Some choral directors use vocal warm-ups at the beginning of a rehearsal because they believe the warm-ups will make the student's voice ready for intensive rehearsal. Some of these directors use the same warm-up exercises in every rehearsal and strive to obtain maximum results with their use.

Other choral directors use warm-up exercises only because they think they are supposed to use them. They do not have a planned use for them but use them because they do not know what else to do to start the rehearsal.

The use of vocal exercises only to free the singer's voices and ready them for rehearsal is an inefficient use of rehearsal time. While it is true that these two factors are important, it is equally as true that much more can be gained through the use of this time. Try to incorporate some rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic elements from the music that is being rehearsed into some of the opening exercises. This does not mean that this must be done with each exercise or all of the time, but that one exercise can be slanted to a particular rehearsal problem. This can be done with just a little planning and the use of a chalkboard.

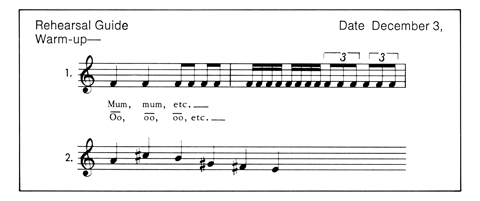

One example of this is a passage that this author used as an exercise to develop cleanly articulated runs for several weeks before the music from which it was taken was even distributed. It was apparent that it (and one other similar passage) would cause rehearsal problems because both were to be sung at a moderately fast tempo, and by the basses, often the least flexible section of the choir.

The passage given in figure 1 was placed on the chalkboard twice and sung by all voices on several vowels and syllables. It was even sung once or twice on the text "dispersit." This was done at various moments in several rehearsals to change from one style to another style of repertoire or as a beginning exercise. After the second time it was not necessary to write it for the students. When it was finally introduced later as part of a work, it had already been learned and needed no further attention. When this is done, no mention will need to be made of its existence in any piece. The students will be aware of it when it occurs in a selection, or it can be mentioned when the piece is introduced.

This use of actual music in exercises can be done with many pieces of music and in a variety of ways. It can save valuable rehearsal time and make learning easier and more enjoyable for both the choir and the director. The example shown above is a bit extreme in range and one may desire a less extreme exercise.

Several general exercises are listed below that can be used to open a rehearsal or can also be used any time during the rehearsal. Each of them is discussed briefly. Although the exercises are notated in one key, they can be transposed to any key and moved by half or whole steps through various parts of the student's range.

A few general comments about the use of exercises is needed first. It is best not to use the same exercises every day. No matter what they are, they can become boring. Mix the exercises, but mix them so, over a period of one to two months, the ones that are basic to the development of a good tone occur in a steady cycle. Do not hesitate to use exercises at points in the rehearsal other than the beginning. After some strenuous singing, exercises can let the singer relax the throat and, once again, unify the choral tone.

Which exercise to use depends on the point the ensemble has reached in its choral development. Some directors remark publicly that, ". . . no matter what choir I conduct, I always use these two exercises, . . . ." Any conductor who makes this statement is ignoring the capabilities and differences of singers. It makes no more sense than saying, ". . .no matter what choir I conduct, I always use the same piece of music." There are some choirs at the college level that can achieve a desirable choral tone through choral repertoire without the aid of exercises per se. This is probably not true of high school or most church choirs, however.

There is also no reason that some rehearsals cannot begin without exercises. If the director chooses carefully, the students can free the throat and warm up the voice using a piece of music instead of a vocalize. One does not have to use the text of a piece all the time, but can have the choir sing the parts on any given vowel. In this manner the director can rehearse the notes and rhythm of a piece and still get the voices warmed up.

Another important aspect of the opening part of the rehearsal is that of tuning up. The warm-up is a tune-up also. Sometimes the students do not need to have the voices warmed-up but they do need to tune-up, refining the use of their voices within a choral ensemble toward a unified goal. This aspect should not be ignored because it is the part that helps to reorient students to the rehearsal. The moment a student begins to refine the use of his voice, to listen to the vowel color, to listen to the voices of others, and to contribute to a choral tone that has beauty and warmth, he will have turned his mind on to the choral rehearsal.

Work for a choral tone that has ringing resonance and a deep, rich warmth. This is much easier to say than to do. It is the tone that most choral conductors are aiming for. This tone will not happen accidentally, although one will occasionally have students who, without any prior training, sing with a tone that is very close to that desired. Usually these students cannot maintain the tone consistently throughout their range; good voice training will help gain that control.

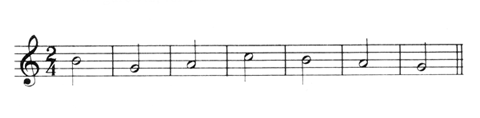

Choirs need both the forward resonance and the depth. Several exercises can be used to help acquire both. Figure 2, the first figure, is an exercise that can be used to develop a focused tone with a forward placement. Have the singers accent the h and go immediately to the hum. Each singer should make the abdominal muscles tense at the attack. Cue the singers to move slowly from the m to the ee. Tell them to try to maintain the ring or buzz of the m in the ee. This is a good exercise for the first part of the year when extra attention will also be given to breathing, and at any time to overcome breathiness.

Another similar exercise that serves much the same purpose as the above is shown in figure 2, the second figure.

Let the first note be held on the "ning" sound. Change smoothly to the ee and hold as long as desired. The first note should not be accented but should be started with a clear attack. After you are convinced that you are getting the best possible sound on the ee, let the students sing from hm or ning to ee and then to eh. The next step is to add an ah vowel to both of the above—from ee, to eh, to ah. This is the most difficult transition to make. Most often the forward ping in the tone is lost when the ah is begun. The tone seems to fall down in the mouth as the ah is reached. Some imagery will be valuable here. Try to suggest the image that the vowel "stands up" in the mouth, that it is then alert and has forward resonance. The tone needs to follow a path up the back of the mouth, over (following the roof of the mouth), and out, just below the upper teeth. This ca