alegres, valientes, osados,

cantemos, soldados, el himno á la lid,

y á nuestros acentos

el orbe se admire y en nosotros

mire los hijos del Cid,

y á nuestros acentos

el orbe se admire y en nosotros

mire los hijos del Cid.

Sol-etc.

247

248

249

250

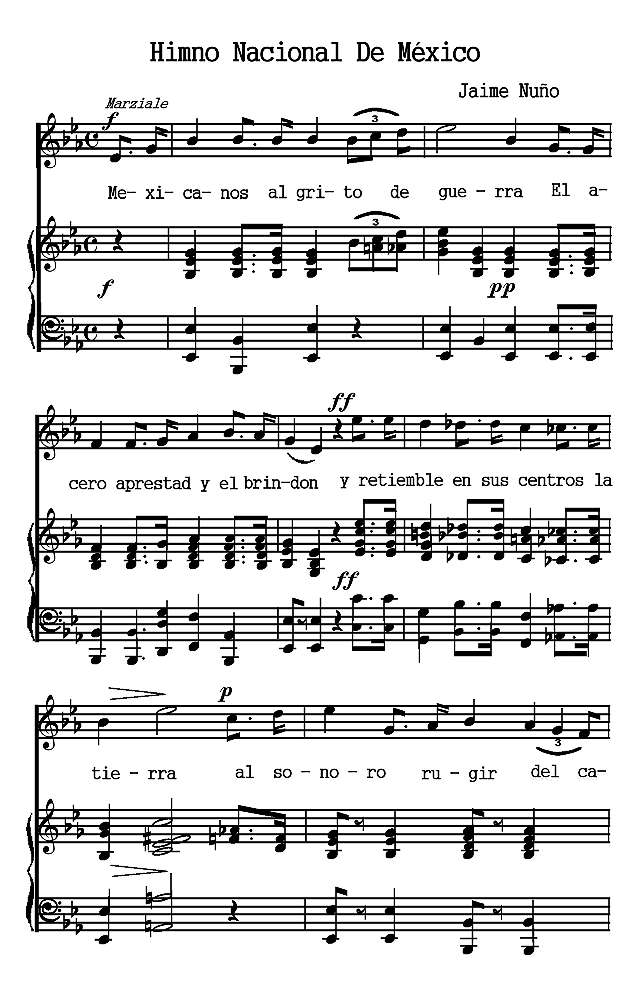

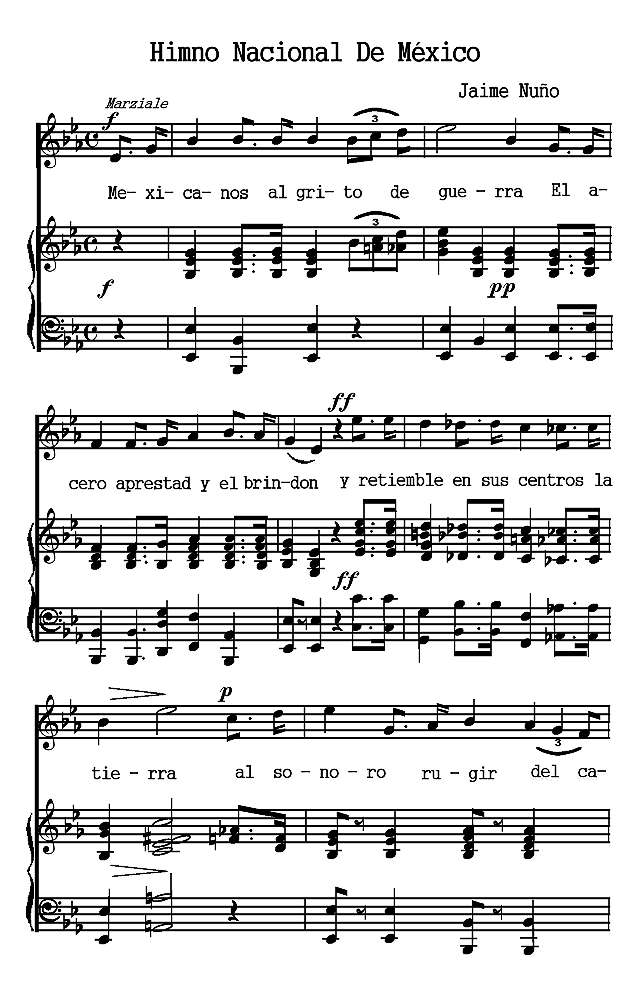

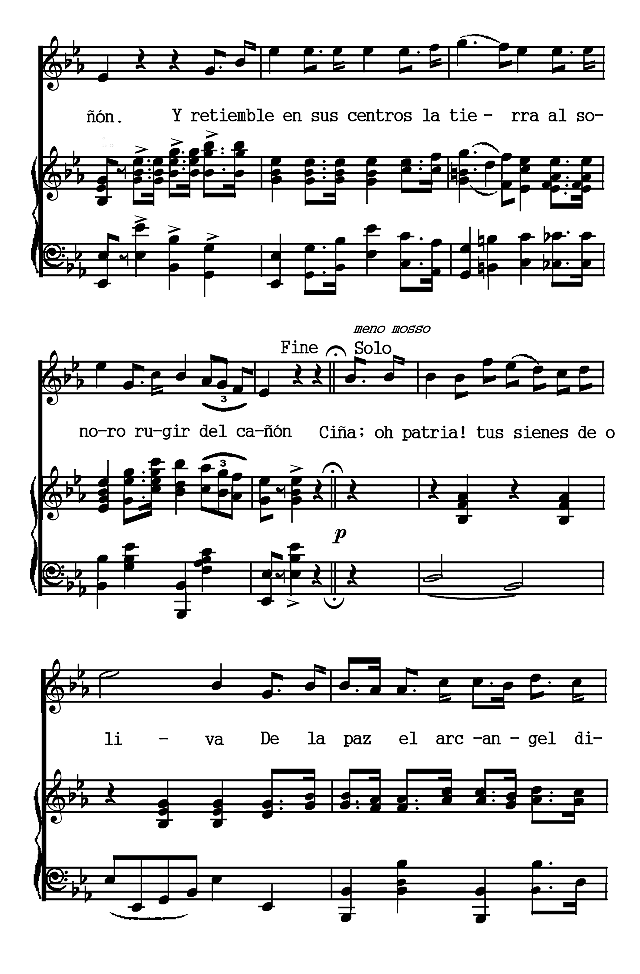

Mexicanos al grito de guerra

El acero aprestad y el bridón,

y retiemble en sus centros la tierra

al sonoro rugir del cañon.

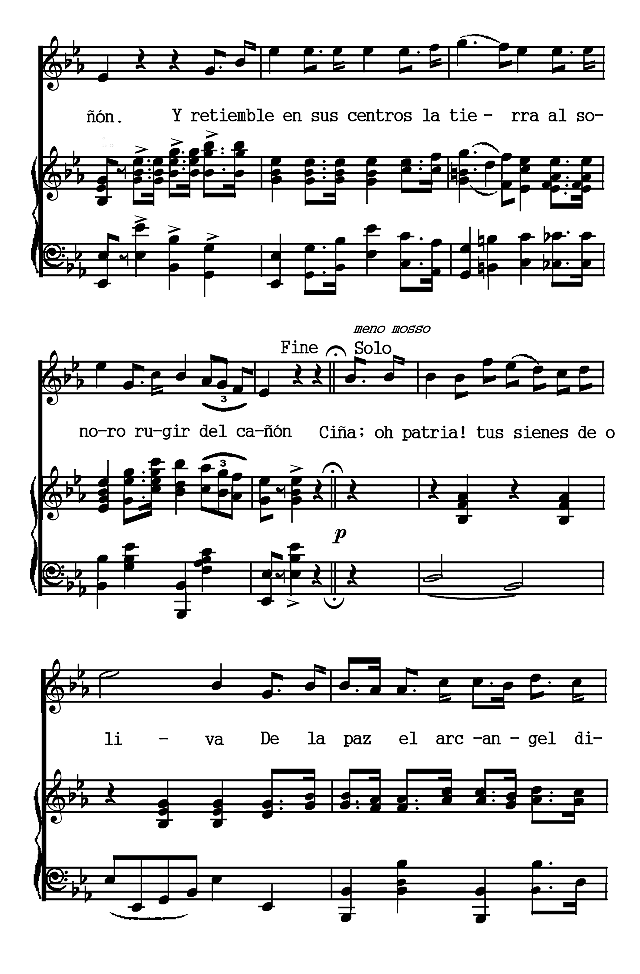

Y retiemble en sus centros la tierra

al sonoro rugir del cañón.

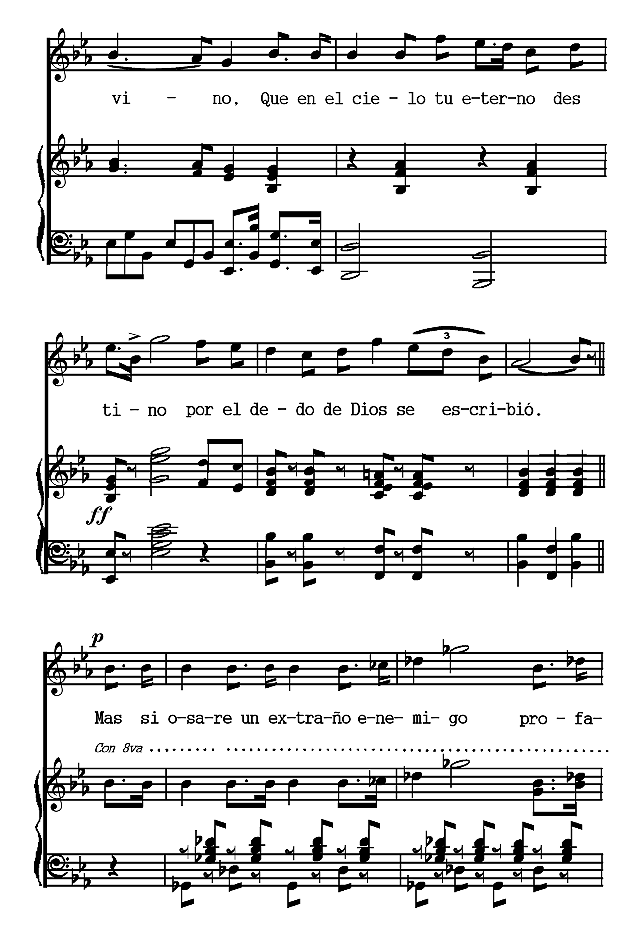

Ciña ¡oh patria! tus sienes de oliva

De la paz el arcángel divino,

Que en el ciélo tu eterno destino

por el dedo de Dios se escribió.

Mas si osare un extraño enemigo

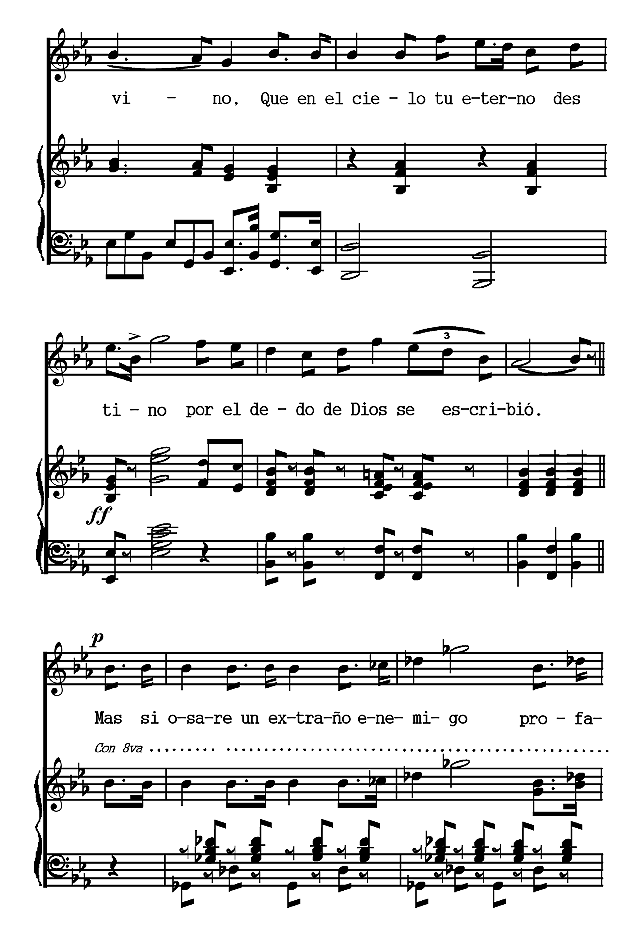

profanar con su planta tu suelo

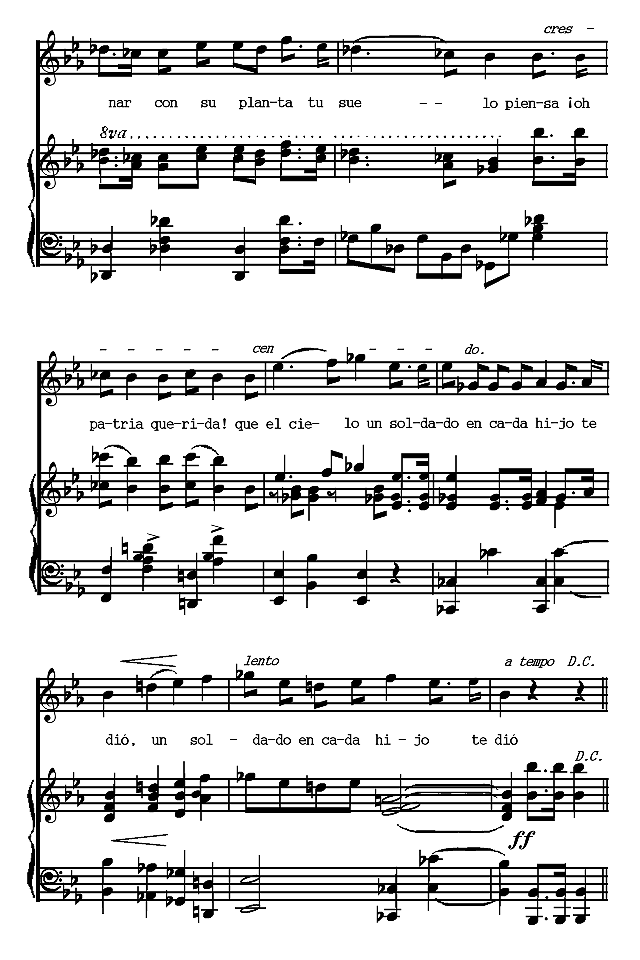

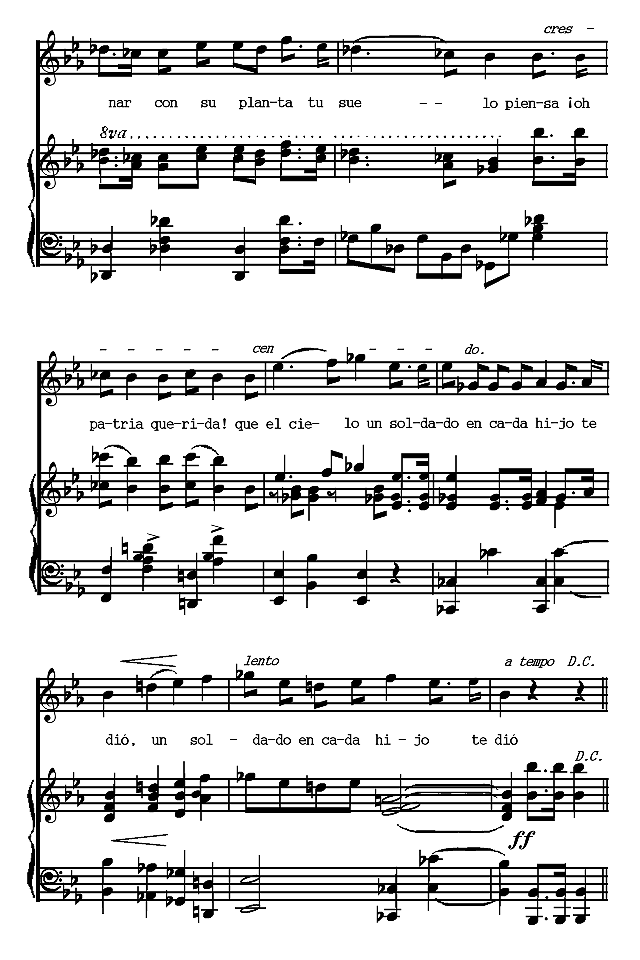

piensa ¡oh patria querida! que el cielo

un soldado en cada hijo te dió,

un soldado en cada hijo te dió.

251

252

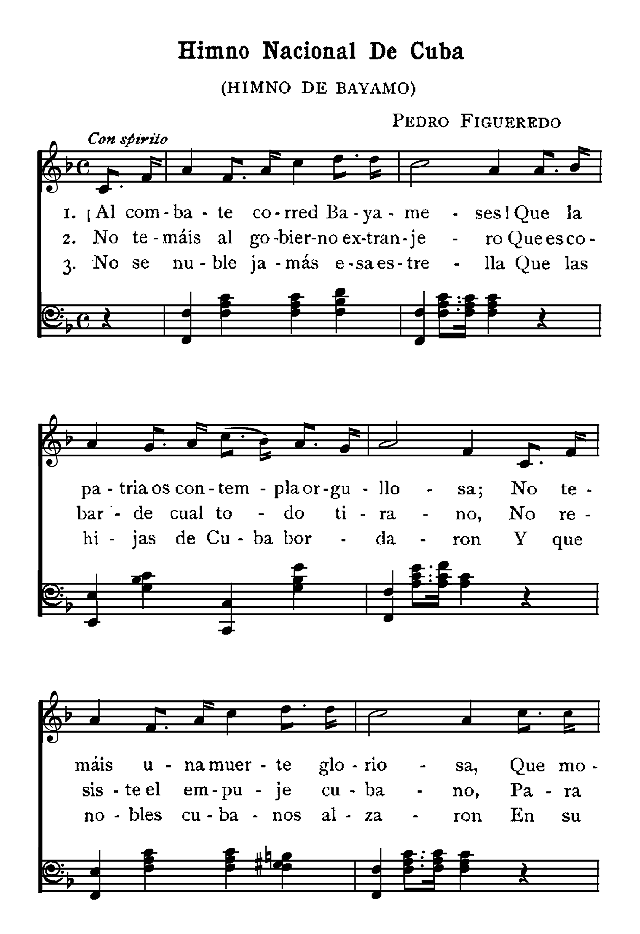

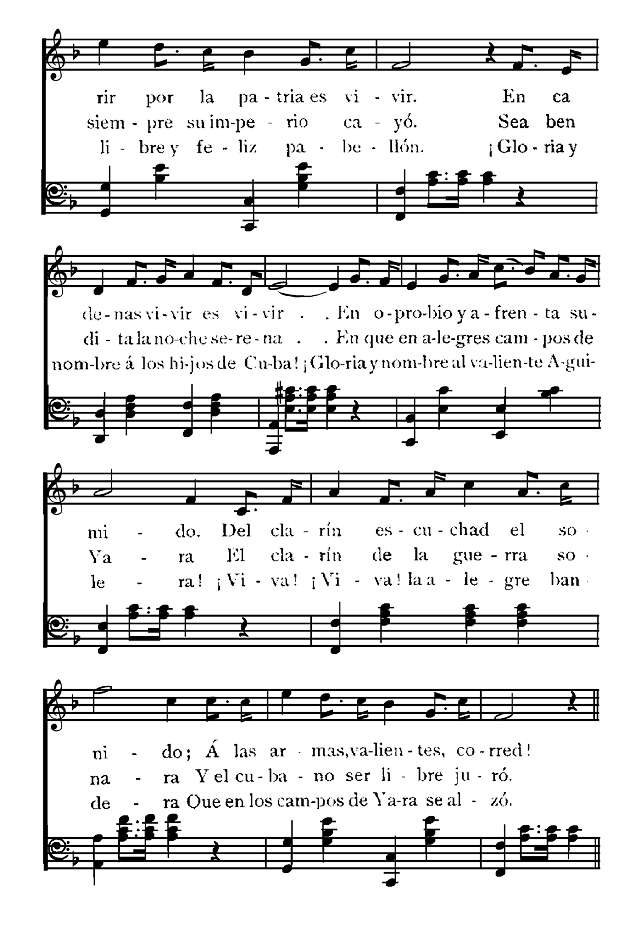

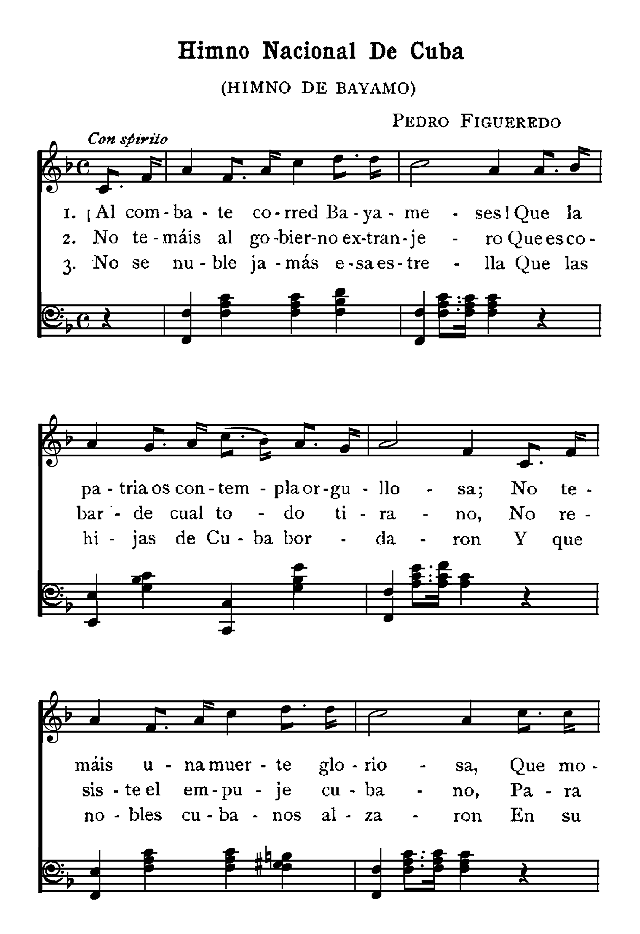

1. ¡Al combate corred Bayameses!

Que la patria os contempla orgullosa;

No temáis una muerte gloriosa,

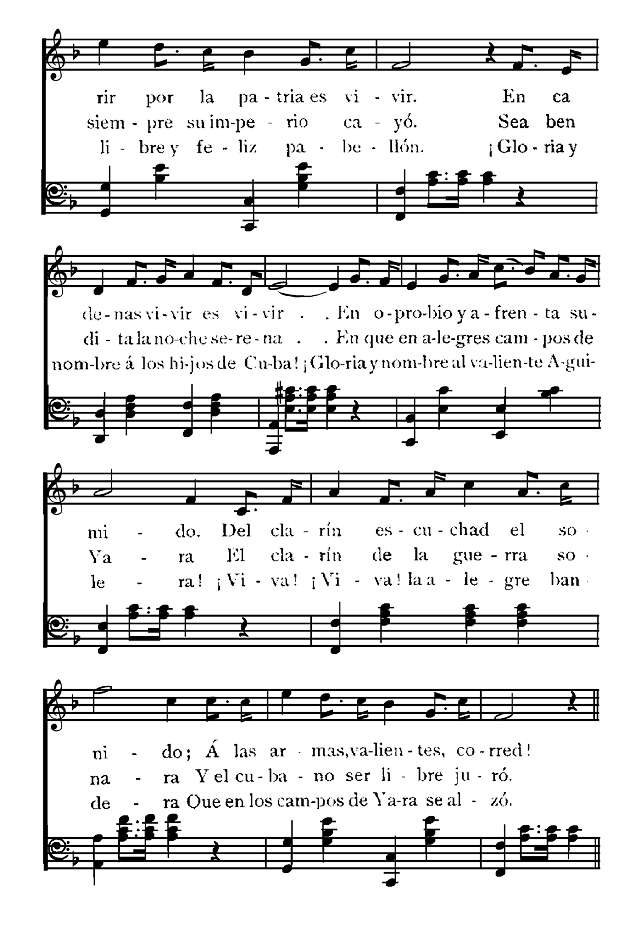

Que morir por la patria es vivir.

En cadenas vivir es vivir

En oprobio y afrenta sumido.

Del clarín escuchad el sonido;

Á las armas, valientes, corred!

2. No temáis al gobierno extranjero

Que es cobarde cual todo tirano,

No resiste el empuje cubano,

Para siempre su imperio cayó.

Sea bendita la noche serena

En que en alegres campos de Yara

El clarín de la guerra sonara

Y el cubano ser libre juró.

3. No se nuble jamás esa estrella

Que las hijas de Cuba bordaron

Y que nobles cubanos alzaron

En su libre y feliz pabellón.

¡Gloria y nombre á los hijos de Cuba!

¡Gloria y nombre al valiente Aguilera!

¡Viva! ¡Viva! la alegre bandera

Que en los campos de Yara se alzó.

253

NOTES

The heavy figures refer to pages of the text; the light figures to lines.

ROMANCES. The Spanish romances viejos, which correspondin form and spirit to the early English and Scotch ballads, exist ingreat number and variety. Anonymous and widely known amongthe people, they represent as well as any literary product can thespirit of the Spanish nation of the period, in the main stern andmartial, but sometimes tender and plaintive. Most of themwere written in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; the earliestto which a date can be assigned is Cercada tiene á Baeza, whichmust have been composed soon after 1368. Others may havetheir roots in older events, but have undergone constant modificationsince that time. The romance popular is still alive in Spainand many have recently been collected from oral tradition (cf.Menéndez y Pelayo, Antología, vol. X).

The romances were once thought to be relics of very old lyrico-epicsongs which, gathering material in the course of time, becamethe long epics that are known to have existed in Spain in thetwelfth to fourteenth centuries (such as the Poema del Cid, andthe lost cantares of Bernardo del Carpio, the Infantes de Lara and Fernán González). But modern investigation has shown conclusivelythat no such age can be ascribed to the romances in theirpresent form, and that in so far as they have any relation withthe epic cycles just cited they are rather descendants of themthan ancestors,—striking passages remembered by the peopleand handed down by them in constantly changing form. Manyare obviously later in origin; such are the romances fronterizos,springing from episodes of the Moorish wars, and the romancesnovelescos, which deal with romantic incidents of daily life. The romances juglarescos are longer poems, mostly concerned with 254Charlemagne and his peers, veritable degenerate epics, composedby itinerant minstrels to be sung in streets and taverns to throngsof apprentices and rustics. They have not the spontaneity andvigor which characterize the better romances viejos.

A few of the romances were printed in the Cancionero general of 1511, and more in loose sheets ( pliegos sueltos) not much laterin date; but the great collections which contain nearly all thebest we know were the Cancionero de romances "sin año," (shortly before 1550), the Cancionero de romances of 1550 andthe Silva de varios romances (3 parts, 1550). The most comprehensivemodern collection is that of A. Durán, Romancero general,2 vols., Madrid, 1849-1851 (vols. 10 and 16 of the Biblioteca deAutores españoles). The best selected is the Primavera y flor deromances of Wolf and Hofmann (Berlin, 1856), reprinted invols. VIII and IX of Menéndez y Pelayo's Antología de poetas líricoscastellanos. This contains nearly all the oldest and best romances,and includes poems from pliegos sueltos and the second part ofthe Silva, which were not known to Durán. Menéndez y Pelayo,in his Apéndices á la Primavera y flor (Antol. vol. IX) has givenstill more texts, notably from the third part of the Silva, one ofthe rarest books in the world. The fundamental critical works onthe romances are: F. Wolf, Ueber die Romanzenpoesie der Spanier(in Studien, Berlin, 1859); Milá y Fontanals, De la poesía heroico-popularcastellana (1874); and Menéndez y Pelayo, Tratado delos romances viejos (vols. XI and XII of the Antología, Madrid,1903-1906).

The romances, as usually printed, are in octosyllabic lines,with a fixed accent on the seventh syllable of each and assonancein alternate lines.

Many English translators have tried their hand at Spanishballads, as Thomas Rodd (1812), J. C.

Lockhart (1823), JohnBowring (1824), J.Y. Gibson (1887) and others. Lockhart'sversions are the best known and the least literal.

In the six romances included in this collection the lyrical quality 255predominates above the narrative (cf. the many rimes in- or in Fonte-frida and El prisionero). Abenámar is properly a frontierballad, and La constancia, perhaps, belongs with the Carolingiancycle; but the rest are detached poems of a romantic nature.(See S.G. Morley's Spanish Ballads, New York, 1911.)

1.—Abenámar is one of a very few romances which are supposedto have their origin in Moorish popular poetry. TheChristian king referred to is Juan II, who defeated the Moorsat La Higueruela, near Granada, in 1431. It is said that onthe morning of the battle he questioned one of his Moorishallies, Yusuf Ibn Alahmar, concerning the conspicuous objectsof Granada. The poem was utilized by Chateaubriand fortwo passages of Les aventures du dernier Abencérage.

1. Abenámar = Ibn Alahmar: see above.

9. The verbal forms in- ara and- iera were used then as nowas the equivalent of the pluperfect or the preterit indicative.

11. la: la verdad is probably understood. Cf. p. 2, l. I.

2.—1. diría = diré. In the romances the conditional oftenreplaces the future, usually to fit the assonance.

5. relucían: in the old ballads the imperfect indicative isoften used to express loosely past time or even present time.

6. El Alhambra: in the language of the old ballads el, not la, is used before a feminine noun with initial- a or e-, whetherthe accent be on the first syllable or not.

25. viuda in old Spanish was pronounced viuda and assonatedin í-a. This expletive que is common in Spanish: donot translate.

27. grande merely strengthens bien.

3.—Fonte-frida is a poem of erotic character, much admiredfor its suave melancholy. Probably it is merely anallegorical fragment of a longer poem now lost. It is one ofthose printed in the Cancionero general of 1511. It was welltranslated by Bowring. There is also a metrical version inTicknor, I, III. This theme is found in the Physiologus, a 256medieval bestiary. One of these animal stories relates thatthe turtle-dove has but one mate and if this mate dies thedove remains faithful to its memory. Cf. Mod. Lang. Notes,June, 1904 ( Turtel-Taube), and February, 1906.

3. In avecicas and tortolica the diminutive ending- ica seems to be quite equivalent to- ito. Cf.

Knapp's Span.Gram., 760a.

4. van tomar = van á tomar.

7. fuera: note that fué (or fuera) á pasar = pasó. This usageis now archaic, although it is still sometimes used by modernpoets: see p. 136, l. 18.

18. bebía: see note, p. 2, l. 5.

19. haber, in the ballads, often = tener. See also haya inthe following line.

4.—El Conde Arnaldos. Lockhart says of "Count Arnaldos,""I should be inclined to suppose that

'More is meant than meets the ear,'

—that some religious allegory is intended to be shadowedforth." Others have thought the same, and the strong mysticstrain in Spanish character may bear out the opinion. In orderthat the reader may judge for himself he should have beforehim the mysterious song itself, which, omitted in the earliestversion, is thus given in the Cancionero de romances of 1550,to follow line 18 of the poem:

—Galera, la mi galera,

Dios te me guarde de mal,

de los peligros del mundo

sobre aguas de la mar,

de los llanos de Almería,

del estrecho de Gibraltar,

y del golfo de Venecia,

y de los bancos de Flandes,

y del golfo de León,

donde suelen peligrar.

257

Popular poems which merely extol the power of music overanimals are not uncommon.

1. ¡Quién hubiese! would that one might have! or would thatI might have! Note ¡quién me diese! (p. 7, 1. 25), would thatsome one would give me!: this is the older meaning of quién inthese expressions. Note also ¡Quién supiera escribir! (p.134), would that I could write! where the modern usage occurs.

22. dígasme = dime This use of the pres. subj. with theforce of an imperative is not uncommon in older Spanish.

24. le fué á dar: see note, p. 3,1. 7.

5.—La constancia. These few lines, translated by Lockhartas "The Wandering Knight's Song,"

are only part of alost ballad which began:

Á las armas, Moriscote,

si las has en voluntad.

Six lines of it have recently been recovered (Menéndez yPelayo, Antología, IX, 211). It seems to have dealt with anincursion of the French into Spain, and the lines here givenare spoken by the hero Moriscote, when called upon to defendhis country. Don Quijote quotes the first two lines of thisballad, Part I, Cap. II.

8. de me dañar = de dañarme.

13. vos was formerly used in Spanish as usted is now used,—informal address.

El amante desdichado. Named by Lockhart "Valladolid."It is one of the few old romances which have kept alive inoral tradition till the present day, and are still repeated bythe Spanish peasantry (cf. Antología, X, 132, 192).

7.—El prisionero. Twelve lines of this poem were printedin 1511. It seems to be rather troubadouresque thanpopular in origin, but it became very well known later.Lockhart's version is called "The Captive Knight and theBlackbird."

258

16. This line is too short by one syllable, or has archaichiatus. See Versification,(4) a.

19. las mis manos: in old Spanish the article was oftenused before a possessive adjective that preceded its noun.This usage is now archaic or dialectic.

21. hacía is here exactly equivalent to hace in 1. 23: seenote, p. 2, 1. 5.

25. quien...me diese: see note, p. 4, 1. I.

8.—12. Oídolo había = lo había oído.

13. This line is too long by one syllable.

14. Gil Vicente (1470?-1540?), a Portuguese poet whowrote dramas in both Portuguese and Castilian. A strongcreative artist and thinker, Vicente is the greatest dramatistof Portugal and one of the great literary figures of the Peninsula.This Canción to the Madonna occurs in El auto de laSibila Casandra, a religious pastoral drama. Vicente himselfwrote music for the song, which was intended to accompanya dance. John Bowring made a very good metrical translationof the song ( Ancient Poetry and Romances of Spain, 1824,p. 315). Another may be found in Ticknor's History of SpanishLiterature, I, 259.

16. digas tú: see note, p. 4, I. 22. el marinero: omit el intranslation. In the Spanish of the ballads the article is regularly used with a noun in the vocative.

24. pastorcico: see note, p. 3, I. 3.

9. —Santa Teresa de Jesús (1515-1582), born at Ávila;became a Carmelite nun and devoted her life to reformingher Order and founding convents and monasteries. SaintTheresa believed herself inspired of God, and her devotionaland mystic writings have a tone of authority. Her chiefworks in prose are the Castillo interior and the Camino deperfección. She is one of the greatest of Spanish mystics, andher influence is still potent (cf. Juan Valera, Pepita Jiménez;Huysmans, En route; et al. ). Cf. Bibl. de Aut. Esp. , vols. 53 259and 55, for her works. This Letrilla has been translated byLongfellow ("Santa Teresa's Book-Mark," Riverside ed., 1886,VI., 216.)

9. —Fray Luis Ponce de León (1527-1591), born at Belmonte;educated at the University of Salamanca; became anAugustinian monk. While a professor at the same universityhe was accused by the Inquisition and imprisoned from 1572to 1576, while his trial proceeded. He was acquitted, and hetaught till his death, which occurred just after he had beenchosen Vicar-General of his Order. The greatest of the mysticpoets, he wrote as well religious works in prose ( Los nombresde Cristo, La perfecta casada), and in verse translated Virgil,Horace and other classical authors and parts of the OldTestament. In gentleness of character and in the purity inwhich he wrote his native tongue, he resembles the FrenchmanPascal. His poems are in vol. 37 of the Bibl.

de Aut. Esp. Cf. Ticknor, Period II, Cap. IX, and Introduction, p. xxii. La vida retirada is written in imitation of Horace's Beatus ille.

9. —17 to 10.—3. In these lines there is much poetic inversionof word-order. The logical order would be: Que ('for') el estadode los soberbios grandes no le enturbia el pecho, ni se admira del dorado techo, en jaspes sustentado, fabricado del sabio moro.

5. pregonera, as its gender indicates, modifies voz.

12.—10. In the sixteenth century great fortunes were madeby Spaniards who exploited the mines of their American coloniesacross the seas.

11. Note, this unusual enjambement; but the mente of adverbsstill has largely the force of a separate word.

Soneto: Á Cristo Crucificado. This famous sonnet hasbeen ascribed to Saint Theresa and to various other writers,but without sufficient proof. Cf. Fouché-Delbosc in RevueHispanique, II, 120-145; and ibid. , VI, 56-57. The poemwas translated by J.Y. Gibson ( The Cid Ballads, etc., 1887,II, 144), and there is also a version attributed to Dryden.

260

13.—Lope Félix de Vega Carpio (1562-1635) was the mostfertile playwright ever known to the world. Alone he createdthe Spanish drama almost out of nothing. Born at Madrid,where he spent most of his life, Lope was an infant prodigy whofulfilled the promise of his youth. His first play was writtenat the age of thirteen. He fought against the Portuguese inthe expedition of 1583 and took part in the disastrous Armadaof 1588. His life was marked by unending literary success,numerous love-affairs and occasional punishments therefor.In 1614 he was ordained priest. For the last twenty years ofhis life he was the acknowledged dictator of Spanish letters.

Lope's writings include some 2000 plays, of which perhaps500 are extant, epics, pastorals, parodies, short stories andminor poems beyond telling. He undertook to write in everygenre attempted by another and seldom scored a completefailure. His Obras completas are being published by theSpanish Academy (1890-); vol. 1 contains his life by Barrera.Most of his non-dramatic poems are in vol. 38 of the Bibl. deAut. Esp. ; others are in vols. 16 and 35. There is a Life inEnglish by H.A. Rennert (1904). Cf. also Introduction, p. xxiv.

Canción de la Virgen is a lullaby sung by the Madonnato her sleeping child in a palm grove.

The song occurs inLope's pastoral, Los pastores de Belén (1612). In Ticknor(II, 177), there is a metrical translation of the Canción.

The palm has great significance in the Roman CatholicChurch. On Palm Sunday,—the last Sunday of Lent,—branchesof the palm-tree are blessed and are carried in asolemn procession, in commemoration of the triumphal entryof Jesus into Jerusalem (cf. John, xii).

14. Ticknor translates these lines as follows:

Holy angels and blest,

Through these palms as you sweep,

Hold their branches at rest,

For my babe is asleep.

261

The literal meaning is: Since you are moving among the palms,holy angels, hold the branches, for my child sleeps. When thewind blows through the palm-trees their leaves rustle loudly.

14.—Mañana: translated by Longfellow (Riverside ed.,1886, VI, 204).

15. —Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Villegas (1580-1645),the greatest satirist in Spanish literature, was one of thevery few men of his time who dared criticize the powers thatwere. He was born in the province of Santander and was aprecocious student at Alcalá. His brilliant mind and hishonesty led him to Sicily and Naples, as a high official underthe viceroy, and to Venice and elsewhere on private missions;his plain-speaking tongue and ready sword procured him numerousenemies and therefore banishments. He was confinedin a dungeon from 1639 to 1643

at the instance ofOlivares, at whom some of his sharpest verses were directed.

Quevedo was a statesman and lover of his country driveninto pessimism by the ineptitude which he saw about him.He wrote hastily on many subjects and lavished a bitter,biting wit on all. His best-known works in prose are the picaresquenovel popularly called El gran tacaño (1626) and the Sueños (1627). His Obras completas are in course of publicationat Seville (1898-); his poems are in vol. 69 of the Bibl.de Aut. Esp. Cf. E. Mérimée, Essai sur la vie et les oeuvres deFrancisco de Quevedo (Paris, 1886), and Introduction, p. xxv.For a modern portrayal of one side of Quevedo's character,see Bréton de los Herreros, ¿ Quién es ella?

Epístola satírica: this epistle was addressed to Don Gasparde Guzmán, Conde-Duque de Olivares (d. 1645), the favoriteand prime minister of Philip IV. It is a remarkably boldprotest, for it was published in 1639 when Olivares was at theheight of his power. His disgrace did not occur till 1643.

8. Note the double meaning of sentir,—'to feel' and 'toregret.'

262

9. libre modifies ingenio. Translate: its freedom.

16. Que es lengua la verdad de Dios severo = que la verdades lengua de Dios severo.

16.—Letrilla Satírica was published in 1640.

.14 Genoa was then, as now, an important seaport andcommercial center. As the Spaniards bought many manufacturedarticles from Genoa, much of their money was"buried" there.

17. —Esteban Manuel de Villegas (d. 1669) was a lawyerwho wrote poetry only in his extreme youth. His Eróticas óAmatorias were published in 1617, and he says himself thatthey were written at fourteen and polished at twenty. Laterthe cares of life prevented him from increasing the poeticalfame that he gained thus early. He had a reputation forexcessive vanity, due partly to the picture of the rising sunwhich he placed upon the title-page of his poems with themotto Me surgente, quid istae? Istae referred to Lope, Quevedoand others. Villegas' poems may be found in vol. 42of the Bibl. de Aut. Esp. Cf. Menéndez y Pelayo, Hist. delos heterodoxos españoles, III, 859-875.

There is a parody of this well-known cantilena by Iglesiasin the Bibl. de Aut. Esp. , vol. 61, p.

477.

18. —Pedro Calderón de la Barca Henao de la Barreda yRiaño (1600-1681) was the greatest