The pitch retention test is one of the best determinants of the student's possibilities for success in a choral ensemble. It will tell you, quite accurately, of the student's potential to learn to read music and to learn choral repertoire. This method of auditioning is used by a number of leading high school, college, and university choral directors.

To require sight-reading at choral auditions may be of value when auditioning very experienced and well-trained singers, but a sight-reading test in a choral audition of younger, rather inexperienced singers is of little value. It generally reveals what a nervous person, faced with a new piece of music with unfamiliar words, cannot do while under the watchful eye (and ear) of the choral director. It does not indicate the potential of the person to read music or to learn choral repertoire in a choral rehearsal situation. This author's experience, and the experience of others, has shown conclusively that a pitch retention (PR) test is a reliable guide for the selection of choir members. It has been found that, when good voices with low scores on the PR were admitted to a very select ensemble with high performance demands, it was usually regretted later. On the other hand, when a student with little background but with a high score on the PR was admitted, even in place of a more experienced person whose PR score was lower, that decision was never regretted. The PR also indicates to the choral director persons who will have difficulty singing in tune. Since intonation is such a crucial factor in a choral ensemble, this information is very useful at the time selection is made. A director may have to use a PR test for some time before he will place full confidence in it, but eventually he will be able to rely on it as an accurate guide to a student's potential as a choral singer. After using a pitch retention test the choral director will most likely wish to eliminate sight-reading from most auditions completely.

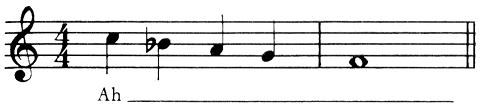

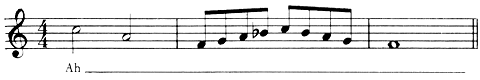

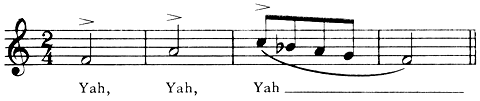

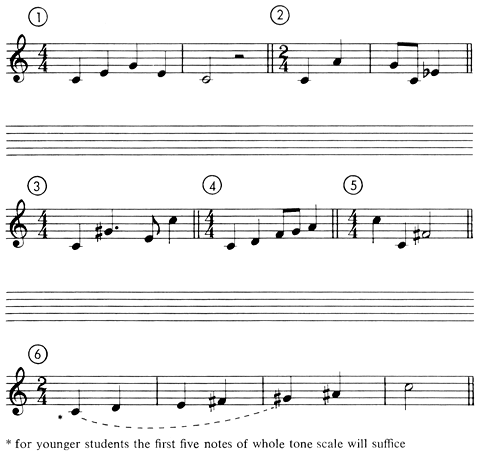

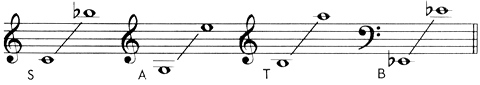

The pitch retention test given in figure 1 has proved successful at the high school, college, university, and community levels.

When administering the test be certain that:

1. The room is free of other noises and distractions.

2. Waiting students cannot hear the test.

3. Each exercise is played only once, asking the student not to hum the notes as they are being played. If the student asks to have the exercise repeated, subtract a proportionate amount from his score.

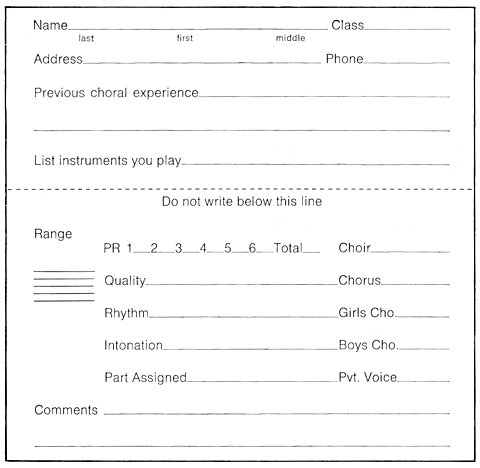

4. The results are scored so a glance at the card later will provide you with all the information you desire. The sample card allows for six exercises and a total score. Each director will find it easy to determine his own method of scoring.

5. Each exercise is played accurately, with all notes played at the same volume level.

6. The piano has recently been tuned.

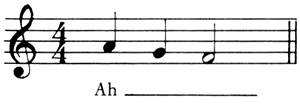

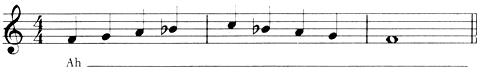

This author recommends that directors who wish to have students sight- read in addition to the pitch retention test write several short exercises for this part of the audition. More reading problems can be incorporated in this manner and less time wasted than when a choral score is used.