of a fine June day. The sudden bloom of the alpine plants had passed its meridian, but many were still in good flower. All along on the head wall of the Tuckerman Ravine and out upon the Alpine Garden were the pink, laurel-like cups of the Lapland azalea. There was the Phyllodoce cærulea with its urn-shaped corolla turning blue as it withers, the three-toothed cinquefoil, Potentilla tridentata which looks to the careless glance like a little running blackberry vine with its star of white bloom, and everywhere low clumps of the lovely little mountain sandwort, Arenaria grœnlandica, the only petal-bearing plant that dares the very summit, where its white, cup-shaped blooms make the bleak rocks glad.

On the Alpine Garden and at the ravine heads are lower level flowers which come up and mingle with these. The buttercup-like blossoms of the mountain avens flash their rich yellow. The Labrador tea puts out its white umbels and sends spicy fragrance down the wind. The houstonia grows bravely its little white, four-pointed stars with their yellowish centre, and cornel and even Trientalis, the American star-flower, grow from the tundra moss and make a brave show in that bleak spot. Boldest of all is the great, rank-growing Indian poke, with its erect stem of big green leaves and its topping spike of greenish bloom. High up to the angles of the rock jumble of the cone, wherever the water comes down into the Alpine Garden, this climbs with a bold assurance that no other lowland plant equals. It is plentiful in the neighborhood of the Lakes of the Clouds and high on the head wall of the Tuckerman Ravine it sprouts under the receding snow, blanched like celery.

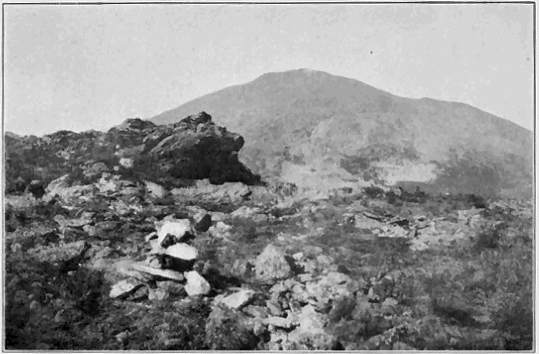

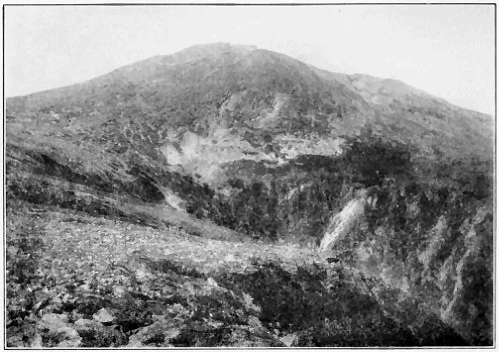

The fantastic lion's head which, carved in stone, guards the trail along Boott's Spur toward the summit cone of Washington

All these and more were in bloom on the plateau that supports the high cone of Washington summit on that day, and up to them had come the lowland butterflies. Most plentiful were the mountain fritillaries, but often a great spangled fritillary spread his wider wing above the head wall of Huntington or Tuckerman and soared along the levels. With these was an occasional angle-wing, Grapta interrogationis and Grapta progne, feeding in the larval stage on the leaves of the prickly wild gooseberry which is common well up to the base of the summit cone. Strange to relate, the beautiful, hardy, and common mourning cloak was not to be seen on the days in which I hunted butterflies about the summit, but his near relative, the Compton tortoise, Vanessa j-album, was there, and the smaller but lovely little Vanessa milberti, with his wings so beautifully gold-banded, I saw frequently. Milbertis flew up out of the Great Gulf toward the summit, and one afternoon I found one of them carefully following the Crawford trail down, winding its every turn a foot above the surface as if he knew that it was made to show the way. To the very summit, circling the Tip Top House, came big, red-winged, black-veined monarchs, and all the varieties I had seen in the Alpine Garden came up there too, most numerous of all being the mountain fritillaries. I take it that no one of these lowland butterflies is bred at these high levels, but that all wander up when the sun is bright and the wind still enough to permit the excursion.

"Semidea persistently haunts the great gray rock-pile which is the summit cone"

Most interesting of all to the lepidopterist is the one Arctic butterfly of our New England fauna, Oeneis semidea, "The White Mountain Butterfly," which might be perhaps better called in common parlance "The Mount Washington Butterfly," as it is commonly believed to be restricted in its habitat, so far as New England is concerned, to the high summit cone of Mount Washington. Holland so states in his excellent butterfly book. As a matter of fact the insect is plentiful over a rather wider range. I found it along the Crawford trail out to the Lakes of the Clouds and Mount Monroe, as well as along the lawns and Alpine Garden and down the carriage road far below the summit cone. It is also found at similar altitudes on Jefferson, Adams and Madison, its habitat being rather the high peaks of the Presidential Range than Mount Washington alone.

But semidea persistently haunts the great gray rock pile which is the summit cone. Wherever you climb, there it flutters from underfoot like a two-inch fleck of gray-brown lichen that has suddenly become a spirit. Alighting, it turns into the lichen again. In rough weather the other butterflies go down hill into the shelter of the ravines, but this one has learned to fight gales and midsummer snow storms and hold patriotically to its native country. Even in still weather when disturbed it skims the surface of the rock in flight, seeming to half crawl, half fly, lest a gale catch it and whirl it beyond its beloved peak. Its refuge is the little caverns among and beneath the angled boulders, and when close pressed by a would-be captor it flies or climbs down into these as a chipmunk would, and remains there till the danger has passed. It seems to be born of the rocks and to flee to its mother as children do when afraid of anything. It is our hardiest mountaineer. Neither beast nor bird dares the winter on this high summit. Yet here, winter and summer, is the home of this boreal insect which in the egg or the chrysalid withstands cold that often goes to fifty below Fahrenheit, and is backed by gales that blow a hundred miles an hour. No wonder this little but mighty butterfly takes the colors of the rocks that are its refuge.

It is the only easily noticed form of animated wild life that one is sure to find on the very summit, even in summer. Hedgehogs sometimes come to the door of the Tip Top House in summer weather and have to be shooed away, and gray squirrels have been seen there; but these, like the tourists, are casual wanderers from the warmer regions below. I believe the only bird that makes its summer home on the cone is the junco, though I heard song-sparrows and white-throats sing down on the levels of the plateau, at the Alpine Garden and about the Lakes of the Clouds. The juncos breed about these next highest levels in considerable numbers, and one pair at least bred this summer high up on the summit cone, about a third of the way down from the top toward the Alpine Garden. Like the Arctic butterflies, the refuge of this pair was the interstices of the rocks themselves, the nest being actually a hole in the ground, beneath an overhanging jut of ledge where the moss from below crept perpendicularly up to it, but left a gap two inches wide into which the mother bird could squeeze. It was almost as much of a hole in the ground as that in which a bank swallow nests, absolutely concealed, and protected from wind or down-rush of torrential rain.

Rare butterflies are not the only insects which tempt the entomologist to the very summit of Mount Washington. On my butterfly day there I found two members of the Cambridge Entomological Society dancing eagerly about the trestle at the terminus of the Mount Washington Railway, collecting beetles, of which they had hundreds stowed away in their cyanide jars. I'll confess that all beetles look alike to me, but these grave and learned gentlemen were ready to dance with joy at their success of the afternoon before at the Lakes of the Clouds, where each had captured one Elaphrus olivaceus. The name sounds like something gigantic; as a matter of fact, olivaceus is a tiny, dark, oval-shaped beetle, on which these enthusiasts saw beautiful striæ and olive-yellow stripes. Having the eye of faith I saw them too, but only with that eye. Together we went hunting the Alpine Garden for Elaphrus lævigatus, another infinitesimal prodigy of great rarity and scientific interest, but the omens were bad and lævigatus escaped. Such are some of the magnets with which this mighty mountain top draws men and women from all over the world, to spend perhaps a day, perhaps a summer, among its clouds, its scintillant sunshine and its ozone-bearing breezes.

Storm winds drive most of us below. When they blow, all the beautiful lowland butterflies set their wings and volplane down to the shelter of the valleys behind the jutting crags and the head walls. The chill of descending night as well drives these light-winged creatures off the hurricane deck of this great rock ship of the high clouds. But the thousands of hardy Oeneis semidea simply fold their lichen gray wings and creep into miniature caverns of the jumbled granite, waiting, warm and secure, for the light of the next sunny day.