BUILDING A REFERENCE FILE

Because time and energy are important to a busy director, it is best to determine a method to develop a reference file. There are various ways that this can be done, including the obvious procedure of keeping the copies that you are interested in, and throwing away those that you do not care to use. This is actually not a method however, but the beginning of a method of cataloging information for future use.

It is first necessary to find music, and there are several ways to do this. One is to have your name placed on the mailing list of music publishers and dealers. Publishers are most happy to place copies of music in the hands of people who will want to buy their product. Of course, this means that you will receive many selections in which you will not be interested. Situations change, however, so it is best to examine all good music regardless of your immediate needs.

Attendance at workshops and clinics allows one to take advantage of reading sessions that offer music often selected by other directors. These sessions provide selected, rather than unsolicited, repertoire and many of them are most worthwhile. Also available at many of these sessions are repertoire lists. The disadvantage of lists is that you have no music to examine. However, you can take advantage of someone else's research and order reference copies of every work in which you are interested.

Conventions offer many of the above opportunities plus many concerts. These concerts, by carefully selected ensembles, will usually contain interesting and stimulating repertoire. Conductors are aware of the makeup of professional convention audiences and want to put their best possible repertoire on display. Again, it is best to order a copy of each piece with which one is unfamiliar.

In addition to the above sources, several professional organizations offer lists of recommended repertoire. Several publications are available from the Music Educators National Conference, the American Choral Directors Association, and the American Choral Foundation. Informatioin on these organizations can be found online.

If you follow the suggestions made above, you will receive hundreds of copies of music a year. It would be foolish to keep every copy of music. The sheer bulk of it becomes a burden and you will not be interested in studying or performing all of it. Filing the copies in a cabinet does nothing to aid you in future searches for literature. Six months (or years) later you will have to sort through each file, copy by copy, to find music that you wish to perform. This duplication of effort is too costly in terms of time and energy, and is a contributing factor toward poor planning on the part of some directors.

The procedure that follows is one based on some years of use and was found to be practical, thorough, and useful for future reference.

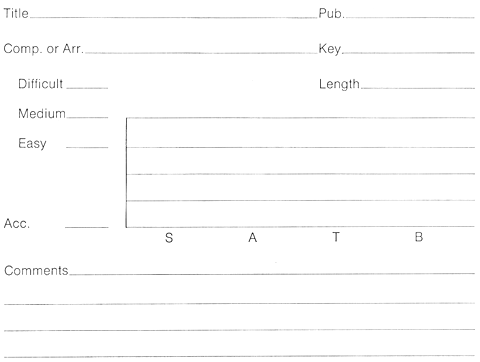

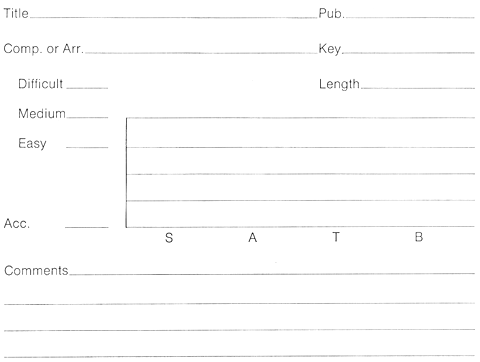

It is much easier to have the information you desire in a card file or in a computer program than to look at all of the reference copies. The card, or its computer counterpart contains all of the information you desire for the moment, is portable, and can be taken from home to the office, etc., and will actually stimulate you to better examination of the music the first time. Later, for example, when you want to develop a group of four Renaissance motets for a Lenten season concert, you can do a quick card search, pull the cards on these pieces, know the approximate length of the work, the voicing, and the difficulty level as you have determined it. You may choose eight or ten possibilities and then examine the actual music for these pieces and choose the four that you wish to perform. The card may look like the one printed in the figure below or vary from it to suit your personal desires.

Complete a card only on the pieces that you consider worthy of future use. In addition to general choral works, these may include seasonal pieces, specific occasion works, and several pieces placed in a special category—perform as soon as possible.

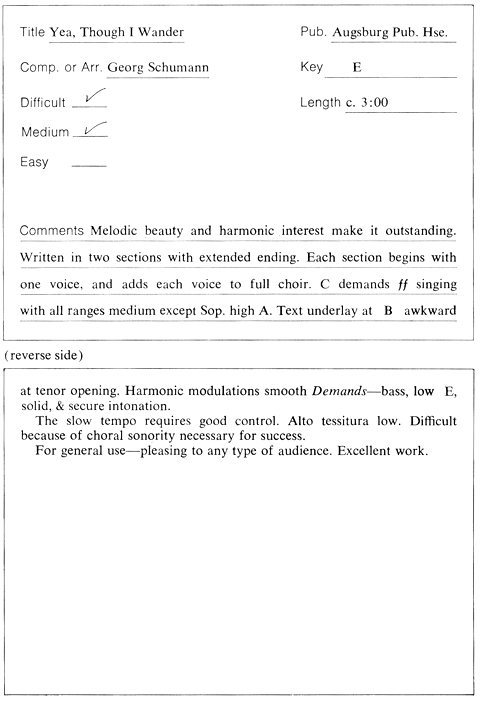

The figure below is a sample of the manner in which a card may be completed on a specific choral work.

Your comments need to be specific enough to remind you of the qualities of that particular work. It is also best if you record your impressions of the piece ("very well written," "one of the best settings of this text I have seen," "the advanced choir will like this one") and your indications of specific performance use ("would work well at the end of a group," or "good opener"). Remember that the comments you write must be those that will best recall the work to your mind when you review the card.

The cards can be filed in alphabetical order by title or by composer. Filing by composer has the advantage of a more chronological ordering without actually formalizing it as such. You will recognize Victoria as Renaissance, for instance, but O ,MAGNUM MYSTERIUM has been set by many composers. Filing by musical period is usually not as good because the lines separating the periods are not as clear.

The remainder of this chapter consists of criteria on which the judgments of selection of repertoire can be based. Once a director becomes accustomed to applying these criteria to each new piece he views, the process will become automatic and time-saving. In addition, it will enable him to choose music that is most appropriate for his ensembles.