XVI

UP THE GIANT'S STAIRS

The Back Stairs Route up this Curious Mountain

My way to the Giant's Stairs lay over the high shoulder of Iron Mountain, where the road shows you all the kingdoms of the mountain world spread out below, bids you take them and worship it, which perforce you do. Then it swings you down by a long drop curve into a veritable forest of Arden, through which you tramp between great boles of birch and beech for miles. Here long ago Orlando carved his initials with those of Rosalind on the smooth bark of great beech trees and, I doubt not, hung beside them love verses which made those pointed buds open in spring before their time. Here came Rosalind to find and read them, and carry them off treasured in her bodice, wherefore one finds no traces of them at the present day.

"My way to the Giant's Stairs lay over the high shoulder of Iron Mountain, where the road shows you all the kingdoms of the mountain world spread out below"

Yet the carven initials remain, as anyone who treads the road beneath these ancient greenwood trees may see. Little underbrush is here and no growth of spruce or fir, and one may look far down arcades of green gloom where the flicker of sunlight through leaves may make him think he sees glints of Rosalind's hair as she dances through the wood in search of more poems. The long forest aisles bring snatches of joyous song to the ear, nor may the listener say surely that this is Rosalind and that a wood warbler, for both are in the forest, one as visible as the other. The whole place glows with the golden glamour of romance, and he who passes through it, bound for the Giant's Stairs, thrills with the glow and knows that his path leads to a land of enchantments.

By and by the trail drops me down a sharp descent, and at the bottom I find, close set with alders, a tiny clear stream which soon babbles out from beneath the bushes into another of those forest aisles; and there is a little house in the wood, so tiny and so picturesquely a part of its surroundings that, though it purports to be a hunter's camp, I know it at once for that little house which Peter Pan and the thrushes built for Wendy. But the song of the brook, this Serpentine of the deep woods, is a lonesome one, for the door of the little house is locked and the shutters are up. If I remember rightly Wendy went away and never came back, and Peter Pan is so rarely seen, now-a-days, that few people really believe he is to be found at all. But at least here is his house, on a tributary to Rocky Branch Creek, over northwest of Iron Mountain.

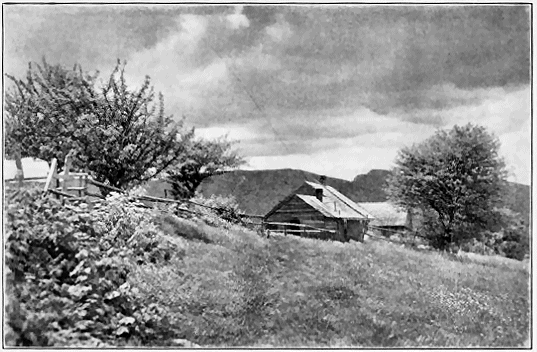

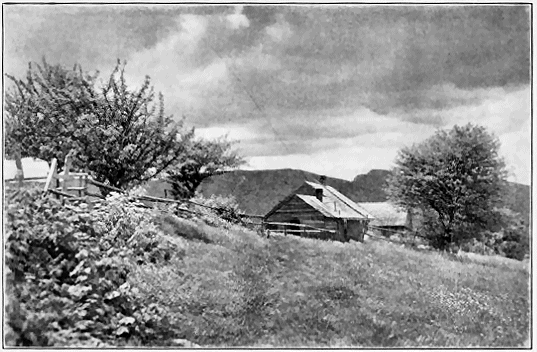

Out of the illusory gloom of the brook the path leaps with joy to the clear sunlight of open fields and seems to stop at an old doorstone behind which the ruins of a house still strive to shelter the cellar over which they were built. Floors and sills are gone, boarding and shingles and upright timbers have fallen, but still the oak pins hold plates and rafters together, and the bare bones of a roof crouch above the spot, so sturdy was the work of the pioneers that here hewed a home out of the heart of a forest. Between this spot and civilization is now only a logging road for miles, and the presence of these open, sunny fields in the deep forest, and among rough hills, seems almost as much an illusion as the echoes of the voice of Rosalind in the deep woodland glades and the thrush-built house of Peter Pan by the brookside. But here they stand in this cove of the mountains, field after field, still holding out against the sweep of the forest that for half a century has done its best to ride over them, still loyal to the dreams of whose fabric they were once the very warp. The old highway, too, still loiters from farm to farm, though the wood shades it and in places even sends scouting parties of young trees out across it. The growing maples push the top stones from the old stone walls, brambles hide the stone heaps and fill cellar holes with living green. Yet still the apple trees hold red-cheeked fruit to the sun from their thickets of unpruned growth and scatter it in mellow circles on the ground for the deer and the porcupine. The forest will in time make them its own. It will shade out the European grasses that still grow knee deep and fill their places with dainty cedar moss and the shy wild flowers of the deep wood. Yet for all that the trail of the pioneers, the boundaries that they set and the work of their hands will never be quite disestablished on the spot. It will remain for long years to come a sunny footprint of civilization, dented deep in the surrounding green of the wilderness.

Down one gladed terrace after another, from one farm to the next, the old road goes, and the path, which seems to linger at the first doorstone, slips finally away and follows between the ancient ruts. Through gaps in the investing forest I look far down the Rocky Branch Valley to the blue of Moat Mountain, a color so soft that it makes the great mass but a haze of unreality to the perceiving senses. If a wind from the west should come up and blow it away, or if some scene shifter of the day should wind it up into the sky above, just a part of a beautiful drop curtain, I should hardly be surprised. I do not care to climb Moat, if indeed there be really such a mountain. All summer it has hung thus, a soft haze of half reality, a mountain painted on some portion of the view from whatever hill I climb, its contour changing so little from whatever direction I view it that it seems what I prefer always to keep it, the blue fabric of a half-wistful dream. So shall it be more permanent and in time more real than many a higher summit, the grind of whose granite has left its mark upon me. It is the unclimbed peaks which are eternal.

From the last terrace of the lowest farm the trail drops suddenly to Rocky Branch, a tributary of the Saco which has its rise in a deep angled ravine far up on the southerly slope of Mount Washington. Here is a choice of ways, a good tote road, a logging railroad, and a broad, graded logging road which the lumbermen are dynamiting through to the last spruce of the valley, up at the headwaters of the branch. From these highways broad logging roads give me a plain trail up the steep Stairs Brook Valley to the bottom step in those mighty stairs. He who would know what lumbermen can do in logging precipitous spots may well look about him here. The ground rises at tremendous angles from the ravine bottom to the foot of Stairs Mountain, and on, yet down these precipices the woodsmen have brought their log-laden teams safely, the sleds chained and the whole load lowered inch by inch by snubbing lines. To note the spots into which men have worked is to have a vivid impression of the value of spruce and the desperate lengths to which men will go to get it now-a-days.

The Giant's Stairs are more in number than the two great ones that appear to the eye from a long distance, either east or west. Northeast of these a half mile or less is a side stair, as big and as steep as the ones most commonly seen, and farther on around the mountain toward the north are others. It was these back stairs that I climbed, all because of a yellow-headed woodpecker that flew by the ruins of the logging camp which are not far from the base of the side stair. I got a glimpse of the yellow crown patch and of some white on the back or wing bars, but whether it was the Arctic three-toed woodpecker or the American I could not make out, and I followed his sharp cries and jerky flight up the steep slope to the right of the side stairs. Here was an astounding tangle of windrowed slash with many trees still standing in it, and here for a long time I got near enough to my bird to almost make sure which variety he was, but not quite. It is hard to distinguish markings, even black and white, when a bird is high on a limb against the vivid light of a mountain sky. It is easy to follow along the parallel roads through which the logs have come down out of the slash, but it is another matter to struggle from one road to another across those mighty tangles, and thus my woodpecker led me. Finally at the very top of the col between Stairs Mountain and its outlying northeasterly spur he shrieked, quite like a soul in torment, and flew away high over my head, straight toward the summit of Mount Resolution, leaving me somewhat in doubt as to whether he was Picoides Arcticus or Picoides Americanus, or a goblin scout sent out by the giants to toll strangers away from the easier path up their mountain and lose them in the wilderness tangle all about it. Whatever he was he had led me some miles round the mountain to a point exactly opposite to the good path up.

The back stairs are formidable enough to dismay anyone with mere human legs, and for some time I wandered in what the lumbermen have left of a hackmatack swamp at their foot, looking for a way about the bottom stair, for only Baron Munchausen's courier—he of the seven-league boots—could have gone directly up it. It felt like being a mouse in a mansion, and by and by I found a very mouse-like route up detached boulders loosely held in place by spruce roots, scrambling up trunks and clawing on with fingers and toes, in momentary fear of starting an avalanche and becoming but a very small integral portion of it, and I finally reached the top of the bottom back stair, which is by all odds the highest, and sat down to get breath. At one scramble I had left behind the woful tangle of slash and come into a country of enchantment. Here a bear had passed the day before, leaving undeniable signs. There was a deer path through the dense spruce showing recent dents of their sharp, cloven hoofs, and all about and above was a forest of black growth, in which it was easy to fancy no human foot had ever trod, before I all-foured up into it, mouse fashion. Here were trees not large enough to tempt the lumbermen, but old with moss and gray-green lichens, casting so dense a shade that only mosses and lichens could flourish beneath them.

Here was a soft carpet of dainty cedar moss, wonderfully fronded and luxuriant, covering everything,—rocks, roots and the trunks of ancient trees that had fallen one across another for unnumbered centuries. It was like a miniature of the close-set tangle of downwood and growing timber that one sees in the Puget Sound country. There for miles one may make progress through the wood only by clambering along one fallen trunk to the next, perhaps twenty feet in air. Here the fallen trunks and growing trees were not one-tenth the size of the Pacific coast giants, but the proportion and condition was the same. And so up through this fairyland I scrambled and plunged, following a deer path as best I might and longing for their sure-footed ability to leap lightly over obstacles. I daresay my clattering plunges drove all the deer off the mountain. At least I saw none, though their paths intersected and their hoof-marks had dented them all recently. Stairs Mountain is certainly the house of a thousand staircases. All through my climb I found detached stairs scattered about, and the mountain seems to be largely built of them, from a few feet to a few hundred feet in height.

And after all I came out, not at the top of the highest front stair, but at the top of that side stair that looks directly down on the old lumber camp. A half mile or less southeast of me were the front stairs, and I had to go down an internal flight and climb again before reaching their top, passing again through forest primeval criss-crossed by deer paths. The yellow-headed woodpecker had given me a pretty scramble, but I think it was worth it.

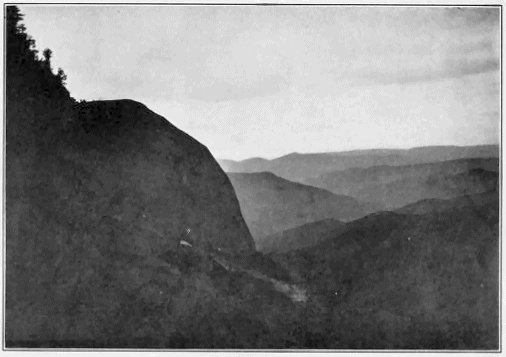

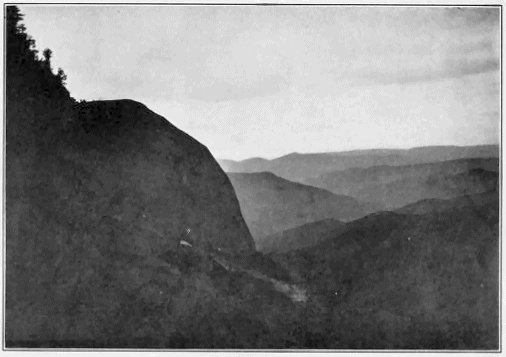

"From the top tread of the Giant's Stairs one sees half of the mountain world, the half to southward"

From a distance I had thought Stairs Mountain to be fractured slate. Instead it is moulded granite. The edge of the tread on the topmost stair is of a stone that seems as hard and dense as any that comes out of the Quincy quarries. Yet still clinging to it in places are remnants of a crumbly granite that seems once to have been poured over it and cooled there in a friable mass. You may kick this overlying granite to pieces with your hob-nailed mountain shoe, and I fancy once it filled the gap between the topmost tread and the summit of Mount Resolution, just to the south, and has been frost riddled and water worn away leaving the solid granite of the stairs behind.

From the topmost of the Giant's Stairs one sees but half the mountain world,—the half to southward. All the north is cut off by the spruce-covered round of the summit behind him. Eastward was the great bulk of Iron Mountain, over which I had come, its round top so far below me that I could see the whole of the perfect cone of Kearsarge over it. Directly south was the half bald dome of Resolution, and just over it the equilateral pyramid of Chocorua dented the sky. Wonderfully blue and far away it looked, and to its right was stretched the varied sky-line of the whole Sandwich Range. To the right again was a mighty wilderness of mountains, cones and billows and ranges massed in together in almost inextricable confusion, though out of this rose certain peaks one could not fail to recognize,—Carrigain, stately and a bit apart in dignified reserve, and the great blue wall of the Franconia Range, diminished by distance but beautiful and impressive still. Almost at my feet, down the Crawford Notch, crept a train along the thin, straight line of the railroad. A puff of white steam shot upward from the engine whistling for the Frankenstein trestle, but it was long before the shrill sound rose to my ears. Nothing could so well emphasize the immensity of the prospect before me. I realized that the brakeman was walking through the observation car shouting, "Giant's Stairs! Giant's Stairs now on your left!" and that the mighty cliff on whose verge I was perched seemed no more than a letter on the printed page to the onlooking crowd.

The way home lies down the west side of the mountain, the steep but good Davis trail to and along the bottom of the lower stair, thence to the west side of the ridge between Stairs Mountain and Mount Resolution. Then a trail east, very slender but distinguishable, goes to the broad highway of a logging road, and thence the descent, though precipitous, is easy. The Stairs Mountain is so different from anything else that one can find in this region that it has an eerie individuality all its own. To look back as I went on down the logging road was to see the stairs standing out against the glow of the lowering sun, less like steps than gigantic rock faces. The lower one particularly looked as if a giant himself, wild-eyed and bristly haired, was lying behind the forest with his great head leaned against the mighty granite cliff that towered above. And so I left him, waiting doubtless to devour the next lone climber who, if he goes up the front stairs, must pass directly in front of his jaws. For all that I hesitate to advise the back stairs route to which the yellow-headed woodpecker led me. It is rough—and chancey.