CHAPTER XIX

WINCHESTER IN LITERATURE

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s eye

Clothes them with shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

IT is always a pleasing occupation to follow out the associations of human fancy which often invest persons and places with an interest, and indeed a romantic charm, to which the cold-eyed historian or dryasdust critic is entirely unresponsive, and if Winchester as it first appeared to us, as we looked down from the brow of St. Giles’s Hill, seemed to throb with the life and interest of a departed age, and of historical personages long since passed away, so too we shall find that it possesses associations of the purely literary type, not indeed fit to challenge comparison with the glorious pageantry of its historic past which we have attempted, all too inadequately, to present upon our stage, but not unworthy to be chronicled and to be included in her volume of romance and recollection. Her points of contact with literature have been many, and yet it would be wrong to describe her as a literary city. No poet of note, no great writer, has, in recent days at all events, claimed her as parent; her acquaintance has been rather with literary persons than with literature itself, for though she has attracted many to make her in some form or other their theme, but little of real weight in any but ancient literature has first seen the light beneath her auspices. For all this she has, in literature as in life, her story to tell, and that an ancient one.

The first literary associations of Winchester are, as is but natural, historical ones, and the first mention of her in literature is found in Bede, who records for us, among other scanty details, her name, ‘Venta, quae a gente Saxonum Ventanceastir appellatur’; she next appears in a full flood of glory, the seat of the learned and literary court of Alfred, from which he gave the world the treasures of his literary efforts—the Consolations of Boëthius, Gregory’s Pastoral Care, Orosius, and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, all rendered into the vernacular, and more important far than all of these, the great thesaurus of early national history, the English Chronicle, the history of which we have already related, and from which we have quoted so constantly in our earlier chapters, to be followed by the equally momentous Domesday Book—curious as it may seem to include this among literary productions. Following from this we have a wide and almost bewildering series of chroniclers, historians, and annalists, some of whom, like William of Malmesbury, Henry Knighton, and Matthew Paris, record details of her career incidentally as general items in the history of the land, while others, like Precentor Wulfstan and the annalists of Ealden Mynstre and Newan Mynstre, laboured at Winchester in their respective scriptoria, producing not merely wonderful works like the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold and the Golden Book of Edgar, but local histories in goodly store, the Hyde Liber Vitae and Liber de Hyda, and the later monkish annals of Plantagenet days—Rudborne’s Major Historia Wintoniae, the anonymously written Annales de Wintonia, and others. Prominent among these various chroniclers was Geoffrey of Monmouth, who, romancist and fabricator as he was, has yet rendered valuable service by preserving the British legends as they survived among the Brythonic folk, and has given us—and let us be duly grateful—the Arthurian legend in all its suggestive elusiveness and mystery, centring round Winchester and Silchester, with Arthur the Christian King, Merlin the Mage, Dubric the High Saint, and many another—a legend which passed through many languages and many lands, gathering store of added marvels on the way, the customary guerdon of such literary wanderings, to reappear in strange unwonted guises, as in Layamond’s Brut and the Morte d’Arthur of Malorie. And the legendary lore of Winchester is far from being her least attractive literary asset: we have dealt with this subject fairly fully already—some may perhaps deem too fully,—yet is not legend but the alter ego of history, and are not myth and legend, sober fact and imaginative creation, after all merely the multicoloured strata in the complete rainbow of presentment of vital truth, passing and repassing each into other by nice gradation and imperceptible advance? But all these are but prehistoric as it were, when English as a language was not, and monastic Latin and Anglo-Saxon the muddy media of literary communication.

The Winchester stream in English literature begins to flow at first with feeble current—a distich or so of uncouth verse, or a casual reference, as in Piers Plowman, Leland, Camden, or elsewhere. Drayton, in his Polyolbion, has some twenty lines or so on the Itchen, referring to the Round Table of Arthur at Winchester, and the towns on her course, speaking of

... that wondrous Pond whence she derives her head,

And places by the way, by which shee’s honoured,

(Old Winchester, that stands neere in her middle way,

And Hampton, at her fall, into the Solent Sea),

and Ken and Walton, in later Stuart days, come upon the scene. Ken is a real Winchester possession—educated at Winchester College, and later on, Prebendary of the Cathedral, he wrote his well-known and still widely-used Manual of Prayer for the use of the scholars of Winchester College, and his Morning and Evening Hymns breathe the same spirit of the inner religious life afterwards so beautifully reflected in Keble’s Christian Year. His preferment to the see of Bath and Wells arose too out of his sturdy refusal to countenance the Merry Monarch’s irregular life, for he refused to let Mistress Eleanor Gwynne have the use of his house to lodge in, a refusal which angered the king at the time, but conciliated his respect, for on the bishopric falling vacant he declared that none should have it but the “good little man who refused his lodging to poor Nelly.” Izaak Walton, Ken’s relative, made Winchester his residence during the closing years of his long life—a man of culture and some literary pretension, apart altogether from his immortal Compleat Angler, for his lives of Donne and Herbert attained to some celebrity; tradition connects a certain summer-house by the stream in the Deanery garden with him and his fishing, and in several places in his Compleat Angler he makes allusion to our Winchester streams, showing that he had ofttimes baited his angle by one or other of its waters. Peace to his soul—he rests in the Cathedral, in Silkstede’s Chapel, and the verses over his tomb, though devoid of all literary merit, are said to have been written by Ken his kinsman.

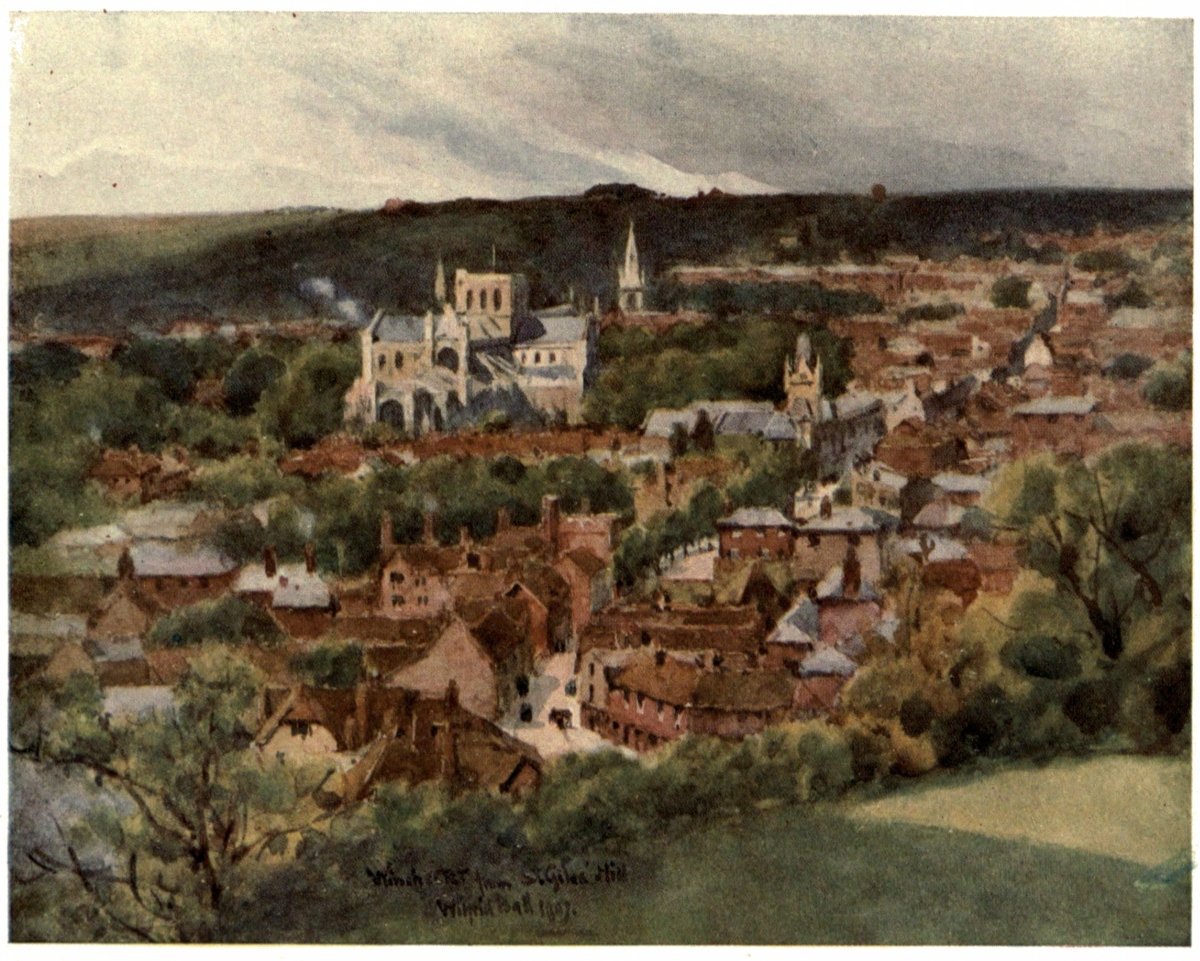

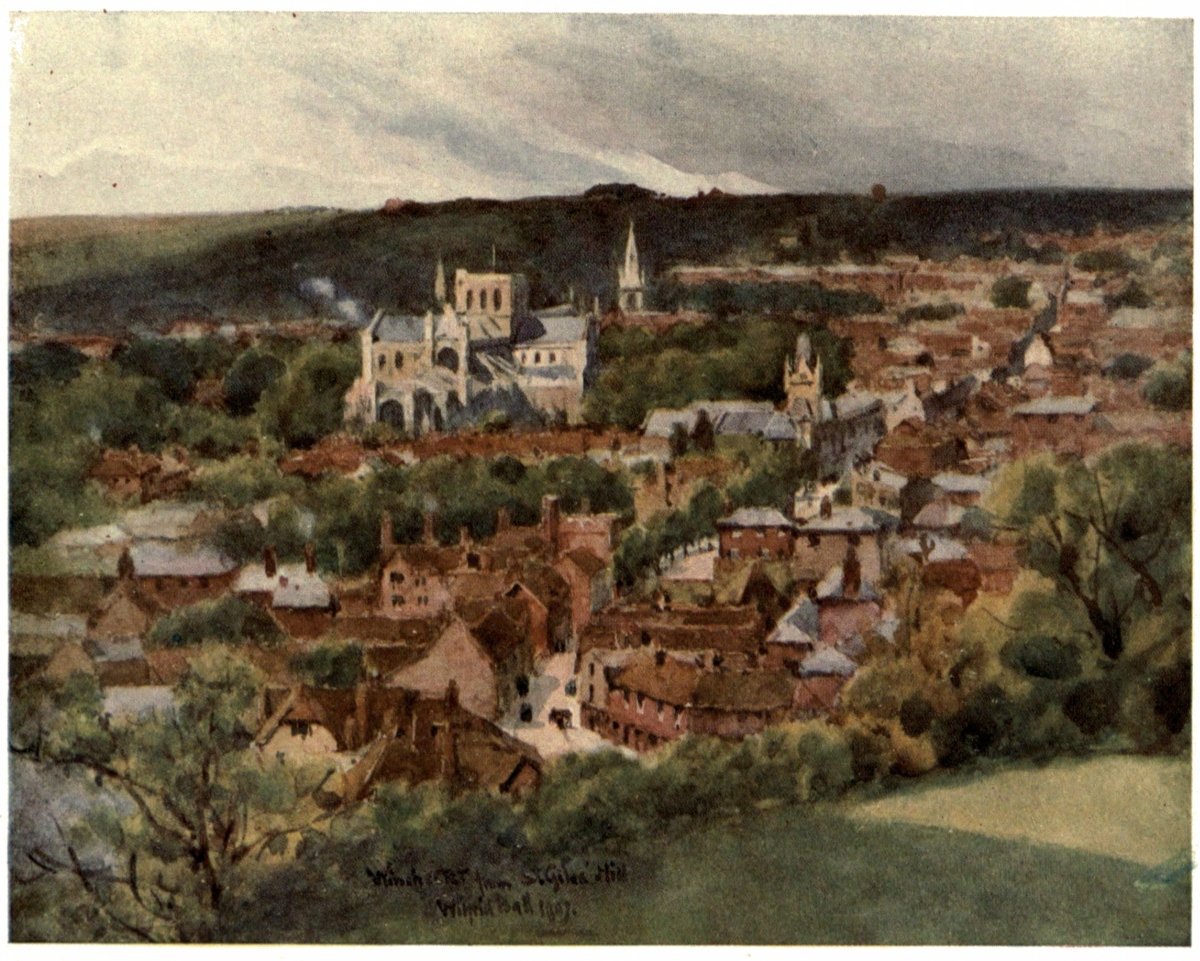

WINCHESTER FROM ST. GILES’S HILL

From St. Giles’s Hill, where in mediaeval days the world-famous Fair of St. Egidius or St. Giles was held, an unequalled view of Winchester city can be obtained. The Cathedral, Wolvesey, the College, the Guildhall, the High Street, the Alfred Statue, the Old Guildhall, the Westgate, can all be seen. The dark clump of trees on the sky-line is the so-called Oliver’s Battery.

Our next possession is a greater name—and that, moreover, a Hampshire, though not in any real sense a Winchester one—the Hampshire novelist, the most charming and natural of women writers, Jane Austen. Here in the early days of 1817, when a deadly and insidious malady had attacked her, she came with her sister Cassandra to lodge in a house in College Street, occupied then by a Mrs. David, in the vain hope that Winchester medical skill might restore her strength.

The following letter from her pen,[3] written at this period, reveals the characteristic espièglerie of the writer, which not even advancing weakness could disarm or subdue.

MRS. DAVID’S, COLLEGE STREET, WINTON,

TUESDAY, MAY 27TH.

There is no better way, my dearest E., of thanking you for your affectionate concern for me during my illness than by telling you myself, as soon as possible, that I continue to get better. I will not boast of my handwriting—neither that nor my face have yet recovered their proper beauty; but in other respects I gain strength very fast; am now out of bed from 9 in the morning to 10 at night; upon the sofa, it is true, but I eat my meals with Aunt Cassandra in a rational way, and can employ myself, and walk from one room to another. Mr. Lyford says he will cure me, and if he fails I shall draw up a memorial and lay it before the Dean and Chapter, and have no doubt of redress from that pious, learned, and disinterested body. Our lodgings are very comfortable. We have a neat little drawing-room with a bow window, overlooking Dr. Gabell’s garden.... On Thursday, which is a confirmation and a holiday, we are to get Charles [a relative—then a boy at the College] out to breakfast. We have had but one visit from him, poor fellow, as he is in sick-room, but he hopes to be out to-night.... God bless you, my dear E. If ever you are ill, may you be as tenderly nursed as I have been. May the same blessed alleviations of anxious, sympathising friends be yours; and may you possess, as I dare say you will, the greatest blessing of all, in the consciousness of not being unworthy of their love. I could not feel this.—Your very affectionate aunt,

J. A.

Poor Jane Austen, the rally was but a momentary one, and an untimely death cut short her career just as she was developing to her best work. She is buried in the Cathedral, where, curiously, the flat stone slab over her body speaks eloquently of her benevolence of heart, sweetness of temper, and Christian patience and hope, but not one word of her literary skill or claims as an authoress—the only reference to these is in the indirect phrase “the extraordinary endowments of her mind.” So little was her right place in literature then realized, that some among her friends saw her appearance as a novelist rather with concern than with approval, and her literary ventures were even referred to apologetically. Posterity has amply atoned for this neglect: the Cathedral possesses two memorials of her—a brass and a stained-glass window; and she has long since been admitted to the high measure of appreciation to which her naturalness and sincerity justly entitle her. The Dr. Gabell referred to in the letter was, of course, the well-known Dr. Gabell, headmaster of the College, mentioned in the previous chapter, a characteristic figure famous in his day, a picture of whom, had she been spared, she might perhaps have left us, limned in her own nervous and inimitable manner; but, alas! it was not to be. Fortunately the house she occupied is known, and a commemorative tablet, placed over the door, records appropriately her sojourn there and her untimely death.

Following close upon Jane Austen came another, with a name ever to be honoured in song—a summer migrant merely, it is true, or rather an autumn one,—whose light was destined to be shortly afterwards suddenly extinguished also. John Keats, the poet, who came here in August 1819 from Shanklin, where “Keats’s Green” preserves his memory, for a visit of some two months’ duration—“the last good days of his life.” Several considerations dictated his visit to Winchester, among others, the desire to have access to a good library, a desire destined, quite unaccountably, to disappointment. His letters written from Winchester are full and charming literary productions: he describes the ‘maiden-ladylike gentility’ of her streets; the door-steps always ‘fresh from the flannel’—the knockers with a staid, serious, and almost awful quietness about them; the High Street as quiet as a lamb, the door-knockers ‘dieted to three raps per diem’;—in such happy, delicate phrases he hits off the Winchester of the day. Of the place itself he gives us interesting touches: the air on one of its downs is ‘worth sixpence a pint’; the beautiful streams full of trout delight him; the Cathedral, fourteen centuries old, enchants his imagination; while the foundation of St. Cross he finds to be greatly abused.

Where he lodged we know not, dearly as we should like to—we can only form such conclusions as the following clues[4] point to:

I take a walk every day for an hour before dinner, and this is generally my walk. I go out the back gate across one street into the Cathedral yard, which is always interesting; there I pass under the trees along a paved path, pass the beautiful front of the Cathedral, turn to the left under a stone doorway—then I am on the other side of the building, which leaving behind me, I pass on through two College-like squares, seemingly built for the dwelling-place of Deacons and Prebendaries, furnished with grass and shaded with trees; then I pass through one of the old city gates and then you are in one College Street, through which I pass, and at the end thereof crossing some meadows, and at last a country alley of gardens, I arrive at the foundation of St. Cross, which is a very interesting old place, both for its Gothic tower and Alms square and also for the appropriation of its rich rents to a relation of the Bishop of Winchester. Then I pass over St. Cross meadows till you come to the most beautifully clear river. Now this is only one mile of my walk.[5]

Another clue, which locates the house very close to the High Street, if not in it, is given by the following:

We heard distinctly a noise patting down the High Street as of a walking cane of the good old Dowager breed, and a little minute after we heard a less voice observe, “What a noise the ferril made—it must be loose.”[6]

Winchester streets are less staid and genteel now, and the High Street would hardly echo responsive to such repressed sounds to-day.

Two months only the visit lasted, months of tense compression and rich utterance of song. Hyperion (which he never finished), Lamia, The Eve of St. Agnes, La Belle Dame sans Merci—all these in one form or other came under his pen for completion or revision, while his Ode to Autumn, the most perfect of all his odes, was wholly a Winchester production inspired by his circumstances and surroundings. The German poet might almost have had Keats prophetically before him when he sang:

Singst du nicht dein ganzes Leben,

Sing doch in der Jugend Drang!

Nur im Blüthenmond erheben

Nachtigallen ihren Sang.

E’en though after years be silent,

Sing while youthful passions throng,

Only in the fervid spring-time

Nightingales pour forth their song.

But no after years, alas! were to succeed, and Keats’s fervid ‘Blüthenmond’ was all his allotted span. Winchester is happy in the memory of his eventful connection with her, brief in time though it was.

Our next name is Thackeray, who seems to have loved to locate his scenes in our city and neighbourhood, though in general his references have too little local colour to permit of identification—assuming, that is, that any such local image was really intended.

Vanity Fair and Esmond are full of local allusions; Sir Pitt Crawley, for instance, would appear to derive his names from Pitt and Crawley, two villages close to Winchester; and in Esmond, Hampshire allusions, tantalisingly veiled, it is true, seem to meet and to baffle you everywhere. It seems impossible to avoid identifying Castlewood, with its ruined house battered down by Cromwell, and the Bell Inn with Basing House and Basingstoke; and while Alton, Alresford, and Crawley are all mentioned, it is round Winchester that interest centres and perplexes most. Where else in literature is a scene so inimitably conjured up and told so charmingly and with such restraint, where else is the real Thackeray so fully revealed, as when Esmond rides on from Walcote to the ‘George’ at Winchester on the fateful 29th December, and

walked straight to the Cathedral. The organ was playing, the winter’s day was already growing grey, as he passed under the street arch into the Cathedral yard and made his way into the ancient solemn edifice.

Wonderful is the chapter that follows—when Esmond and his ‘mistress,’ reconciled once more, first become mutually conscious of their love, and the words of the anthem, “He that goeth forth and weepeth shall doubtless come again with rejoicing, bringing his sheaves with him,” find their joyous refrain in the loving words they exchange.

But where is Walcote? Conjecture would almost naturally settle on Lainston House, some three miles away, the memories of which, in the person of the notorious Duchess of Kingston, doubtless suggested the character of Beatrix the incomparable, the breaker of hearts, the wilful and selfish beauty, did not distance put this out of question. Prior’s Barton House, at St. Cross, would fit us better. But the problem is a baffling one, if indeed it has any solution at all.

Of a different kind are the memories which linger round the immediate neighbourhood—the villages of Twyford, Otterbourne, Hursley. At Twyford the poet Pope was sent to school, and in a house close by the great Dr. Benjamin Franklin composed his autobiography; Otterbourne was the birthplace and lifelong home of Charlotte Yonge, the high-minded and accomplished, whose books will always be a standard for what is highest and most womanly in fiction—who loved to weave the details of local association with the stories she told so skilfully and well; and on a higher level still we have at Hursley the memories of Keble and the Christian Year,—not that Keble wrote the Christian Year at Hursley, though his connection with the place as curate commenced before it was completed, but his life-work was in reality here. Hursley Church, practically rebuilt by him from the profits of the sale of his Christian Year, is his truest memorial, and the beautiful church and peaceful churchyard, where he sleeps his last earthly sleep, will be ever a spot of hallowed association and pilgrimage. Winchester may be proud of its hymn-writers: Ken and Keble were two, and a third less well known, but certainly deserving to be honoured, was William Whiting, master of the College Choir School some two generations or so back, whose beautiful hymn, “Eternal Father, strong to save,” will ever hold a high place in the affections of church-going people.

Following on these memories we have a host of references in modern fiction which centre more or less definitely round the neighbourhood. Trollope’s Barchester has been conjecturally identified with Winchester, and there is a wonderfully minute and circumstantial correspondence in The Warden between the details of Hiram’s Hospital and St. Cross. Miss Braddon takes us to Winchester indeed, but gives us little, if any, actual picture of the city. The immortal Sherlock Holmes honoured it also with a visit in the Adventure of the Copper Beeches, keeping an appointment at the ‘Black Swan,’ “an inn of repute in the High Street,” and the Cathedral and Close seem to be suggested in the Silence of Dean Maitland. Allusions direct, and what seem allusions barely veiled, are frequent, but none can vie in tragic interest and solemn faithfulness with the last awful scene in Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles—when Angel Clare and Liza, her husband and sister, are awaiting the moment of poor Tess’s execution:—

When they had reached the top of the West Hill the clocks in the town struck eight. Each gave a start at the notes, and walking onwards yet a few steps they reached the first milestone ... and waited in paralysed suspense beside the stone.

The prospect from the summit was almost unlimited. In the valley beneath, the city they had just left, its more prominent buildings showing as in an isometric drawing—among them the broad Cathedral tower, with its Norman windows and immense length of aisle and nave; the spires of St. Thomas’s; the pinnacled tower of the College; and more to the right the tower and gables of the ancient hospice, where to this day the pilgrim may receive his dole of bread and ale....

Against these far stretches of country rose, in front of the other city edifices, a large red brick building with level grey roof, and rows of short barred windows speaking captivity, the whole contrasting greatly by its formalism with the quaint irregularities of the Gothic erections.... From the middle of the building an ugly flat-topped octagonal tower ascended against the east horizon, and viewed from this spot, on its shady side and against the light, seemed the one blot on the city’s beauty. Yet it was with this blot and not with the beauty that the two gazers were concerned. Upon the cornice of the tower a tall staff was fixed. Their eyes were riveted on it. A few minutes after the hour had struck, something moved slowly up the staff and extended itself upon the breeze. It was a black flag.[7]

Poor Tess! was it necessary for the author to mete out measure thus cruelly upon the children of his imagination—was it kind to Winchester to burden her memories with one so appallingly harrowing, so much in contrast with her quiet peace?

And yet, after all, is it anything more than retributive justice? Have not her citizens—those of a generation or so back, at least—been responsible for permitting the one really commanding elevation and landmark she possesses to be marred and dishonoured by this same ‘blot,’ these obtrusive prison-walls, capped by this self-same ‘ugly flat-topped octagonal tower’? Is not rather the creator of Tess displaying a fine and just critical perception in thus exacting from them the full literary penalty for so unpardonable an outrage on the outward attractiveness of their own fair city?

Such are some of the phantoms which pursue or elude us as we pass to and fro through the circle of Winchester and its surroundings—yet are they actual phantoms? Have not these seemingly impalpable nothings as complete an identity as the memories and records of the actual happenings of the past? The writer well recollects, after hunting through Salisbury and exploring its treasures of architecture and interest, the delight with which he came upon the old Cathedral organ, now for some years past removed from the Cathedral to one of the city churches, and recognized in it a real bond of relationship—not because it was originally the gift of George III., though that indeed was the case, but because it was the organ on which Dickens’s Tom Pinch had played when the Cathedral service was over, and his friend the organist’s assistant had permitted him to touch the keys. Not a great circumstance, nor a great character—far from it,—but sufficient to supply the one touch of human sympathy by which soul recognizes soul, and which binds all—past and present, student and subject, reader and author—alike in one. And even as these phantoms, whether of history or legend, of actual existence or fancy, have been conjured up before us for some brief spell, let us, now our task has drawn to a close, bid them adieu with what kindliness of recollection we may:

Come like shadows, so depart.