CHAPTER XVIII

WOLVESEY—ST. CROSS—THE CASTLE HALL—THE ROUND TABLE

And for great Arthur’s seat ould Winchester preferres,

Whose ould Round Table yet she vaunteth to be hers.

DRAYTON’S Polyolbion.

FROM College one turns naturally to Wolvesey—Wolvesey with its wonderful grey stone walls, its memories of Saxon and Norman, Plantagenet and Stuart times. Here Alfred kept his Court, with all the learned men of his time around him; here the English Chronicle was first compiled; and here, above that very Wolvesey wall, it may be, the Danish pirates captured in the Solent were hanged—as has been already related—in retributive justice. But the big blocks of ruin in Wolvesey Mead are of later date; they recall to us the career of that notable figure among the Bishops of Winchester, Henry of Blois, King Stephen’s brother, bishop from 1129 to 1171—the masterful man, devoted churchman, and scheming politician, whose story has been somewhat fully related in Chapter VIII. To strengthen himself he fortified his dwelling at Wolvesey with an ‘adulterine’ castle—for he built here without royal warrant, as he built his castles elsewhere at Bishop’s Waltham and at Hursley,—and he sided alternately with Stephen and Empress Matilda in the civil war, as circumstances dictated. And so it befell that Winchester itself became divided into rival camps; Matilda’s forces held the Royal Castle and the Bishop held Wolvesey, and, here within his defences, now in ruins, the Bishop stood the siege valiantly. Ultimately peace was made, and Winchester saw Prince Henry make joyful entry into her ruined streets and ratify the compact. His later years were passed in works of peace and beneficence, and for these he will always be most gratefully remembered.

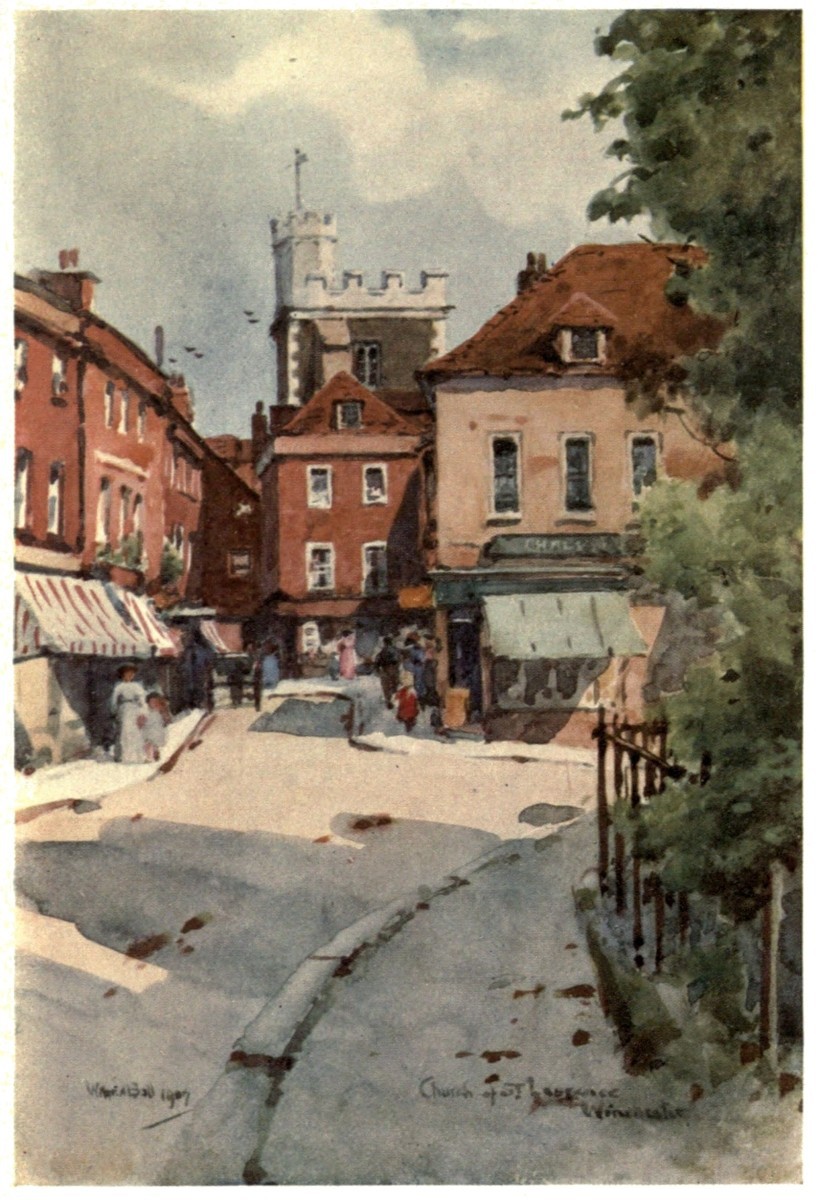

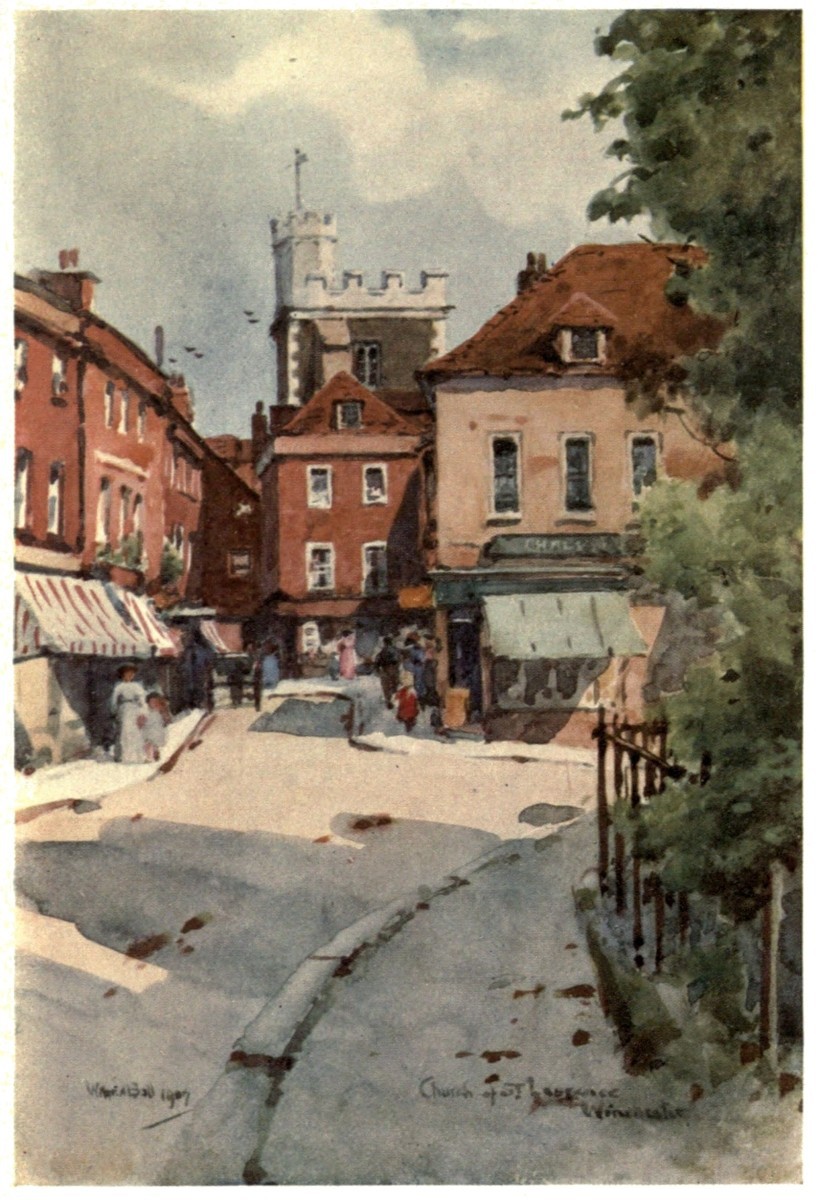

CHURCH OF ST. LAWRENCE, WINCHESTER

A small but extremely interesting parish church in ‘The Square,’ of which practically all the exterior, save the Western Doorway and the Tower, is hidden from sight by the houses and shops hemming it in on all sides. Every Bishop of Winchester on being installed proceeds in solemn procession from the Cathedral to St. Lawrence Church to ring the bell—a picturesque survival of feudal days. ‘The Square’ marks the site of a palace built for his own occupation by William the Conqueror.

He built the Hospital of St. Cross, a permanent refuge for thirteen poor brethren, and a house of daily entertainment for the poor and needy outside its walls. He placed his foundation of St. Cross under the protection of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, an Order specially devoted to guarding the welfare of pilgrims and wayfarers. And so the Brethren of St. Cross still wear to-day the eight-pointed cross of the Order and the black gown which distinguished the Knights Hospitallers, and the wayfarer’s dole of bread and beer may still be asked for and obtained at its hospitable gates. Advancement, personal power, and political ascendancy, all these Bishop Henry desired for himself, strove for, won and lost in turn. St. Cross retains its vitality still,—such is the perennial virtue of unselfish kindliness and beneficence.

Though its fortifications were dismantled, Wolvesey remained the residence of the Bishops of Winchester for many centuries after Henry de Blois. Here, on March 28, 1394, in the presence chamber of Wolvesey, William of Wykeham received the warden, John Morys, and the seventy scholars of his Newe College of St. Marie, and gave them his blessing as they set out in solemn procession to enter into occupation of their newly erected premises. In the Civil War, after Cromwell’s capture of the city, the old Bishop’s Castle was finally dismantled.

Present-day Wolvesey Palace stands on your left as you enter from College Street with the Norman ruins and the old Tilt yard in front of it and on your right. Bishop Morley, the friend of Ken and Izaak Walton, erected it. But Wolvesey and Farnham together proved too heavy an episcopal burden, and later bishops have preferred to reside at Farnham. So Wolvesey ceased to be the Bishop of Winchester’s official residence, and the greater part of Morley’s building was pulled down by Bishop North at the end of the eighteenth century. The growing need for the division of the diocese makes it quite possible, however, that the Bishops of Winchester may again be residing in Wolvesey Palace, as their predecessors did for so many hundreds of years.

Wykeham’s College, ‘the Newe Saint Marie College of Wynchester,’ is but a stone’s-throw from Wolvesey. The story of the College has been fully dealt with in a former chapter, and so, now, as we pass along College

Street from Wolvesey, our thoughts may well turn to a house on the left adjoining College, with memories of a different kind, those of Jane Austen. A tablet over the door recalls the fact of Jane Austen’s death within its walls in 1817. She had removed here from her home at Chawton, near Alton, in hope of recovery under the medical treatment which Winchester could afford her. But the hope was vain. She lies buried in the north aisle of the Cathedral nave. We know her now as among the rarest and most charming of women novelists. Of her we shall speak again in the chapter on ‘Winchester in Literature.’

Some half mile or so south of College, beyond New Meads and the meadows by the river—those meadows from which the tower and pinnacles of College Chapel form so poetic a picture as they mingle with the trees around, and the Cathedral behind—lies St. Cross, a foundation which has undergone many vicissitudes and been at various times “much abused” (see pp. 188, 189), but which has happily now for many years past been rescued from the spoiler and restored to the full exercise of generous beneficence. Of its foundation by Henry of Blois we have already spoken, but in its associations another historic name figures, of equal prominence with Bishop Henry’s—that of Beaufort, Bishop and Cardinal in Henry VI.’s reign. Beaufort was a second founder, and the domestic buildings and the fine gateway are his work. Along with the Brethren with black gown and silver cross will be seen some wearing a mulberry gown, with the Beaufort Rose as emblem; these are Brethren of the order Beaufort founded—the Order of Noble Poverty. St. Cross is not a place to describe at all in words; its traditions, its characteristic customs, its general atmosphere belong to it and to it alone; to appreciate it it must be felt. Peaceful and dignified, with the clear transparent waters of Itchen flowing quietly by at its feet, there is no place in Winchester, or indeed anywhere else, where the sense of hallowed charm, of serenity, of contentment, and of rest seems quite so natural and so pervading as here.

Wherever else we turn in Winchester we find some treasure or other over which to linger. On the high ground forming the south-west angle of the city there is the County Hall, last surviving relic of the great royal castle, which William of Normandy first erected and which his successors added to. For some six hundred years that great keep, with its heavy battlements and frowning bastions, scowled down upon the city and overawed its burghers. Yet, grim and all but impregnable as those ‘rude ribs’ might seem to be, more than one assailant found means to penetrate within. Here, in 1140, Matilda the Empress, besieged by Stephen’s Queen, was forced by hunger to abandon resistance, and to seek safety by stealth and stratagem in a hasty and disastrous flight—her power of effective resistance broken finally and for ever. Here, in 1645, flushed with victory from Naseby field, came Cromwell, and, after nine days of hot cannonade, compelled the surrender of the citadel—a surrender which he followed up by ordering the castle to be ‘slighted,’ i.e. razed to the ground.

The present Castle Hall was erected by a Winchester monarch—Henry III., Henry of Winchester. Here again the sense of the historic past swells and surges round you. It is almost a revelation in history to walk round it and follow out in detail the memories of those whose history is personally connected with it, their names and arms all emblazoned in the stained glass which fills the lights on either side. Local feeling has been just recently somewhat deeply stirred by the removal within the Hall of Gilbert’s well-known bronze statue of Queen Victoria, formerly placed in the Abbey grounds—a removal which has evoked a very unfortunate controversy, and as to the wisdom of which considerable cleavage of opinion exists. But whatever view be taken of this, as to the impressiveness of the great Hall, within and without, or the story it has to tell, no two opinions can be held. The grand interior with its splendid columns speaks of great assemblies within its walls; of Parliaments such as the one held here as early as 1265, within a year of the death of the great De Montfort, the ‘inventor,’ so to speak, of the representative assembly; of State ceremonial displays such as when Henry V. received the French ambassadors here, a few days only before the Agincourt expedition sailed—as when Henry VII. celebrated the birth of his first-born, Arthur of Winchester, Prince of Wales, and as when Henry VIII. received and fêted the great Emperor Charles V., the

Charlemagne of his day; of State Trials such as that which unjustly condemned Sir Walter Raleigh; of the Bloody Assize and the horror of the judicial murder of Dame Alicia Lisle; while the most characteristic touch perhaps of all is given by the quaint relic hanging on the western wall, the so-called King Arthur’s Round Table. A curious relic indeed this latter, and an ancient one, possibly 700 years old. We shall hardly accept it, as Henry VIII. and his royal Spanish guest did, as the actual table at which King Arthur and his knights used to seat themselves, even though we may read their names—Sir Launcelot, Sir Galahallt, Sir Bedivere, Sir Kay—inscribed upon its margin. Rather does it recall to us those quaintly attractive, uncritical mediaeval days, when historical perspective was unknown, that glorious age when “Once upon a time” almost satisfied the yearnings of the historical instinct. Yet one may question whether we are really better off, because for us King Arthur’s Round Table has no existence and Arthur himself is lost in the strange background of

Moving faces and of waving hands,

that weird labyrinth where history and legend, myth and romance, are so strangely and inextricably interwoven; and one turns away baffled and reluctant from many and many an old-world story, and many and many an old-world relic such as this, with the sense of something like a lost inheritance.

So sad, so fresh, the days that are no more.

There is, however, little real excuse for these unavailing regrets in Winchester, for she above all places has store of real history—and such history, too—enough and to spare.

Here, for instance, in the West Gate adjoining the Castle Hall, and in the Obelisk just beyond the circuit of the old walls, this vividness of history meets us again. Formerly the West Gate was a blockhouse as much as a gate. You can still see where the portcullis worked up and down, and look down from the battlements of the roof through the machicolated openings which enabled defenders to meet assailants with molten lead and kindred compliments. Later on it was a prison. On the walls of the splendid old chamber above the gateway we can see elaborate designs carved out by one poor prisoner after another, to while away the tedium and to help him to forget the miseries of his imprisonment. Now the West Gate is a museum with a collection of rare local interest: early weights and measures of the days when Winchester could still impose its standards upon others, weapons and armour, the gibbet of the executioner, and the axe of the headsman. But strong for defence as the West Gate and city wall were, the Obelisk beyond recalls to us one foe whom no bar could exclude, no bolt restrain; for though in 1666 Winchester was straitly shut up like Jericho of old, and none went out and none came in, that grim and relentless assailant, the Plague, passed all barriers unchallenged, and Winchester became as a city of the dead. Then—for none dared approach—the country people held their market without and chaffered for their wares at safe distance with the men upon the wall, and the Obelisk, erected in 1759, serves to commemorate the spot where marketing was done for Winchester citizens under such tragic conditions. Happily, plague has disappeared from our midst for some 250 years. In mediaeval days, right on indeed from 1348, the year of the Black Death, plague was all too common a visitant. The sister societies of Natives and Aliens still survive in Winchester, to carry on the work of relieving widows and orphans, first begun when plague laid its hand so heavily on the city in the ‘Annus Mirabilis’ and left so many widows and orphans to relieve.

Full of interest as the West Gate is, it leaves a sense of regret behind when we remember that it is the only one remaining of the four principal gateways which the city once possessed. The artificial and curiously warped ideas of taste and sentiment which characterised the mid-Georgian period were responsible for a wholesale destruction of Old Winchester architectural treasures. Three historic gateways, the ruins of Hyde Abbey, the tomb of Alfred the Great, Bishop Morley’s Palace of Wolvesey, all these and others suffered destruction, partial or complete. The City Cross itself was condemned to removal, but popular indignation, ever ready to express itself in Winchester as vigorously, even in modern days, as it was in earlier days of Saxon and Dane, when popular clamour round the hustings was the due and only expression of law, could not be restrained, and the City Cross was left undisturbed. Nor did the West Gate escape except by accident. The great room over the gateway was at that time held as an annexe to a public-house adjoining, and so the West Gate was spared merely in order that Winchester citizens might the better enjoy their ‘cakes and ale.’ History teaches us to be grateful at times to strange benefactors. To many, with the present trend of social and political thought, the sentiment Das Gasthaus als Freund will come almost as a shock, yet here in Winchester we are confronted by the curious paradox, that while water has sapped the stability of the Cathedral, that of the West Gate has been secured by beer.

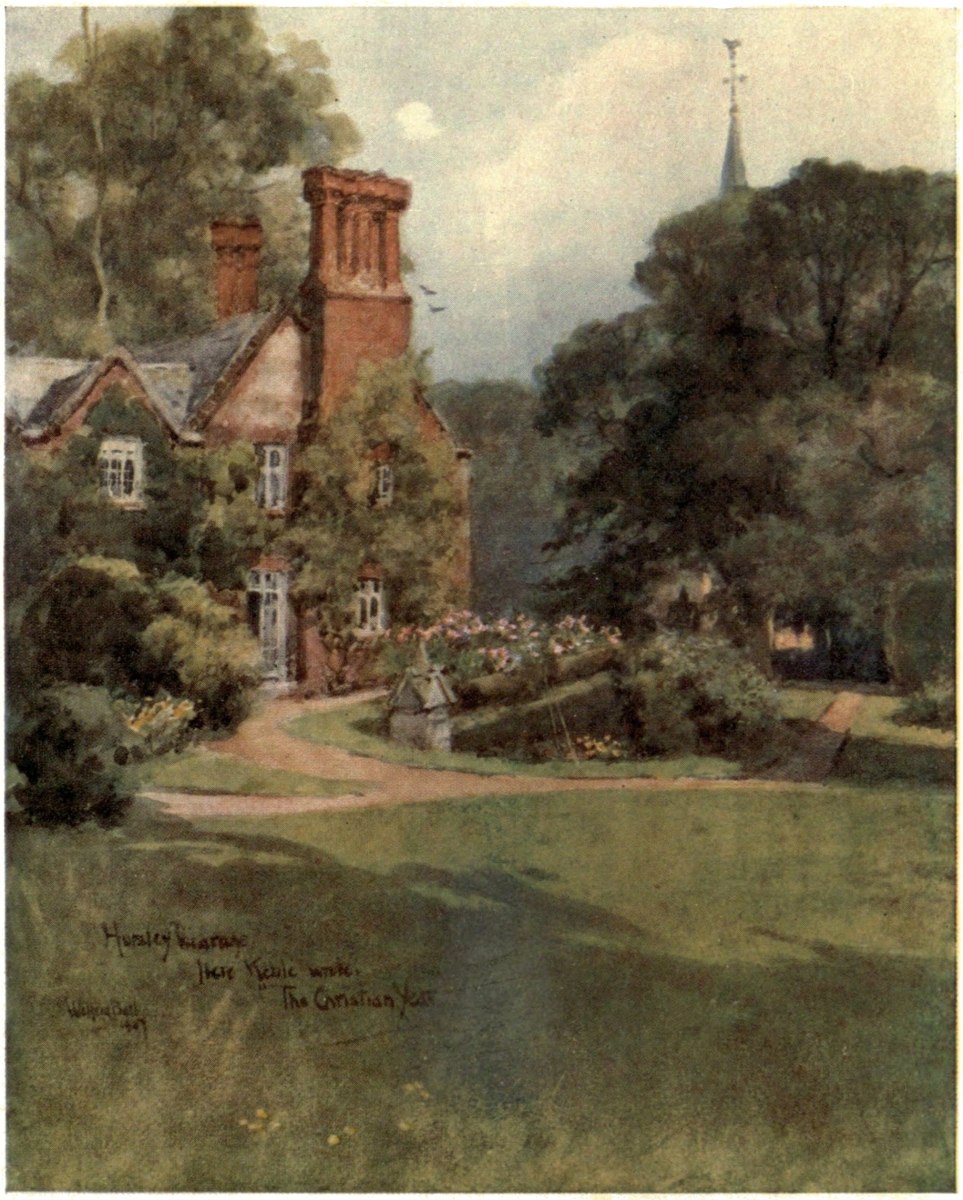

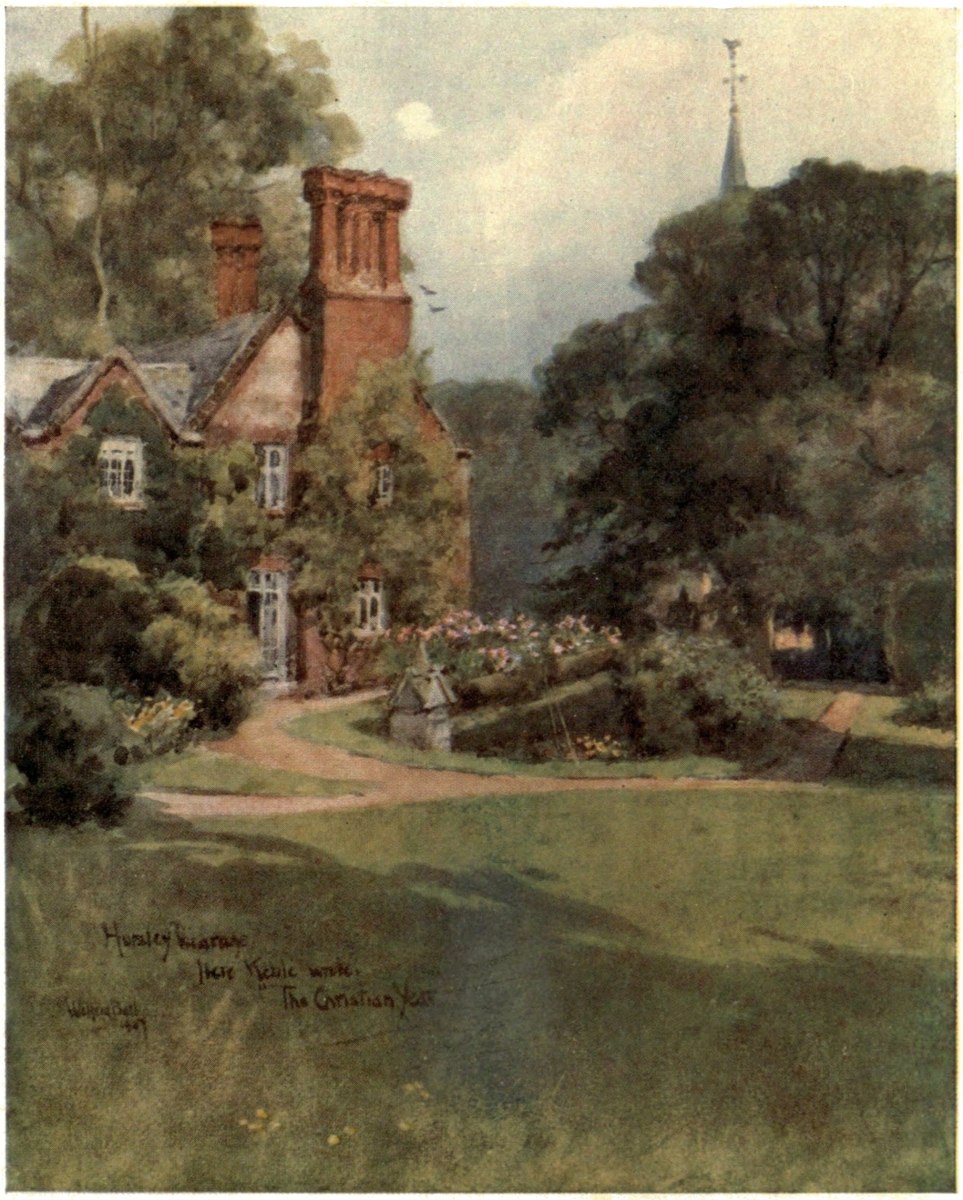

HURSLEY VICARAGE

Hursley, five miles from Winchester, is the centre of ‘Kebleland.’ Here John Keble was parish priest for thirty-one years. Hursley Church was practically rebuilt from the profits of the Christian Year, and Keble and his wife lie buried in Hursley churchyard close to the porch on the southern side.

The village has memories of Richard Cromwell, and there is a fine historical monument to the Cromwell family in the tower of Hursley Church.

Municipal life in Winchester forms another chapter full of interest. Of her early ‘gilds,’ dating back perhaps to days before Alfred, of the Chepemanesela, the Chenicteshalla, the Hantachenesla, and other vaguely indicated centres of civic organisation, where, in Henry I.’s time, the citizens in their various grades assembled to ‘drink their gild,’ we have already spoken. Her roll of mayors claims to begin with Florence de Lunn in 1184. Whatever antiquity the Mayoralty can justly claim—for Florence de Lunn can hardly be treated quite seriously—her corporate history is full and varied.

The new Guildhall in the Broadway, some thirty years old only, which has replaced the old Guildhall in the High Street, possesses an interesting collection of civic portraits, along with corporation plate, municipal archives, and much wealth of historic raw material.

The finest of these pictures, King Charles II.’s portrait, painted by Lely, and presented by the Merry Monarch himself to the city, represents, perhaps, the only return with which the loyalty of the citizens towards the house of Stuart was rewarded. They lent King Charles I. £1000, they melted their private plate, valued at £300, and their city plate, valued at £58 more, to help to fill his empty coffers when the Civil War was raging. Old Bishop Morley, whose memories centre closest round present-day Wolvesey and Farnham, and Bishop Hoadly of the Queen Anne period, are among the more interesting of the personalities whose effigies are here displayed.

Many, indeed, are the interesting memories which Winchester preserves of the Merry Monarch and his Court; of Nell Gwynn and of the valiant stand made against her by Prebendary Ken; of Sir Christopher Wren and the palace he commenced to build for his royal master on the site of the castle razed by Cromwell—a great and ambitious project never completed, but which, under the name of the King’s House, served for many years as the military headquarters of the city till a great fire swept it away in 1894, to make room for the present barracks, erected, soon afterwards, on very nearly the same site.

Another interesting Guildhall portrait is that of Edward Cole, Mayor in 1597, a patriotic citizen who himself subscribed £50—a large sum for one man in those days—towards the Queen’s war fund in days of the Armada, and a ‘gubernator’ some years later of Christes Hospitall, Winchester, founded, by Peter

Symonds, in 1607 alike for the maintenance of the aged and the education of the young—a foundation possessing a delightful old Jacobean building, just beyond the Close wall, out of which has grown, almost within the last decade, on a wide and open site on the outskirts of the city, a rapidly developing school of modern type, where the ‘children’ of Peter Symonds, in largely increased numbers, receive a far wider education than was possible when he first called them into existence.

His will is a curious and characteristic document. It occupied an enormous number of folios. Blue Coat schoolboys, practically until the removal of the school to Horsham, showed respect to his memory by some sixty of their number attending a special Good Friday Service at the church of All Hallows, Lombard Street, at which sixpences and raisins were distributed, in accordance with his will; and his Winchester scholars and Brethren keep his memory by an annual procession to service at the Cathedral on St. Peter’s Day, with a special sermon and quaint ceremonial observance.

Such are some of the matters of interest, small and great, which meet you wherever you turn in Winchester—everywhere there is some genius loci, some cricket installed, and chirping on the hearth. Here it is a quaint tavern-sign such as you can read on the outskirts. As you leave the city you read the legend “Last Out,” as you approach from without you read “First In.” Or it is a name of some street—Jewry Street, for instance, recalling the times when, as already narrated, the Jews formed a powerful element in the commercial prosperity of the city, and had a Ghetto here—or Staple Garden, reminiscent of the great Wool Hall, where the ‘Tron’ or weighing-machine of the Wool Staple was kept, when Winchester was the mart where the wool trade of the south of England centred. And here and there are darker and more sombre recollections, such as the tablet outside the City Museum serves to remind us of the moving tragedy of the execution of Dame Alicia Lisle in September 1685, on a spot in the open roadway, in front of what then was the Market House. Then, too, there are glorious old houses, Tudor and mediaeval, like God Begot House and the so-called Cheesehill Old Rectory, and the delightful houses erected by Sir Christopher Wren himself—those inhabited now by Dr. England and Captain Crawford in Southgate Street for instance, and the house in St. Peter’s Street erected for the Duchess of Portsmouth, of unpleasant memory. These are merely random examples of the kind of interest which Winchester presents to those who wander through her streets with eyes to see and ears to hear. For the casual visitor Winchester has much to offer; for the student of history she has more; but her wealth of treasure can only be apprehended adequately by those who are privileged to dwell within her charmed circle, for her harvest of attraction is too wide to be garnered save by those who bring extended opportunity as well as love and reverence to the task.