The Sections of the Orchestra

The typical orchestra is divided into four groups of instruments: strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. The typical Western marching band, school band, or wind ensemble (woodwinds and brass together are winds) leaves out the strings, but otherwise uses most of the same instruments as the orchestra.

There are four stringed instruments commonly used in the modern orchestra: the violin, viola, cello, and bass. All are made of wood and have four strings. All are usually played by drawing a bow across the strings, but are also sometimes played by plucking the strings.

The violin is smallest, has the highest sound, and is most numerous; there are normally two violin sections (the first violins and second violins), but only one section of each of the other strings.

The viola is only a little bit bigger than a violin, with a slightly deeper and mellower tone. A nonmusician can have trouble telling a viola from a violin without a side-by-side comparison.

The cello is technically the "violoncello", but few people call it that anymore. There is no mistaking it for a violin or viola; it is much bigger, with a much lower, deeper sound. Whereas violins and violas are held up under the chin to be played, cellos and basses have to rest on the floor to be played.

The bass, also called the "double bass" (its official name), "standing bass" or "string bass", is so big that the player must sit on a high stool or stand up to play it. It has a very low sound.

The woodwind members of the orchestra are the flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon. There can be two, three, or four, of any of these woodwinds in an orchestra, depending on the size of the orchestra and the piece being played. All of the modern orchestral woodwinds are played by blowing into them and fingering different notes using keys that cover various holes. Most, but not all, are made of wood and have at least one piece of reed in the mouthpiece.

You may be surprised that the saxophone is not here. This is the one instrument that is always found in bands and wind ensembles, but only very rarely plays in the orchestra.

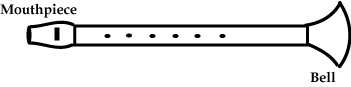

Although flutes may be made of wood, the orchestral flute is usually made of metal. It also does not have a reed. It is grouped with the woodwinds partly because it is in fact more closely related to those instruments than to the brass (please see Wind Instruments: Some Basics), but also because the color of its sound fits in the woodwind section. The sound is produced when the player blows across a hole in the side (not the end) of the instrument. It has a clear, high sound that can be either gentle or piercing. An even higher-sounding instrument is the piccolo, a very small flute that is much more common in bands than in orchestras.

The oboe is the instrument that traditionally sounds the first "A" that the orchestra tunes to. It is black, made of wood, and at sight can be mistaken by the nonmusician for a clarinet. But its sound is produced when the player blows in between two small reeds, and its high "double-reed" sound is not easily mistaken for any other instrument. The cor anglais, or English horn, is a slightly larger double reed instrument with a deeper, gentler tone, that is sometimes called for in orchestral music.

The clarinet is also black and normally made of wood, although good plastic clarinets are also made. It uses only a single reed. It is a versatile instrument, with a very wide range of notes from low to high, and also a wide range of different sound colors available to it. In the orchestra, clarinets are no more numerous than the other woodwinds, but it is usually the most numerous instrument in bands and wind ensembles because of its useful versatility. There are many sizes of clarinet available, including bass and contrabass clarinets, but the most common is the B flat clarinet. The clarinet is the only common orchestral woodwind that is usually a transposing instrument, although there are less common woodwinds, such as English horn, that are also transposing instruments.

The bassoon is the largest and lowest-sounding standard orchestral woodwind. (Bass clarinet and contrabassoon are used only occasionally.) It is a long hollow tube of wood; you can often see the tops of the bassoons over the rest of the orchestra. Like the oboe, the bassoon is a double reed - the player blows between two reeds - but the player does not blow into the end of the bassoon. The air from the reeds goes through a thin metal tube into the middle of the instrument.

The orchestral brass are all made of metal, although the metal can be a silvery alloy instead of brass. The sound is actually produced by "buzzing" the lips against the mouthpiece; the rest of the instrument just amplifies and refines the sound from the lips so that it is a pretty, musical sound by the time it comes out of the bell at the other end of the instrument. A slide, or three or four valves, help the instruments get different notes, but players rely heavily on the harmonic series of their instruments to get the full range of notes. (Please see Wind Instruments: Some Basics for more on the subject.) The orchestral brass instruments are the trumpet, French horn, trombone, and tuba. As with the woodwinds, the number of each of these instruments varies depending on the size of the orchestra and the piece being played. There are usually two to five each of trumpets, horns, and trombones, and one or two tubas.

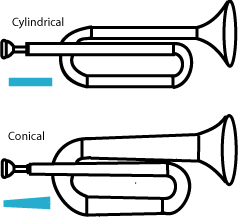

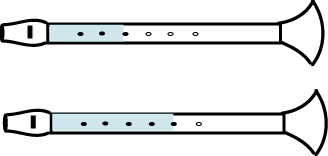

The trumpet is the smallest, highest-sounding orchestral brass instrument. Its shape is quite cylindrical (it doesn't flare much until the very end), giving it a very clear, direct sound. Trumpets may read in C or may be B flat transposing instruments. The cornet, which is more common in bands than in orchestras, is very similar to the trumpet and the two instruments are often considered interchangeable. The cornet has a more conical, gently-flaring shape and a slightly mellower sound.

The French horn, or horn, is much more conical than the trumpet and has a much mellower, more distant sound. It has a wide range that overlaps both the trumpet and trombone ranges, and in the orchestra is often used to fill in the middle of the brass sound. Its long length of tubing is wrapped into a circular shape and the bell faces backward and is normally rested on the player's leg. It is a transposing instrument that usually reads music in F.

The trombone is the only valveless brass instrument in the modern orchestra. One section of its tubing - the slide - slides in and out to specific positions to get higher and lower pitches, but, as with the other brass, it uses the harmonic series to get all the notes in its range. Its range is quite a bit lower than the trumpet, but it also has a brassy, direct (cylindrical-shape) sound.

There are a few instruments in the middle and low range of the brass section that are commonly found in bands, but very rare in the orchestra. The baritone and euphonium play in the same range as the trombone, but have the more cylindrical shape and a very mellow, sweet sound. In marching bands, the horn players often play mellophone and the tuba players play the sousaphone. The mellophone is an E flat or F transposing instrument with a forward-facing bell that is more suitable for marching bands than the French horn. The sousaphone was also invented for use in a marching band; its tubing is wrapped so that the player can carry it on the shoulders.

The tuba is the largest, lowest-sounding orchestral brass instrument. It is a conical brass instrument, with a much mellower, distant sound than the trombone. Its bell (and the bell of the baritone and euphonium) may either point straight up or upward and forward.

In a Western orchestra or band, anything that is not classified as strings, woodwinds, or brass goes in the percussion section, including whistles. Most of the instruments in this section, though, are various drums and other instruments that are hit with drumsticks or beaters. Here are some of the more common instruments found in an orchestra percussion section.

Timpani are large kettledrums (drums with a rounded bottom) that can be tuned to play specific pitches. An orchestra or wind ensemble will usually have a few tympani of various sizes.

Other common drums do not have a particular pitch. They are usually cylindrical, sometimes with a drum head on each end of the cylinder. They include the small side drum, which often has a snare that can be engaged to give the drum an extra rattling sound, the medium-sized tenor drum, and the large bass drum. All orchestral drums (including tympani) are played using hard drum sticks or softer beaters. Drums that are played with the hands, like bongos, are rare in traditional orchestras and bands.

Cymbals can be clashed together, hit with a beater, or slapped together in "hi-hat" fashion. For smaller ensembles, various cymbals and drums may be grouped into a drum set so that one player can play all of them. Gongs are usually larger and thicker than cymbals and are usually hit with a soft beater.

There is only one group of common percussion instruments on which it is easy to play a melody. In these instruments, bars, blocks or tubes are arranged in two rows like the black and white keys of a piano keyboard. Orchestral xylophones and marimbas use wooden bars arranged over hollow tubes that help amplify their sound. The glockenspiel uses metal bars (like the familiar children's xylophone), and tubular bells use long, hollow, metal tubes.

Common percussion extras that add special color and effects to the music include the tambourine, triangle, maracas and other shakers, castanets, claves and various wood blocks, and various bells and scrapers.