XII

THE LAKES OF THE CLOUDS

The Alpine Beauty of These Highest New England Lakes

At nightfall from the summit of Mount Washington the Lakes of the Clouds look like two close-set, glassy eyes in the face of a giant, a face that stares up at the sky far below and whose hooked nose is the summit of Mount Monroe. As the light passes, the glassy stare fades from these and they lie fathomless black orbs that gaze skyward a little while, then close, and the giant, whose outstretched body is the southern half of the Presidential Range, sleeps. In the full sunshine of a pleasant forenoon one knows them for tiny, shallow lakes, and so near do they look that it seems almost as if a good ball player might cast a stone into them from the rim of the summit just behind the Tip Top House. As a matter of fact, they are a little over two miles away over declivities and ridges that lie above the tree line. For the most part the trail to these lakes, whether one comes from Mount Washington or along the Crawford bridle path, seems bare and desolate to the overlooking glance. But when one gets down to it he finds it full of beauty and interest. The southern part of the Presidential Range, between Mount Washington and Mount Clinton, is a mighty ridge, out of which topple the crests of Monroe, Franklin and Pleasant, a giant still by day, but now a giant wave petrified.

Coming up the land from the south I had thought that the lifting of Mount Washington through the plastic earth had caused the waves of land to radiate from it in all directions, but to stand on the highest summit is to see that this is not so. The force that made the mountains to the south and the mountains to the north is the same, and the Presidential Range is a result, also, and not a cause. It is but the seventh wave of those which ride in from the northwest, and the force which made them all came over the land from countless leagues beyond. The Presidential Range lifts out of the hollow of the wave, which is the Ammonoosuc Valley, in a long clean sweep southeastward, exactly as a mighty wave does at sea. It pinnacles into the various peaks and it drops suddenly, almost sheer in places, into the next hollow beyond. This hollow beyond the northern peaks is the Great Gulf, beyond the southern peaks is Oakes Gulf, and beyond Mount Washington itself begins with Huntington and Tuckerman ravines. Something drove mighty waves through the land from the west, sent them pinnacling five and six thousand feet above the sea level, and froze them there. The main wave is the solid rock mass thirteen miles long and in the neighborhood of five thousand feet in height above the sea level. The crests are the summit cones, jumbled piles of great mica-schist rocks, varying in size from a cook-stove to a city block, all seeming to have been tossed together in a disorderly heap and to have settled down into such regularity as gravity at the moment allowed. The central cores of these may be solid. Certainly the outer part is but a jumble of loose rocks that sometimes topple and grind down over one another at a touch and that give air and water access to unknown depths.

Hence on the peak of Washington, for instance, or Adams, or Jefferson, one may see the somewhat astonishing spectacle during a heavy downpour of rain of a great rock pinnacle absorbing the water as fast as it falls. One would expect miniature cataracts and a rush of a thousand streams down such a summit at such a time. Yet the downpour gets hardly beyond the spatter of the drops. The loose rocks absorb and hide it. Hence after every rainfall welling springs on the summits, and farther down the gurgle of waters running in unseen crevices one never knows how far below the surface. Hence, also, lakes of the clouds. After every rain there are well-filled springs on the very top of Washington, and it is only after many days of dry weather that these begin to dwindle. There are chunks of ledge up there so hollowed out toward the sky that they hold the rain by the first intention, so to speak, and every cloud that touches them oozes from its fold more water for their sustenance. Often for weeks these pools reflect the stars by night and evaporate under the shine of the sun by day. In one of them in late June of this year I found a pair of water striders skipping merrily about on the calm surface. Two weeks of drought dried the pool up completely, and I thought these daring adventurers on the ultimate heights dead, and indeed wondered much how they came there at all. But later a good rain filled the pool again and my two water striders appeared on its surface once more, merry as grigs. I am divided in my mind as to what they did meanwhile. Perhaps they simply survived the drought by main strength; perhaps they followed the dew down into cracks between the rocks and there abided in at least some moisture till the rain came. But I am more of the opinion that they simply skipped down the caverns toward the interior and there found an underground pool for a refuge until they could return to the sunlight. I can think of no other excuse for water striders on the summit of Mount Washington.

This pool, of course, like a half score others that one can find on the very top of the summit cone after rain, was a mere puddle. But the Lakes of the Clouds are substantial bodies of water the summer through, and in the winter substantial bodies of ice, for they freeze to the bottom as soon as winter sets in. Water striders they have and larvæ of caddis flies and water beetles of many varieties, but never a fish swims in them, and I doubt if any other form of aquatic animal life ever wanders to their shores. Clear as crystal, shallow, ever renewed, they are but mirrors in which by day the peaks can see if their clouds are on straight and through which by night fond stars may look into the eyes of other stars near by without being noticed by envious third parties. Their source is the clouds, yet their waters are if possible clearer and even more sparkling than new fallen rain. Even the air above the highest peaks has its dust and soot which the rain washes out of it as it comes down. In the spring the snow at the head of the Tuckerman Ravine was dazzling in its pure whiteness. Now the dwindling arch is flecked with black; dust blown from the peaks above, soot washed to its surface from the sky by the rain, and without doubt also the cinders of burned-out stars that perpetually sift down to earth out of the void of space.

All this the rain brings out of the sky when it comes in deluge from the clouds to the peaks, but nothing of it does it take into the Lakes of the Clouds. The crushed rock through which it must filter on its way down the ledges takes out all impurities, and the mosses of the lower slopes aid the process. But they do more than that. By mysterious methods of their own the mountains aerate this rain water in its passage till it finally reaches the lakes, as it reaches all mountain springs, filled with a prismatic brilliancy that is all its own. Whether we assume these lakes to be eyeglasses of the slumbering giant which is the Range, or mirrors for the peaks and the stars, they are crystalline lenses of no ordinary brilliancy and power of refraction.

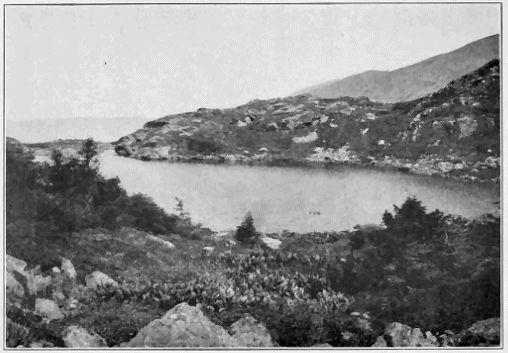

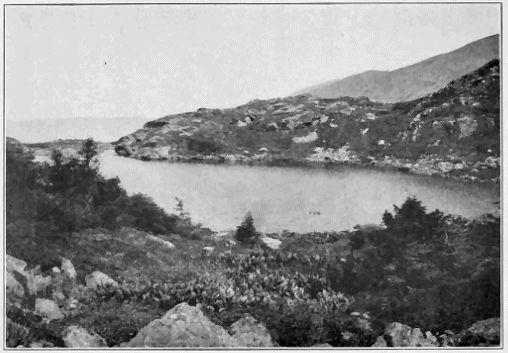

High as these tiny mirrors of the sky are, by actual measurement 5053 feet above the sea level, the highest lakes east of the Rocky Mountains, the tree line creeps up to them, and firs, dwarfed but beautiful in their courage, set spires along portions of their borders, dark, straight lashes for clear blue eyes. In other spots along their margin the ground is bluish early in the season with the leaves of the dwarf bilberry, pink-sprayed with their tiny, cylindrical petals of deciduous bloom, and, now that August is here, blue in very truth with the berries themselves. These are not large, but they are firm-fleshed and sweet as any lowland blueberry, and whether the flavor they have is inherent in themselves or draws its subtlety from the surroundings I am never sure, but as I sit among them and eat I know that it is worth the climb to their Alpine altitudes.

"Dwarfed firs, beautiful in their courage, set spires along portions of their borders, dark, straight lashes for clear blue eyes"

In the first part of the Alpine springtime, which comes to the Lakes of the Clouds with the early days of July, the country round about them was a veritable flower garden. The water in the lakes was ice water then, though the ice had disappeared from their surfaces and lingered only in the shadow of the low cliff which forms the southern boundary of one. Often the nights brought frost, and sometimes with the rain sleet sifted down as well. But little the dwellers in these Alpine heights care for these things. If the sun but shines it warms the tundra to their root tips and they push their blossoms forth to meet it with all speed. The geum flecked everything with yellow gold. In the crevices of the cliffs it clung where there was little but coarse gravel for its roots, and its radiate-veined, kidney-shaped root leaves flapped in the gales and were tattered in spite of their toughness. In such soil as the rocks gave the sandwort put forth tiny innumerable cups of white. Down in the tundra-clad slopes the geum throve as well, but there the white of the sandwort was replaced by that of countless stars of Houstonia. White and gold was everywhere in this flower-garden of the clouds, subtended here and there by the lavender delicacy of the Alpine violet, Viola palustris. Everywhere, too, was the honest, plebeian white and green of the dwarf cornel, and the æsthetic, green-yellow blooms of the Clintonia. It is strange that of two flowers that touch leaf elbows all through the woods of this northern country, high and low, one should be so hopelessly bourgeois as the Cornus canadensis and the other so undeniably aristocratic from root to anther as Clintonia borealis.

To tramp the slopes and hollows of this garden about the two lovely lakes is to alternate the rasping surface of pitted and weather-worn cliffs and scattered boulders of mica-schist with plunges half-knee deep in a soft and close-knit tundra moss. Here are mosses and lichens in close communion that ordinarily grow far apart. The sphagnums are to be expected, and they are plentiful, but with them grows the hairy-cap moss, sturdier and with larger caps than I often find it elsewhere. With these also grows the gray-green cladonia, the reindeer lichen, all massed in together in a springy sponge that holds water and plant roots and continually builds peaty earth. Because of this building of earth by the tundra mosses there are fewer Lakes of the Clouds than there were once. In half a dozen levels above and below the present lakes this constructive vegetation has built up a bog where once was open water, and makes tiny meadows for the quick-blooming plants of the mountain season.

Meadows of this sort climb from the Lakes of the Clouds up the ridge toward Boott's Spur, connected by underground rills and having little springs scattered through them where even in dry weather the thirsty may find good water. Up the side of the peak of Monroe they go as well, and it is not difficult to trace the moisture they hold by a glance from a distance, so green and pleasant does it make their flower-spangled surfaces. In the lowlands meadows are level or they are not meadows. On the mountains they sometimes run up at a pretty sharp angle and are meadows still.

In August the spring color scheme of white and gold stippled on the tundra moss by the geums, the sandwort and the Houstonia becomes blue and gold, built out of harebell blooms and those of the dwarf Alpine goldenrod, Solidago cutleri. There is much more of the gold than in the springtime and the blue of the harebells by no means is so prevalent as the white of Houstonia and of Arenaria. But clumps of Spirea latifolia put out their pale pink flowers in many nooks among the rocks and even insert patches of color among the dark firs that under the high banks of the lakes dare stand erect, though they are at the top of the tree line.

Most picturesque of all plants about the Lakes of the Clouds, in midsummer as in early spring, is the Indian poke, Veratrum viride. Next to the firs and spruces it spires highest, but unlike them it is of no obviously tough and hardy fibre. On the contrary, here is an endogenous plant, one of the lily family, that ought from its appearance to grow in a Florida swamp rather than on the great ridges of the Presidential Range, five thousand feet and more above sea level. Here is a place for low-growing Alpine plants like the sandwort, the Alpine azalea, the Lapland rose-bay, and the little moss-like Diapensis lapponica; and they grow here. But in the boggiest part of the tundra grows also this rank succulent herb, the Indian poke, spiring boldly with its light green stem, bearing three feet in air its big pyramidal panicle of yellowish green blossoms in early July, seed pods in middle August, but yellowish green and pyramidal still. Beneath the pyramid on the single stem stand the close-set, broadly oval, plaited and strongly veined leaves, and there the whole will stand till the freezing cold of October cuts down its succulent strength. The more I see of the Indian poke on Alpine heights the more I admire it. It does not quite reach the tip of the summit cone of Washington, but it climbs as near it as many a seemingly tougher fibred plant and would, I believe, reach as high as the sandwort could it have roothold in the necessary moisture.

Much has been written about the beauty of the Alpine Garden between the base of the summit cone of Washington and the head wall of Huntington Ravine. All that has been said of this and more is true of the rough rocks, the slopes, and the meadows about the two little Lakes of the Clouds. Traces of animal life indeed are rare on their borders. The most that I have seen was a deer that came at dawn over the ridge from Oakes Gulf, nibbled grass and moss in the meadows, drank from the larger lake, and bounded off again, leaving the tundra moss punctured by slender hoof marks. Birds are as numerous here as about those other wooded lakes of the clouds that lie below in the ravines, Hermit Lake in Tuckerman's and Spaulding at the head of the Great Gulf. I suspect the Myrtle and Magnolia warblers of building their nests in the dwarf firs not far from the shores, though I am unable to prove it. White-throated sparrows sing among the evergreens, though in August, in these altitudes, the white throats rarely give their full song. Often it is but a note or two and pauses there as if the bird were in doubt about the propriety of singing at this season. But the birds of the place beyond all others are the juncos. They sit on the bare ledges and sing, morning, noon and night, their gentle, melodious trill. It makes the place home to the listener at once as it is to the singers whose nests are tucked away in holes under many an overhanging stone along the ledges.

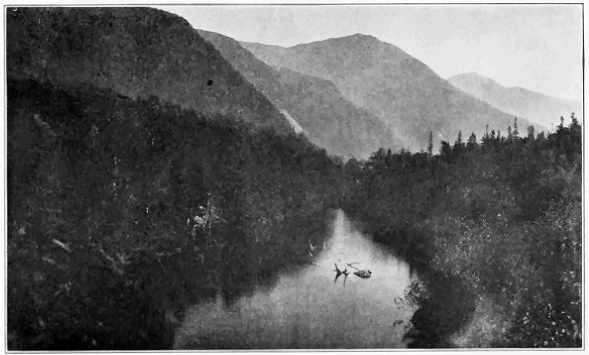

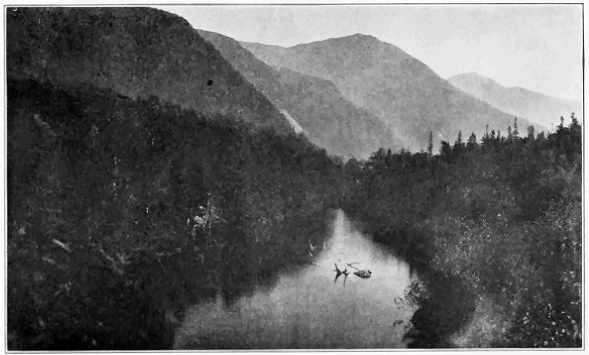

Spaulding Lake at the head of the Great Gulf, Mounts Adams and Madison in the distance

"The wind that beats the mountain blows more gently round the open wold" in which lie the two little Lakes of the Clouds. Into their tiny hollows the August sunshine wells and seems to tip with gold the plumes of the spinulose wood ferns which grow in the tundra moss and snuggle up against the mica-schist ledges that make miniature cliffs along the shores. Around the base of the mountain these ferns are everywhere, taking the place in higher altitudes of the Osmunda claytonia, which is the prevalent variety of lower lands. The progress of claytonia is interrupted not far from the entrances to the Gulf and to Tuckerman Ravine. Thence the Aspidium spinulosum goes on and is plentiful in many places up to and on the Alpine Garden. It makes the neighborhood of the Lakes of the Clouds beautiful with its feathery fronds and sends out to the lingerer in this beauty spot its ancient woodsy fragrance of the world before the coal age. Among all the beauties of the place it is hard to tell what is dearest, but I think, after all, the decision should be with the feathery, fragrant Aspidium spinulosum, the spinulose wood fern.

But for all their beauty by day and their cosy friendliness, the Lakes of the Clouds are at their best after nightfall. As the sunshine welled in them, so at dusk the purple shadows grow dense there and the shallows disappear. A boy can throw a stone across these lakes. He can wade them, but as the darkness falls upon them and the juncos pipe the last notes of their evensongs the little lakes widen and grow vastly deep. The farther shores slip away and become ports of dreams, and he who stands on the margin looks down no longer at bare rocks through transparent shallows, but into a universe of fathomless depth where star smiles back at star through infinite distances of blue. Who shall say it is not for this that the little lakes lie through the brief summer, clear mirrors under the shadow of the peak of Monroe?