- Set up the problem. That is, write the objective function and the constraints.

Since the simplex method is used for problems that consist of many variables, it is not practical to use the variables

x,

y,

z etc. We use the symbols

x1,

x2,

x3, and so on.

Let

x1=The number of hours per week Niki will work at Job I.

and

x2=The number of hours per week Niki will work at Job II.

It is customary to choose the variable that is to be maximized as

Z.

The problem is formulated the same way as we did in the Section 5.1.

Maximize

Z

=

40

x

1

+

30

x

2

Subject to:

x

1

+

x

2

≤

12

(7.1)2x1+x2≤16

(7.2)x1≥0 ; x2≥0

- Convert the inequalities into equations. This is done by adding one slack variable for each inequality.

For example to convert the inequality

x1+x2≤12 into an equation, we add a non-negative variable

y1, and we get

(7.3)x1+x2+y1=12

Here the variable

y1 picks up the slack, and it represents the amount by which

x1+x2 falls short of 12. In this problem, if Niki works fewer that 12 hours, say 10, then

y1 is 2. Later when we read off the final solution from the simplex table, the values of the slack variables will identify the unused amounts.

We can even rewrite the objective function

Z=40x1+30x2 as

–40x1–30x2+Z=0.

After adding the slack variables, our problem reads

Objective function:

–40x1–30x2+Z=0

Subject to constraints:

x1+x2+y1=12

(7.4)2x1+x2+y2=16

(7.5)x1≥0 ; x2≥0

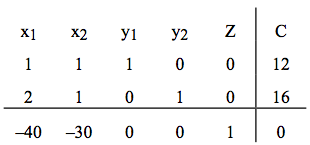

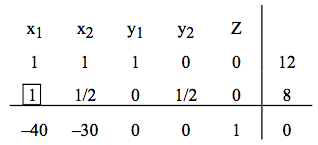

- Construct the initial simplex tableau. Write the objective function as the bottom row.

Now that the inequalities are converted into equations, we can represent the problem into an augmented matrix called the initial simplex tableau as follows.

Here the vertical line separates the left hand side of the equations from the right side. The horizontal line separates the constraints from the objective function. The right side of the equation is represented by the column

C.

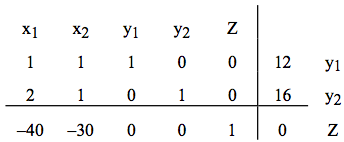

The reader needs to observe that the last four columns of this matrix look like the final matrix for the solution of a system of equations. If we arbitrarily choose

x1=0 and

x2=0, we get

Which reads

(7.7)y1=12

(7.8)y2=16

(7.9)Z=0

The solution obtained by arbitrarily assigning values to some variables and then solving for the remaining variables is called the basic solution associated with the tableau. So the above solution is the basic solution associated with the initial simplex tableau. We can label the basic solution variable in the right of the last column as shown in the table below.

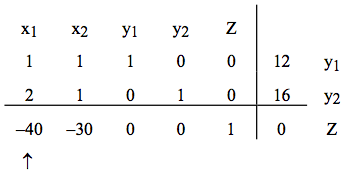

- The most negative entry in the bottom row identifies a column.

The most negative entry in the bottom row is –40, therefore the column 1 is identified.

Why do we choose the most negative entry in the bottom row?

The most negative entry in the bottom row represents the largest coefficient in the objective function – the coefficient whose entry will increase the value of the objective function the quickest.

The simplex method begins at a corner point where all the main variables, the variables that have symbols such as

x1,

x2,

x3 etc., are zero. It then moves from a corner point to the adjacent corner point always increasing the value of the objective function. In the case of the objective function

Z=40x1+30x2, it will make more sense to increase the value of

x1 rather than

x2. The variable

x1 represents the number of hours per week Niki works at Job I. Since Job I pays $40 per hour as opposed to Job II which pays only $30, the variable

x1 will increase the objective function by $40 for a unit of increase in the variable

x1.

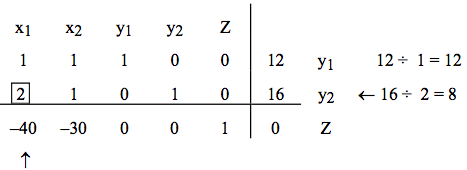

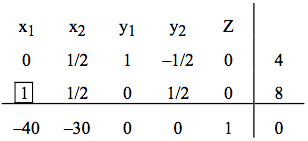

- Calculate the quotients. The smallest quotient identifies a row. The element in the intersection of the column identified in step 4 and the row identified in this step is identified as the pivot element.

As mentioned in the algorithm, in order to calculate the quotient, we divide the entries in the far right column by the entries in column 1, excluding the entry in the bottom row.

The smallest of the two quotients, 12 and 8, is 8. Therefore row 2 is identified. The intersection of column 1 and row 2 is the entry 2, which has been highlighted. This is our pivot element.

Why do we find quotients, and why does the smallest quotient identify a row?

When we choose the most negative entry in the bottom row, we are trying to increase the value of the objective function by bringing in the variable

x1. But we cannot choose any value for

x1. Can we let

x1=100? Definitely not! That is because Niki never wants to work for more than 12 hours at both jobs combined. In other words,

x1+x2≤12. Now can we let

x1=12? Again, the answer is no because the preparation time for Job I is two times the time spent on the job. Since Niki never wants to spend more than 16 hours for preparation, the maximum time she can work is

16÷2=8. Now you see the purpose of computing the quotients.

Why do we identify the pivot element?

As we have mentioned earlier, the simplex method begins with a corner point and then moves to the next corner point always improving the value of the objective function. The value of the objective function is improved by changing the number of units of the variables. We may add the number of units of one variable, while throwing away the units of another. Pivoting allows us to do just that.

The variable whose units are being added is called the entering variable, and the variable whose units are being replaced is called the departing variable. The entering variable in the above table is

x1, and it was identified by the most negative entry in the bottom row. The departing variable

y2 was identified by the lowest of all quotients.

- Perform pivoting to make all other entries in this column zero.

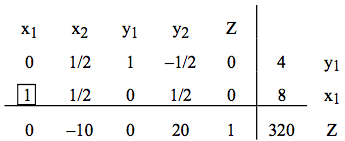

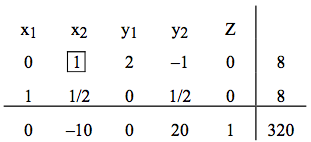

In Section 3.1, we used pivoting to obtain the row echelon form of an augmented matrix. Pivoting is a process of obtaining a 1 in the location of the pivot element, and then making all other entries zeros in that column. So now our job is to make our pivot element a 1 by dividing the entire second row by 2. The result follows.

To obtain a zero in the entry first above the pivot element, we multiply the second row by –1 and add it to row 1. We get

To obtain a zero in the element below the pivot, we multiply the second row by 40 and add it to the last row.

We now determine the basic solution associated with this tableau. By arbitrarily choosing

x2=0 and

y2=0, we obtain

x1=8,

y1=4, and

z=320. If we write the augmented matrix, whose left side is a matrix with columns that have one 1 and all other entries zeros, we get the following matrix stating the same thing.

We can restate the solution associated with this matrix as

x1=8,

x2=0,

y1=4,

y2=0 and

z=320. At this stage of the game, it reads that if Niki works 8 hours at Job I, and no hours at Job II, her profit

Z will be $320. Recall from Example 5.1 in the section called “Maximization Applications” that (8, 0) was one of our corner points. Here

y1=4 and

y2=0 mean that she will be left with 4 hours of working time and no preparation time.

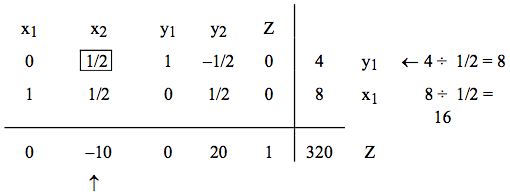

- When there are no more negative entries in the bottom row, we are finished; otherwise, we start again from step 4.

Since there is still a negative entry, –10 , in the bottom row, we need to begin, again, from step 4. This time we will not repeat the details of every step, instead, we will identify the column and row that give us the pivot element, and highlight the pivot element. The result is as follows.

We make the pivot element 1 by multiplying row 1 by 2, and we get

Now to make all other entries as zeros in this column, we first multiply row 1 by

−1/2