XV

CARRIGAIN THE HERMIT

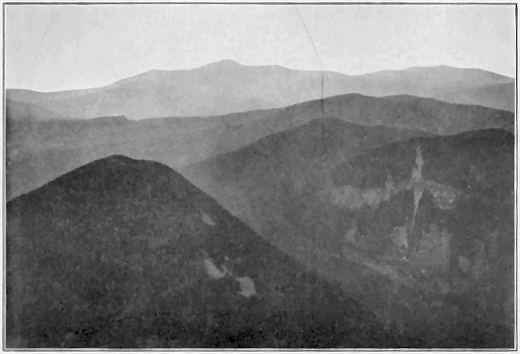

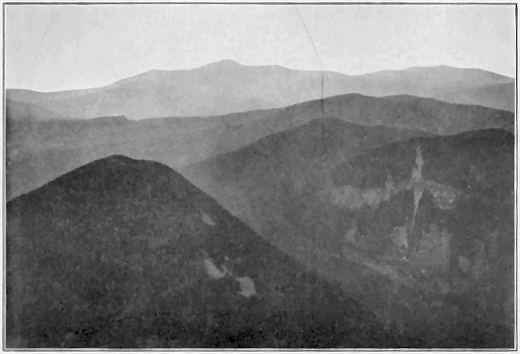

The Mountain and Its Overlook from the Very Heart of the Hills

On no peak of the White Mountains does one have so supreme a sense of uplift as on Carrigain. Here is a mountain for you! No nubble on top of a huge table-land is Carrigain but a peak that springs lightly into the unfathomable blue from deep valleys of black forest. So high is this summit that from it you look through the quivering miles of blue air right down upon the mountains in the heart of whose ranges it stands and see them reproduced in faithful miniature below, a relief map on the scale of an inch to the mile. In the very middle of the mountain world you see the mountains as the eagle sees them, and so isolated is the peak that like the eagle you seem to swim in air as you watch.

The black growth of spruce and fir climbs Carrigain from all directions. Over from Hancock it swarms along the ridge from the westward. From the Pemigewasset it sweeps upward, and from Carrigain Notch it leaps twice, once to the round summit of Vose Spur, a clean bound of almost two thousand feet, then on to another higher point, and again to the mountain top. Up Signal Ridge from the east and south it scales almost perpendicular heights for a mile, leaving only the thin, dizzy edge of this spur bare and going on by the sides to the top of the main mountain. The path to the summit makes its final assault through this black growth to the knife edge of Signal Ridge by one of the most desperately perpendicular climbs in the whole region. One or two trails are steeper, a little, notably part of that from Crawford Notch up Mount Willey, but none holds so grimly to its purpose of uplifting the climber for so great a distance as does this. Four and a half miles of pleasant journey in from the railroad station at Sawyer's River, this mighty ascent begins a strong upward movement at the old lumber camp known as "Camp 5." Thence for about two miles it goes up in the air at a most prodigious angle, with no suggestion of let up till the dismayed and gasping climber finally emerges on the knife edge of the ridge summit and willingly forgives the mountain for all it has done to him. If the climb had no more to give than just this outlook from Signal Ridge it were worth all the heart failure and locomotor ataxia it may have caused.

Right under the onlooker's feet the north side of the ridge drops away almost sheer to the deep gash in the mountain, which is Carrigain Notch. Across the valley rises the sheer wall of Mount Lowell, with a great, beetling cliff of red rock half way up intersected by a slide, the whole looking as if giants had carved a huge, preposterous figure of a flying bird there for a sign to all who pass. The summit of Lowell is far below the observer's feet, and the whole mass is so small a thing in the mighty outlook before him that it seems ridiculous to call it a mountain. It is but an insignificant knob on the universe in sight.

"As if giants had carved a huge, preposterous figure of a flying bird there for a sign to all who pass"

Over beyond its rounded summit rise others, little larger or more significant, though each really a mountain of considerable size, each part of the western wall of Crawford Notch, Anderson, Bemis and Nancy, and beyond again the sight passes between Webster and Crawford, on and up the broad expanse of Oakes Gulf to Washington itself. Here always is bulk, magnificence and dignity, and between it and the nubbles which mark the line of the southern peaks rises a glimpse of the northern, Jefferson peering over Clay, but Adams and Madison withdrawn behind the looming bulk of the summit cone of Washington. Between Washington and Crawford runs the long Montalban Ridge with the Giant Stairs conspicuous as always, but dwarfed to pigmy size in the great sweep of the whole outlook.

Easterly is a great jumble of the mountains south of Bartlett, Tremont in the foreground and over that Bartlett-Haystack, Table with its flat top, the peaked ridges of the Moats, and beyond them all the perfect cone of Kearsarge on the eastern horizon. There is something of the same feeling of supreme uplift to be felt on the summit of Kearsarge as one gets on Carrigain, though in lesser degree. Kearsarge, too, is a mountain that dwells somewhat apart from other mountains and gives the climber the full benefit of this height and withdrawal. As the glance swings to the southward again it stops in admiration on the blue wall of the Sandwich Mountains, the great horn of Chocorua first arresting the gaze. Here is a splendid outlook upon the full sweep of this great, jagged range, Paugus, Passaconaway, Whiteface, Tripyramid and Sandwich Dome, each rugged peak rising out of the blue mass of the whole, with the green Albany intervales along the Swift River showing below their foothills, and over it all, far to the south again, the low line which is the smoke haze of cities, a brown brume behind the exquisite soft blue of the uncorrupted mountain miles of air.

At the bottom of a scintillant blue transparency of this air lies the high valley between Signal Ridge and the Sandwich Range, a mountain valley with no hint of green fields or farm steadings in it. Its green is that of the rich full growth of leaves in deciduous treetops, shadowed here and there by the point of a fir or a spruce, still strangely standing, though the lumbermen have long since swept the valley far and wide. Almost one may determine the exact height of spur cliffs above the valley bottom by the line of black growth where it has escaped the axe, not because axemen could not reach it, but because horses could not be found to drag it to the valley after being cut. The lumbermen put their horses in upon acclivities now that were thought to be forever inaccessible twenty years ago, but there are still heights they do not dare, and the lines beyond which they fail are marked along all steep slopes by that dividing line between the green of deciduous trees and the black of spruce. Seen from the great height of this knife-edge ridge the valley is grotesque with its lifting crags of rough cliff, so solidly built of rock that no green thing finds a crevice in which to grow, or so steep as to defy any wind-borne seed to find a lodging there. These rough rock cliffs have grotesque resemblance to the shaggy heads of prehistoric animals of more than gigantic size that seem to have been turned into stone where they lie, their bodies half buried and concealed by the luxuriant growth of forest that still surges round them. A lumber company is known by its cut. The work done here seems to have been done with a certain feeling of fair play to the forest, a desire to give it a chance to ultimately recover. Westward, deeper into the heart of the wilderness, one sees another record.

To see the west one must climb beyond Signal Ridge. High as it is it is but a spur of the main mountain that looms, spruce-clad, all along the western sky, and the path rises steeply again through this spruce, but not so steeply as it climbed the ridge. Midway of the half-mile one finds the tiny log cabin of the fire warden of the mountain, snuggled beneath the spruce behind the shoulder of the ultimate height. Whatever this lone watcher on the mountain top is paid he earns, for all furnishings for his tiny cabin, all supplies, even water, must be packed on his back up the two miles of dizzy trail.

On Carrigain's very top is a little bare spot surrounded by dwarf spruce and fir over whose tops you may look upon the world around. The dark tree walls of this roofless refuge ward off all winds, and the full sunshine fills it to the top and seems to ooze thence through the black growth and flow on down the mountain sides, which are so near that a few steps in any direction takes you to a spruce-clad precipice. Some mountain tops are broad and flat enough to form the foundation for a farm, but not this one. It is a veritable peak. Signal Ridge is a good deal of a knife edge. Here you have the edge prolonged into a point.

A step or two west out of this sun-filled spruce well of refuge on the summit takes one to the finest view of all from this swimming mountain top. Underfoot lies the broad wilderness valley of the Pemigewasset, filled with what, from this point of view, are minor nubbles, but which really are lesser mountains. Just to the right, far below, is a whole string of three thousand-foot eminences, yet the sight passes over them, almost without notice, to the magnificent gap in rock walls, which is Zealand Notch. Almost due west is Owl's Head and half-a-dozen lesser heights, but all these sink unnoticed below the blue wall of solid mountain range which blocks the horizon above them, the tremendous uplifted bulk of the Franconia Mountains. Not the grandeur and dignity of Washington, lifting the sphinx's head from the Presidential Range, not the jagged line of the Sandwich peaks cutting with points of distance-blued steel the smoke opalescence of the far southern sky, not the emerald marvels of all the low-lying ranges all about, can compare in beauty or impressiveness with that mountain mass of solid blue that walls the west across the rugged miles of the Pemigewasset Valley. Its great mass of unblurred, undivided color holds the eye for long and gives it rest again and again after wandering over the thousand varied beauties of the surrounding landscape. Lafayette, Lincoln, Haystack, Liberty are its famous peaks, which, however they may seem upon nearer view, from the dizzy pinnacle of Carrigain, across the broad wilderness of the Pemigewasset Valley, hardly notch the sky that pales above that mighty wall of deep blue, that restful mass of immensity, that unfathomable well of richest color that once looked into holds the eye within its shadowy coolness for long and stays forever in the memory.

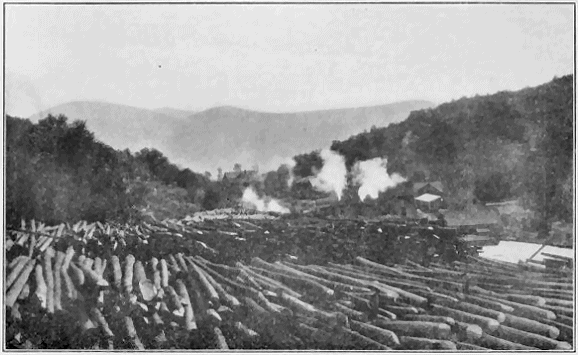

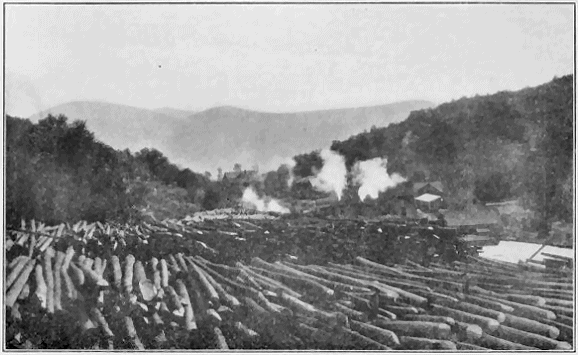

What a world of black-growth wilderness this vast Pemigewasset Valley must once have been it is easy to see. What it will become in just a few years more, alas! is too easy to be inferred. The modern lumberman comes to his work equipped with all the vast resources of capital and scientific machinery. In this region west of Carrigain, which still holds a remnant of virgin growth of pine and spruce, where still stand trees four or five feet in diameter at the butt, his logging trains rumble down his railroad through the deep woods, summer as well as winter. The sound of dynamite explosions scares bear and deer as his road builders grade and level the roads down which his armies of men and horses will haul the splendid timber as soon as the snow flies. From Carrigain summit I see the long winding line of his railroad, clear up to the western slopes of the mountains that wall in Crawford's Notch. From the railroad to the right and the left run the carefully graded logging roads, high up on the sides of the surrounding mountains, branching, paralleling and giving the teams every opportunity for careful, methodical work.

Already over square miles of mountain sides you see the brown windrows of slash left in the wake of his choppers, who have left literally not one green thing. The black growth cut for the lumber and pulp mills, the clothes-pin men and the makers of ribbon shoe pegs have been in and taken the last standing scrub of hard wood. Mountain side after mountain side in this region looks like a hayfield, the brown stubble marked with those long, wavering windrows of slash. These are the newly cut spaces. One winter's work took out of this region over thirty million feet of pine and spruce alone. There is written on the open book of the forest below Carrigain the story of the most ruthless, clean-sweep lumbering that I have ever seen in any wood. You may go down the Pemigewasset and see the slopes that have been cleaned out thus over square mile after square mile of mountain side, four, eight, twelve years ago, and, save for blueberries, blackberries and wild cherry trees, they are as bare and desolate to-day as when first logged.

"Nor is this to be said in any scorn of the lumberman. He bought the woods and is using them now for the purpose for which he spent his money"

In a hundred years those slopes will not again bear forests; indeed, I doubt if they ever will. Nor is this to be said in any scorn of the lumberman. Pulp and lumber we must have. He bought the woods and is using them now for the purpose for which he spent his money. The scorn should rather be for a people who once knew no better and who, now that their eyes are opened, still allow this priceless heritage of ancient forest to be swept away forever.

It is good to shift the eye and the thought from these bare patches to the still remaining black growth. Fortunately some steeps still defy the keenest logging-gang and some spruce will remain on these after another ten years has swept the valley clean. On the high northern slopes, well up toward the peaks, where the deer yard in winter, the trees are too dwarf to tempt even the pulp men, who take timber that is scorned by the sawmill folk. On the summit of Carrigain trees a hundred years old and rapidly passing to death through the senile decay of usnea moss and gray-green lichens are scarcely a dozen feet tall. Yet as these pass the youngsters crowd thickly in to take their places and grow cones and scatter seed, often when only a few feet high. In these one sees a faint hope for the reforestation of the valley in the distant future. There, after the clean sweep, we may allow fifty years for blueberries and bird-cherries, a hundred more for beech, birch and maple to grow and supply mould of the proper consistency from their falling leaves in which spruce and fir seedlings will take root. After that, if all works well, another hundred will see such a forest of black growth as is going down the Pemigewasset daily now on the flat cars of the logging railroad.

Carrigain's peculiar birds seem to be the yellow-rumped warblers, at least at this season of the year. They flitted continually through and above the dwarf trees of the summits. There they had nested and brought up their young, and now the whole families were coming together in flocks and beginning to move about uneasily as the migration impulse grows in them. All along the trail up Carrigain and back I found this same spirit of movement in the birds. Two weeks ago they were moulting and silent. Hardly a wing would be seen or a chirp heard in the lonesome woods. Now all is motion in the bird world once more and flashes of warbler colors light up the dark places with living light. Among these black spruces the redstart seems to me loveliest of all. No wonder the Cubans call him "candelita" when he comes to flit the winter away beneath their palm trees. His black is so vivid that it stands clearly defined in the deepest shadows and foiled upon it his rich salmon-red flames like a wind-blown torch as he slips rapidly from limb to limb, flaring his way through the densest and deepest wood. The myrtle warblers were the birds of the summit, but the redstarts gave sudden beauty to the slopes all along the lower portions of the trail.

The sun was setting the deep turquoise blue of the Franconia Range in flaming gold bands as I left the mountain top. The peak of Lafayette was a point of fire. Garfield, just over the shoulder of Bond, was another, and it seemed as if the two were heliographing one to another from golden mirrors. But along the knife edge of Signal Ridge lay the shadow of Carrigain summit and the dwarfed growth down the two miles of steep descent was black indeed. Hardly could the sunlight touch me again, for the trail lies in the eastward-cast shadow of Carrigain all the way to Sawyer's River. The evening coolness brought out all the rich scents of the forest, for here to the east of Carrigain the deciduous growth makes forest still. From the heights the rich aroma of the firs descended with me, picking up more subtle scents on the way. Not far below the crest of Signal Ridge the mountain goldenrod begins to glow beside the trail. Scattered with it is the lanceolate-leaved, flutter-petalled Aster radula. These two lent to the aromatic air the subtle, delicate pungency of the compositæ, and far below, in the swampy spots at the foot of the declivity, the lovely, violet-purple Aster novæ-angliæ added to it. Here in open spots beside the trail this beautiful aster starred the gloom for rods, but yet it was not more numerous than the rosy-tipped, white, podlike blooms of the turtle-head that in the rich dusk glowed nebulously among them. Nowhere in the world do I remember having seen so many turtle-head blooms at one time as in the marshy spots along the trail leading toward Livermore and Sawyer's River from the base of Signal Ridge. Their soft, delicate perfume began to ride the fir aroma there, mingling curiously with the scent of asters and goldenrod. Often I looked back for a glimpse of the lofty peak I had left, but Carrigain is indeed a hermit mountain. It had withdrawn into the heart of the hills which are its home, and nothing westward showed save the rose-gold of the sunset sky which hung from the zenith down into the gloom of the woods, a marvellous background for the tracery of its topmost leaves.