STARTING ON THE LAST BEAT

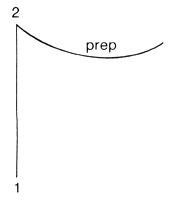

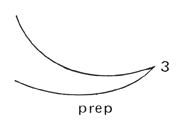

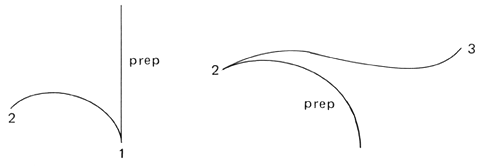

If the last beat of the measure is the first beat on which sound begins, the previous beat of the pattern will be used as a preparation. For example, if the first sound occurs on the fourth beat of a 4/4 measure, the third beat of the pattern would be the preparatory beat (see figure 1).

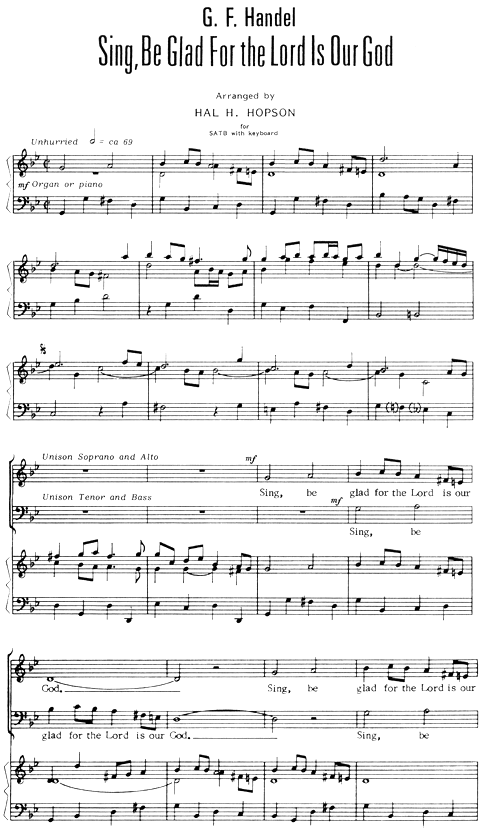

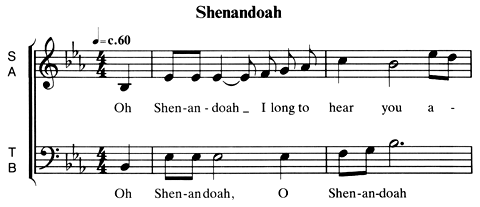

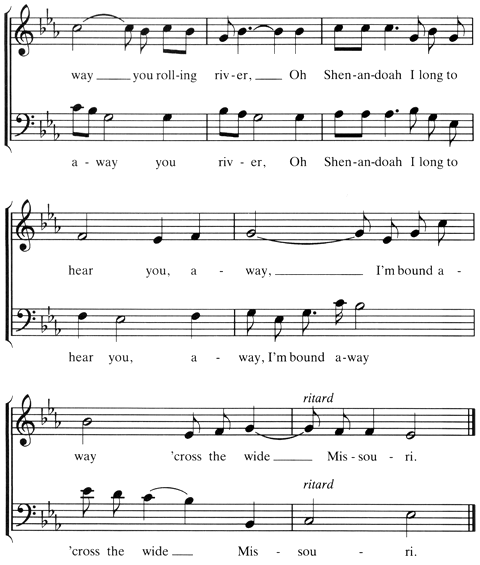

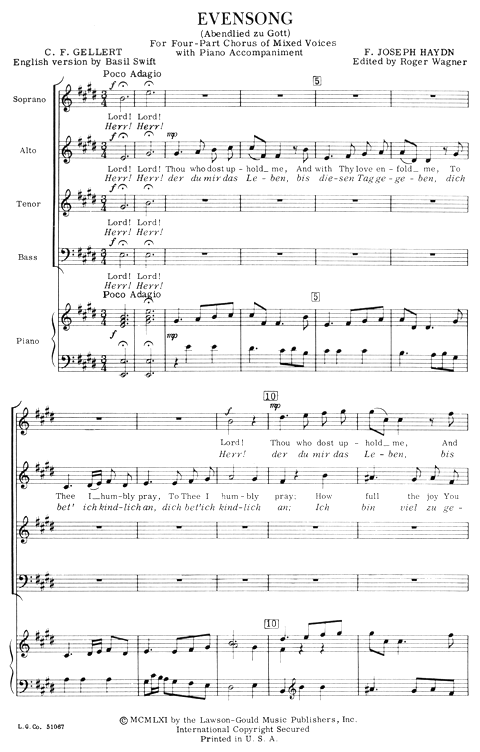

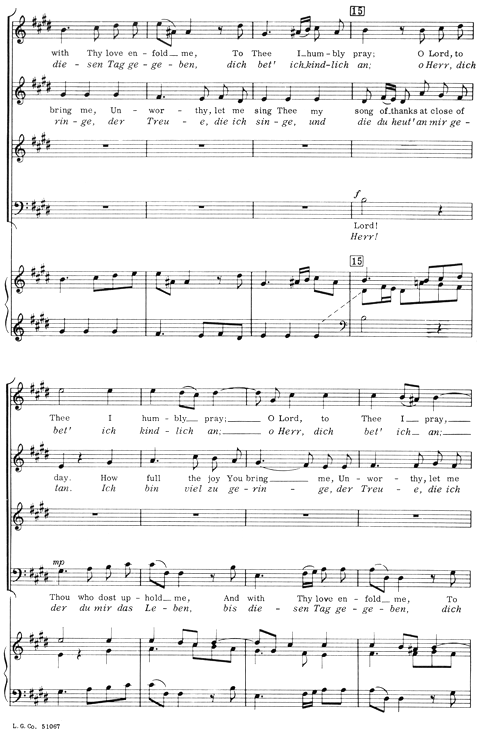

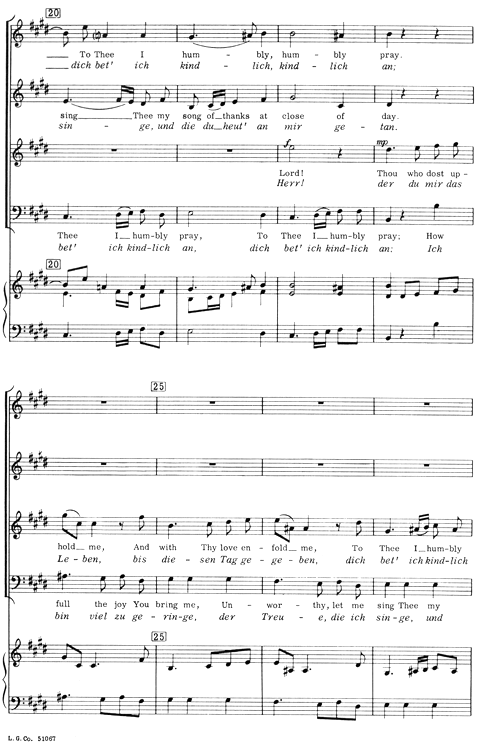

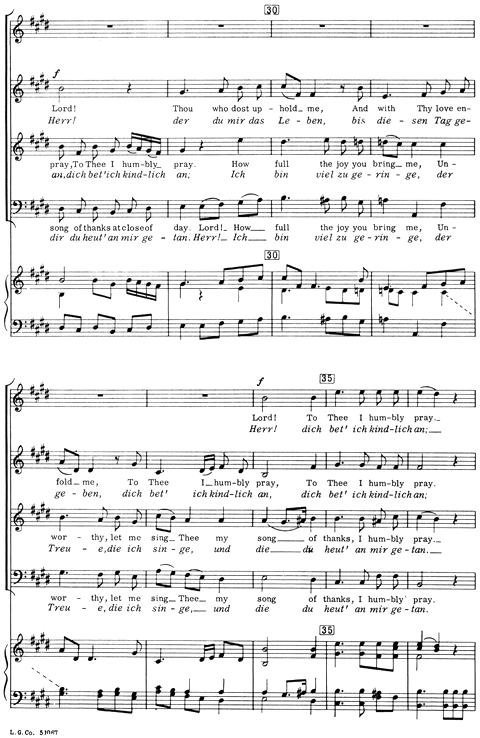

The following example Shenandoah begins on the last beat of the measure, requiring the third beat as a preparatory beat. The slow tempo and legato style are excellent for practicing this technique. The several conducting problems in this one verse arrangement and the setting for only two voices also make this a useful conducting tool.

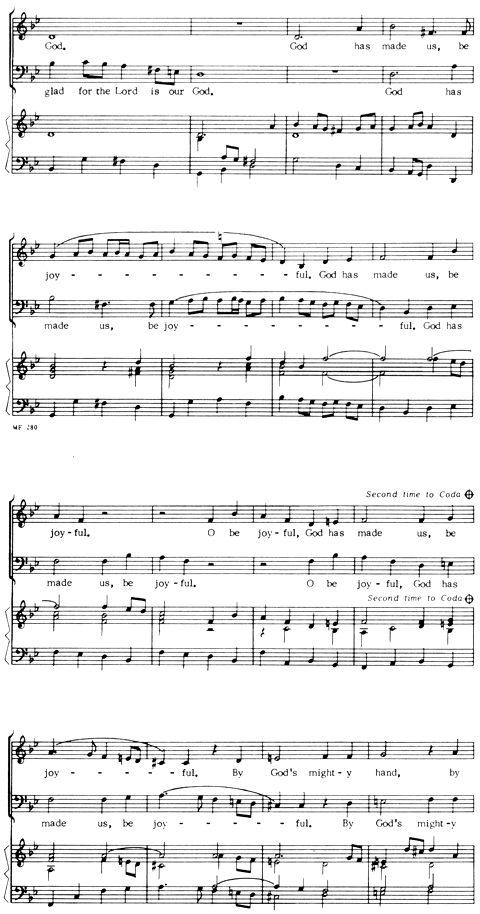

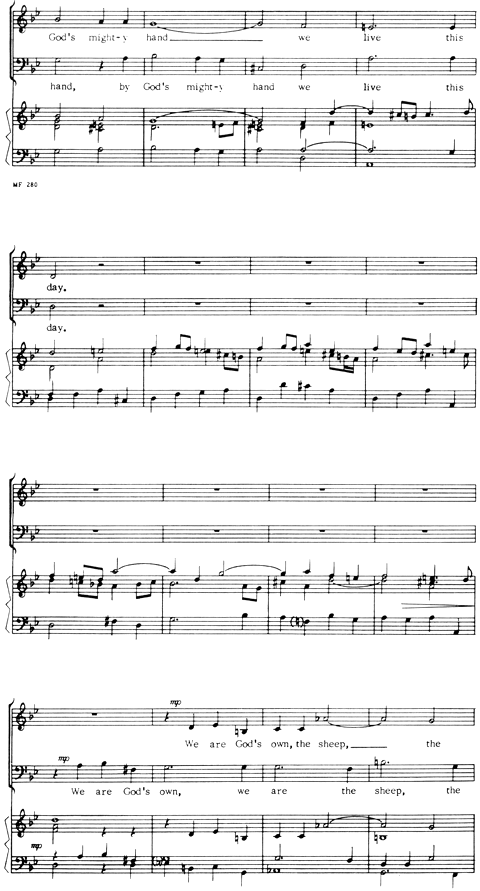

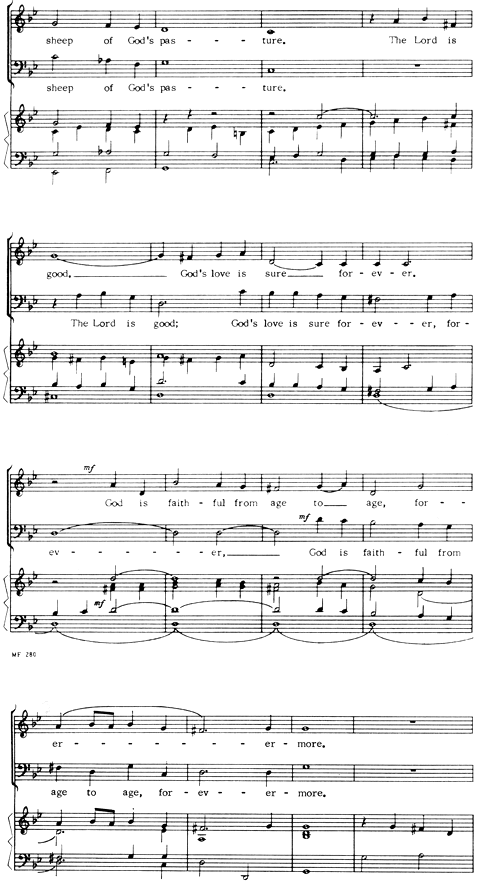

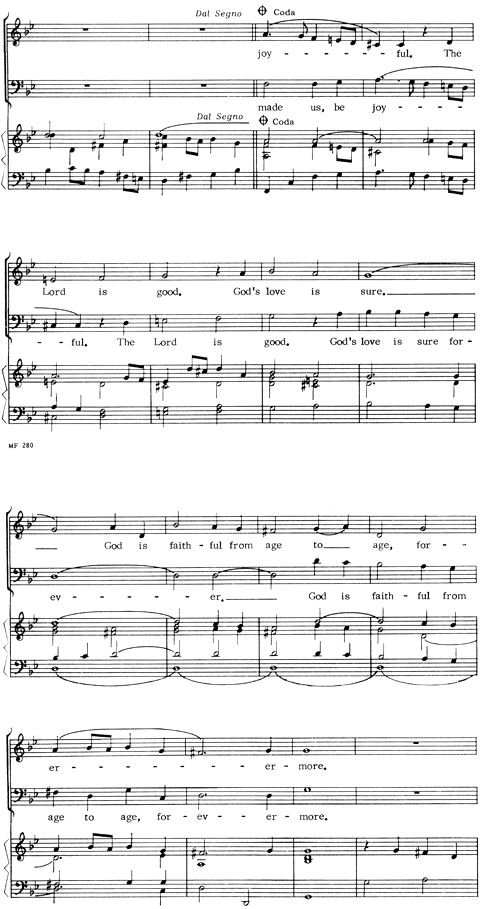

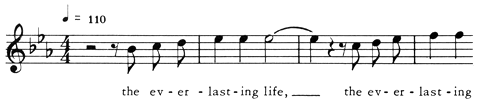

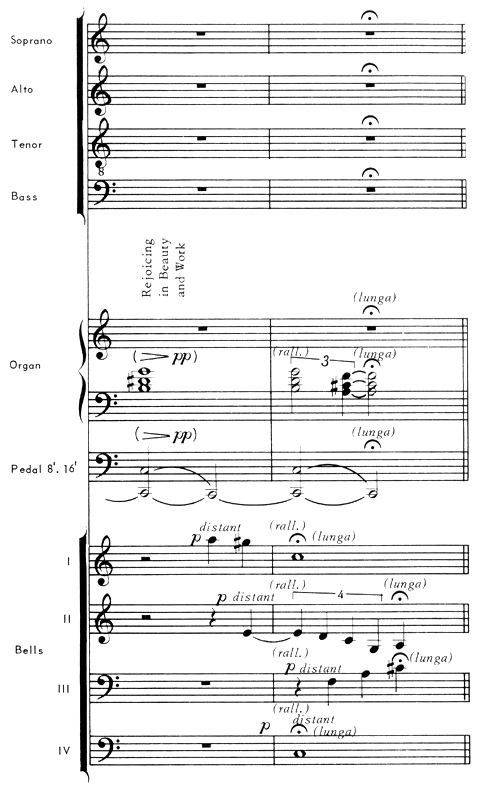

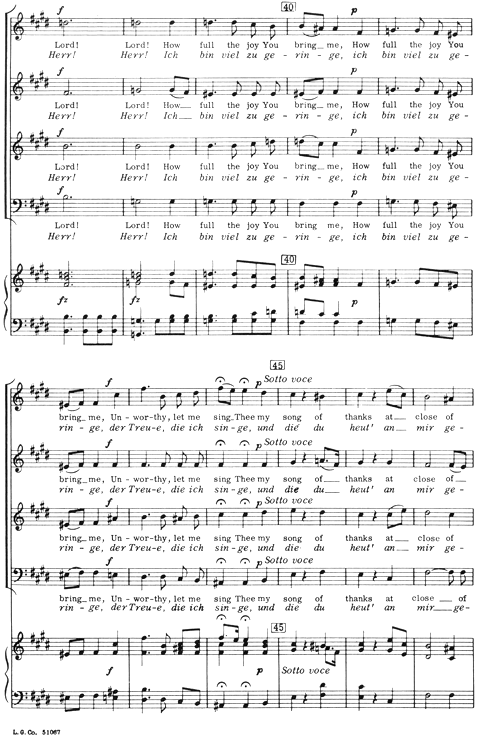

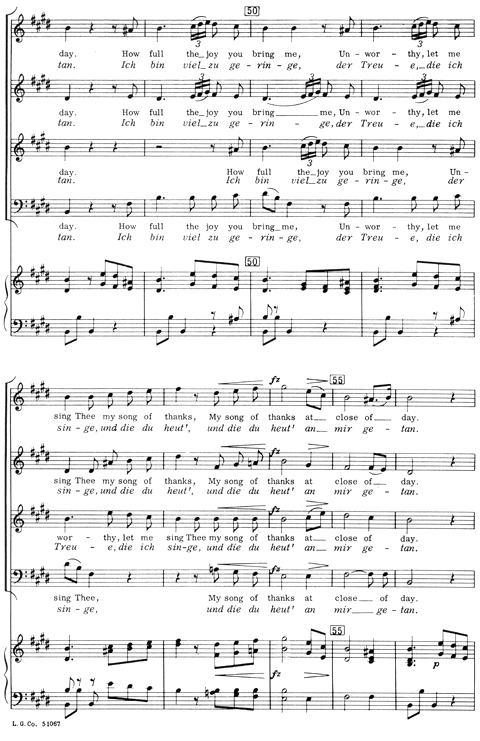

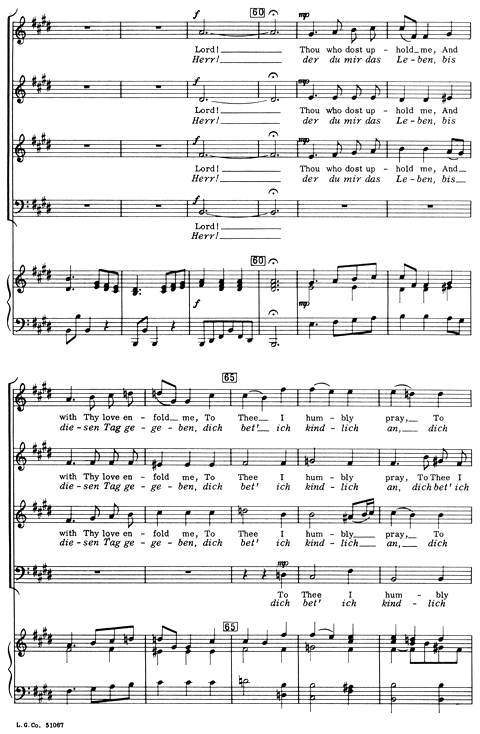

The well known In Dulce Jublio by Michael Praetorius begins on the last beat of a measure. After the brass verse the voices begin on the first beat of the measure and, because of the finality created by the fermata on the brass chord, this is very much the same as beginning a piece on the first beat. So, both techniques can be practiced in this piece. Incidentally, (and not so incidentally when you are looking for good music that is not difficult), neither the brass nor choral parts are difficult and the ranges of both are excellent.

The transition from 3/4 to 1 can be tricky for both the choir and the conductor. The choir relies on the conductor to define and clarify the half note as having two quarter notes within it instead of three. Where there were three distinct gestures in a measure there are now only two, and each of those encompasses the duration of all three of the previous gestures.

Two aids to assist in this transition are: (1) the choir can mentally begin thinking in two as it arrives at the last bar of the 3/4, the dotted half note. Since the half note of the following two pulse equals the previous dotted half note in length, the final dotted half note represents one beat of the new two pulse and (2) the conductor can use only one gesture in that final 3/4 measure, a gesture that equals the half note pulse (and gesture) of the new two pulse measures. Granted, the brass have eighth notes and quarter notes still clearly in 3/4 but, since that pulse has been so clearly established from the beginning, they should have no difficulty in playing accurately within that gesture.

On the other hand, one can conduct in three until the change, and change the gesture at that point to a clear two beat gesture and have equal success. Whatever you decide to do, and you could experiment with both, as you get close to performance select one technique and stay with it, so both the brass and choir understand and can anticipate your gestures.

Because of the alternation of brass and choir this is an excellent practice piece for conductors. The problems of leaving one group to attend to another are several and will become apparent. Because of this alternation, this piece is quite effective in performance. One of the reasons is because the brass rarely play as the choir sings. Consequently, the choir is not overpowered by the brass instruments. Another nice feature is that the brass parts sound very nice at Mf, Mp, and P volume levels, particularly when played with a light tonguing technique. There are several editions available.