II

BOBOLINK MEADOWS

Early June about Jackson Falls and Thorn Mountain

On a May morning after rain the bobolinks came to the meadows up under the shadow of Thorn Mountain. The morning stars had sung together and the breaking of day let tinkling fragments of their music through, or so it seemed. Something of the sleighbell melodies that have jingled over New Hampshire hills all winter was in this music, something of the happy laughter of sweet-voiced children, and something more that might be an echo of harps touched in holy heights. Surely it is good to be in the mountains at dawn in May, when such sweet tinklings of melody fall out of celestial spaces! The high hills were veiled in the mists of the storm that had passed, but the nearer summit of Thorn leaned friendly out of them, and over it from the south pitched the fragments of heavenly music, fluttering down on short wings like those of cherubs. The bobolinks had come to Jackson.

It is as easy to believe that the cherubs of Raphael and Rubens can make the journey from high heaven to earth on their chubby wings as that these short-winged, slow-fluttering birds can have come from the marshes below the Amazon on theirs, but so they have done, finding their music on the way. They went south in early September, brown, inconspicuous seed-eaters with never a note save a metallic "chink." Somewhere in the far south they found new plumage of black with plumes of white and old gold. Somewhere in the sapphire heights of air above the Caribbean Sea they caught the tinkling music of the spheres and dropped upon Florida with it in the very last days of April, bringing it thence again in joyous flight that drops them among the mountain meadows in mid May.

Now June is making the grass long about the little brown nests where the brown mother-bird sits so close, but the meadows are full of tinkling echoes of celestial music still. All the mountain world is rapturous with this same joy of something more than life which the bobolinks brought from on high in their songs, dancing and singing with it and tossing something of beauty skyward day and night. Round the margins of the bobolink meadows the apple trees have completed their adoration of bloom, the strewing of incense and purity of white petals down the wind, and now yearn skyward with tenderness of young leaves. The meadow violets smile bravely blue from shy nooks, and the snow that lingered so long on the slopes is born again in the gentler white of houstonias which frost the short grasses with star-dust bloom. All the heat of the dandelion suns that blaze in fiery constellations round the margins cannot melt away this lace-work of the houstonias, and it is not till the buttercups come, too, and focus the sun rays from their glazed petals of gold that the last frost of the season, that of the houstonia blooms, is melted away. Dearly as the bobolink loves his brown mate in the nest, the moist maze beneath the grass culms where he dines, and his swaying perch on the ferns that feather the meadow's edge, he, too, feels this upward impulse within him too strong to resist and continually flutters skyward, quivering with the joy of June and setting the air from hill to hill a-bubble with his song.

The bobolink meadows begin on the grassy levels between the Ellis and Wildcat rivers, the bottom land which forms the foothold of Jackson town, and they climb the mountains in all directions as do the summer visitors, scattering laughter and beauty as they go, till you hear the tinkle of the bobolink's song and find the beauty of meadow blooms in tiny nooks well up toward the very summits. Up here the shyest meadow birds and sweetest meadow flowers seem to love the rough rocks well and climb them by the route that the brooks take as they prattle down from the high springs. Up the very rivers they troop, and though they turn aside eagerly to the safer haven of the brook sides, they climb as well by way of the boulders that breast the roar of the bigger streams. The Wildcat River plunges right down into Jackson village by way of Jackson Falls, a thousand-foot slope over granite ledges worn smooth with flood, and mighty boulders scattered in bewildering confusion. In time of freshet this long incline is a welter of uproarious foam. This year a long spring drought has bared the rocks in many places, and one may climb the length of the falls as the stream comes down, from ledge to ledge and from boulder to boulder.

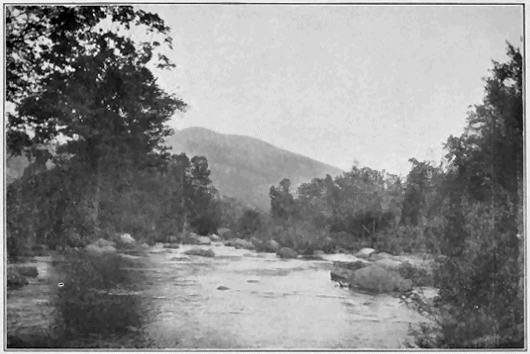

The Glen Ellis River at Jackson, New Hampshire, Thorn Mountain in the distance

The rush of the water drowns the warbling of the water-thrushes in the alders and viburnums on the banks, it drowns the cool melodies that the wood thrushes sing from the deep shade of the wooded slopes along the stream, but nothing has drowned the wild flowers that climb the falls by way of the ledges and boulders as the adventurous fisherman does. Why the whelming rush of freshets has not wiped them out of existence it is hard to say. There must be times each year when they are buried deep beneath the boiling foam, but there they cling this June and smile up in the sun and take the fresh scent of the churning waters as a strong basis for their perfumes. They knew the tricks of the perfumer's trade long before there were perfumers, and the moisture of the flood itself is their ambergris. Here the cranberry tree leans over the water and drops the white petals of the neutral blooms from its broad, flat cymes to go over one fall after another on their way to Ellis River and, later, the Saco. The gentle meadow-sweet dares far more than this. It grows from slender cracks in the face of perpendicular granite, and with but rocks and water for its roots thrives and bathes its serrate leaves in the spray. The mountain blueberries have set their feet in similar places and hang fascicles of white bells over the water for the more daring of the bumblebees that have their nests in the moss of the river banks.

Showiest and boldest of all is the rhodora which has taken possession of a rock island in midstream well up the falls. Here in a tangle of rock points and driftwood it grows in clumps and puts out its umbel clusters of richest rose, a mist of petals that seems to have caught and held one of the rainbow tints from the spray that dashes by the blooms on either side. Nor is even this, with its showy beauty that Emerson loved, the loveliest thing to be found growing out of granite in the very tumult of the waters. The blue violet is there, unseen from the bank but smiling shyly up to him who will clamber out to midstream, finding coigns of vantage down where even at low water the splash of spray sprinkles its pointed leaves and violet-blue flowers. Viola cucullata is common to all moist meadows and stream margins from Canada to the South, but nowhere does it bloom more cheerily and confidingly than in the midst of the rush and roar of Jackson Falls in these danger spots among the rocks. One clump I found in a square well of granite in the very wildest uproar, holding its sprays of bloom bravely up in a spot that at every freshet must be fairly whelmed with volumes of whirling icy water. How it holds this place at such times only the clinging, fibrous roots and the gray granite that they embrace can tell, but there it is, blooming as sweetly and contentedly as in any sheltered, grassy meadow in all the land.

Up from the bridge above Jackson Falls the road climbs by one bobolink meadow after another along the slope of Tin Mountain till it stops at the wide clearing on the higher shoulder of Thorn, which was once the Gerrish farm. Farm it is no longer, for the farmers are long gone. The jaw-post of the old well-sweep leans decrepitly over the well, which is choked with rubbish. The weight of winter snow and the rush of summer rain have long since broken through the roof of the old house and are steadily carrying it down into the earth from which it sprang. The chimney swifts have deserted the crumbled chimney, and the barn swallows no longer nest in the barn, last signs of the passing of a homestead, and even the phœbes have gone to newer habitations, but the broad acres are still strong in fertility and the grass grows lush and green on the gentle slopes. Down from Thorn summit and over from Tin the forest advances, but hesitatingly. It is as if it still had memory of the strokes of the pioneer's axe and did not yet dare an invasion of the land he marked off. It sends out skirmishers, plumed young knights of spruce and fir, scouts of white birch and yellow, of maple and beech, to spy out the land, and where these have found no enemy it is advancing, meaning to take peaceful possession, no doubt, for the wild cherries and berry bushes mingle with the old apple trees, and both hold out white blossom flags of truce.

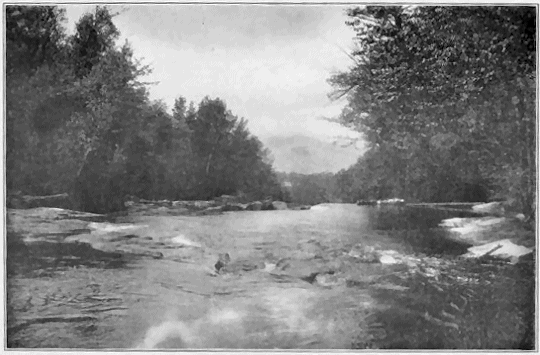

Down the Wildcat River, over the brink of Jackson Falls, Moat Mountain in the distance

One wonders if the pioneer did not have an eye for mountain scenery as well as for strong, rich land, for from the very doorstone of the old house the glance sweeps a quarter of the horizon, scores of miles from one blue peak to another. At one's feet lies Jackson as if in a well among the hills, Eagle Mountain and Spruce and the ridges beyond dividing the valley of the Wildcat from the glen of Ellis River, yet not rising high enough to hide the peak of Wildcat Mountain, up between Carter and Pinkham notches. Iron Mountain rises on the left of Jackson, and beyond it the unnamed peaks of Rocky Branch Ridge lead the eye on to the snow still white in the ravines of the Presidential Range and Mount Washington looming in serene dignity to the northwest. One may climb thus far on Thorn Mountain by carriage if he will, or by motor car indeed, provided he has a good hill climber. The ascent is often made thus. But to get to the very summit, the point of the thorn, a footpath way leads up through the bars into the pioneer's pasture, onward and upward through the forest.

The pasture ferns climb too, and the pasture birds love the wooded summit as well as they do the slopes far below the pioneer's farm. The June delight which echoes in the bobolink music in the meadows so far below sweeps up the mountain-side in scent and song and color till it blossoms from the Puritan spruces on the very top of Thorn. There one glimpses the rare outpouring of joy that comes from reticent natures. They are in love, these prim black spruces, and they cannot wholly hide it however hard they try. Instead they tremble into bloom at the twig tips, and what were brown and sombre buds become nodding blossoms of gold that thrill to the fondling of wind and sun and scatter incense of yellow pollen all down the mountain-side. In the distance they are prim and black-robed still, but to go among them is to see that they wear this yellow pollen robe in honor of June, a shimmering transparent silk of palest cloth of gold. More than that, their highest plumes blush into pink shells of acceptance of joy, pistillate blooms of translucent rose as dear and wondrous in their colors of dawn as any shells born of crystalline tides, in tropic seas, blossoms whose fulfilment shall be prim brown cones, but each of which is now a fairy Venus, born of the golden foam of June joy which mantles the slender trees. Only with the coming of June to the mountains can one believe this of the spruces, because seeing it he knows it true.

The little god of love has shot his arrow to the hearts of the trembling spruces, and he sings among their branches in many forms. The blackburnian warbler lisps his high-pitched "zwee-zwee-zwee-se-ee-ee" all up the slope of Thorn to the summit and shows his orange throat and breast in vivid color among the dark leaves. The black-throated green, moving nervously about with a black stock over his white waistcoat, sings his six little notes, and the magnolia warbles hurriedly and excitedly his short, rapidly uttered song. The mourning warbler imitates the water-thrush of the misty banks of Jackson Falls, and the Connecticut warbler echoes in some measure the "witchery, witchery" of the Maryland yellow-throats, both birds that have elected to stay behind with the bobolinks.

Thus carolled through cool shadows where the striped moosewood hangs its slender racemes of green blossoms, you come rather suddenly out on the bare ledges which face northerly from the summit. Truly to see the mountains best one should look at the big ones from the little ones. Here is the same view that Gerrish had from his farm, only that you have a wider sweep of horizon. Over the Rocky Branch Ridge to the westward rises the Montalban Range, with the sun swinging low toward Parker and Resolution and getting ready to climb down the Giant's Stairs and vanish behind Jackson and Webster. Everywhere peak answers to peak, and you look over low banks of mist that float upward from unknown glens, forming level clouds on which the summits seem to sit enthroned like deities of a pagan world. There is little of the bleak débris of battle with wind and cold on the summit of Thorn. It is but 2265 feet above sea level, lower than most of the mountains about it, and the trees that climb to its top and shut off the view to the east and south are in no wise dwarfed by the struggle to maintain themselves there. But from it one gets a far better outlook on mountain grandeur than from many a greater height. Washington holds the centre of the stage which one here views from a balcony seat, seeming to rise in splendid dignity from the glen down which the Ellis River flows, and it is no wonder that there is a well-worn path from the Gerrish farm to the point of the Thorn.

It may be that the pioneer who first hewed the mountain farm from the forest also first trod this path to the very summit of the little mountain. It may be that he got a wide enough sweep of the great hills on the horizon to the north and west from his own doorstone. But I like to think that once in a while, of a Sunday afternoon perhaps, he went to the peak and dreamed dreams of greater empire and higher aspirations even than his mountain farm held for him. There is a tonic in the air and an inspiration in the outlook from these summits that should make great and good men of us all. These linger long in the memory after the climb. But longer perhaps even than the hopes the summit gives will linger in the memory of him who climbs Thorn Mountain in early June the recollection of two things, one at least not of the summit. The first is the joy of June in the bobolink meadows far down toward Jackson Falls, the celestial melodies that the bobolinks echo as they flutter upward in the vivid sunshine and sing again to mingle their white and gold with that of the flowers that bloom the meadow through. The other is the bewildering beauty of the once black and sombre spruces in their sudden draperies of golden staminate bloom, looped and crowned with the pistillate shells which so soon will be prim brown cones. The bobolinks will sing in the meadows for many weeks. The mountains will blossom with one color after another till late September brings the miracle of autumn leaves to set vast ranges aflame from glen to summit, but only for a little time are the spruces so filled with the full tide of happiness that they put on their veils of diaphanous gold and their rosy ornaments of new-born cones. It is worth a trip into the hills and a long climb to see these at their best, which is when the bobolinks have eggs in the brown nests in the meadow grass and the blue violets are smiling up from the rock crevices in the midst of the tumult of Jackson Falls.