CHAPTER XV

THE MONASTIC LIFE

Grosse Städte, reiche Klöster

Schaffen, dass mein Land den euren

Wohl nicht steht an Schätzen nach.

KERNER, Der reichste Fürst.

BUT active as were the currents that circulated in and round the gilds, the wool markets, the annual fair, and the pilgrimage resorts, the dominating stream was that which flowed through the monastic channel, and over mediaeval Winchester the influence of the monastery in one form or other, whether of priory, abbey, or nunnery, or whether of the mendicant orders, or nursing sisterhoods, now for a considerable time firmly established in the city, was supreme.

The Priory was a secluded area, the privacy of which was jealously guarded. The Cathedral itself, from the eastern angle of the north transept to the southern corner of the west front, formed the effective boundary on the city side, with the great churchyard lying between it and the city proper. The remainder was supplied by the high close-wall running all round it, much as the greater part of it does now, flanked to the east by the boundary of the Bishop’s residence at Wolvesey, and forming, with the latter, part of the external defences of the city, so that between them the monks and the Bishop relieved the citizens of something like a quarter of the burden—a heavy one at that time—of keeping the walls in repair and defending them if attacked.

The main entrance was then, as now, the great close-gate, opening into Swithun’s Street near Kingsgate,—the point of attack in the troubles of 1264—and besides this a small postern or opening gave access from ‘Paradise’—as the area east of the northern transept was and still is called—to Colebrook Street and Paternoster Row. From the churchyard to the domestic quarter no direct means of access existed; the ‘Slype’ or passage through the great south-western buttress was not yet made, and to pass from the west part into the cloister it was necessary to pass through the Cathedral itself.

The domestic buildings—as was always the case with the Benedictines, and St. Swithun’s was a Benedictine house—were grouped on the south. The cloister garth was a square enclosure, south of the nave, roofed overhead and flagged below, but otherwise open to the air, with the open lavatory or general washing-place in the centre. This was the monks’ usual place of resort, except when the services in church or special duties called them elsewhere. Here, half in the open air, they read, they studied, laboured at the occupations of the scriptorium, the illuminated missal or book of the ‘Hours.’ Here was their library, and here the magister ordinis held his school for novices, a school where the instruction, however, was not, as is commonly supposed, the humanities or even divinity, but the rule of the order of St. Benedict, to be, to the monk, from the moment he had taken the vows, more than his conscience. Here in the cloister, too, the monks enjoyed such minor relaxations as fell to their lot. Here they took their ‘meridian’ or mid-day siesta; and here, for all the world like great schoolboys—whenever, that is, the prying eyes of Sacrist or Precentor were not upon them—they even indulged at times in harmless but unauthorized gossip and “snatched a fearful joy.”

Grouped round the cloister garth—their site now occupied by canons’ houses—were the domestic buildings proper: the kitchen to the west, the refectory on the south. On the east—its Norman arches still in part standing—was the Chapter House, where the Prior held a chapter daily for the regulation of the internal routine, and for the admonition or correction of offenders against the discipline. South of this, where now the Deanery stands, were the Prior’s quarters. Farther to the east were the sleeping quarters, the ‘dortour’ or common dormitory, the sick house or infirmary, and so forth; while standing by itself at some little distance in the outer court—Mirabel Close as it was called—was the Pilgrims’ hall, where the poorer pilgrims were lodged, and now almost the only part of the domestic buildings of the monastery still standing.

At the period we are speaking of monastic life had assumed a character entirely different from what it had borne in Saxon and Norman days. Poverty, obedience, chastity, and toil had been not only the motto, but actually the practice, of the earlier monk. He had not only prayed and wept, and denied himself ease and creature comforts—his life had been one unceasing round of severe bodily labour. His own efforts had sufficed for his daily wants, and in ministering to them, he had taught the savage people round him the arts of agriculture, he had reclaimed the waste lands, and had literally made the wilderness to blossom like the rose. But this active, simple phase had passed away. Monasteries like St. Swithun’s or Hyde now performed important ceremonial and social duties of an official character. The Prior of St. Swithun’s kept lordly state; the Abbot of Hyde wore a mitre. These monasteries controlled extensive interests, swayed large estates, held much church patronage, and extended generous hospitality to high and low alike. The simple organisation of earlier times now no longer sufficed, and a considerable retinue of lay brothers was considered necessary for the domestic service of the monastery, while the more purely spiritual duties alone were performed by the monks themselves. The monk was thus left free to pray and study, to perform his regular offices, and keep his ‘hours’ strictly, and only the more responsible of the domestic duties or those of supervising the several departments of activity were assigned to those who had taken the vow. The lay brethren or retainers performed the menial duties, and were so completely separate from the brethren in orders that they were even excluded from their churches. Thus the little parish church of St. Swithun perched above Kingsgate was set apart for the lay servants of the Priory, and the parish church of St. Bartholomew, Hyde, in like manner for those of Hyde Abbey. Probably few at that day could have foreseen that the churches built for the lay retainers would prove more enduring than the great monasteries themselves. Thus, spiritually speaking, the monasteries were, if not actually dead, at least moribund. Shut in from the world outside they affected less and less the stream of general spiritual life, and gradual atrophy of spiritual powers followed inevitably on the failure to exercise them.

Yet it would be a profound mistake to infer—as one easily might, particularly if one were guided by popular pictorial representations of it—that the life of the fourteenth century monk was one of ease and enjoyment. In reality it was one of severe discipline and self-repression. The eight daily services of the hours beginning at midnight with nocturnes, and ending at evening with compline, with the enforced vigils and broken periods of sleep they entailed, were but a part of the regular daily obligation. In addition there were masses to be said, study and reading in the cloister, the labours of teaching and of the scriptorium. It is a somewhat cheap sneer to set down the monk as merely indolent or self-indulgent, but his life certainly tended as a rule more to deaden than to exalt, and the monk entered the cloister only too often to discover nothing but a limited outlook and a dreary round of humdrum trivialities, instead of the religious peace and the beatific vision he had expected.

The brethren who controlled the various departments of monastic economy were termed Obedientiarii, or brethren yielding obedience to the Prior, and responsible to him for performance of their respective duties. The Prior was over all, and next to him was the Sub-prior. The church was looked after by the Sacrist and the Precentor. These regulated the services, while the latter in addition was responsible for the discipline. He was the general policeman, a kind of peripatetic conscience, imposing silence in the cloister, and checking illicit conversation, and particularly on the alert during nocturnal service, lest the burden of drowsiness should prove too heavy for any of the worshippers. Armed with a lantern he stole from brother to brother, and if any was found nodding he placed the lantern at the offender’s feet, who, thus detected and openly shamed, was required to take up, as it were, the ‘fiery cross,’ and bear it on until he should find another guilty like himself, in which case he might pass the unwelcome task on to his companion in disgrace—a kind of monastic game of touch, not without its humorous side. The manager of the estates was the Receiver or Treasurer, the chief domestic official the Hordarian or Steward, others were the Custos operum or Keeper of the Fabric, the Cellarer, the

Almoner, the Master of the Novices, or Magister ordinis, the Gardener, and so on.

A somewhat full collection of Obedientiary Rolls, or official accounts of St. Swithun’s Priory, still exists, and much valuable and interesting information has been rendered accessible to the general public by Dean Kitchen, who has edited them, and from these we can learn full details of the daily life, dietary, and operations of the monks of St. Swithun. They had two main meals a day, with certain other opportunities for minor refreshment. Bread, cheese, meat, fish, and eggs appear to have been freely provided, though it must be remembered that there were always guests as well as the monks to be catered for. On fast days ‘drylinge,’ or salt fish, and mustard figured largely, the mustard serving as a corrective to the unpalatable fare, and doubtless, too, a useful tonic to bodies which had to endure so many hours in a stone church or in an open cloister entirely unprovided with artificial means of warming. Beer was the general, and wine a rarer beverage. Relishes and extra dishes were granted from time to time, as, for instance, on festival occasions, or as a reward for special duties. To guard against chills furs were largely worn, and were indeed a heavy item of expenditure. Spices were largely used as comforts in the same way as the mustard already referred to, and to keep the monks in health the gardener was required to supply each monk with a regulation number of apples daily from Advent to Lent, doubtless, again, a wise provision at a period when vegetables were nowhere readily obtainable as at present. As an additional corrective, blood-letting, five times a year, was an habitual practice, and as this involved three days in hospital, i.e. practically three days’ holiday, it was rather looked forward to than otherwise. ‘Shaving day’ was an important event. On Maunday Thursday the monks washed each other’s feet, and once a year they had a bath. The straw for the pallets, on which they slept in the ‘dortour,’ was changed once a year.

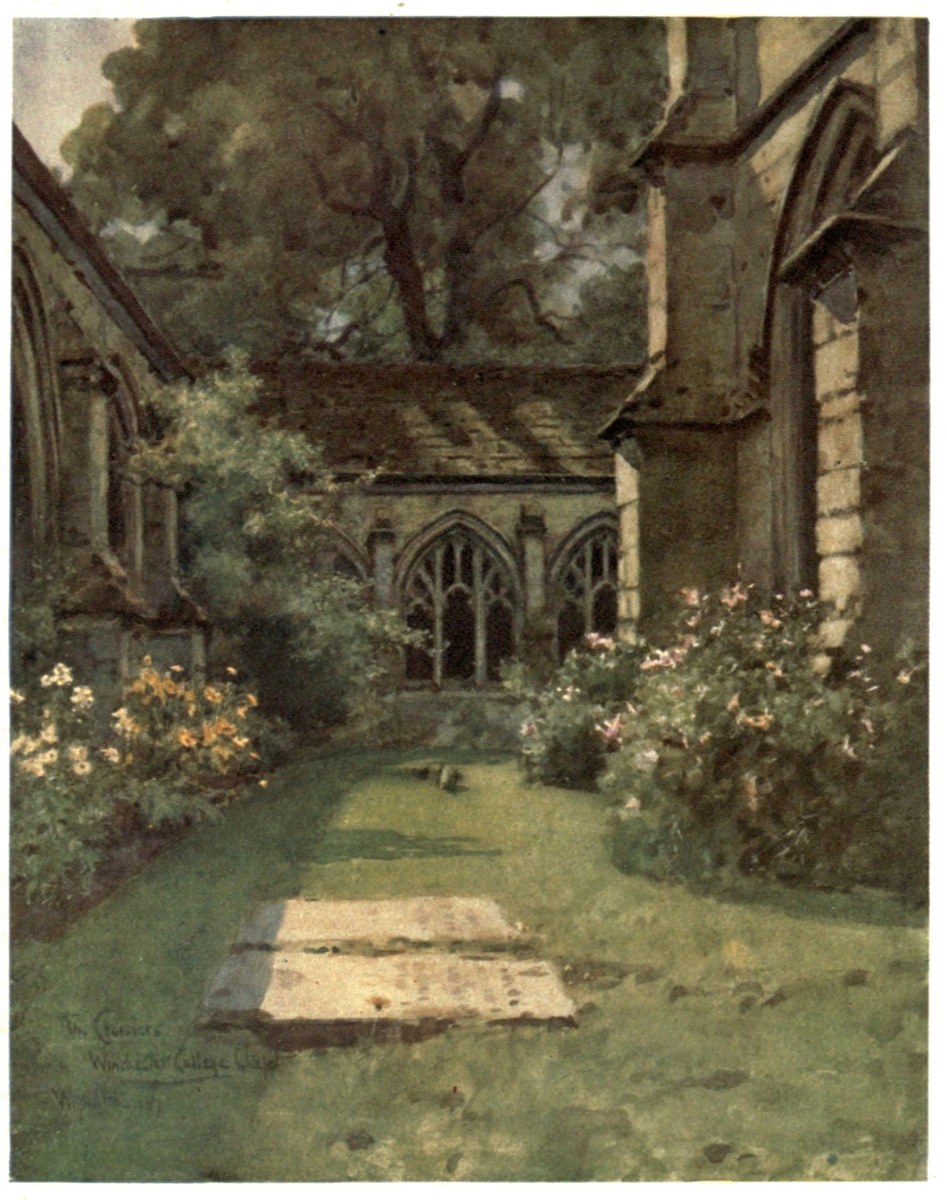

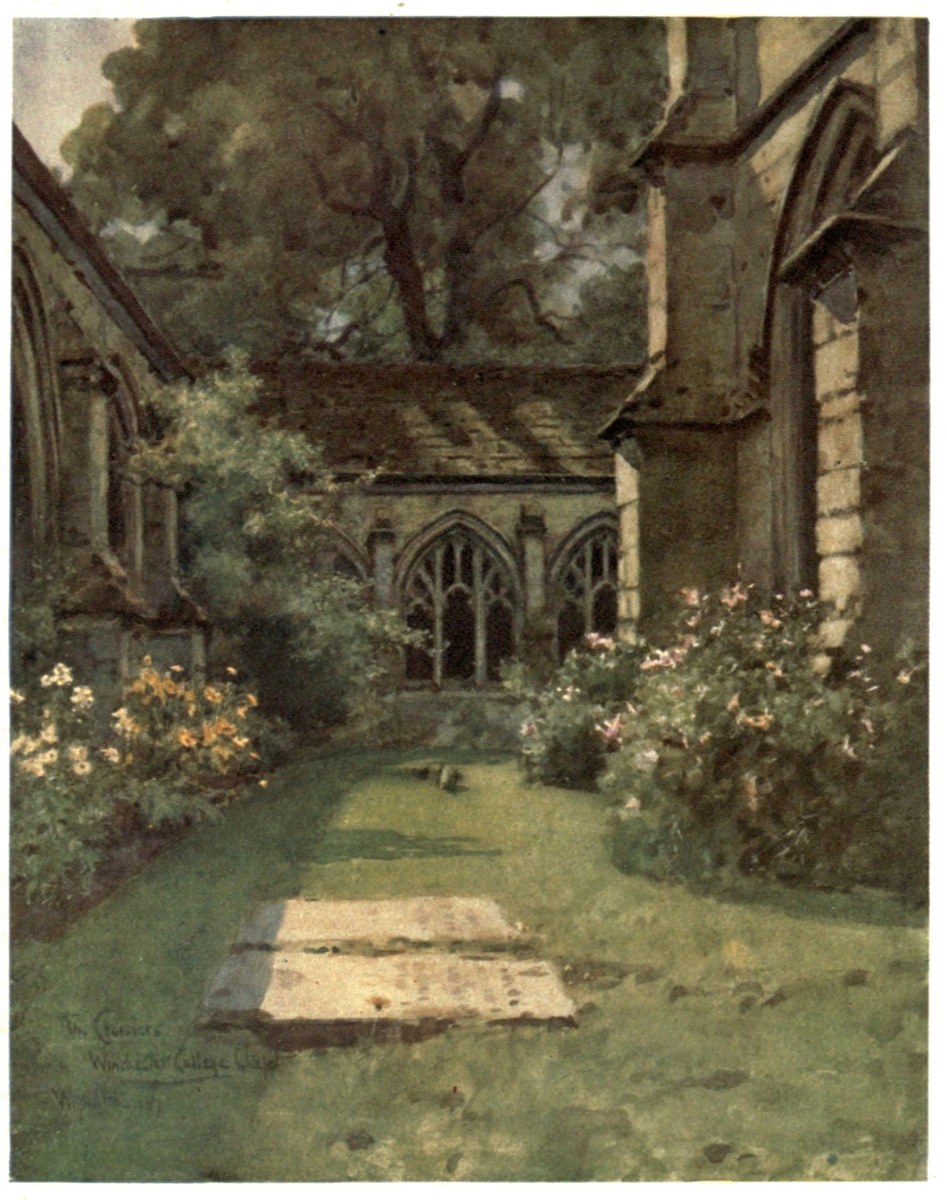

CLOISTERS AND FROMOND’S CHANTRY, WINCHESTER COLLEGE

“But let my due feet never fail

To walk the studious cloister’s pale.”

Cloisters, with Fromond’s Chantry in the centre (for College has two chapels), forms one of the most poetic spots of Winchester College.

In earlier days school was held in Cloisters during the summer months. In Cloisters the College dead lie buried. Many former scholars have cut or carved their names on the stone-work of Cloisters, among them the famous Ken, afterwards Bishop of Bath and Wells, who wrote his Manual of Prayers for the use of Winchester College Boys.

His morning hymn

“Awake, my soul, and with the sun,”

and evening hymn

“Glory to Thee, my God, this night,”

first appeared in this Manual. The inscription in Cloisters is “Thos. Ken, 1665.”

The meals were taken in silence in the refectory, while, to transpose the poet’s words,

The Reader droned from the Pulpit,

Like the murmur of many bees,

The legends of good St. Swithun

And St. Benet’s homilies.

Straw litter covered the floor, which was changed seven times a year—a higher standard of cleanliness and luxury than prevailed generally, seeing that Erasmus, 200 years later, could still complain of the filthy rush-covered floors of English houses, where bones, scraps, and ale from the table accumulated, with even less desirable kinds of dirt, and which, when it was replaced, was removed so perfunctorily that the lower layers remained undisturbed, it might be for years.

The Obedientiary Rolls, moreover, supply us with an interesting insight into the commodities in general use, and also into their prices. Reducing to modern values we find an egg and a herring practically cost then, as now, a penny apiece. Sugar existed in various forms—Sugar Scaffatyn, Sugar of Cyprus, Sugar Roset, and sweetmeats or comfits of various kinds, varying from one to several shillings a pound. Rice was largely consumed, and cost threepence a pound. ‘Coryns,’ i.e. grapes of Corinth, in other words currants, about two shillings a pound. Enormous quantities of groceries, ‘spiceries’ as they were termed, figured in the accounts, but, doubtless, largely because St. Swithun had his stall at St. Giles’s Fair, and dealt extensively in ‘spices.’

It was at Fair time that the monks had their chief holiday, and made their chief purchases. It was at the Fair that they purchased also the furs they wore so largely. On the top of the hill the Prior had his special pavilion, and kept practically open house—and doubtless the monks keenly appreciated the rare opportunity the Fair afforded for a little excursion beyond the walls. For though the Prior mingled freely with the outer world, as a great political person-age was summoned regularly to Parliament, and so forth, the monk in general but rarely left the convent gate, and saw little beyond ‘the studious cloister’s pale.’

We have fewer details of the Abbey of Hyde, just as we have fewer remains of its fabric. Such part as remains, apart from some unimportant ruins, is generally supposed to have formed part of the Tithe barn. Opposite the gateway of this—which is really an interesting piece of architectural work, unfortunately very meagre in extent,—is the Church of St. Bartholomew, Hyde, where, as already stated, the lay servants of the abbey worshipped. The squared and worked stones which are to be seen freely in the houses all round the neighbourhood are, otherwise, practically all that still remains of the great abbey.

Of its internal life we know also but little; the Liber de Hyda preserves most of its history, but we have no obedientiary rolls to chronicle its small beer. During much of its later history it had a hard struggle for existence. The Black Death all but brought ruin to it, though later on William of Wykeham did much to restore its prosperity. Its best-known abbot was Walter Fyfhyde, abbot from 1318 to 1361.

Of St. Mary’s Abbey we have fewer details still. It enjoyed a considerable revenue from the tolls, or ‘octroi,’ on merchandise which entered the city at the East Gate.

Far different from the life of monk or nun was that of the friar. In the fourteenth century he was firmly established as a Winchester institution. He was the active missioner, the revivalist, the preacher. He moved in the world, not in the cloister. He taught, he preached, he visited the slums; he was the Church-army worker or the Salvationist of his time, and if he wrought too much on the superstitious fears of his hearers, even if the relics which he permitted them to kiss were usually nothing but ‘pigges bones,’ like those of Chaucer’s ‘gentle pardonere,’ as often as not he would have been prepared to defend the fraud as a pious deception which did no harm to his listeners, while as a class the friars of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were undoubtedly the salt of the earth.

All the four orders of friars were represented in Winchester—Black Friars or Dominicans, Grey Friars or Franciscans, White Friars or Carmelites, and Austin Friars. Their quarters were generally in the slums. The name ‘Grey Friars’ still lingers in ‘The Brooks,’ and ‘The Friary’ in Southgate Road preserves the memory of the Austin Friars, though the latter, strictly speaking, were rather canons than friars proper. Between the several types of ecclesiastics deadly jealousy existed, and if monk and friar agreed at all, it was probably in a common hostility to the ordinary parochial incumbent or parish priest.

Besides these, many smaller religious or semi-religious houses of various types existed. Adjoining Wykeham’s College was the ‘Sustern Spital,’ a community of nursing sisters, fronting on to College Street; the little college of St. Elizabeth of Hungary stood near the boundary wall of ‘Mead’; and besides these were a number of others, of which Magdalene College was perhaps the chief. Mediaeval Winchester could certainly display ‘Pious Founders’ with any city of its day.

The monasteries continued to flourish in greater or less prosperity till the middle of Henry VIII.’s reign. But though the cloister monk himself might come but little in contact with the outer world, the aspects in which the monastery as a whole did so were numerous and important. Not only in its immediate vicinity did it serve as educator, general almoner, and physician, relieving want and sheltering distress, but far away also from its walls its word was law, its control all-sufficient. As landed proprietors on a widely extended scale the monasteries wielded enormous territorial influence. At their grange farms, such as the farm of the Augustinians at Silkstede, they maintained large bodies of farm hands, they reared sheep, they drove to market, they bought and sold. Nor was this all; all was fish that came into their net, and Church patronage not the least important or acceptable, so that more and more the duty of providing for the spiritual needs of neighbouring or outlying parishes fell to their share, along with the tithes or dues paid to support it, and in such cases tithe was no longer paid to the incumbent direct but to the monastery, who appointed a ‘vicar’ or deputy to carry out the spiritual duties,—a system satisfactory enough, perhaps, if faithfully followed out, but leading to every form of evil and neglect when laxity supervened, and selfishness replaced zeal; and so the system of ‘vicars’ as incumbents was inaugurated, while the frequent iteration and survival up and down the country side of such monastic addenda to the names of Hampshire towns and villages, as Itchen Abbas, Abbot’s Ann, Monk’s Sherborne, Prior’s Barton, to quote but one or two, is an eloquent testimony to the firm grasp which the monk had secured of the spiritual patrimony of the Church, and to this more than anything else is to be attributed the present poverty of the Church, and the lay patronage existing in so many rural English parishes to-day.

The closing scene in the monastic story was not, however, to be reached for some century or so longer. In Henry VIII.’s time, however, monasteries had drifted so hopelessly from the general stream of national life, that it was evident their existence could not be indefinitely prolonged on existing lines, and Wolsey, with an insight and high zeal for reform which is rarely done sufficient justice to, conceived the plan of closing them and diverting the funds thus set free to other religious and kindred purposes, the endowment of schools, colleges, etc. Henry VIII. availed himself of Wolsey’s suggestion, and Thomas Cromwell, the supple and unscrupulous instrument of an equally unscrupulous master, carried it out,—not, however, with any view of a right-minded diversion of funds set aside for religious purposes, but with the intention, barely veiled, of selfish misappropriation, and the satisfaction of personal greed, and in the general scramble for plunder, not only did the monastic property, as such, get swallowed up, but the parochial endowments—where vicars were in being, at least—were swallowed up also.

The actual closing was carried out by two commissions. In 1536 some of the smaller Winchester houses were suppressed, including the Sustern Spital and the various friaries. Then in 1537 a second commission was appointed, and the larger houses began to fall. At Hyde, Abbot Salcot proved ‘conformable’ and surrendered the abbey, and in 1538 Cromwell’s commissioners, with the notorious Thomas Wriothesley, afterwards Earl of Southampton, acting the part of ‘leading villain’ of the piece, visited it to carry out the work of demolishment. In a letter to Cromwell they thus describe their work at Hyde:—

About three o’clock (A.M.) we made an end of the shrine here at Wynchester.... We think the silver thereof will amount to near two thousand marks. Going to our beds-ward, we viewed the altar, which we purpose to bring with us. Such a piece of work it is that we think we shall not rid it, doing our best, before Monday next or Tuesday morning, which done we intend, both at Hyde and at St. Mary’s, to sweep away all the rotten bones that be called relics, which we may not omit lest it be thought that we came more for the treasure than for avoiding the abominations of idolatry.

The words are significant, and the hour 3 A.M. tells its own tale. The abbot and other inmates received pensions, very modest ones, and the manors fell into various lay hands. Wriothesley secured the lion’s share. The abbey buildings were sold for the material they were built of, and so rapidly did most of it disappear, that Leland in 1539 says in his well-known Itinerary: “In this suburb stood the great abbey of Hyde, and hath yet a parish church.” Camden, writing shortly after, speaks of the “bare site, deformed with heaps of ruins, daily dug up to burn into lime.” In 1788 what still remained of the ruins was nearly all rooted up to make a County Bridewell. No thought of Alfred, or the other mighty and illustrious dead buried within the precincts, seems to have stayed the Vandal hands; numerous relics, patens, chalices, rings were found. A slab of stone bearing Alfred’s name was taken away, and is still preserved at Corby, in Cumberland. It was not part of Alfred’s tomb, as it bears the date 891. So far all attempts to locate the position of Alfred’s tomb have been unsuccessful. Like Moses of old, “no man knoweth of his sepulchre unto this day.”

The suppression of St. Swithun’s had results less drastic. Hyde Abbey was simply swallowed up in the catastrophe. St. Swithun’s was transformed into the capitular body of the Cathedral, the Prior, Sub-prior, and monks disappeared, and in their places succeeded the Dean, the Chapter, and Canons of Winchester.

The new establishment thus formed was at first composed of the Dean, twelve prebendaries, and six minor canons. The Prior, William Kingsmill, proved ‘very conformable,’ and became the first Dean of the new collegiate body. The commissioners, here as at Hyde, stripped the Cathedral of its ornaments. The silver shrine of St. Swithun disappeared, and various other shrines, and the glorious treasures of gold and silver, and precious stones, the gifts of Cnut, Bishop Stigand, and many another pious donor, which had graced the high altar, were all swept away by the greedy hands of the spoilers.

The domestic buildings have almost all now disappeared. The chapter-house was pulled down in 1570 by Bishop Horne, largely for the sake of the leaden roof; and the cloisters later on suffered a similar fate. Part of one of the convent kitchens remains in one of the houses at the west side of the cloister garth, and some portions of the domestic buildings still remain in the Deanery, but practically all connected with the domestic life of the monastery has now disappeared. In 1632 Bishop Curle opened a passage, now called ‘The Slype,’ by cutting through the great buttress on the south side, and so converted the cloister garth into a thoroughfare. Two curious Latin anagrams cut on the west front of the Cathedral and on the wall adjoining commemorate this. But the Priory, thus transformed, gained rather than lost in usefulness. Much of the property was indeed seized by the king, but the Dean and Chapter have remained otherwise in full possession of the powers and privileges granted to them, while the fuller and less restricted range of activity has rendered the Cathedral the centre of ecclesiastical life and of extended usefulness, far exceeding what the Priory in its later days ever succeeded or perhaps ever aimed at securing.

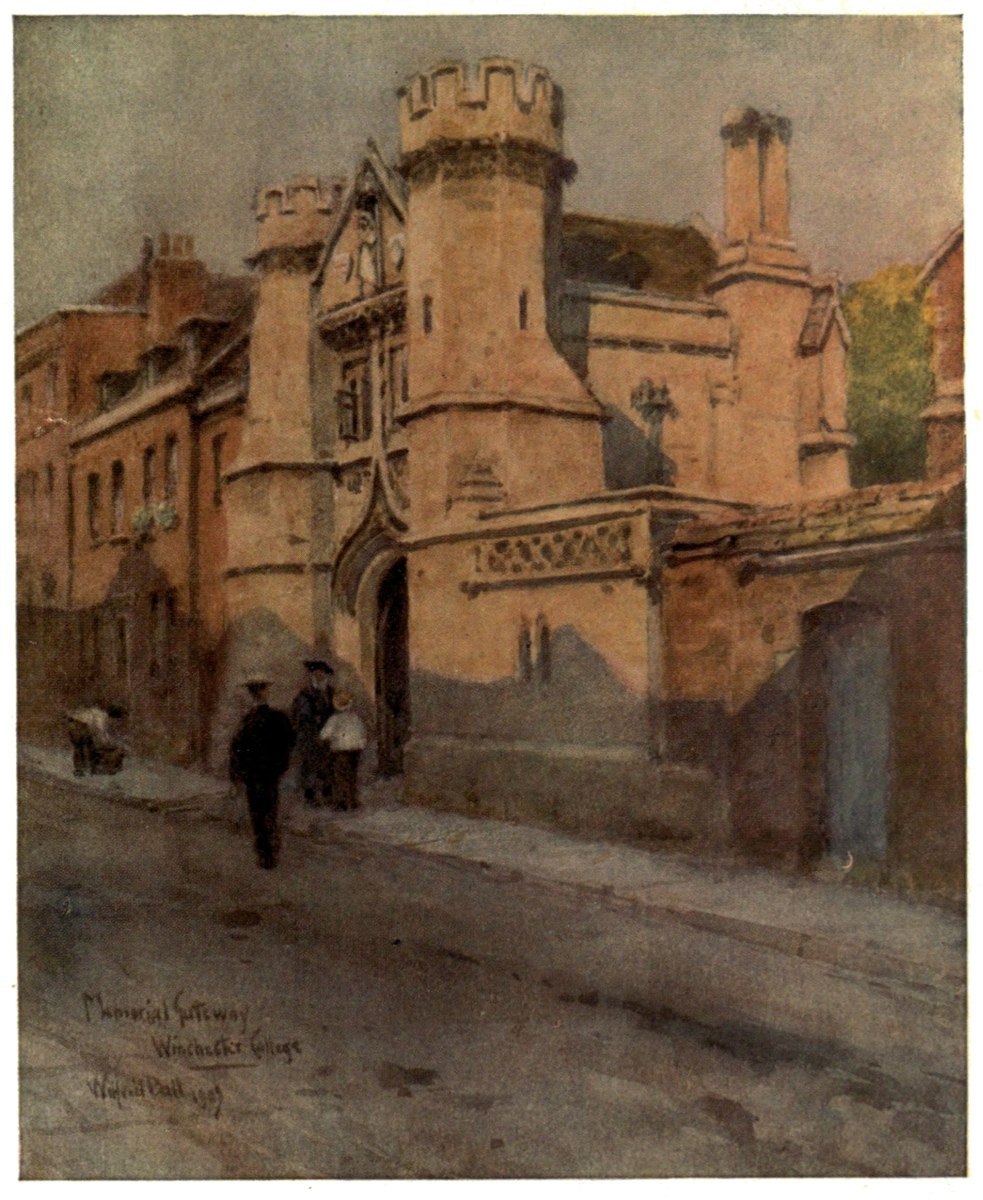

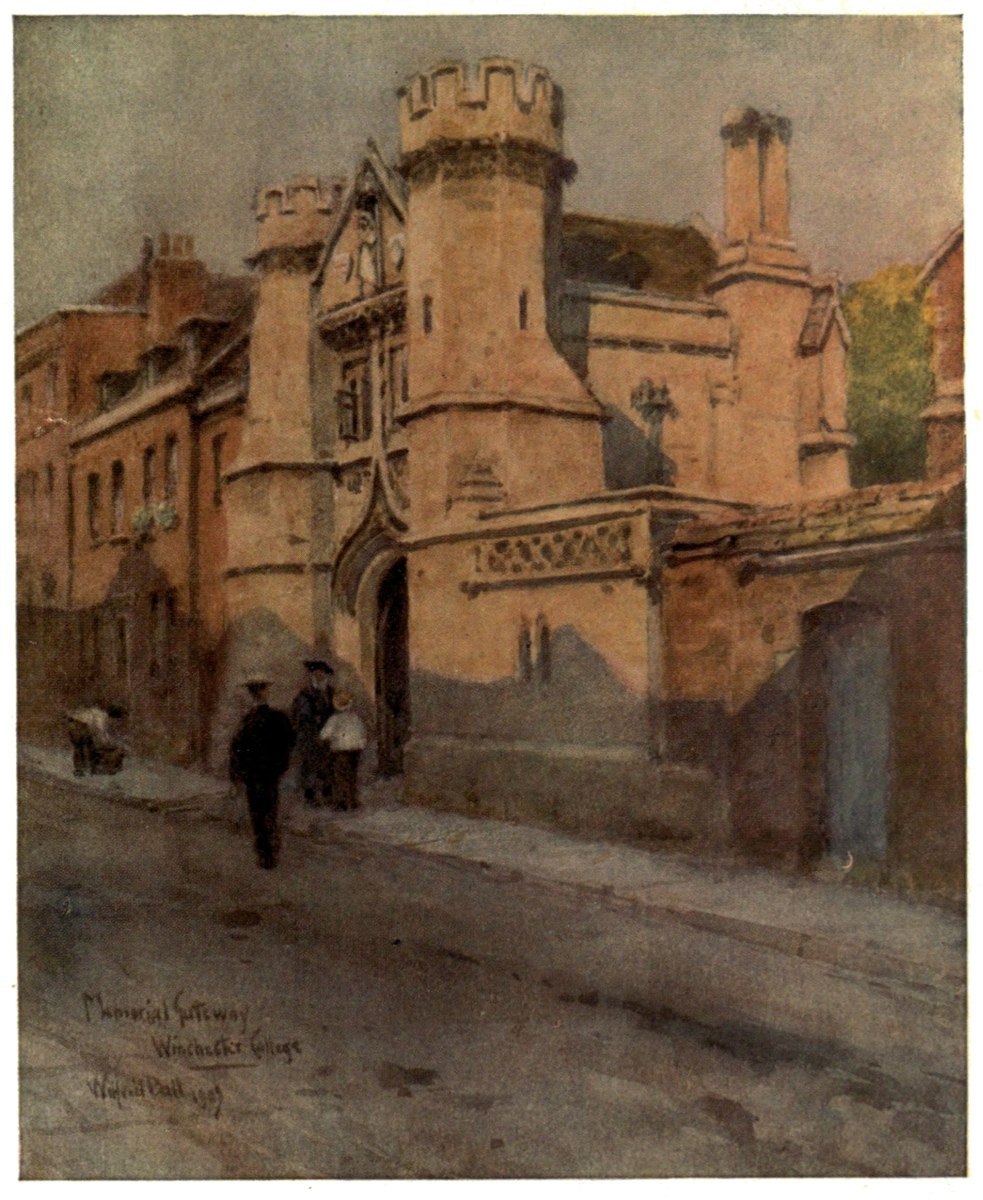

MEMORIAL GATEWAY, WINCHESTER COLLEGE

The Memorial Gateway, opening on to Kingsgate Street, was erected recently in memory of Wykehamists who fell in the South African War.

The suppression of St. Swithun’s was the first in point of time; later on, in 1538, Hyde was dissolved; in 1539, St. Mary’s Abbey—Nunna Mynstre—founded by Alswitha, Queen of Alfred the Great, suffered a like doom. St. Elizabeth’s College lasted a few years longer, and was finally sold to Winchester College in 1547, and the buildings pulled down. The college luckily survived the visitation, so, also, equally fortunately, did St. Cross and St. John’s Hospital, and these remain in continued and more extended usefulness till the present day.