I

UP CHOCORUA

The Mountain and Its Surroundings in Mid-May

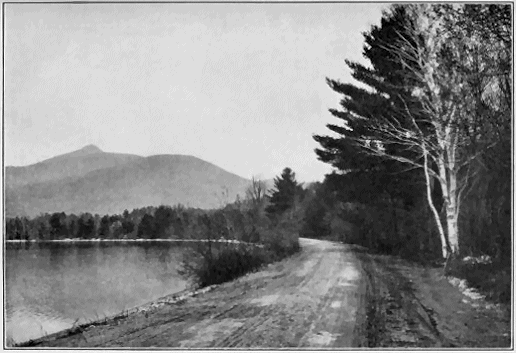

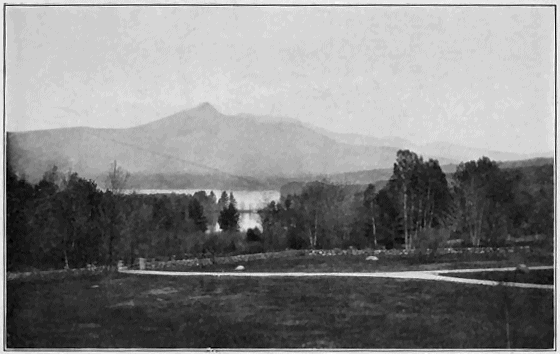

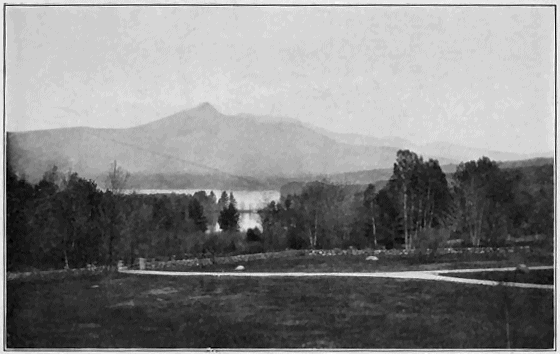

The smooth highway over which thousands of automobiles skim in long summer processions from Massachusetts to the mountains, coquettes with Chocorua as it winds through the Ossipees. Sometimes it tosses you over a ridge whence the blue bulk and gray pinnacle stand bewitchingly revealed for a second only to be eclipsed in another second by the lesser, nearby beauties of the hill country, and leave you wistful. Sometimes it gives you tantalizing flashes of it through trees or by the gable of a farm-house on a round, hayfield hill, but it is only as you glide down the long incline to the shores of Chocorua Lake that the miracle of revelation is complete. Then indeed you must set your foot hard on the brake and gaze long over the Scudder farm-house gate down a green slope of field to the little lake, and as the eye touches approvingly Mark Robertson's rustic bridge, set in just the right spot to give the human touch to the wild beauty of the landscape, and leaps beyond to the larger lake framed in its setting of dark growth, and on again to the noble lift of the great mountain with its bare pinnacle of gray granite, you realize the grandeur and beauty of this outpost sentinel of the white hills. It is hard to believe that Switzerland or Italy or any other country has anything finer than this to show the traveller.

"The smooth highway over which thousands of automobiles skim in long summer processions from Massachusetts to the Mountains"

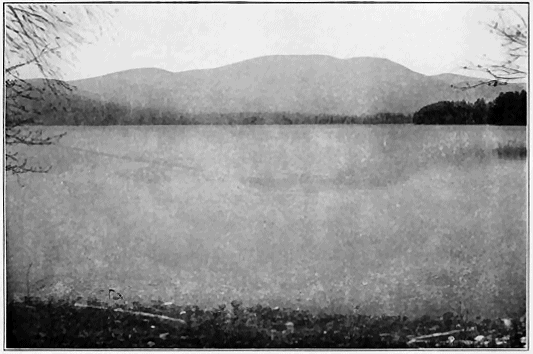

It was a wonder day in May when I first stopped, spell-bound, upon this spot. A soft blue haze of spring was over all the mountain world, making mystery of all distant objects and lifting and withdrawing the peak into the sky of which it seemed but a part, only a little less magical and intangible. Hardly was this a real world on this day, but rather one painted by some mighty master out of semi-transparent dust of gems. The lake was a mirror of emerald stippled about its distant border with the chrysophrase reflection of young leaves, carrying deep in its heart another, more magical, Chocorua of softest sapphire tapering to a nadir-pointing peak of beryl. Out of the nearby woods came the song of the white-throated sparrow, the very spirit of the mountains, a song like them, built of gems that fade from the ear into a trembling mist of sound, the nearby notes sapphire peaks, the others distant and more distant till they seem but the recollection of a dream. Such days come to the mountains in May and they bring the white-throats up with them from the haze of the subtropics where they are born.

If one would climb Chocorua by the Hammond trail he must leave the smooth road that winds onward to Crawford Notch after he passes Chocorua Lake. There another, less smooth but still available to carriage or motor, will take him across Chocorua Brook and end at a house in the woods. Just before the end it crosses a second brook, and there is the beginning of the trail, a slender footpath only, but well defined in the earth and well marked by little piles of stone wherever it goes over ledges. It is hardly possible to miss it in daylight; after dark it would be hardly possible to find it. Twice it crosses the brook, the second time leaving it to gurgle contentedly on in its ravine and rising more directly skyward. Beech and birch branches shimmered overhead with the translucent green of half-grown young leaves along the lower reaches of this trail. Maples flushed the green in spots with tapestry of coral red. Scattered evergreens, pine, spruce, hemlock and fir lent backgrounds of green that was black in contrast to the lighter tints. Smilacina, checkerberry and partridge berry wove carpets of varying color in the tan brown of last year's leaves, climbing the slope as bravely as anyone, and painted and purple trilliums did their best to follow, but had not the courage to go very far. The pipsissewa, bellwort and Solomon's seal did better. A few of them dared the ledges well up to the top of the first great southerly spur which the trail ascends.

It was the day after I had first seen Chocorua and a wind out of the west had blown the blue haze of unreality away from the mountain, massing it to the east and south where it still held the land in thrall. I got the blue of it through straight stems of beech and birch and through the soft quivering of their young leaves painted with the delicate coral tracery of maple fruit.

All the way up the lower slope one is drowned in Corot. I watch yellow-bellied sap-suckers make love among the beeches, the crimson of their crowns and throats flashing with ruby fire, the blotched gray and white of wings and bodies a living emanation of the bark to which they cling. Their colors seem the impersonal fires of the young trees personified. In this, another wonder day of May, the goodness of God to the green earth flows in a tide of unnameable colors up the mountain-side, enflaming bird and tree alike and from the great shoulder of the mountain I look down through its mist of mystery and delight to Chocorua Lake, a clear eye of the earth, wide with joy and showing within its emerald iris as within a crystal lens magic mountains, upside down, and between their peaks the turquoise gateway to another heaven, infinitely deep below. The lowland forest sleeps green at my feet, a green of sea shoals that deepen into the tossing blue of mountains far to the south, Ossipee, Whittier, Bear Camp and the lesser hills of the Sandwich range.

Many of the shrubs and trees of the lower slopes climb well to the top of this great southerly spur of the mountain, but straggle as they climb and lessen in number as they reach the height. Few of the lowland birds get so far, but among the dense spruces and firs which crowd one another wherever there is soil for their roots among the weather worn ledges, deciduous trees sprinkle a green lace of spring color, and among the spruces, too, is to be heard the flip of bird wings and an occasional song. Here the hardier denizens of the country farther to the north find a congenial climate. Myrtle warblers show their patches of yellow as they flit about, feeding, making love and selecting nest sites, and with them the slate-colored juncos glisten in their very best clothes and show the flesh color of their strong conical bills. These two are birds of the mountain and they climb wherever the spruce does.

Beyond the crest of this great southerly spur the path dips through ravines and climbs juts of crag and débris of crumbled granite to the base of the great cone which is the pinnacle. Now and then one gets a level bit for the saving of his breath and his aching leg muscles and may find a seat on fantastically strewn boulders, dropped by the glaciers when they fled from the warmth to come. On up the mountain go the small things of earth, too. Here are sheep laurel and mountain blueberries, stockily defiant of the winter's zero gales, the laurel clinging as firmly to its last year's leaves as it does on the sunny pastures of the sea level hundreds of miles to the south, the roots set in the coarse sand that the frost of centuries has crumbled from rotten red granite. Poplars climb among the spruces and willows are there, their Aaron's rods yellow with catkins in the summer-like heat that quivers in the thin air. The trees feel in them the call to the summit as does man.

As they go on you seem to see this eagerness to ascend expressed in the attitudes of the trees themselves. To the southwest a regiment of birches has charged upward toward the base of the pinnacle. Boldly they have swarmed up the steep slope and, though the smooth acclivities of the ledges about the base of the cone have stopped all but a corporal's guard, and though they stand, theirs is the very picture of a turbulent, onrushing crowd. Motionless as they are, they seem to sway and toss with all the restless enthusiasm of a mighty purpose; nor could a painter, depicting a battle charge, place upon canvas a more vivid semblance of a wild rush onward toward a bristling, defiant height. Few are the birches that have passed this glacis of granite that forever holds back the body of the regiment, yet a few climb on and get very near the summit of the gray peak. More of the dwarf spruces have done so. In compact, swaying lines they rush up, marking the wind and spread of slender defiles and leaning with such eagerness toward the summit that you clearly see them climbing, though they are individually motionless, rooted where they stand. There is a black silence of determination about these spruces that must indeed carry them to the highest possible points, and it does, while to the eye the birches behind them toss their limbs frantically and cheer.

"You realize the grandness and beauty of this outpost sentinel of the White Hills"

Whether the little blue spring butterflies climb the mountain or whether they live there, each in his chosen neighborhood, going not far either up or down, it is difficult to say, but I found them in many places along the trail to the base of the cone, little thumbnail bits of a livelier, lovelier blue than either the sky or the distant peaks could show, frail as the petals of the bird-cherry blossoms that fluttered with them along the borders of the path, yet happy and fearless in the sun. With them in many places I saw the broad, seal-brown wings of mourning cloaks, and once a Compton tortoise flipped from the path before me and hurried on, upward toward the summit. I looked in vain for him there, but as proof that butterflies do climb to the very top of Chocorua I saw, as I rested on the square table of granite which crowns it, a mourning cloak, which soared up and circled me as I sat, rose fifty feet above, then coasted the air down toward the place where the birches seemed to toss and cheer in the noonday sun. He had won the height, and more, and I envied him the nonchalant ease with which his slanting planes took the descent.

One other creature I saw, higher yet, a broad-winged hawk that swung mighty circles up from the ravine to the southeast, down which one looks in dizzy exaltation from the very summit. There was a climber that outdid all the rest of us in the swift ease of his ascent. Out of nothing he was borne to my sight, a mote in the clear depths three thousand feet below, a mote that swept in wide spirals grandly up with never a quiver of the wing. Up and up he came till he swung near at the level of my eye, then swirled on and on, a thousand feet above me. A moment he poised there, then with a single slant of motionless wings turned and slid down the air mile on mile, one grand, unswerving coast, to vanish in the blue distance toward Lake Ossipee.

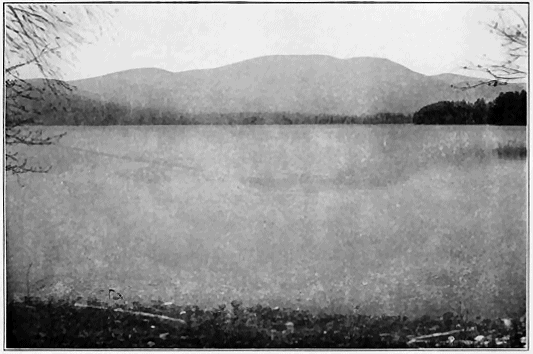

Southerly from Chocorua summit the land was soused in the steam of spring. Chocorua Lake lay green at my feet, an emerald mirror of the world around it. To its right a little way Lonely Lake was a dark funnel in the forest, a shadowy crater opening to unknown depths in the earth below, filled with black water, and all to the east and south the country lay flat as a map, colored in light green, the lakes in dark green or steel blue, the roads in dust brown, the villages scattered white dots, while beyond a blue mist of mountains was painted on the margin for the horizon's edge.

To look north and west was to look into another world, to realize for what mountains Chocorua stands as the sentinel at the southeast gate. Paugus lifted, a blue-black, toppling wave to westward, seemingly near enough to fall upon Chocorua summit, while over its shoulder peered Passaconaway flanked with Tripyramid and White Face. Northward and westward from these toppled the pinnacles of jumbled, blue-black waves of land that passed beyond the power of vision. Northward again the glance touched summit after summit of this dark sea of mountains till the crests lifted and broke in the white foam of the Presidential Range with Mount Washington towering, glittering and glacial, above them all. Here was no steam of spring to soften the outlines and blur the distance in blue. Rather the crystal clearness of the winter air still lingered there, and though but a few drifts of December's snow lay on Chocorua and none were to be seen on the other, nearer mountains, Carrigain was white crested and Washington topped the ermine of the Presidential range like a magical iceberg floating majestically on a sea of driven foam. Chocorua is not a very high mountain. Three thousand feet it springs suddenly into the blue from the lake at its feet, 3508 feet is its height above the sea level, but its splendid isolation and the sharpness of its pinnacle give one on its summit a sense of height and of exaltation far greater than that to be obtained from many a summit that is in reality far higher.

Yet to him who stays long on the summit of Chocorua thus early in the spring is apt to come a certain sense of sadness, following the exaltation of spirits, sadness for the inevitable passing of this inspiring pinnacle. The work of alternating heat and cold, of sun and rain, are everywhere visible, beating the granite dome to flinders and carrying it down into the valley below. The bare granite shows the sledgehammer blows of the frost as if a giant had been at work on it making repoussé work with the weapon of Thor. Not a square foot of the sky-facing ledges but has felt the welts of this hammer of the frost, each lifting a flake of the stone, from the size of one's thumbnail to that of a broad palm. These crumble into nodules of angular granite that make drifts of coarse sand even on the very summit. The sweep of the wind and the rush of the rain come and send these in streams down the mountain side. The rain and the water of melted snow do another work of destruction, also. Such water has a strong solvent power, even on the grim granite. Always after rain or during the snow-melting season of early spring, there is a little basin full of this water in the bare rock just northeast of the very summit. There it stands till the winds blow it away or the thirsty sun dries it up, and year after year it has dissolved a little of the rock on which it rests till it has worn quite a basin in the granite,—a basin which looks singularly as if it had been hollowed roughly out by mallet and chisel. So the work goes on, and Chocorua summit is appreciably lowered, century by century.

Fortunately man thinks in years and not in geological epochs, else the sadness of the thought were more poignant. After all, the work of erosion of the centuries to come can never be so great on the mountain as that of the centuries that have passed, for the geologists tell us that all the summits of the Appalachians were once but valleys in the vast table-land which towered far higher above them than they now do above the sea. The forces of erosion whose patient work one now sees on Chocorua summit have hammered at the hills thus long. So wears the world away, but the great square block which sits on the very peak of the mountain shows none of the bruises which fleck the soft granite below it, and it may well be many a thousand years before it slides down into the ravine below.

The black bulks of Paugus and the mountains beyond were rimmed with the crimson fire of the westering sun as I reluctantly climbed down from the peak of this hill of enchantment, greeted by the evensongs of the juncos and myrtle warblers in the first broad patches of spruce about the base of the cone. A pigeon hawk swung up from the westerly ravine and hovered a moment so near me that I could see the white tip of his tail and the rusty neck collar, then slid down the air and vanished in the ravine on the opposite side of the mountain. He builds his nest on mountains and was well fitted to show me the easiest way down. I grudged him his wings as I waked the yelps in a new set of leg muscles, slumping down the slopes and climbing laboriously down the almost perpendicular, rocky ravines. The Hammond trail is no primrose path, for all its beauties, and it was my first climb of the year. I was glad indeed to drink deep of the mountain brook near the end of the trail and then rest a bit to the soothing contralto of its song.

The shadowy coolness of the evening was welling up and blotting the gold of sunset from the treetops as I rounded Chocorua Lake and watched the sunset fire the summit where I had lingered so long,—a fire reflected deep in the very heart of the mirroring waters. The roar of the little river on its way down to Chocorua town came faintly to me, a sleepy song, half that of the wind in pines, half an echo of droning bees that work all day in the willow blooms by its side. Liquid, clear, through this came the songs of wood thrushes out of the shadows. The peace of God was tenderly wrapping all the world in night, and the mountain loomed farther and farther away in blue mystery and dignity, while from its pinnacle slowly faded the rosy glow of the passing, perfect day.

"The shadowy coolness of evening was welling up and blotting the gold of sunset from the treetops”