CHAPTER IX

THE CAPITAL OF THE DANISH EMPIRE

Saxon and Norman and Dane are we.

ÆTHELWOLD’S work was still in full progress when King Edgar died in 975. Young as he was—he was only some thirty-two years old when he died—he had reigned for some sixteen years, and his reign had had notable results. It had been a reign of uninterrupted peace; indeed it was the only peaceful reign, save Edward the Confessor’s, of any Saxon king in England, and a reign, moreover, of good government and wise laws. And though the memories of Edgar’s domestic life, his intrigues, and his tragic murder of his false friend, Earl Æthelwold, belong rather to Wherwell and Andover than to Winchester, we have many personal touches reminding us of his close connection with Winchester history. We see him holding his court continually at Wolvesey. Tradition even derives the name of Wolvesey from the wolf’s head tribute which he caused to be paid to him there, and which brought about the practical extermination of wolves in the land; but be that as it may, at Wolvesey Edgar royally kept his state, presiding over many a great meeting of the Witan, and promulgating his laws with the imperious formula, “I and the Archbishop”—an involuntary acknowledgment of what was, after all, the great power behind the throne, the influence of Dunstan. We see him attending the imposing ecclesiastic ceremonies of his reign, such as the enshrinement of the bones of Swithun, and we read of the wise laws and reforms he inaugurated. He standardized the coinage and the weights and measures of the realm. “Let one weight and one measure be used in all England, after the standard of London and of Winchester.” “Let there be one standard of coinage throughout the king’s realm”—regulations which serve to show the development of commerce and prosperity in the kingdom. Another was a curious law passed to check the excessive drinking habits to which in particular his Danish subjects were addicted. Pegs were placed at certain intervals in the drinking cups, and no one was suffered to “drink below his peg.” Yet notable as King Edgar was as a king, his personal claim entitles him to little respect. Allowing fully for the lowly standard of his age, his life was sensual, loose, and so smirched with squalid self-indulgence that even his monkish admirers, who had every reason to laud him highly, were forced to mingle censure with the lavish encomiums they heaped upon him, and it was a bitter legacy which his loose domestic life left behind him for the nation to inherit. The national record, the English Chronicle, accords him an appreciative but discriminating epitaph, praising his good rule and reciting his virtues indeed, but concluding in words which we can all at least re-echo:—

May God grant him

that his good deeds

be more prevailing

than his misdeeds

for his soul’s protection

on the longsome journey.

And now followed years of tragedy and strife. Edgar’s elder son, Edward, was very soon murdered by his stepmother, Ælfrida, and the throne passed into the hands of Edgar’s second son, Æthelred the Redeless, or Æthelred of Evil Counsel, the feeblest, most inept, most hopeless of all our monarchs, whether Saxon or English. His reign was to witness the recrudescence of Viking inroad and savage assault, and when, after bleeding the resources of the realm to death in a vain and hopeless effort to buy off the invaders, his foolish brain conceived the wickedness of murdering all the Danes in England—a fatuous and desperate act of villainy, hatched at Winchester and consummated on St. Brice’s Day 1002—the tragedy of misery was exchanged for the ruin of despair, and the terrible vengeance the Danes exacted was only ended by the conquest of the realm and the passing of it into Danish hands, and so Winchester became the capital of a greater empire than ever before or since—the capital of the great Scandinavian empire of Cnut.

Most striking of all the figures of this period, more interesting far than the ignoble king, was Æthelred’s queen, Emma, daughter of Richard, Duke of Normandy, the beautiful, fascinating, and designing woman whom for her beauty the Saxons called Ælfgyfu Emma—Emma, the gift of the elves—whom Æthelred married at Winchester in 1002. A rare personality this Ælfgyfu Emma, but not a pleasing one. “I governed men by change, and so I swayed all moods,” she might have said of herself. The wife of two successive kings, and the mother of two more, she was to be for fifty years, and during five successive reigns, the central influence in Winchester history; for Æthelred on the day he married her presented Winchester and Exeter to her as her ‘morning gift,’ or wedding present, and when he died, Cnut the Dane, Æthelred’s successor, wedded her in turn. Of the details of her career we have yet to speak more fully, and after Cnut’s death she ‘sat’ or kept her court at Winchester for many years as the ‘Old Lady,’ the beautiful Saxon phrase for Queen Dowager. Her memory lingers now most closely around the charming old Tudor building, Godbegot House, fronting Winchester High Street, which occupies the site and still re-echoes the name of a little manor which once belonged to her—the little manor of Godbiete. Queen Emma granted it to the prior and convent of St. Swithun, “Toll free and Tax free for ever,” and toll free and tax free it remained for years and years, wherein none had right of access, and even the king’s warrant lost its authority. And so for some hundreds of years the liberty of Godbiete remained a source of division and evil influence, a sanctuary or ‘Alsatia’ right in the heart of the city, where those obnoxious to the law might shelter and defy its terrors. For “no mynyster of ye Kinge nether of none other lords of franchese shall do any execucon wythyn the bounds of ye seid maner, but all only of ye mynystoris of ye seid Prior and convent”—a rarely suggestive illustration of mediaeval life and method. Destined ever to bring trouble with her in her lifetime, her very legacy seemed to bear with it the same evil fruit of civil disturbance to the city and much bickering of rival authorities for centuries after her death.

Of Winchester in Cnut’s reign we have frequent mention in the chronicles of the time. The story of Cnut rebuking his courtiers on the seashore at Southampton we need not repeat, except as regards its sequel. “After which,” to quote Rudborne’s account, “Cnut never wore his crown, but placing it on the head of the image above the high altar of the cathedral (at Winchester), afforded a striking example of humility to the kings who should come after him.”

Nor was humility the only virtue Cnut displayed. His munificence to the Church was striking and ample, and one chronicler after another the gifts made by Cnut and Emma jointly to the religious houses both at Winchester and in the district round. “This same Cnut,” we read, “embellished the Old Minster with such magnificence that the gold and silver and the splendour of the precious stones dazzled the eyes of the beholders.” Two of Cnut’s gifts were indeed to become memorable in after years. One was the great altar cross of solid gold which he and Queen Emma presented jointly to the New Minster, a presentation quaintly portrayed in the Liber Vitae of Hyde, a register and martyrology illuminated at Winchester during this reign. For years it remained the glory of the houses till it was destroyed at the burning of Hyde Abbey, and even then its history was not ended, for Bishop Henry of Blois, having stolen the precious metal mingled with the ashes from the conflagration, was forced by the monks of Hyde to make restitution. The other historic gift was that made to the Old Minster, of “three hides of land called Hille,” usually identified as St. Catherine’s Hill, whereon, in centuries to come, generation after generation of Wykeham’s scholars were to make regular pilgrimage for purposes of play on ‘remedies’ or days of relaxation. The land is still Church property, and is held now by the ecclesiastical commissioners.

Cnut is a great figure both in Winchester and in English history. Foreigner though he was, he ruled not as an alien conqueror, but as an English monarch, and Englishmen are proud to claim him as one of the greatest among our national rulers. He died in 1035, and his body was brought to Winchester for interment in the Old Minster, and in the Cathedral his bones are still preserved in one of the mortuary chests already referred to, along with those of Emma his queen, and—strange companionship—William Rufus also.

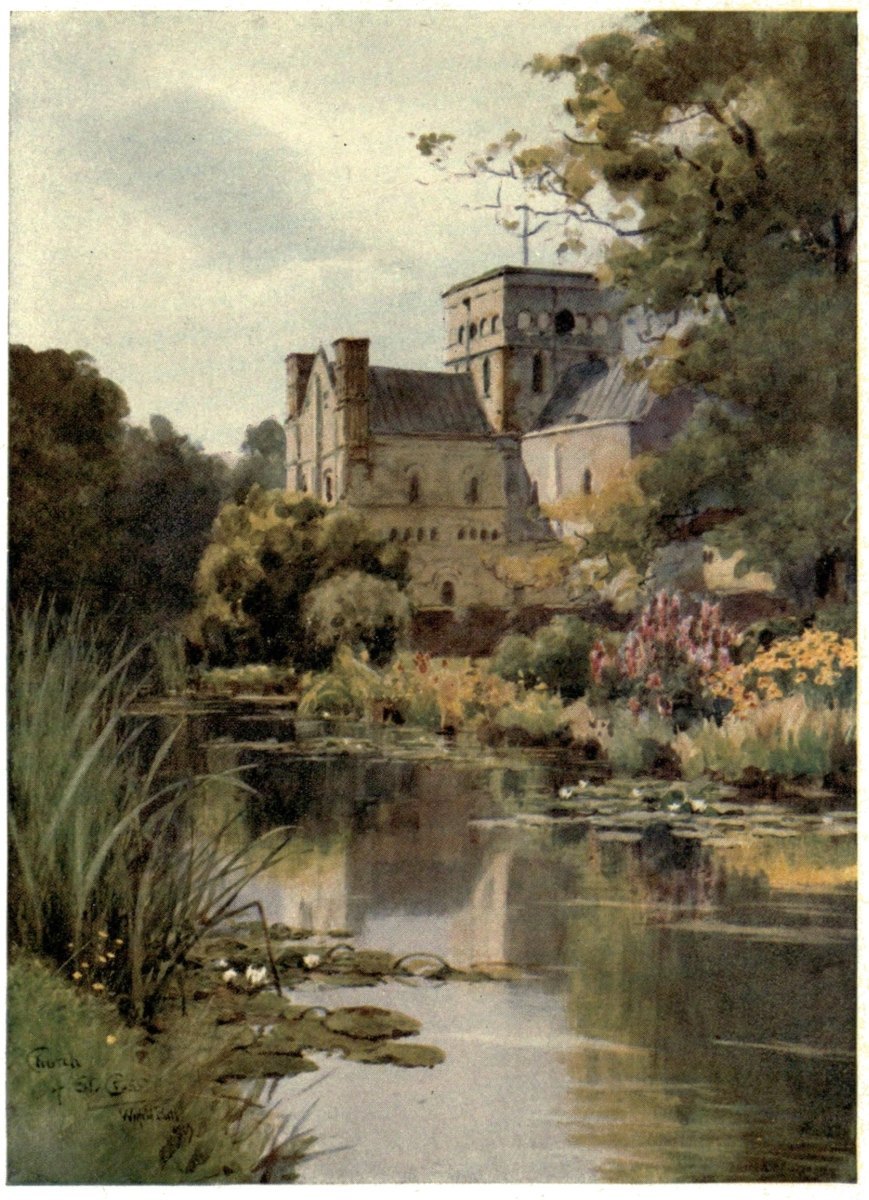

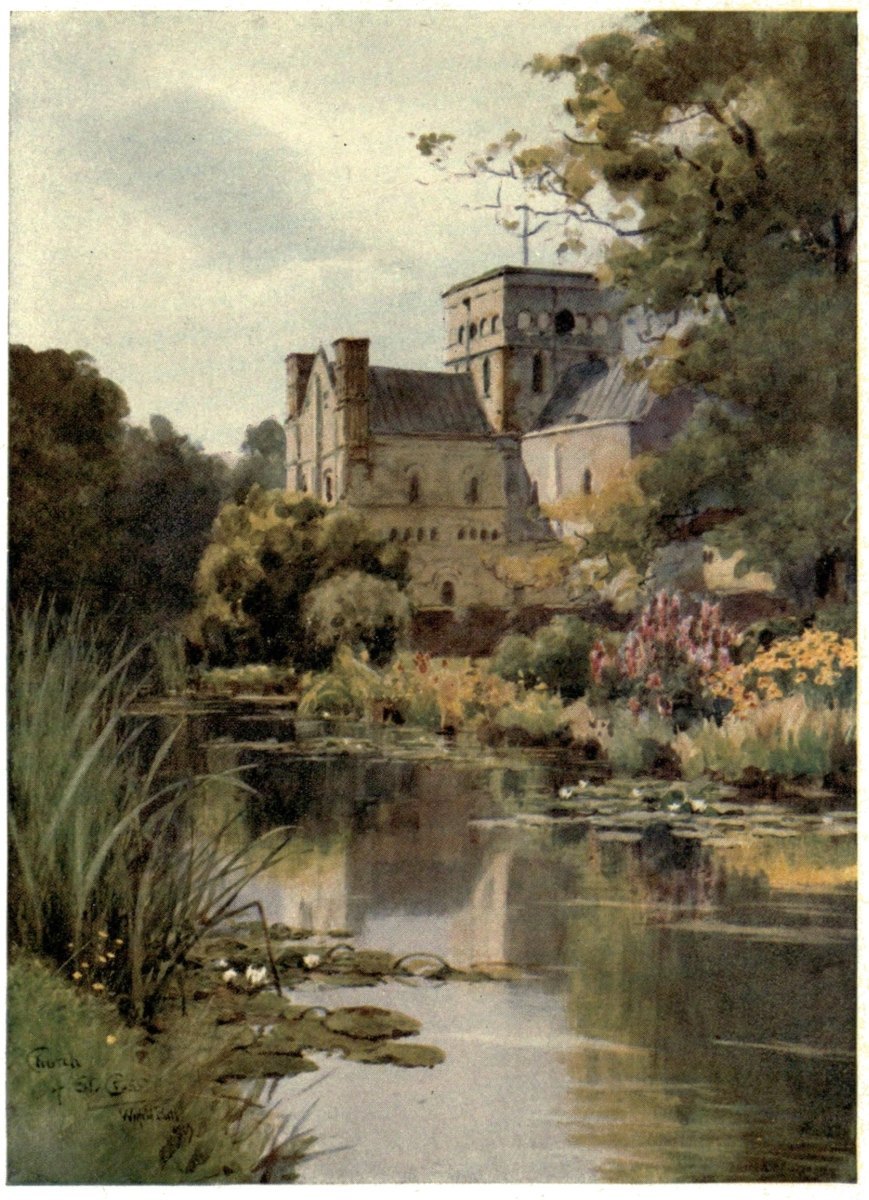

CHURCH OF ST. CROSS

St. Cross Hospital founded by Bishop Henry of Blois in 1136, and placed by him subsequently under the protection of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, from which circumstance the Brethren wear the characteristic croix pattée or eight-pointed cross of the Order.

Cardinal Beaufort built ‘Beaufort’s Tower’ and most of the present domestic buildings, and founded the Order of Noble Poverty.

The hospitality to travellers for which the Knights Hospitallers were noted is still practised in the form of the ‘Wayfarer’s Dole’ of bread and ale, dispensed at the hospital gates to those applying for it, very much as in mediaeval days.

With Cnut’s death came faction and strife. Cnut’s two sons, Harold and his half-brother Harthacnut, Æfgyfu Emma and Earl Godwine, had all intrigued desperately for power. The various accounts differ, but Harthacnut, who, as son of Emma and Cnut, had a strong following in the country, was abroad at the time, and in his absence Harold secured the throne. Emma had played her cards well, perhaps too well, for she had managed to secure possession of Cnut’s treasure and to assert her influence as ‘lady paramount’ over Wessex, for we read

... it was resolved that Æfgyfu, Harthacnut’s mother, should dwell at Winchester with the king, her son’s hûscarls, and hold all Wessex under his authority.

But this was not to last. Harold asserted himself and raided his ‘mother,’—she was his stepmother, of course,—while

... Ælfgyfu Emma, the lady, sat then there within, and Harold ... sent thither, and caused to be taken from her all the best treasures which she could not hold which King Cnut had possessed; and yet she sat there therein the while she might.

Nor was this all. Harold’s violence became impossible to make head against, and the poor queen was driven into exile

... without any mercy against the stormy winter, and she came to Bruges beyond sea, and Count Baldwine there well received her ... the while she had need.

And so, for some three years, both Emma and Harthacnut were fugitives at Baldwin’s court, till on the death of the violent and worthless Harold, some three years after, they returned. Harthacnut, equally inglorious, reigned some two years only, and actually died during his own marriage feast as he stood up to wassail his bride. His body was brought to Winchester for interment in the Old Minster, as a modern inscription in the Cathedral serves to remind us; while his mother enriched the New Minster with a gruesome relic—the head of the blessed Saint Valentine the Martyr—to pay for masses for his soul. Then in 1043 came Edward the Confessor, son of Emma and Æthelred the Redeless, who was “hallowed king at Winchester on the first Easter day”; and the realm had peace at least, if not rest, for over twenty years.

Since her return to England, Emma, ‘the lady,’ had not been idle, for at the accession of the new king she was not only re-established in all her old supremacy, but had recovered much of the wealth which Harold had wrested from her, and the remaining seven years of her life witnessed a continual struggle for ascendancy between her and Edward her son. Edward had no sooner been crowned than he set himself to seize her treasure—doubtless it was national rather than personal property—but Emma, skilled to fish in troubled water, had landed both loaves as well as fishes in her net, and this time Godwine the earl, unfortunately for her, cast his weight into the opposing scale; accordingly, six months after Edward’s coronation, we read—

The King was so advised that he and Earl Leofric, and Earl Godwine, and Earl Siward, with their attendants, rode from Gloucester to Winchester unawares upon the Lady (Emma), and they bereaved her of all the treasures which she owned, which were not to be told ... and after that they let her reside therein—

a passage notable in its way, for it brings before us, in close juxtaposition, practically all the great characters of the Confessor’s reign—Ælfgyfu Emma, and the king her son, and the three great earls, with their attendants—Godwine, the great Earl of Wessex, accompanied possibly by his sons Harold and Tostig: Leofric, Earl of Mercia, the ‘grim earl’ of Tennyson’s poem, husband of the famous Godiva: and Siward, Earl of Northumbria, the old Siward of Shakespeare’s Macbeth—and suggests a striking subject for pictorial representation, which as yet, unfortunately, no artist’s brush has attempted. It was doubtless in the national interest that the three rival earls were led to combine to support the king against his mother, but we cannot but regret that the circumstance which united this notable and noble trio together in the support of the king—probably the only occasion in his reign when the king ever commanded their united support—should not have been one more heroic than that of forcing a defenceless if grasping old woman to render up the keys of her treasure-chest.

We have one more picture of the ‘Old Lady’—the legend of Queen Emma and the ploughshares, a legend peculiarly characteristic of mediaeval sentiment, which is quaintly narrated in full and charming detail by more than one chronicler. Her enemies had slanderously connected her name with that of Alwine, Bishop of Winchester, and she had appealed to the ordeal by fire to clear her reputation.

Coming from Wherwell Abbey, where she had been forced to retire for refuge, she had passed the night in prayer and fasting, and in the morning, in the presence of the king and a great concourse of people, she had been led forward by two bishops, to pass barefooted over nine red-hot ploughshares laid in order in the nave of the Old Minster church. Yet such was the potency of the protection she derived from her blameless conduct and unsullied conscience, that she was not only unharmed but had actually passed over the ploughshares before she became conscious that she had even reached them, whereupon the king, overwhelmed with contrition and remorse, implored her forgiveness, in the words of the repentant prodigal: “Mother, I have sinned against Heaven and before thee and am no more worthy to be called thy son”; while in token of his sincerity he presented his own body before the queen and the bishops for punishment. The bishops touched him each with a rod, after which the pious king received three strokes from the hand of his weeping mother.

The Winchester chronicler, conscious of a ‘divided duty,’ has managed very dexterously to extricate the king from severe censure, while honourably loyal to the lady paramount of his city. In 1052 Emma died, and was buried by her second husband’s side in the Old Minster. Her bones still rest, as already mentioned, mingled with his, in one of the Cathedral mortuary chests.

After Emma’s death Edward the Confessor was frequently at Winchester; he revived the practice of the earlier Saxon kings, and “wore his crown at Winchester at Easter time”—in other words, held his Easter Court there. Into the details of his reign we need not enter. Most striking, perhaps, from the point of view of our Winchester annals, is the amazing accumulation of extravagant legend, beneath which the history of this reign is buried and obscured. One such legend we have just related; another one is that of the mysterious death of Earl Godwine. The Chronicle records the circumstance briefly and naturally. “On the second Easter day he was sitting with the king at refection (doubtless at Wolvesey) when he suddenly sank down by the footstool, deprived of speech and of all power.... He continued so, speechless and powerless, until the Thursday, and then resigned his life, and he lies within the Old Minster.” A plain story, plainly told—an old man, a sudden stroke of paralysis, and death in its natural course. But not so in the hands of the fifteenth-century annalist; the story had grown, by the snowball principle, by then: Godwine was no friend of the monks, and Edward was a Saint—the Confessor. Godwine in this account, while feasting at the royal table, is under grievous suspicion of compassing the death of the king’s brother, Alfred the

Ætheling. A cupbearer, in handing the cup to the king, slips with one foot on the floor, but dexterously recovers his balance with the other foot. “Thus,” remarked Godwine, “brother brings aid to brother.” The king retorts fiercely, “But for the wiles of Earl Godwine, my brother would have been able to bear aid to me.” The earl earnestly protesting, and in token of his innocence, lifts a piece of bread, praying that it may choke him if he is in any way complicated in the crime of murder. The pious king solemnly blesses the bread, which proves a fatal mouthful, for “Satan entered into him when he had received the sop,” and the earl falls speechless before the incensed king, who spurns the body with his foot, while his sons Harold and Tostig remove it, and later on bury it surreptitiously in the Cathedral. So was history written ‘once upon a time.’ Whereabouts in the Cathedral the great earl was buried is unknown.

One more legend—for legend, unfortunately, we must so deem it—the legend of Abbot Alwyn and the monks of Newan Mynstre, and we must conclude. Edward’s reign is marked by the struggle between Saxon and Norman interest for supremacy in England, and to the Confessor Norman art, Norman culture, Norman thought were dear. Doubtless his instinct was so far right, but, unaccompanied as it was by any national sentiment or attachment, this predilection must be accounted in him a weakness, and not a virtue, and opposition to the king’s policy took on a national and therefore patriotic colour. This was reflected in the

Winchester religious houses, and the Newan Mynstre, staunch in its attachment to the Saxon cause, became the rallying point for Saxon patriotism, while the Old Minster had leanings towards the Norman cause. Thus it came about that when, on the Confessor’s death, Harold marched to Senlac to repel the Norman invader, Abbot Alwyn and twelve monks of Newan Mynstre donned coats of mail, shouldered each a battleaxe, and fought sternly and heroically in defence of the cause.

There, in the thickest of the fight, they plied their axes bravely, and when all was over their bodies were found, lying dead round the dead king’s banner, and it was seen from their habit that they were monks of the New Minster at Winchester. The Norman Conqueror, on being informed of the discovery, remarked with grim irony that “the Abbot was worth a barony, and each of the monks a manor,” and mulcted the New Minster accordingly. The story, which is to be found in Dugdale’s Monasticon, is picturesque and appealing—unfortunately there is no confirmation of it. It is not given in the Chronicle, nor in any local sources such as the Hyde Abbey records (where assuredly it would have been preserved), in Rudborne, or the Annales de Wintonia. Rudborne gives, indeed, a long list of lands which the Conqueror deprived the New Minster of, but that in itself would be no confirmation of the story, for in the same passage he states that William also seized lands belonging to the Old Minster. William, it is true, kept the Abbacy of the New Minster vacant for some two years, but that again was but an act of minor tyranny, too familiar to call for much remark. The story, indeed, appears to be quite discredited by the entries in Domesday Book, which seem to afford no evidence of spoliation, but rather to prove that the New Minster lands were added to by William, while the Old Minster certainly suffered at his hands; and we fear that the story of the abbot and the twelve monks of New Minster must, like so many others, be offered up reluctantly as one more sacrifice on the altar of historical accuracy. The subject may be pursued in the Victoria History of Hampshire, where it is fully discussed.

With Harold’s death on Senlac field Winchester opens on a new phase. Saxon history in Winchester is glorious and fascinating, but of Saxon buildings in Winchester few visible traces remain. Norman Winchester is with us still, and under the Normans Winchester was to expand and attain greater outward beauty and glory than perhaps a thousand years of undiluted Saxon rule would ever have conferred upon her.

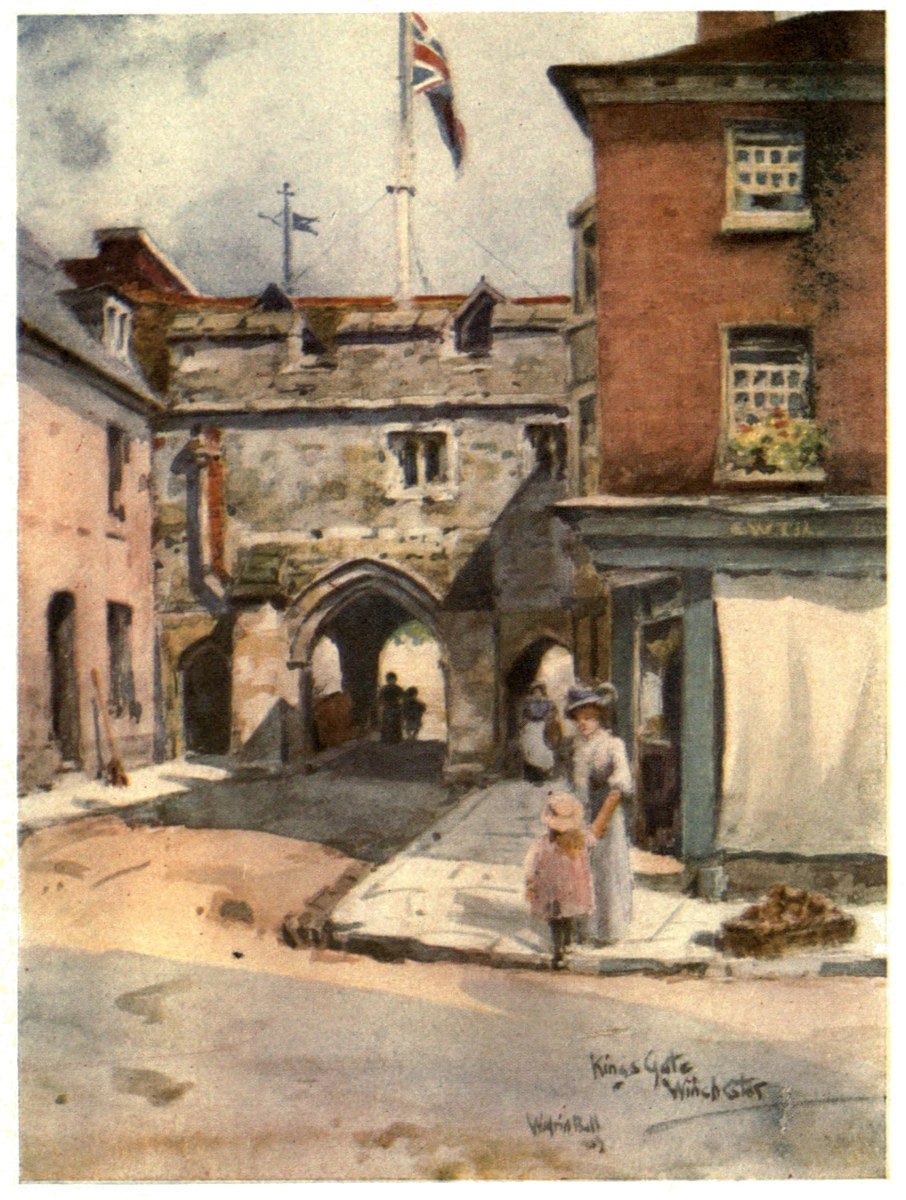

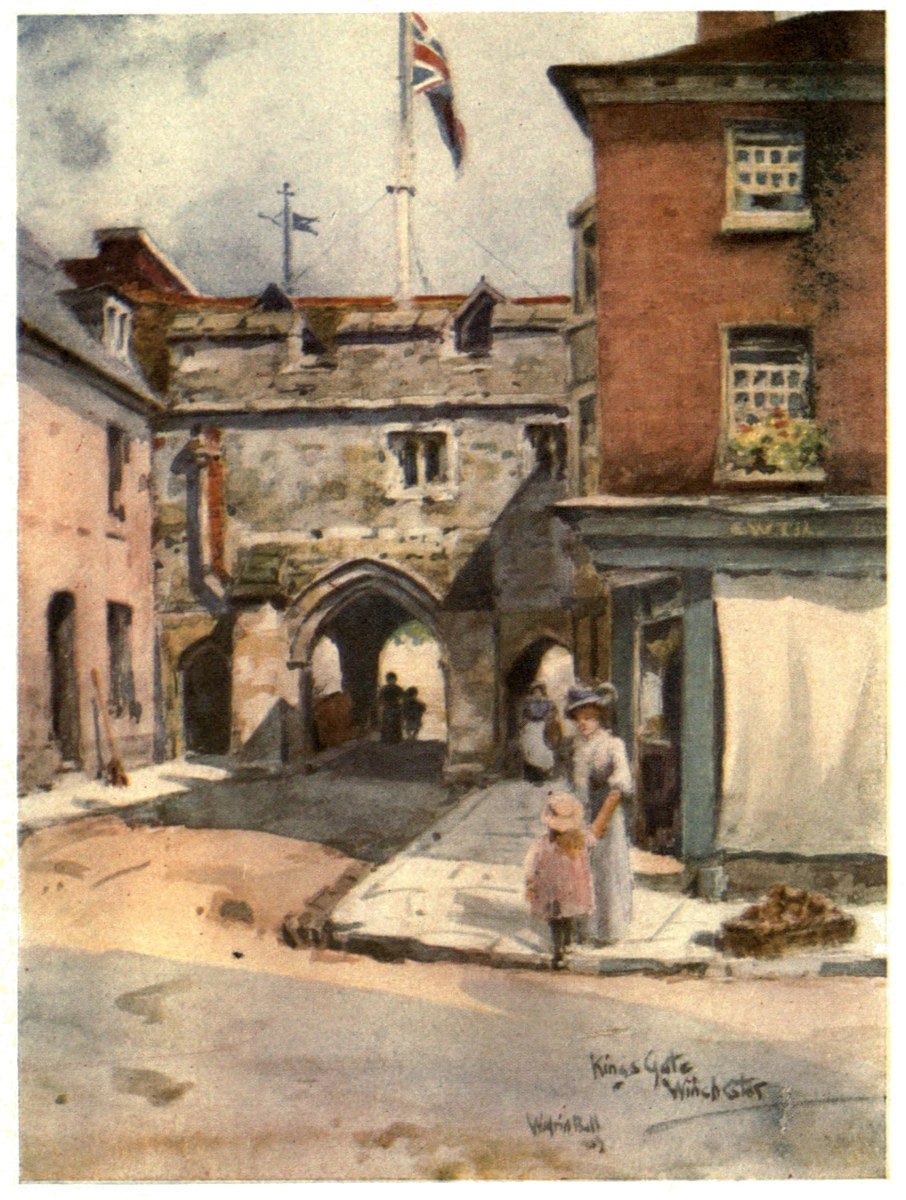

KING’S GATE, WINCHESTER

The smallest of the five original gates of Winchester, of which it and Westgate alone are standing now. Abutting on the great gate of St. Swithun’s Priory—now the Close Gate—it was burnt down during the Barons’ War, and when rebuilt a small church was built above it for the use of the lay servitors of the Priory. This church is now the Parish Church of St. Swithun’s, Winchester. An absurd local tradition connects the name with the number of sovereigns of the realm who have passed beneath it.