Two scores have been chosen as examples of the application of score study. The first, a twentieth-century score Praise Ye The Lord by Paul Fetler, is examined in some detail following the procedures described above. The second, Now Thank We All Our God by Johann Pachelbel is presented in an overview. The overview is necessary for conductors to be certain they do not become so engrossed in the details of the score that they lose sight of the large dimensions of the work. The chapter ends with a discussion of indeterminate scores and the specific problems they present.

Praise Ye the Lord, Paul Fetler

Published by G. Schirmer, Inc.

The short choral phrases in this concert anthem are inserted into the unrelenting fabric created by the staccato piano part. The overall dynamic scheme of pp—fff—pp presents the choir with the full gamut of dynamic possibilities in this distinctive setting.

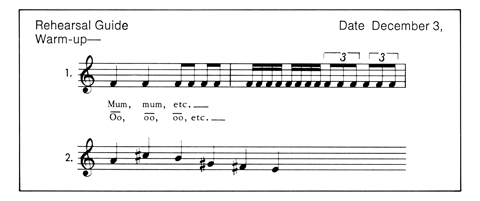

Figure 1 shows the opening piano accompaniment and the first choral statement. Both are representative of much of the writing throughout the work.

Melodically, the work is comprised of a number of short phrases quite similar to those in figure 1. Intervals of particular importance are the ascending minor third (as seen in the alto and bass of measures 7 and 8) and the perfect fifth (which occurs later in the composition).

The harmony is conservative twentieth-century writing using many chords of open fourths and fifths. Harmonic interest is achieved through frequent major second dissonances that occur as a result of paired fourths and fifths and as melodic occurrences as seen in figure 2, measure 7.

The single most important element of the piece is the rhythmic activity. Syncopation creates interest and excitement as it occurs in the choral parts over the constant eighth note in the piano. This rhythmic activity at the fast tempo is one of the outstanding qualities of the work.

PRAISE YE THE LORD, By Paul Fetler, Copyrigtht 1972 (Renewed) by G. Shirmer, Inc. (ASCAP), Internation Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved, Reprinted by Permission

Fetler uses brief moments of legato writing as contrast, as seen in figure 4. Except for the one instance of two-part writing, these legato passages occur as unison statements. Figure 5 shows a return to the declarative statements.

One of the first rehearsal, and later performance problems, encountered is the fast tempo. Of course, first rehearsals need not be at tempo, but it later becomes an element of concern. Although the accompaniment is not technically difficult, it is hard for a pianist to maintain the desired tempo, and to do so at the various dynamic levels required in the score. Conductors must also resist the urge to allow the music to become slower. Performances often start at tempo but a slowing occurs (usually within the first thirty measures) that dulls the urgency and excitement the composition should have.

Other than the usual problems of correct notes, intonation, tone, etc., the two major problems caused by the rhythmic activity and the fast tempo are lack of clarity and poor diction.

Because of the speed, clarity becomes a particular problem of this piece. The articulation of the notes must be clean. The choir will have to adopt some of the staccato quality of the piano accompaniment in order to sing these passages cleanly.

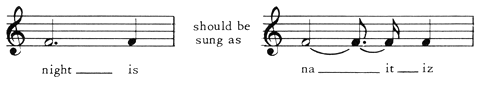

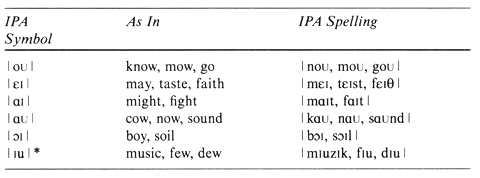

Good diction not only allows the audience to understand the text but also contributes substantially to solving the problem of clarity mentioned above. One of the problems of this piece is the fast articulation of "Praise ye." Choirs will often sing "Prashee" instead of the correct "Praz ye." The s in Praise is sounded as a z. Conductors will find it necessary to emphasize to the choir that the z must be carefully sounded and that it should not be too long.

Although Praise Ye the Lord is not a difficult work, conductors will find that it must be well paced; that the choir must be cautioned not to reach a forte too quickly. Close attention to the careful dynamic markings of the composer will aid the conductor's pacing of the piece. The urgent intensity of the very soft passages explodes in the fortissimo center section of the work. The return to pianissimo is not easy to achieve but provides a satisfying ending to the composition.

Now Thank We All Our God (Overview), Johann Pachelbel, (edited by Eggbrechet)

Published by Concordia Press

No 98-1944

This setting of a chorale tune is only one section of a larger work. The chorale is in the soprano, preceded by alto, tenor, and bass parts derived from the tune. This is often referred to as one type of cantus firmus treatment before Bach. A tempo of a quarter note equaling eighty (eighty quarter notes in a minute) is suggested. The alto, tenor, and bass are important until the entry of the chorale tune, at which time they must become subordinate to the melody. One must keep the three lower parts from becoming too heavy. A light, free texture is necessary.

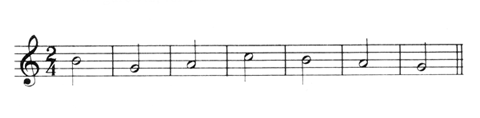

The rhythmic life of the lower parts, coupled with a clearly defined cantus firmus, is the key to success in this piece. Attention must be given to the eighth note; each must be a full eighth note. A slight broadening of the second and third eighth notes in the groups of three will help obtain the rhythmic security so necessary to this work.