CHAPTER VII

ALFRED’S DEATH AND SIXTY YEARS AFTER

Erunt reges nutritii tui, et reginae nutrices tuae.

WHEN Alfred died in 901 he had accomplished a great work; a work great and lasting, as the next sixty years were to show, and during these years the ascendancy of Wessex and of the line of Egbert was to grow more and more undisputed, till it culminated in the reign of Edgar the Magnificent. These days were days of rapid development in Winchester, and the fortunes of the city at this period were closely linked with Alswitha, Alfred’s widow, Grimbald, the monk, and the two strong kings of Alfred’s line, Edward, his son, and Athelstan, his grandson.

As already related, Alfred had planned the important foundation of the Newan Mynstre, and had settled the site before his death. Its completion was the work of the early days of Edward the Elder, who, almost immediately on ascending the throne, convened a great meeting of the Witan at Winchester to discuss the matter at the outset. The king’s own views were limited and parsimonious, and he was anxious to lay the lands of the Ealden Mynstre under contribution as a means of defraying the cost, but the venerable Grimbald, now over eighty years of age, was inflexible. “God will not,” said he, “accept robbery for burnt-offering,” and he carried his point. The king made a liberal endowment for the purpose, and the walls of the minster rose apace. At the same time the abbey of St. Mary, founded by Alswitha, was proceeded with, and the monastic quarter of the city saw a trinity of fair monasteries, grouped side by side, rise rapidly into prominence. Accident served to invest the new abbey with peculiar interest and sanctity. A Danish descent on Picardy had driven a crowd of refugees to seek shelter across the sea, and they had crossed over to Hampshire, bearing with them their greatest treasure—the hallowed bones of their patron saint, St. Judocus or St. Josse. The king received them hospitably at Winchester, and the sacred relics were solemnly and splendidly enshrined within the partially completed church of the New Minster. Then in 903, in the presence of a great concourse of nobles and clergy, the dedication of the New Minster was solemnly performed by Plegmund, Archbishop of Canterbury. Scarcely was this completed ere another equally striking act was performed, viz. the translation within the walls of the new church of the remains of the founder, the great Alfred himself—a solemn and imposing rite, carried out with all the pomp and dignity of impressive circumstance:

cum apparatibus regali magnificentia dignis

(with solemn pomp befitting his royal state),

as the Liber de Hyda informs us.

Then in rapid succession Grimbald, Alfred’s first nominated abbot, and Alswitha, his devoted queen and widow, were called to rest, and the queen’s remains were piously interred side by side with those of her husband. Thus within three years of Alfred’s death the Newan Mynstre had risen not merely into being, but had already become invested with ascendancy and popular prestige as the hallowed repository of the mortal remains of a wonder-working saint, a venerated abbot, of a saintly king, and of his royal consort. Some twenty years later, within the same abbey church—thus already established as a venerated mausoleum—Edward the Elder himself was also laid, after a strenuous reign, in which he had consolidated the Anglo-Saxon power and had re-established firmly the unity of the kingdom. Thus, as year succeeded year, Winchester grew in extent and importance. The prestige and dignity of its ecclesiastical foundations established it thus early as the leading centre of pious pilgrimage in the south of England, and shopmen and merchants followed eagerly the pilgrim stream. Accordingly Edward the Elder drew up what may be called the first commercial code of the city—laws regulating the selling of goods and the making of bargains in open market in the city. In the same reign associations or confraternities of traders for mutual support began to be formed—confraternities which, under the name of ‘gilds’ or guilds, were destined to become in time corporate municipal bodies, with the ‘Hall of the Gild Merchant’ as the centre of civic rule and influence. A formal mayor and corporation were to come later, but the elements and something more of civic rule in Winchester can be thus traced continuously back and recognized for full a thousand years.

Of Athelstan the warrior we have but little actual Winchester history to record; he reigned from 925 to 940, and was buried not at Winchester but at Malmesbury. To atone for this historical paucity we have one glorious romantic legend—the legend of the fight between Guy of Warwick and Colbrand, the Danish giant and warrior, a story which has long been a classic fairy tale. Rudborne, in his Major Historia Wintoniae, copying from the Liber de Hyda, solemnly records how Athelstan, invested in his capital city by Anelafe, King of the Danes, agreed with his besieger to decide the issue by a combat between champions, and he tells us how a new Polyphemus,

monstrum, horrendum, informe, ingens,

Colbrand, “a giant wondrous of stature, hideous of aspect, and of unparalleled ferocity,” came forward to champion the Danish cause, and how the English protagonist, Guy of Warwick, his opposite in every attribute, “prudent, self-restrained, resolute, manly in mind and skilled to combat,”

Against great odds bare up the war

“in a certain meadow lying northward of the city, now called De Hyde mead, then called Denemarck,” while Athelstan watched the combat anxiously from a corner of the city walls. Swords flashed, splinters flew, long was the conflict doubtful; each antagonist in turn prevailed, while hearts beat fast and lips grew white with tense compression, till right prevailed, and the head of the second Goliath was severed from its trunk by our Saxon David.

The worthy Knighton, in his De Eventibus Angliae, amplifies the story, and the details fairly scintillate at his imaginative smithy. The fight occurs in Chiltecumbe or Chilcomb valley; Guy of Warwick takes the field, mounted on Athelstan’s own steed and girt with arms of wondrous potency—the sword of Constantine the Great, the spear of Saint Maurice himself.

Colbrand, also mounted, bears with him a whole armoury—axe, and club, and iron hook—while a waggon by his side bears a whole assortment of miscellaneous ironmongery for him to use at need against his adversary. It is strength, and stature, and brute force against courage and address, and for a long time Guy appears to be at the mercy of his adversary. The latter, however, in dealing a ponderous blow—the coup de grâce as he imagines—contrives to let his weapon slip, and as he reaches to recover it, the English champion rushes in and severs his hand from off his arm. Nevertheless, the issue is for long in doubt, and it is not till darkness has all but fallen that the giant’s strength ebbs from weakness and loss of blood, and his nimble adversary shears off his head with one sweep of his sword. Readers of Kingsley’s Hereward the Wake will recall in the above act something more than a reminiscence of the strong conflict between Hereward and Ironhook, the Cornish giant. The story is indeed a Cornish legend, localised round Athelstan and the Wessex capital. Gerald of Cornwall, a writer whose writings exist now only in fragments, related it in his De Gestis Regum Westsaxonum, and it is his account, incorporated in the Liber de Hyda, which is the source of its introduction into our local history. Yet strange as it may seem, this wildly impossible romance was accepted for centuries as historical; Danemark mead still exists as a local name, and an inn known as the Champions only disappeared from the reputed locale of this wonderful conflict a few years ago.

And so through legend and historical record alike, our city’s history moved forward step by step. King after king of Egbert’s line succeeded to the throne and ruled in Winchester. Edred the Pious succeeded Edmund the Magnificent and was buried in the Old Minster. Edwy the Inglorious succeeded Edred, and died and was buried in the New Minster, and thus in 959 the realm passed under the rule of Edgar, his half-brother, Edgar the Peaceable, whom the monks named also Edgar the Magnificent. With his reign a fresh chapter of interest and importance opens in our city’s history.

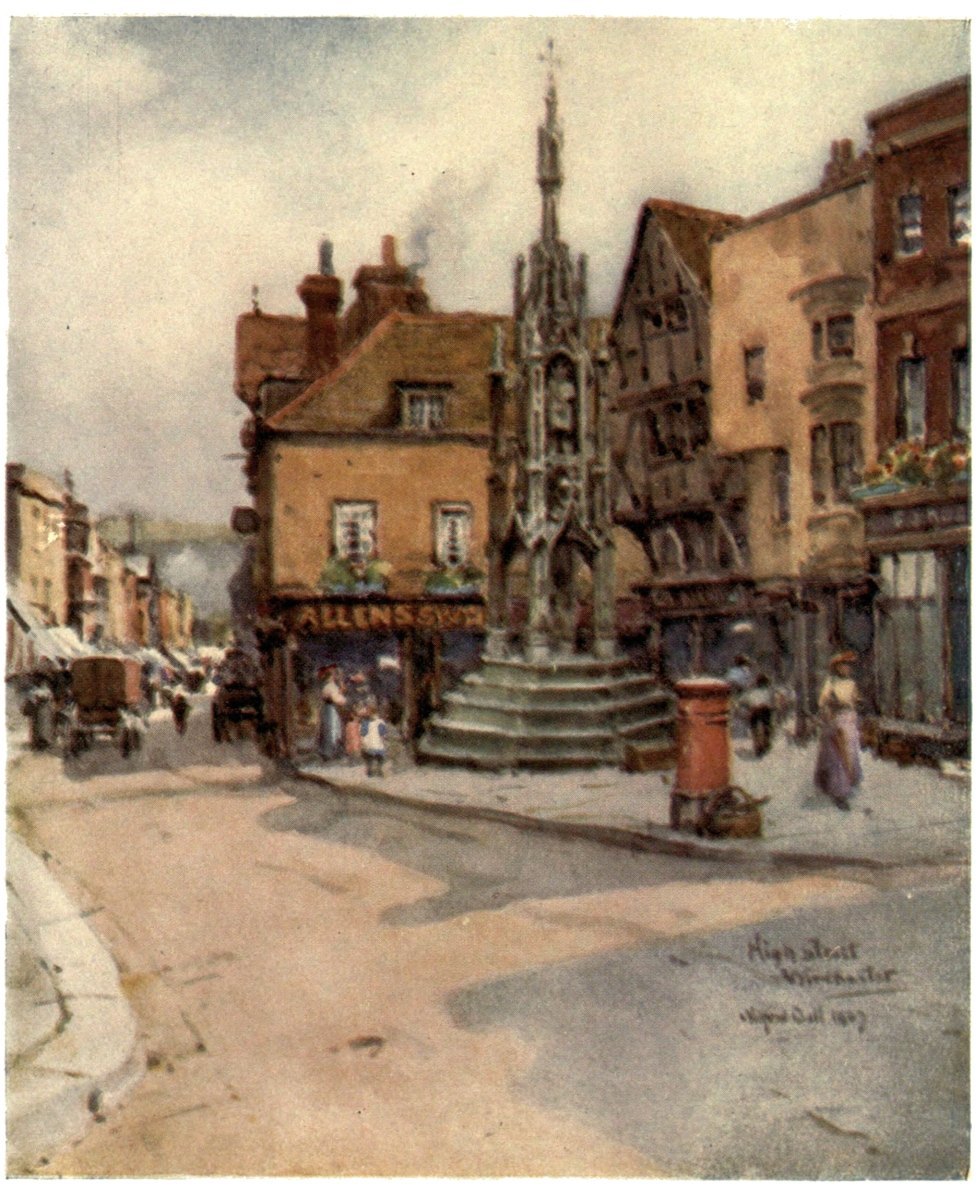

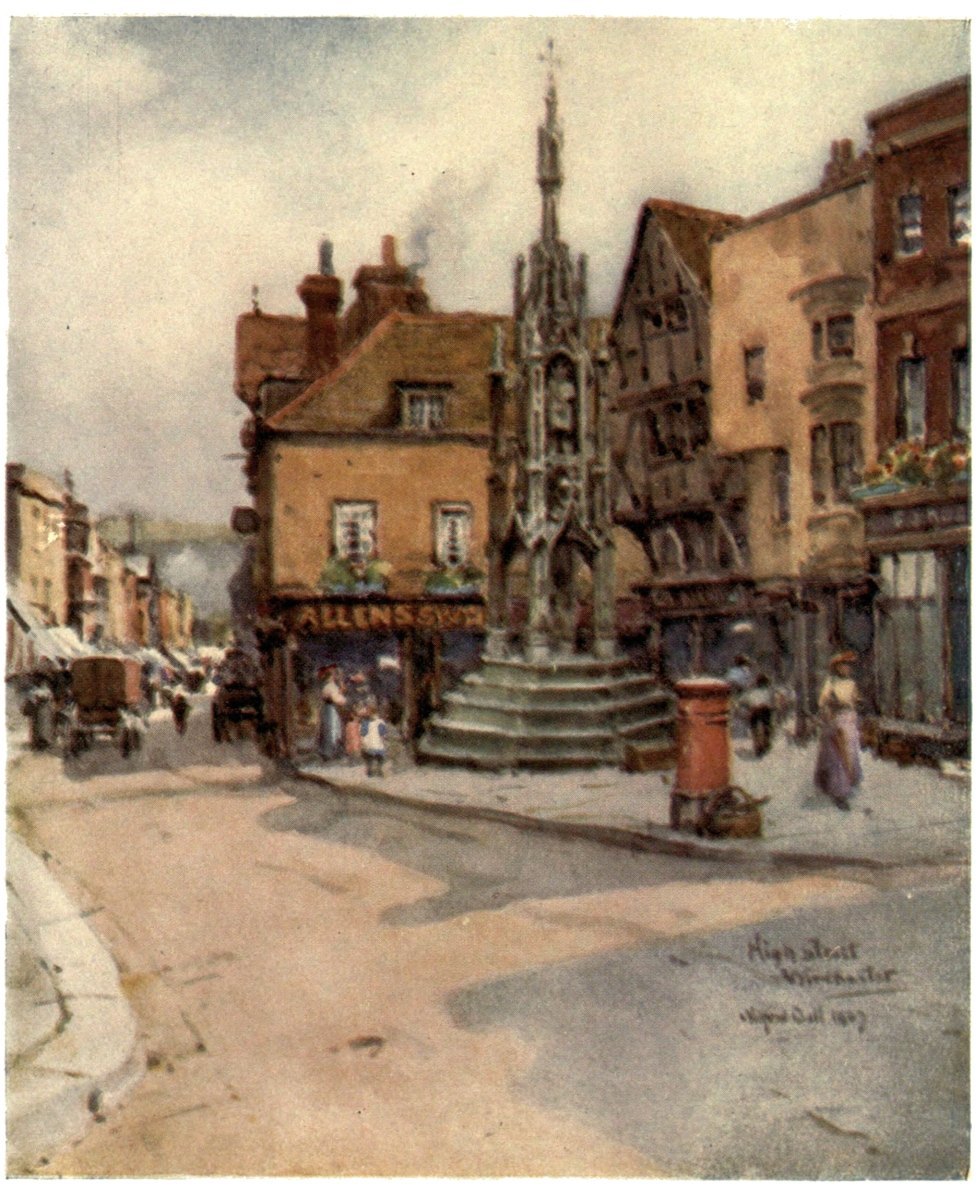

HIGH STREET, WINCHESTER

The ‘Butter Cross,’ as the City Cross is invariably denominated, forms the most characteristic feature of the delightful old-world High Street. Close by are the ‘Piazza,’ and a charming old timber-fronted Tudor house, now a well-known picture shop. Behind the Cross is the opening of ‘Little Minster Passage’ leading to the Cathedral.

In 1770 it was decided to remove the Butter Cross, and it was actually sold to a purchaser for this purpose, but the inhabitants rose in indignation, forcibly removed the scaffolding erected round it, and so preserved it from destruction.