CHAPTER XVI

THE CATHEDRAL

Sermons in Stones.

TO deal adequately with Winchester Cathedral would be almost to write the history of England, a task manifestly impossible within the limits of such a work as this. For the Cathedral is not merely a building, but a veritable history in stone, and that not a history—as historic buildings very often are—of a community which has raised but a small eddy in the waters of national life, but of one which has profoundly affected the fortunes of the nation during almost every period of its existence. It is safe to say that scarcely a single storm of national strife has burst upon the land without leaving in some way an impress upon these grey stone walls, and during a period of many centuries there was scarcely one single actor of eminence in the national drama who did not leave, in some form or other, a record imperishably graven here behind him. Not only have these stones witnessed the coronations of kings—the baptisms, marriages, and burials of princes—the consecration of bishops, and many another ceremony of high national significance, but they enshrine within their circuit the sacred dust of generations of the great departed, subject and king, soldier and priest, statesman and prelate; they are a great national Valhalla with which no other in the land save Westminster Abbey can claim to compare. As the preceding pages have shown, a Christian cathedral has existed continuously on the present site since the days of Kynegils and Kenwalh, in the 7th century. Bishop Swithun and Bishop Æthelwold successively added to or rebuilt large portions of the fabric, but the only Saxon work now remaining is in the crypt and foundations. The pillars and arches are splendidly massive and curiously fashioned, and show that Æthelwold’s work was solidly constructed. The Cathedral, as we see it to-day, is the Norman and Angevin Cathedral—the cathedral of Walkelyn and of Godfrey de Lucy, transformed in later Plantagenet days by Edyngton, Wykeham, and Beaufort, and adorned by Silkstede, Fox, and many others. Walkelyn’s Cathedral was a typical Norman building, and the disposition of its parts reflected a symbolism as well as a harmony. The central truths of Christian doctrine, those of the Trinity and of the redemption, were beautifully symbolised in the three-fold repetition of nave, triforium, and clerestory in the elevation, and of nave, choir, and transepts disposed in the form of a cross in the ground plan. The arches and pillars are characteristic examples of the Norman style—semicircular arches springing from heavy, cushion-shaped capitals surmounting the strong circular pillars. The general effect of the interior, though heavy, was one of impressiveness and dignity, as can be well seen from the transepts, which remain for all practical purposes unaltered from their original form, or better still from the interior of Chichester Cathedral of to-day. It reflected alike calmness, dignity, and strength—the dignity of a strength conscious of a burden indeed, but self-reliant and adequate to the task. It is no light burden that those giant pillars are bearing, nor do they support it joyously or even with ease: each one is rather an Atlas, bearing his load strongly and uncomplainingly, but needing to put forth all his powers in the effort.

Godfrey de Lucy, Bishop in Richard I.’s time, extended the church eastwards by adding the retro-choir with its beautiful Early English arcading, graceful columns, and lancet windows,—an extension which, owing to the insufficient foundation on which he built, is in large measure responsible for the insecure condition of the fabric to-day. This we will revert to later on in the chapter. Godfrey de Lucy’s object was to afford space for the ever-increasing numbers of pilgrims who crowded to Winchester to see the shrine of St. Swithun, but who in other respects were unwelcome guests. His extension eastward afforded every facility to admit the pilgrims in to view the shrine, without giving them access to the choir, nave, or domestic parts of the Priory. In Edward III.’s reign came the transformation of the nave and aisles—a daring work commenced by Bishop Edyngton, and completed by William of Wykeham, almost equal in magnitude to the reconstruction of the fabric itself. Edyngton’s work may be seen in the aisle windows at the extreme west of the building; Wykeham’s, which is lighter and more graceful, fills the rest of the nave. The general result has been to impart to the interior gracefulness and lightness. The columns on either side of the choir steps, which were left partly unaltered, show us in some measure how the change was effected, partly by pulling down and rebuilding, partly by cutting away from the face of the columns. The triforium was removed bodily, and the triple row of Norman arches thrown together into a single range of light, lofty, and graceful Perpendicular-Gothic arches, surmounted by smaller Perpendicular windows serving as clerestory. Triforium proper no longer exists, but its place is taken by a continuous narrow balcony running along both sides of the nave. The impressiveness and beauty of the effect thus produced it is impossible to describe. As you enter at the west end the majesty of the whole at once silences and uplifts you—a forest almost of lofty shafts and pillars rising unbroken and towering overhead, where they branch out and interlace in the beautiful intricacy of the fan-tracery of the roof.

It is not without appropriateness that Wykeham and Edyngton both lie buried here in the beautiful chantry chapels which they respectively erected between the pillars on the south side of the nave.

The work of transformation from Norman to Perpendicular was continued through the choir and presbytery aisles by Beaufort and others, and later bishops extended the building eastward beyond the limits of Godfrey de Lucy’s work. The three chapels at the east end, Orleton’s Chapel, commonly spoken of as the Chapel of the Guardian Angels, Langton’s Chapel, and the Lady Chapel, contain much interesting and varied work.

In one sense the retro-choir is, architecturally speaking, the most interesting part of the Cathedral. It presents wonderful variety, and contains specimens of practically every stage of architectural development since de Lucy’s day. But it must be confessed that the general effect is rather a confused medley of seemingly haphazard or tentative reconstructions, and the piecemeal character of the separate parts deprives it to a large extent of the dignity and completeness of a harmonious whole. Nowhere is this exemplified better than in the three east windows of the south transept—all altered from the original Norman windows, and each entirely different in character from its neighbours. Yet this very want of harmony is strangely eloquent. Winchester Cathedral, and its east end more particularly, is not an architect’s cathedral, so to speak—one complete harmonious design like Salisbury; rather is it a document in stone—a deed to which many participants have affixed their sign-manual, each in his characteristic writing, and bearing the direct impress of his personality.

Yet fascinating as its architectural features are, they are dwarfed and unimportant beside the wealth of historical association that lies locked up within these walls as in a treasure-chest.

Of the many great and solemn ceremonials which these walls have witnessed—such indeed, to mention one or two only, as the second coronation of Richard Cœur-de-Lion, the baptism of Henry VII.’s son, Arthur of Winchester, Prince of Wales, the marriage of Henry IV. with his second wife Joan of Navarre, and that of Mary Tudor, Queen of England, to Philip of Spain—we will not now speak in detail. Rather will we concentrate our attention on the historic and architectural monuments which meet our eye almost wherever we turn, and among this wealth of historical and architectural treasures three may be singled out for special notice—the chantry chapels, the reredos, and the mortuary chests. The chantry chapels are gems of beauty and of interest, enshrining the mortal remains as well as the memories of six notable men,—Edyngton, Wykeham, Beaufort, Waynflete, Fox, and Gardiner. Wykeham’s chantry is almost daringly constructed out of and between two of the great pillars of the nave. The memories of the three chantry monks who served it in Wykeham’s lifetime are preserved by three charming miniature figures placed in effigy at Wykeham’s feet. The chantries of Beaufort, Waynflete, Fox, and Gardiner are east of the choir. Beaufort’s chantry, less beautiful perhaps architecturally, is wonderfully suggestive. How eloquently the recumbent effigy seems to recall the strong features of the man who desired power so earnestly, and could dare greatly in the effort to possess it—those rigid hands now clasped meekly in prayer betoken a humility and repose which their owner when in life probably never enjoyed, nor it may be even desired. Waynflete, again, had a notable career. Headmaster of Winchester, he was chosen by Henry VI. as first headmaster of his new foundation of Eton, and shortly after from headmaster became Provost, from which position he rose to become Bishop of Winchester. Waynflete founded Magdalen College, Oxford; and Magdalen College has but recently been discharging a pious duty by undertaking the work needed for the preservation of her founder’s chantry. With Waynflete, Wykeham, and Foxe (founder of Corpus), all buried in these chantries, Winchester might almost claim to have founded Oxford herself. Architecturally each chantry marks a step forward in the development of style, and registers the successive stages in the rise, culmination, decline, and death of Perpendicular Gothic.

Of the great altar-screen we have already spoken. Here we have Perpendicular Gothic at its very best, rich in effort, yet in perfect taste, without the least suggestion of the florid or the bizarre—the detail so varied, the execution so delicate. The statuary is modern, but is beautifully executed and in perfect keeping—a somewhat unusual excellence—with the original work. It would be hard to meet with so illustrative and remarkable a series of Christian saints and examples as are here shown in effigy grouped round the Saviour’s figure—the four archangels, the Virgin and St. John, St. Paul and St. Peter, doctors like Jerome, teachers like Ambrose, Christian missionaries like Birinus, bishops like Swithun, Æthelwold, Wykeham, and Wolsey. Among sovereigns we have Egbert, Alfred, Cnut, and Queen Victoria. Among the others of note are Earl Godwine, Izaak Walton, Ken and Keble. Many of these lie actually buried within the Cathedral walls, and nearly all left their mark inseparably and honourably stamped, alike on the national, as on the city history.

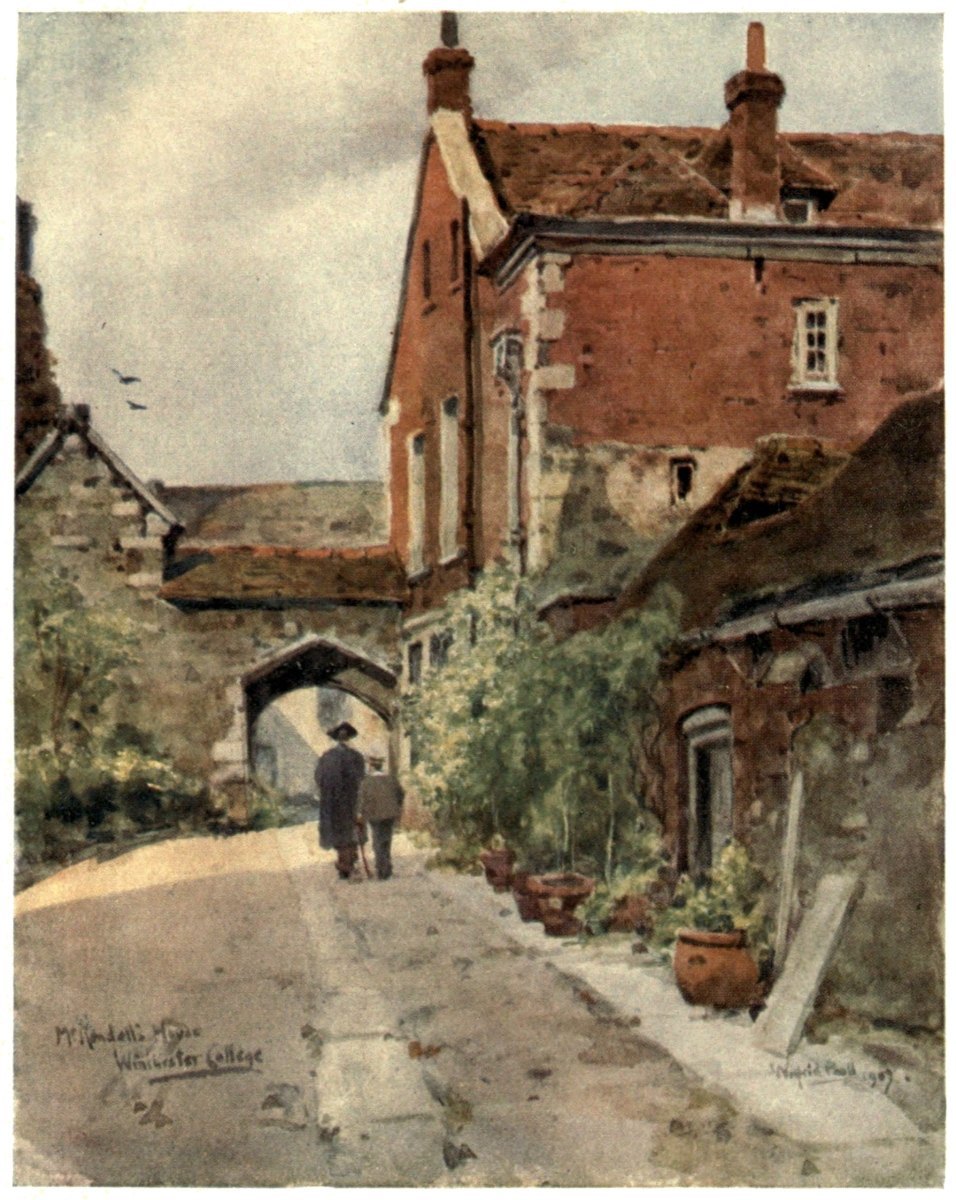

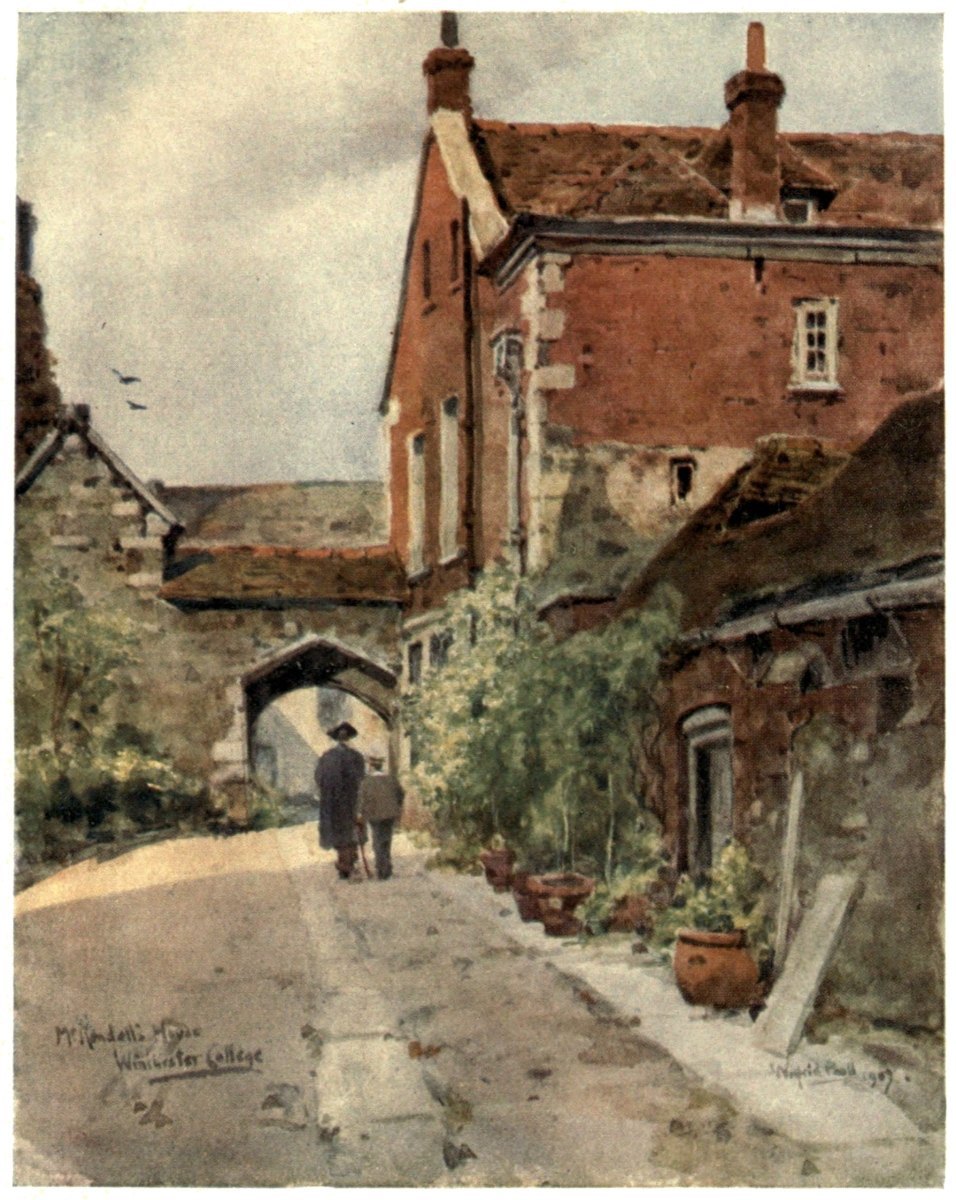

SECOND MASTER’S HOUSE, WINCHESTER COLLEGE

Wykeham’s ‘children,’ the seventy scholars that is, are still lodged in College, as they have been from the first, under the charge of the second master, whose house lies between Outer Gateway and Chamber Court, over which latter some of the windows look out.

Of all the historical memorials, however, none is capable of so profoundly stirring the imagination or arresting the attention as the six beautiful mortuary chests placed above the side screens of the choir. Think what associations the inscriptions on these recall. Early Wessex chieftains, as Kynegils and Kenwalh: kings of Wessex, when Wessex was supreme over all England, as Egbert and Æthelwulf: the union of Saxon and Dane, as personified by Cnut and Queen Emma; the Norman tyrant as represented by Rufus. Not even in Westminster Abbey itself can names such as these be read. And close at hand are other significant names too: Harthacnut: Richard, son of the Conqueror, fated, like his brother Rufus, to meet a violent death in the New Forest, but otherwise unknown to history: Duke Beorn, murdered at sea by Sweyn, son of Earl Godwine. These and other striking names can be found graven on the stone-work which carries the mortuary chests above.

Of former bishops of Winchester the majority are buried here. Some of these—and among them some of the most famous—have no visible sign to mark their tomb; these include such names as Birinus, Swithun, Æthelwold, Walkelyn, Henry of Blois. There are many others too over whom we should like to linger: Peter de Rupibus, for instance, the evil genius of Henry III.’s reign, and Ethelmar or Aymer, the absentee bishop, who died in Paris, but desired his heart to be placed in a casket for interment in the Cathedral, though when alive his affections seem to have been centred anywhere but here. His monument is more picturesque than his life was edifying. He is represented in effigy in the attitude of prayer, and holding his heart between his folded hands. In striking contrast to these are monuments to Bishops Morley, Hoadley, Samuel Wilberforce, and Harold Brown.

Over the remaining monuments, and there are many of very great interest, we cannot linger. Flaxman is represented by a bas-relief of Dr. Warton, famous in his day as headmaster of the College, seated in his magisterial chair, with a group of college boys ‘up to books.’ The details of schoolboy attire are curious and interesting. Appealing to a wider circle are two flat slabs of stone, one in Prior Silkstede’s Chapel, one in the north aisle. The former bears the name Izaak Walton, the latter Jane Austen. Truly Winchester Cathedral is a city of the mighty dead.

In addition to the monuments there are many other features of great attractiveness. Prior Silkstede’s carved wooden pulpit, the quaint old font curiously carved in black stone, said to have been brought to Winchester by Henry of Blois, and the miserere seats in the choir stalls are among these. The Cathedral library, too, is of rare interest. The wonderful Illuminated Vulgate, with its almost romantic history, and numerous early Saxon charters are preserved here, along with Cathedral and city records of great historical value.

The exterior of the Cathedral presents less interest. It is grand and striking, but hardly beautiful. The West front is flat and featureless, the long straight roof of the nave is monotonous. The east end, with its varied work and the huge Norman transepts, is by far the finest portion. Taken as a whole the general effect is extremely dignified and impressive, and the surroundings are entirely in keeping.

As you pass down the beautiful lime avenue, or cross the grass to the west and north, the quiet dignity and repose impress you with an influence deeper than mere beauty, and the Cathedral Close, with its Jacobean and Georgian houses, is equally serene, dignified, and attractive. The Deanery is interesting, particularly the Early English work in the portico, and the beautiful green sward in Mirabel Close, with the Pilgrims’ Hall to the east, and Cheyne Court with its open-timbered and gabled houses, all both alike quiet, stately, and harmonious. A rare place this Close, with associations too of its own. Even nowadays it possesses its ghost—a female figure robed and veiled like a nun—which persons still living will describe to you, for they have seen it themselves, they declare, and heard its ghostly footfall echoing as it has paced before them on the flags. Nor is the word ‘Close’ a word only. Still every night the gate is religiously locked at the stroke of ten, after which none may enter or depart save by favour of the Close porter, the lineal successor of the ‘proud portér’ so prominent in Early English ballad poetry.

Before leaving the Cathedral we must say a few words about the operations for the repair of the fabric to which reference has already been made.

The insecurity of a large part of the fabric is due mainly to the foundation on which Godfrey de Lucy built when he extended the Cathedral towards the east. To do this he had to build out over an area of peaty and water-logged land, wherein to reach a solid foundation it was necessary to go down through successive layers of marl and gravel and peat, to a considerable depth, varying from 16 to 24 feet. As this involved working under water, and as the task of dealing with water under foundations was beyond the skill of builders of the time, de Lucy made an artificial foundation of beech logs, or beech trunks rather, laid horizontally one over the other and kept in place with piles, with the result that a progressive subsidence has occurred, mainly, but not entirely, at the east end, causing walls to bulge and crack, and fissures to appear, until the present degree of insecurity has been reached. Thus it has been not a question of restoration, but of preservation, and the work has been taken in hand not a moment too soon.

The present operations have consisted, in the main, of systematic underpinning of the walls and buttresses, and as much of the work has had to be carried out under 10 feet or so of water, a diver has been employed to lay down concrete in section after section at the base of the new foundations, the water being afterwards temporarily drawn off by the help of powerful pumps, to enable the work of underpinning to go on. The employment of divers to lay foundations for a building 800 years old would appear a fantastic absurdity, transcending the wildest stretch of imaginative invention. Winchester Cathedral has actually realised it.

Unfortunately, the securing of the southern aisle of the nave may demand an addition,—not merely underpinning, but the construction of buttresses. But these, although novel, will be no more foreign to the general design than were the corresponding buttresses which Wykeham added to the north aisle; and these, with the further addition of the great tie-rods inserted at various spots in the transepts and retro-choir, will, it is hoped, give the Cathedral a stability which will ensure its preservation for centuries more. The operations, so novel in character, so daring in conception, so extensive in scale, are yet unfinished, and while some £90,000 has been already expended on the work, something like another £12,000 is still needed for its completion.