XIII

CRAWFORD NOTCH

The Mighty Chasm in the Mountains and Its Perennial Charms

In the nick of the Notch—Crawford Notch—the narrow highway so crowds the Saco River that, tiny as it is, it has to burrow to get through, thereby meeting many adventures in a half mile. If Mount Willard had flowed over to the north just a few rods farther, when it was fluid, there would have been no Notch, but only a gulf like that between Washington and the northern peaks, or like Oakes Gulf, barred completely by the vast head wall of metamorphic rock. It came so near that originally there was room only for the Saco to pass down, a slender stream, new-born at the shallow lake on the plain just above. Then the famous old "Tenth Turnpike" of New Hampshire came along and by smashing away the rock and crowding the Saco men made a way through for it. As for the railroad, its case was hopeless. It had to burrow a nick of its own through the base of Mount Willard, and out of the débris of this blasting the road makers built a series of fantastic rock piles, monuments to the heathen deities of Helter-Skelter, which serve to make the gateway in which these three jostle one another, road, railroad and river, more weird even than it was before.

But the gateway is as beautiful as it is fantastic. The road south to it comes along a smiling plain and the mountains draw in to meet it, indeed as if to bar it. On the left Mount Clinton sends down two long ridges between which flows Gibb's Brook. On the right Mount Willard shoulders its rough rock bulk boldly into the way, and down these the spruces stride like tall plumed Indians come to bar the passage of the white man. But the road winds on and just as it seems as if it must stop it finds a way and, fairly burrowing as does the river, flows down the Notch. With the rocks alone the gateway would be a forbidding tangle of débris. Clothed in the hardwood growth, it would be but a greenwood gap. But these pointed spruces and the firs that mingle with them bring to it an architectural dignity of pillars and spires, a jutting of Gothic pinnacles, a suggestion of Ionic columns, that makes it the gateway of a vast woodland cathedral, a place through which one passes to worship and be filled with awe and veneration of the mighty forces that shaped it.

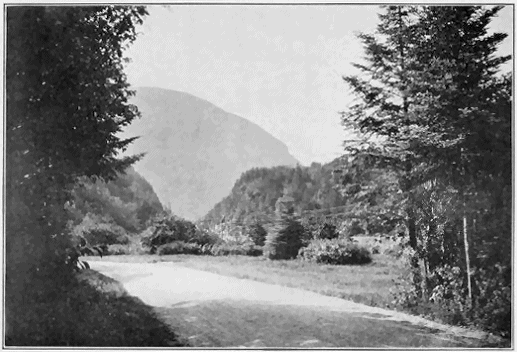

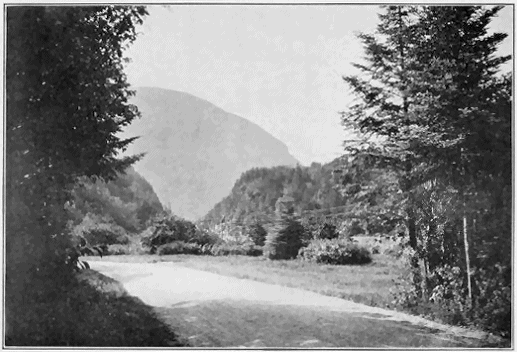

"Profile of Webster," looking toward Crawford Notch from the old Crawford farm-house site

It is a cathedral that has its gargoyles, too; everywhere through the spiring spruces and the softening outlines of deciduous trees protrude the rocks in fantastic shapes that show strange creatures to the imaginative onlooker. Just at the gateway, lumbering out from the mountain, comes an elephant, head and trunk, little eye and flapping ears plainly visible, poised in granite, but ready at any moment to take the one step onward that will reveal the whole gigantic animal standing in the roadway. Beyond, the whole left side of the Notch shows a gigantic face, the mountain's brow itself a noble dome of thought, the nose huge and Roman, and the whole weird and misshapen, but not without a strange dignity of its own. And so it is with the whole formation of the Notch. Its once molten rocks cooled or have been water-worn into strange forms that greet the eye of the imagination at every turn. It is well that the narrow turnpike flows so swiftly down into the depths of the wood and hides the traveller from the sight of too many portents. To get down the nick of the Notch just a little way by road is to be shaded by the overhanging deciduous growth and to be able to forget, as does the Saco, the crowding together of those weird forms carved by the ages from enduring granite.

The railroad hangs to its grade on the mountain side, but the road descends rapidly, though not so rapidly as the river that, here a little released from its pressure between the two, comes to sight again and slips in purling shallows or babbles down miniature cascades, the thinnest of slender streams, to the depths of a shaded cleft in the cliffs known as "The Dismal Pool." Dismal this may be to look at from the height of the train as it winds along the steep face of the Mount Willard cliff. But it is not dismal when one gets down to it, in the very bottom of the nick of the Notch. In places rough gray cliffs, in others black spruces, climb one another's shoulders from this little level of grass and placid water where flows the Saco. A pair of spotted sand-pipers make this their home and they did not resent my coming to join them. Instead they bobbed a greeting and then went on industriously picking up dinner, wading leg deep in the shallows and often putting their heads as well as their long bills under water in search of food. Spotted sand-pipers nest in the summer from Florida to Labrador, but I fancy no pair has a finer home than this little pool in the very bottom of the vast cleft in the mountains which is Crawford Notch. Its shores were netted with the tracks of their nimble feet.

No other bird track was there, but the sand-pipers by no means monopolize the borders of this shallow water. Here were the marks of hedgehog claws, and there was a track which led me to pause in astonishment. What plantigrade had set foot of such size on the soft sand of the shore? I looked over my shoulder after the first glimpse, half expecting to see an old bear, for here was what looked very like the track of a young one. A second look told me better. This footmark, not unlike that of a human baby, save for the claws, was no doubt that of a raccoon, but certainly the biggest raccoon track I have seen yet. It was perfectly fresh, and I dare say the owner, interrupted in his frog hunt by the sound of my scrambling approach beneath the black growth, had but then shambled to some den in the nearby cliffs and was impatiently awaiting my departure.

The flower of the place was the little, herbaceous St.-John's-wort, Hypericum ellipticum, in whose linear petals such sunlight as reached the bottom of the cleft seemed tangled. It grew everywhere on the narrow margin between the black shade of the spruces and the clear, shallow water, and its petals shone out of a soft mist of tiny white aster blooms in many places. Farther up stream, and indeed in most woodland shadow throughout the Notch, grows the Eupatorium urticæfolium, which, though its common name is "white snake root," is nevertheless the daintiest of the thoroughworts. Its flowers are a finer, whiter fluff of mist than are those of the aster, so plentiful on the shore of the not dismal pool and which I take to be aster ericoides. In late August they seem to me quite the most beautiful flowers of the Notch woodlands. In this I do not except the blue harebells which grow so plentifully on the sandy flats down by the Willey House site. Above the tree line the harebells are beautiful. Here they are straggling and pale and are not to be compared with their hardier, sturdier sisters.

As railroad, highway and river draw together and touch elbows in passing through the gateway of the Notch, so do all other tides of travel. Here in spring should be the finest place in the world to see all migrant birds on their way farther north. The valley of the Saco catches them as in the flare of a wide tunnel and gradually draws them together here. At certain corners in London all the world is said, sooner or later, to pass. So at the gateway of the Notch one should see in May and June all north-bound varieties of birds. Even at this time of year the wandering tribes concentrate at this spot and bird life seems far more plentiful than at any other equal area in the mountains. On the bare heights of the Presidential Range, which I had been travelling for long, the juncos are one's only bird companions. Here in deep forest glades variety after variety passed singing or twittering by. Here were robins, song sparrows, chipping sparrows, white-throated sparrows, chickadees in flocks. Red-eyed vireos preached in the tops of yellow birches. A yellow-throated vireo twined and peered among the twigs, gathering aphids. Here were myrtle and magnolia warblers and a blackpoll, all residents in the neighborhood without doubt, but all on their way, and seen in a brief time.

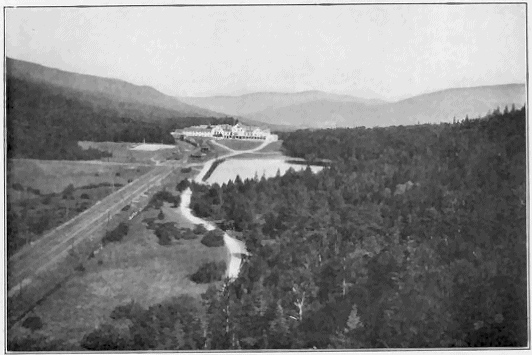

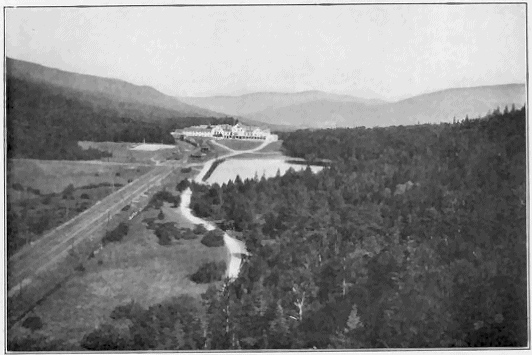

"Where railroad, highway, and river draw together and touch elbows in passing through the gateway of the Notch"

Most pleasing of all to me was a strange new chickadee voice which sang something very like the ordinary black-capped chickadee song, but with a slower and far different intonation. I followed the maker of this old song with new words over some very rough country, from one side of the Notch just below the nick to the other, for I was very eager to see him. By and by I found him with others of his kind swinging head down from twigs, climbing and flitting in a fashion that is that of all chickadees, but had a quality of its own, nevertheless. Here was a flock of chickadees, with less of nervousness in their manner and a little more poise, if I may put it that way, than the blackcaps have, chickadees with brown crowns instead of black, and, I thought, a little more of buff in their under parts. All summer I had looked for the Hudsonian chickadee on one mountain slope after another, and I had not found him. But here in the nick of the Notch a flock had come to me and I did my best to see and hear as much as possible of them. They, too, were on their way, but were probably residents of the neighborhood, for I took them to be one family, father, mother and five youngsters, just learning to forage for themselves. This they did in true chickadee fashion, swinging and singing, flitting and sitting, and always following and swallowing food, to me invisible, with great gusto.

The song was what pleased me most. One authority on birds has written it down in a book that the song of the Hudsonian chickadee is not distinguishable from that of the blackcap, though uttered more incessantly. Another, equally reliable, says the notes are quite unlike those of the blackcap. My Hudsonian chickadees sang the blackcap's song, but they sang it a trifle more leisurely and with a bit of a lisp. But that is not all. There is something in the quality of the tone that reminded me at once of a comb concert. It was as if these roguish youngsters had put paper about a comb and were lustily singing the prescribed song through this buzzing medium. It may be that other Hudsonian chickadees sing differently. Birds are intensely individualistic, and it is hardly safe to generalize from one flock. This may have been a troupe doing the mountain resorts with a comb concert specialty and tuning up as they travelled, as many minstrels do, but the results were certainly as I have described them. I am curious to see more birds of this feather and see if they, too, conform, but I fancy Crawford Notch is about the southern limit of the variety in summer, and I may not hear another serenade in passing. These certainly found me as interesting as I did them. They fearlessly flew down on twigs very near me and looked me over with bright eyes, the while talking through their combs about my characteristics and how I differed from the Hudsonian variety of man. It was a genuine case of mutual nature study.

Very cosy all these things made the nick of the Notch, but now and then as I scrambled through its rough forest aisles the mountains looked down on me through a gap in the trees, frowning so portentously from such overhanging heights that I was minded to jump and flee from the imminent annihilation. For, after all, the beauty of flowers and the friendliness of birds, the architectural decorations of the firs and spruces, even the monster semblances of the rock carvings that overhang, are but the embroidery on the real impression of the Crawford Notch. To get this it is well to go down the long slope of the highway, ten miles and more, till you emerge below Sawyer's River where Hart's Ledge frowns high above Cobb's Ferry. Thus you shall know something of the length of this tremendous fold in the rock ribs of the earth. Here is no work of erosion alone. The Notch was made primarily by the bending of the granite of the mountains that rise in such tremendous sweeps on either side to heights of thousands of feet. On most of their swift-slanting sides some dirt and débris of rock has accumulated and the forest has clothed them, but this clothing is thin and in many places the slant is so swift and the surface so smooth that the rock lies bare to the sun, and all streams have swept it clean. In August little water comes down these, but there is the bare channel of brown rock up which one may look from the highway, taking in the whole sweep of a stream at a glance. At the bottom of these swift glissades the tangled piles of smashed rocks show with what force the waters come down when floods push them.

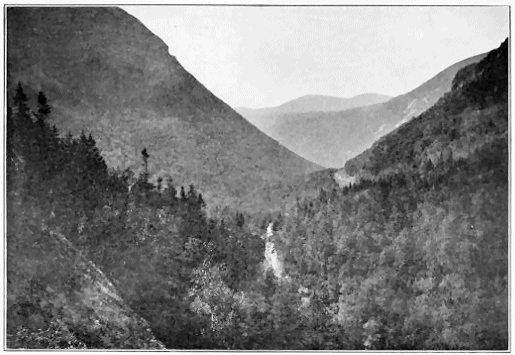

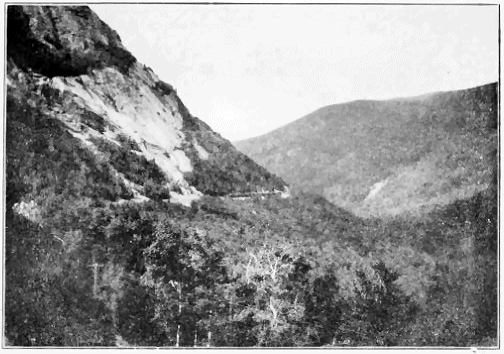

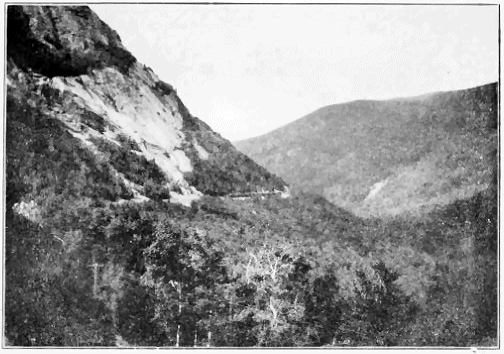

"Just below the nick of the Notch you may see where the Silver Cascade and the Flume Cascade hurry down from their birth on Mount Jackson, and farther down the vast slope of Webster"

Thus just below the nick of the Notch you may see where the Silver Cascade and the Flume Cascade hurry down from their birth on Mount Jackson, and farther down the vast slope of Webster is swept clear in great spaces where now only a little water comes moistening the upper rim of rocks, spreads, and evaporates before it has passed over the slanting, sun-heated surface. All the way down the glen, to the Willey House, to Bemis, and on to Sawyer's River, one looks to the right and left up to rock heights swimming more than a thousand feet in air, bare, immanent, cleft and caverned, and often carved to strange semblances of man or beast. Crawford Notch is a veritable museum of gigantic fantasies.

Most impressive of all it is to pause at the site of the Willey House and look back toward the gateway of the Notch, through which you have come. Here the mighty bulk of Mount Willard lifts sheer from the tree-carpeted floor, six hundred and seventy feet in air, a mountain that once in semi-molten form flowed into place across the wide valley and blocked it with a solid rock, overhanging, seamed and wrinkled, showing projecting buttresses and withdrawing caverns, a rock so solidly knit and compact that the wear of the ages on it has been infinitesimal. On the summit of this cliff are the hammer marks of frost. These blows and the solvent seep of rain may take from the mountain a sixteenth of an inch in a hundred years, but the disintegrating power that splits ledges and hurls hundred-ton rock from precipices seems never to have worked on this cliff, so perpendicularly high and mighty does it stand.

First or last the visitor to the Notch will do well to climb Willard and see it as a whole. An easy carriage road makes the ascent, stopping well back from the brow of this tremendous cliff. Willard is hardly a mountain. It is rather a spur, a projecting ledge of the Rosebrook Range, whose peaks, Tom, Avalon and Field, tower far above it. But on this great ledge of Willard one is swung high in air in the very middle of the upper entrance to the Notch. Hundreds of feet of it are above him still, but thousands are below, and he looks down the tremendous valley as the soaring eagle might. Soothed by distance the rough valley bottom seems as level as a floor, its forest growth but a green carpet on which certain patterns stand out distinctly, the warp of green deciduous growth being filled with a dainty woof of fir, spruce and pine. To the left the bulk of Webster blocks the horizon.

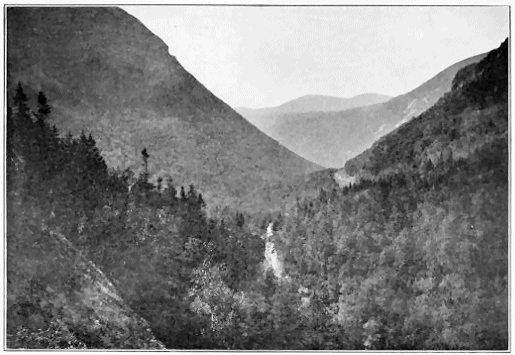

In the heart of Crawford Notch, the summit of Jackson on the distant horizon

To the right the glance goes by Willey and on down to Bemis and Nancy, and the blue peaks of other more distant mountains that peer over them. From the head wall of the Great Gulf, looking down between Chandler Ridge and the Northern Peaks of the Presidential Range, one gets a view of a wonderful mountain gorge. The outlook from Mount Franklin, down the mighty expanse of Oakes Gulf to its opening into the Crawford glen below Frankenstein Cliff is, to me, more impressive still. But greatest of all in its beauty of detail and its simplicity of might and grandeur is this ever-narrowing, ten-mile chasm, this mighty, deep fold of rock strata that begins below Sawyer's River and ends where the enormous rock which is Mount Willard so pinches the gateway to the Notch that the railroad burrows, the highway excavates and the tiny brook which is the beginning of the Saco River dives out of sight between the two, to reappear in that "dismal pool" which lies at the very bottom of the nick of the Notch.