CHAPTER VIII

ÆTHELWOLD, SAINT AND BISHOP

O see ye not yon narrow road

So thick beset with thorns and briars?

That is the land of righteousness,

Tho’ after it but few enquires.

THOMAS THE RHYMER.

WITH the death of Edwy in 959 a new chapter of interest opens, a period of revival, of growth, of development, the golden age of Saxon Winchester, during which the Saxon city was at its zenith of importance, the reign of Edgar the Peaceable and Magnificent.

The monkish chroniclers have for the most part painted Edgar in glossy colours; they sang his virtues, his magnificence, his piety, his love for Holy Church. They spoke of him as a second Solomon, and the comparison was in its way not inapt, for, like Solomon, he enjoyed peace and loved display; like Solomon, he allowed his private life to drag him to a low level; and, like Solomon, he left a son behind him, who was to see his kingdom rent asunder and a better than he bearing sway in it. But it is neither Edgar, who, with all his faults, ruled wisely, nor his son, Æthelred, of Evil Counsel, who, with all his vices, did not, who are the leading figures of interest at this juncture; neither is it the great Dunstan, of whom we get fleeting glances, Dunstan, the great archbishop, the master-mind of his time, in whose hands the would-be masterful and imperious king was indeed but as clay unto the potter, little though he realized it. It is Æthelwold the bishop, Æthelwold the saint and revivalist, Æthelwold the builder and lover of learning, who is the dominating figure, and it is rather by the commencement and completion of his work than by the accessions or deaths of kings that the limits of the period are to be assigned.

For estimating the course of Winchester history at this important and interesting stage we have fortunately more than an abundance—a wealth of historical materials. Not only do the English Chronicle and all the leading monkish chroniclers contain full references, but numerous other local sources of history, e.g. Rudborne, the various Winchester annalists, and the Liber de Hyda, exist, which deal fully with it. Besides these we have a minutely circumstantial life of Æthelwold himself, and, perhaps most interesting of all, a remarkable account by the same author, Wulfstan, precentor of Winchester, describing, in curiously involved and almost interminable Latin elegiacs, the wonders of the new Winchester cathedral which Æthelwold built, and the splendour of various great and striking ceremonies which he saw performed within it.

Æthelwold did more than merely leave his mark on Winchester; he transformed it. He found its ecclesiastical life poor, self-centred, and stagnant; he left it active, influential, creative; he found the Old Minster, with its cathedral church, bare, distanced, and neglected, eclipsed and outshone by Alfred’s later foundation, the Newan Mynstre. He left it not merely with an acknowledged ascendancy, but a new fabric, the finest in the land, the pride of the city, and almost one of the wonders of the age, a centre of pilgrimage of great resort and renown, with a new shrine containing a new patron saint, the wonder-working shrine of St. Swithun. He found the domestic buildings small, damp, unhealthy; he rebuilt them and brought to them a supply of pure water, irrigating the city and its river valley by streams whose courses still remain, to all intents and purposes, unchanged. Nullum tetigit quod non ornavit might well have been the epitaph over his tomb.

Ecclesiastical life in England had, in fact, never really recovered from the Danish débâcle of the later ninth century: monasteries had been burnt, plundered, impoverished: recovery had been but slow and partial: slackness and sloth were almost universal. It is not known how far in the earlier English monasteries the Benedictine rule and the common cœnobitic life had ever been strictly followed, but when Dunstan rose to influence there were practically no religious houses where monks were to be found; in their place non-resident canons, or seculars, as they were called, had become the established order of things, and the various annalists have painted for us in vivid colours the laxity and debased standard of the ordinary church life of the day. The canons, or ‘seculars,’ released from the severe toil and discipline of the Benedictine rule, allowed themselves numerous indulgences, and were in many cases even married. Loving comfort and ease, they neglected the church, and the daily services were grudgingly carried out by deputy, by ‘vicars’ paid, and paid poorly at that, to conduct the services while the absentee canons expended the income of their ‘prebends’ elsewhere at their ease. Thus Wulfstan tells us—

There were then in the Old Minster, wherein is the bishop’s stool, canons of disreputable manners and morals, so swollen with pride and insolence that numbers of them would not condescend to celebrate the masses when their regular turn came, who turned adrift the wives they had unlawfully married, and took others in their stead, and who gave themselves up to gluttony and drunkenness.

It is always interesting to note the snowball principle of accretion in the various annalists’ accounts, and the fifteenth-century Winchester annalist improves upon this picture, depicting them as

... canons, canonical only in name, who neglected their duties in the church, and left the pious labours of vigils and the service of the altar to be performed vicariously, absenting themselves from the sight of the church, or even, so to speak, from the sight of God. Bare was the church within and without. The vicars, scarcely able to keep body and soul together, could not give: the prebendaries would not. Hardly could you find one who, except on compulsion, would offer a shabby altar cloth or present a chalice worth a few shillings.

Be this as it may—and the monkish chroniclers would not be likely to spare the seculars—the standard of life was terribly lax, and Dunstan, originally abbot of Glastonbury, then Bishop of Worcester, and finally archbishop, set out, with King Edgar’s sanction, on the path of reform, and Æthelwold assisted heart and soul in the movement.

In their respective abbeys, Glastonbury and Abingdon, and in these only, monks had been re-established. Now the movement for the replacing of seculars by monks became general, and when in 963 he was consecrated Bishop of Winchester by Dunstan, Æthelwold set himself to revive the monastic orders in the three Winchester houses and elsewhere in the land.

The canons of the Old Minster, however, flatly refused to adopt the monastic life and discipline, and finally Æthelwold brought monks from Abingdon to replace them. Wulfstan relates their coming thus:—

It happened on a Sabbath in the beginning of Lent, as the monks from Abingdon were standing at the entrance to the church, that the canons were finishing mass, chanting together, “Serve the Lord with fear and rejoice unto Him with reverence. Take up the discipline, lest ye perish from the right way,” as if they should say, “We will not serve the Lord, nor keep His discipline; do you do it in your turn, lest, like us, ye perish from the way which opens the heavenly realms to those who follow righteousness.” Accepting this as an omen, one of them exclaimed, “Why do we stand still outside the church? Let us do as these canons exhort us; let us enter and follow the paths of righteousness.”

The canons, however, struggled hard for reinstatement. They appealed to the king, who inclined to temporize with them, and a great meeting of the Witan was convened at Winchester, where Dunstan and Æthelwold urged strongly the monastic view. The king, however, was still undecided when a voice was heard from the crucifix built against the walls bidding him not to waver longer. Thus, so the Liber de Hyda informs us, the monks were confirmed in occupation.

Next year it was the turn of the canons of the New Minster to follow suit, for, in the words of Wulfstan, “thereupon the eagle of Christ, Bishop Æthelwold, spread out his golden wings, and, with King Edgar’s approval, drove out the canons from the New Minster, and introduced therein monks who followed the cœnobitic rules of life.” The Nunnery, St. Mary’s Abbey, was at the same time placed under the strict Benedictine rule.

And now events moved fast, and with monks established in the monastery strange rumours and portents began to prevail. It was noised abroad that the saintly Swithun, buried humbly in the common graveyard on the north side of the church, had begun to manifest his virtues by acts of healing at his tomb. The churchyard became the resort of crowds of pilgrims, until

... the holy father, Æthelwold, warned by a divine revelation, translated the holy Swythun, the special saint of this church at Wynchester, from his unworthy sepulchre, and piously placed his holy relics with due honour in a shrine of gold and silver given by the king, and worked with the utmost richness and craftsman’s skill.

The same account tells us that the bones of St. Birinus were similarly deposited in another shrine, but St. Swithun was the popular saint, and the miracles wrought at his shrine soon made the Old Minster renowned throughout the whole land.

Indeed, as Rudborne, the monk, quaintly and naïvely tells us, “as long as canons held the Church at Winchester there were no miracles performed, but no sooner were they ejected and replaced by monks than miracles were wrought abundantly.” Doubtless Rudborne was right. At all events crowds of pilgrims thronged to Winchester, and the name of Swithun, the Saxon saint, became a power in the land.

But all this time Æthelwold was at work rebuilding the Cathedral, and the church he reared was the finest in the land—one of the wonders of the age.

Wulfstan in his long-winded way describes the building, its aisles, its towers, its crypt, both mystifying the reader and losing himself over and over again in the description, as he relates how the newcomer passes bewildered from one wonder to another, till he knows neither how to advance nor to get back again.

Nesciat unde meat, quove pedem referat.

The gilded weather-cock on the top of one of the towers in particular fired his imagination. Glorious and superb, it grasped the ball of empire with its splendid talons, and from its lofty standard dominated the whole populace of the city:—

Imperii sceptrum pedibus tenet ille superbis,

Stat super et cunctum Wintoniae populum.

The mighty organ placed in the church by Æthelwold’s successor he also enlarges upon. This mighty instrument had twenty-six bellows—twelve above, fourteen below—worked laboriously by seventy full-grown men, who sweated at their task, while two organists hammered vigorously upon the manuals, flooding the whole city with the volume of the sound.

Wulfstan not only gives us these details of the building, but he describes the various splendid ceremonies which he himself witnessed within it—the translation of St. Swithun’s bones in the presence of King Edgar; the dedication in 980, when King Æthelred and nine bishops were present, including the “white-haired and angelic Dunstan”:—

Canitie nivens Dunstan et angelicus.

Then of the feast which followed, telling us how a tenth bishop—one Poca—who arrived too late for the labours of the ceremony, atoned for it amply by the depth of his potations.

Nulla laboris agens, pocula multa bibens.

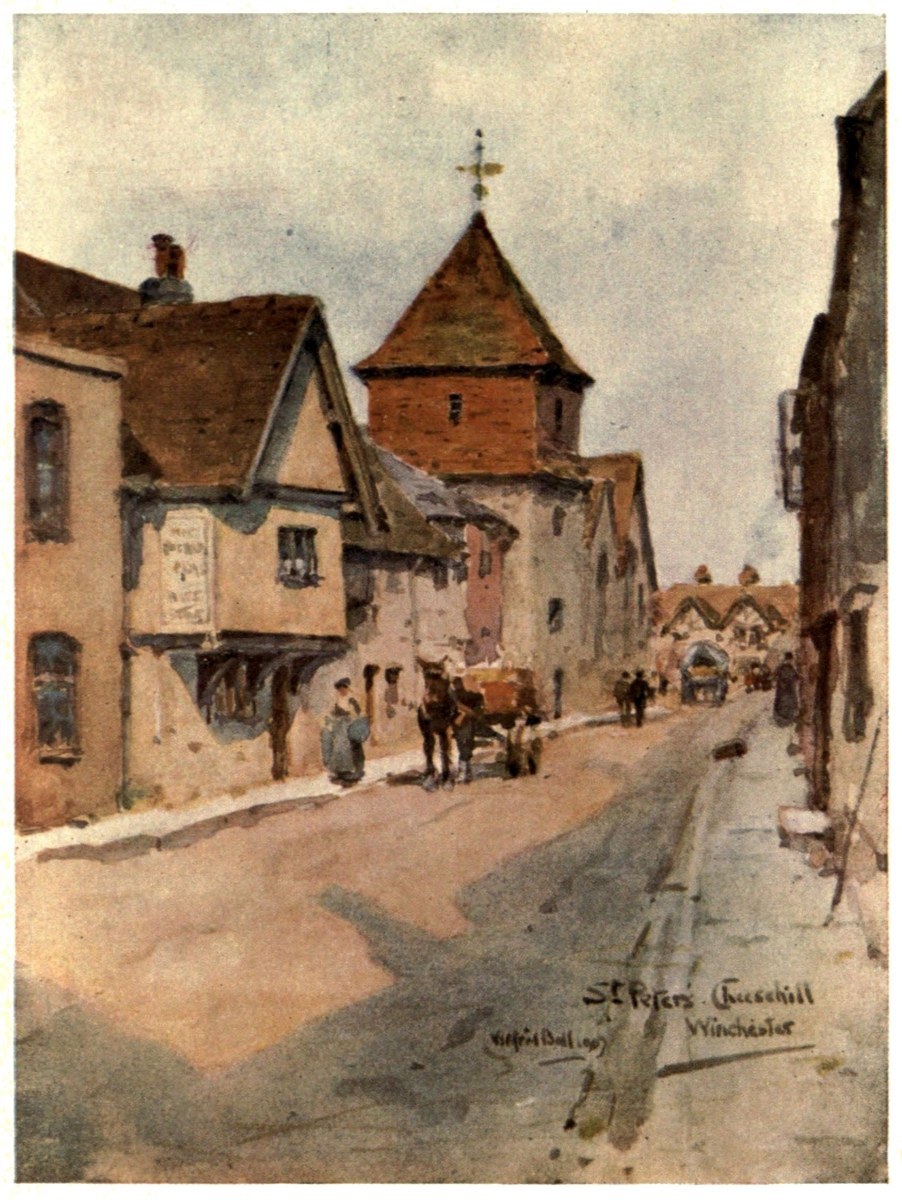

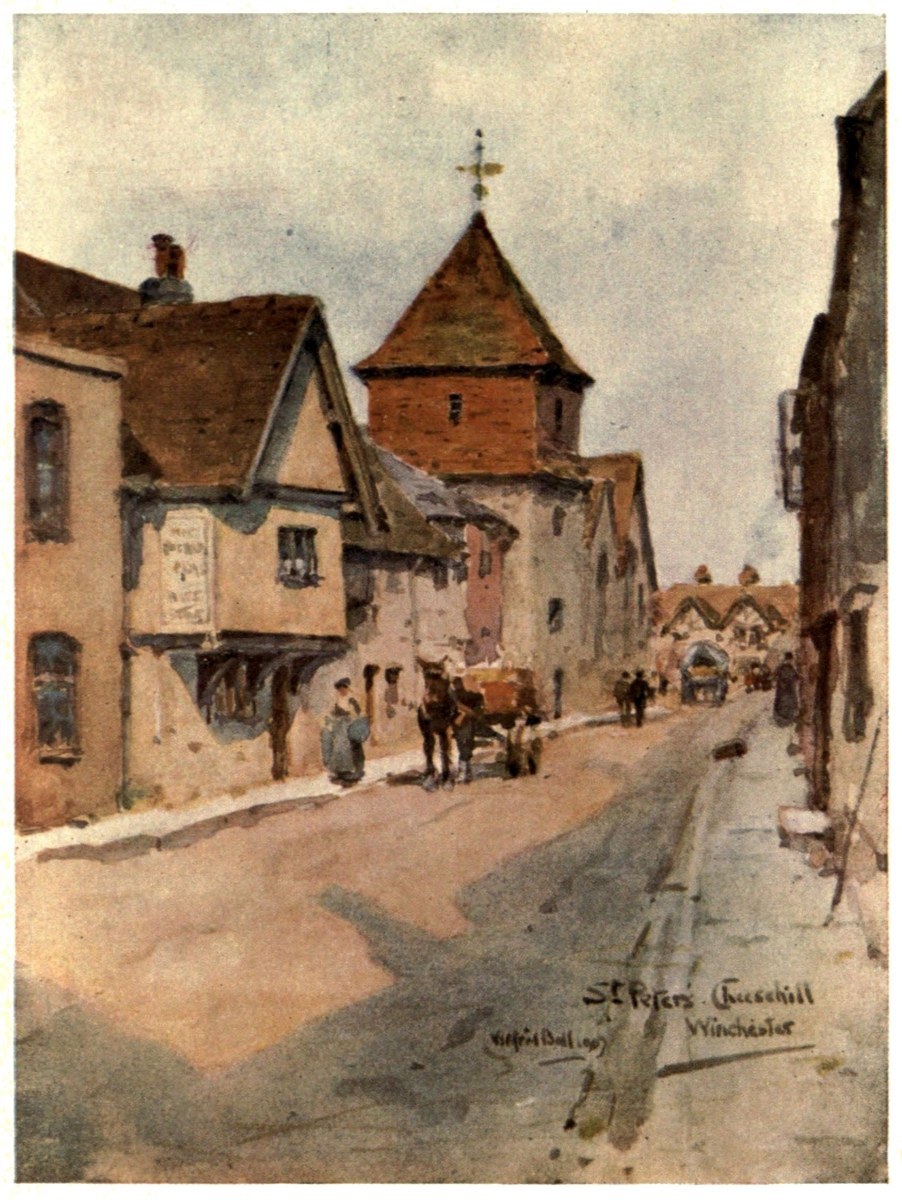

ST. PETER’S, CHEESEHILL, WINCHESTER

One of the oldest of Winchester Parish Churches, of Norman date. Cheesehill—a corruption of Chesil—a word still surviving in Chesil Beach, near Portland—denotes the dry or gravelly strand along the bank of the Itchen, and has no connection with cheese. Cheesehill Street, though somewhat ‘slummy,’ is very picturesque and contains many interesting old houses.

Later on there was a second dedication. Altogether it was a period of splendid and impressive ceremonial.

Æthelwold’s monks displayed their zeal in another channel. In both monasteries scriptoria were established, and Winchester became the centre of an unrivalled school of MS. illumination. The MS. treasures of Æthelwold’s monks may still be seen in the British Museum, in Winchester Cathedral Library, at the Bodleian, and at Rouen. Loveliest of all is the priceless ‘Benedictional of St. Æthelwold,’ the glory of the Chatsworth collection, a MS. of rare beauty and interest, for it preserves for us the figure and features of St. Æthelwold himself as well as some of the architectural details of the new cathedral he had erected. How the ‘Benedictional’ came into the possession of the Cavendish family is unknown. Is it too much to hope that later on the day may come when such a treasure may be restored to its natural home—the Cathedral Library at Winchester?

Æthelwold’s last work for Winchester we have already mentioned—the rebuilding of the monastery. He transformed the channels of Itchen, and brought its purifying waters through the city and the monastery by fresh courses.

Quoting again from Wulfstan:—

Hucque

Dulcia piscosae flumina traxit aquae

Successusque laci penetrant secreta domorum

Mundantes locum murmure coenobium,

Here great Æthelwold led sweet fishful courses of water.

And murmurs of mingling streams pervade the recesses monastic.

Such, then, was Æthelwold. In 984 he died, and was buried in the crypt of the cathedral he had erected. The place of his sepulture is now unknown. There are few among the makers of Winchester greater than he.

We have dealt with this era of constructive effort as if the full design was brought to completion in Æthelwold’s lifetime. Such was not indeed the case, and it was left to Ælfeah, his successor in the episcopate, to actually finish the building schemes inaugurated by his predecessor. But it was Æthelwold, not Ælfeah, whose creation it really was, and Ælfeah (St. Alphege) will always be remembered more feelingly as the Archbishop of Canterbury, martyred by the Danes, rather than as the completer of Æthelwold’s great master-work in Winchester.