There are so many details to the study of English diction that one chapter cannot possibly cover the subject. It deserves an entire book by itself and several are suggested at the end of this chapter. The purpose of this chapter shall be to call attention to the principles of good diction and make suggestions that can improve choral diction.

It should be mentioned at the outset that the union of text and music often results in an artistic environment in which music has the distinct advantage. Authors of prose or poetry are usually not enthusiastic about the results of their words being set to music because the music occupies the foreground and the text the background. Words, when sung, can sometimes be difficult to understand. When words are lengthened by extension of vowel sounds, necessary for singing but unnecessary and probably undesirable in text declamation, considerable audience concentration is required to link the fragments of words and phrases together. The length of time occupied by one vowel sound may be so long that the sense of the entire word is lost before the vowel's place in the text stream is defined by the next sound, either a consonant or a new vowel sound. When the text is unfamiliar to the audience it is very helpful to print the text in the program or in an insert. Every text should be carefully enunciated, but to expect even a carefully enunciated text to be always understood is simply not realistic for every occasion. Choral polyphony of any period is only one example when a text will be difficult to understand. Familiarity with the text allows the listener to appreciate the manner in which the composer has set the words. There is certainly merit in allowing the listener an opportunity to become familiar with a new text at a concert before hearing the setting.

Choirs are almost always involved in communicating a text to an audience. Intelligibility of text will come through consonants that are short and clean, and through correctly formed vowels that are uniformly pronounced throughout the choir. Although there are some exercises aimed directly at diction it is rarely necessary to work in that manner. A choir director is always working on diction no matter what other purpose may also be in his mind. For instance, when a director is working on tone, he is dealing with vowels. His choir will not develop a satisfying tone or sing in tune until they are singing the same vowel sound. So, no matter what the concern, diction is always part of it. The key to good tone, good intonation, and good blend lies in a single, unified vowel sound. In the course of this chapter, several techniques will be suggested that will help a choral director achieve the best possible diction with his choir.

Singing diction should be nonregional; it should not reveal the native state of the performers. It may take a major effort on the part of the choir director to convince the singers that the sounds they make in everyday speech will be undesirable when elongated in a choral work. To "sing as we speak" would only be a correct instruction if we all spoke the same way and if we all spoke the English language correctly. The facts are that we all do not speak the language the same way (note the differences in pronunciation between the southern area, the southwestern area, the midwestern area, the northern midwest and the northeastern area). There are still further subtle differences within each of these areas. The director must also impress upon the singers the difference between sustaining a sound on pitch and quickly passing over it in normal conversation.

Figure 1 lists the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) for single vowel sounds, diphthongs, triphthongs, and consonants. For the purposes of our discussion, single vowel sounds are those that have only one vowel sound for the duration of the word or syllable. Diphthongs are defined here as two consecutive vowel sounds, and triphthongs as three consecutive vowel sounds. Learn to use the IPA symbols and be able to apply them to choral texts. This is the best possible way to ensure consistent and correct pronunciation. Anything less than a concerted and disciplined approach will result in erratic diction.

Before any of these vowels can be correctly pronounced, they must be correctly identified. This is a problem for many directors since it is apparent that some choirs make a directed and unified effort toward a wrong pronunciation of some words. One example of this is the word sing ǀ ʂɪŋ ǀ. It is often heard pronounced as ǀ siŋ ǀ, which is incorrect. There are many choral directors who ask their students to modify ǀ sɪŋ ǀ toward ǀ siŋ ǀ, and even ask them to use an ǀ i ǀ sound on occasion. The knowledgeable director may ask his choir to sing with a brighter ǀ ɪ ǀ sound but does not actually want the sound of ǀ i ǀ. It is the director who misapplies or overdoes the technique of brightening the vowel whose choir sounds strange on the concert stage. Good diction should not sound strange. When good concert diction is achieved, an audience should recognize it as refined English. Certainly no one would expect gutteral or dialectal speech on the stage. 2

Figure 4 applies the IPA symbols to the single vowel sounds and lists several examples of these vowels in use. Practice speaking the sound of the words and writing them with the proper IPA symbol. This will help establish a consistent approach to diction that will have a lasting and positive effect on the sound of the choir.

Two possible symbols have been purposely omitted, ǀ ɒ ǀ, a short o sound and ǀ a ǀ an intermediate sound between ǀ æ ǀ and ǀ ɑ ǀ. The first ǀ ɒ ǀ is generally not used in the United States. The words to which it is applied, hot, top, etc., are usually pronounced as ǀ hat ǀ, ǀ tap ǀ. This pronunciation is more practical and consistent with our usage. The latter ǀ a ǀ is also not practical since we do not usually make the sound between ǀ æ ǀ and ǀ ɑ ǀ. All of the words to which this symbol is applied may be pronounced either ǀ æ ǀ and ǀ ɑ ǀ.

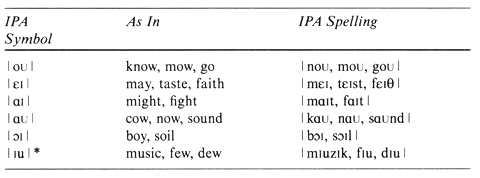

Figure 5 lists diphthongs with their IPA symbols. In all cases but one, the first vowel sound is the one that should receive the emphasis.

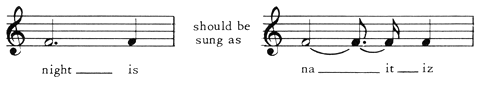

In order for the word to be correctly pronounced and ultimately understood, the first part of the diphthong must be held as long as possible during the duration of the note. The second vowel sound should be placed at the very end of the note. The transition to the second sound should be a smooth glide and should never be abrupt.

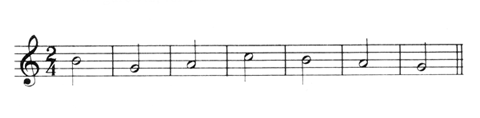

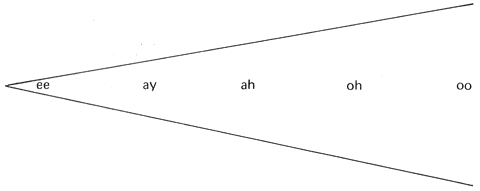

This principle, as illustrated in figure 3, may be applied to other words. This is only a metrical illustration and does not intend that the second part of the diphthong should take on rhythmic significance. It is important that the vowel be formed deep in the mouth, and that this deep vowel be maintained until the very last moment.

The exception to this is the | ɪʊ | diphthong, which is marked with an asterisk in Figure 5. In this instance the first vowel sound is quickly sounded and the second vowel sound is elongated.

1. In some instances of avant-garde literature the composer does not attempt to communicate a text. There are also pieces of traditional music in which the choir may communicate the sense of the text rather than a literal transmission of it.

2. There are some obvious moments when choirs should use a dialect—spirituals, some folksongs, etc.